Document Resume Ed 366 050 Ea 025 505 Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2008 Agreement for the Recognition of The

November 30, 2007 Agreement for the Recognition of the Qalipu Mi’kmaq Band FNI DOCUMENT 2007 NOVEMBER 30, 1 November 30, 2007 Table of Contents Parties and Preamble...................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1 Definitions....................................................................................................... 4 Chapter 2 General Provisions ......................................................................................... 7 Chapter 3 Band Recognition and Registration .............................................................. 13 Chapter 4 Eligibility and Enrolment ............................................................................... 14 Chapter 5 Federal Programs......................................................................................... 21 Chapter 6 Governance Structure and Leadership Selection ......................................... 21 Chapter 7 Applicable Indian Act Provisions................................................................... 23 Chapter 8 Litigation Settlement, Release and Indemnity............................................... 24 Chapter 9 Ratification.................................................................................................... 25 Chapter 10 Implementation ........................................................................................... 28 Signatures ..................................................................................................................... 30 -

From Wimborne to Greenspond

Goulding/Goulden: From Wimborne to Greenspond Presentation by Bill Goulding to Wessex Society of Newfoundland January 12, 2011 Wimborne Minister Grand Falls - Windsor . Greenspond . .. Man Point Cove Gambo Reference: Wikipedia Commons (base map) DORSET Wimborne. Minister . Poole Reference: Wikipedia Commons (base map) 1809 letters from Newfoundland residents to John and William Fryer • Walter Ogden, Twillingate • James Randle, Twillingate • William Newberry, Fogo • Barnet Besstone, English Harbour, TB • John Wagg, Fogo • Daniel Sellars, Twillingate • William Etheridge, Fogo • Robert Ridout, Fogo • Joseph Oake, Fogo • William Wheeler, Bonavista • Joel Sanger, Greenspond • William Pardy, Burin • David Goulding, Greenspond • John Virge, Trinity • Richard and William Gale • William Manuel, Twillingate • Thomas Hix, Bonavista • John White, Twillingate • William Randall, Fogo • Mary Bath, Twillingate Greenspond N.F.Land June 17, 1809 Sir the Ann his Arrived the only vessel that Sailed from Poole in the Last fleet & No person hear have received a Letter or any freight from you this Spring But i have Diserd the people not to be to hasty untell thay hear further I Cannot tell how it his but i thought you would be the Last Man that would be Short in Letters but no person in Pond have heard from you this Spring But Be Provided your Dealors his Going to Draw their Money from you at a Short Notis witch i ham sorry for but if you Send Letters this Spring Lett me know what vessel his send them in & send me in the helene Now in Poole Beloing to Sleat -

August 2011 News Digest

News Digest™ August 2011 The Premier Organization for Municipal Clerks Since 1947 The City of Roses, Portland, OR, home to the Delegates and Guests of the 2012 IIMC Annual Conference IIMC STAFF DIRECTORY BOARD OF DIRECTORS News Digest™ ADMINISTRATION PRESIDENT Professionalism • Executive Director Colleen J. Nicol, MMC, Riverside, California In Local Government Chris Shalby [email protected] PRESIDENT ELECT Through Education [email protected] Brenda M. Cirtin, MMC, Springfield, Missouri Volume LXII No. 7 ISSN: 0145-2290 • Office Manager [email protected] Denice Cox AUGUST 2011 VICE PRESIDENT [email protected] Marc Lemoine, MMC, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Published 11 times each year the News Digest • Finance Specialist [email protected] is a publication of Janet Pantaleon IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT The International Institute of Municipal Clerks [email protected] Sharon K. Cassler, MMC, Cambridge, Ohio 8331 Utica Avenue, Suite 200 [email protected] Rancho Cucamonga, CA 91730 • Administrative Assistant Chris Shalby, Editor Maria E. Miranda DIRECTORS - 2012 EXPIRATION ([email protected]) [email protected] JAMES G. MULLEN, JR. CMC - I, Milton, Massachusetts Telephone: 909/944-4162 • (800/251-1639) [email protected] FAX: (909/944-8545) EDUCATION MELISSA (LISA) SMALL, MMC - III, Temple Terrace, Florida E-mail: [email protected] • Associate Director of Education [email protected] Jennifer Ward DEBORAH MINER, MMC - IV, Harrah, Oklahoma Founded in 1947, IIMC has more than 60 years of experience [email protected] [email protected] improving the professionalism of Municipal Clerks. IIMC TAMI K. KELLY, MMC - V, Grove City, Ohio has more than 10,000 members representing towns, small • MMC Verification Specialist [email protected] municipalities and large urban jurisdictions of more than Emily Maggard JULIE R. -

Improving Student Academic Achievement

TABLE OF CONTENTS Chairperson’s Message………………………………………………………2 District Overview.…………………………………………………………….3 Shared Commitments ……………………………………………………….7 Outcomes of Strategic Plan Goals and Objectives…………………...9 Highlights…………….……………………………………………………….27 Summary………………………………………………………………………30 Appendices……………………………………………………………………31 APPENDIX A: School Board Mandate APPENDIX B: Board of Trustees APPENDIX C: NCSD Enrollment by Grade and School, 2012-2013 APPENDIX D: Audited Statements NCSD Annual Report 2012-2013 CHAIRPERSON’S MESSAGE November 1, 2013 The Honourable Clyde Jackman Minister of Education Government of Newfoundland and Labrador P.O. Box 8700, Confederation Building St. John’s, NL A1B 4J6 Dear Minister Jackman: Effective September 1, 2013 the four English Language School Boards were consolidated into the Newfoundland and Labrador English School Board. The respective Chairpersons for the former boards were: Goronwy Price (Labrador), Don Brown (Western), John George (Nova Central) and Milton Peach (Eastern). The annual report for each school district was prepared in accordance with the Board’s requirements as a category one entity under the Transparency and Accountability Act, and was finalized after September 1, 2013. Therefore, it is my pleasure to present the Annual Report for 2012-2013 on behalf of the former Nova Central School Board. This report provides a balanced summary of the efforts and accomplishments of the Nova Central School Board in respect to the goals that are articulated in its strategic plan 2011- 2014, which addressed four areas: Student academic achievement, student retention, safe and caring schools and school leadership. The Nova Central School Board’s commitment to students and to learning is affirmed by the contents of the Annual Report. I want to thank our trustees and staff who have served the former school board and our students since 2005. -

GFW Community Profile Design Draft

Project Co‐ordinator: Gary Hennessey, Economic Development Officer Town of Grand Falls‐Windsor, NL Phone: 709‐489‐0483 / Fax: 709‐489‐0465 Email: [email protected] www.grandfallswindsor.com Project Facilitator: Kris Stone Research, Design & Layout By: Kris Stone Photos By: Kris Stone The Town of Grand Falls‐Windsor Grand Falls‐Windsor Heritage Society Up Sky Down Films Elmo Hewle MAYOR’S MESSAGE Welcome to the Grand Falls‐Windsor WCommunity Profile. This document has been created to showcase informaon on the many remarkable aspects that our community has to offer to current and potenal residents, as well as business owners. There are secons on demographics, aracons, events, tourism, community organizaons, the various types of businesses and industry in the area, as well as a lile bit of history on how our town got its start and became the municipality it is today. Grand Falls‐Windsor is the largest town in Central Newfoundland. The community is located along the banks of the Exploits River, seled within a serene valley atmosphere—a great place to live, work, and play. Its locaon also makes it a favourable place for doing business, as it is easily accessible from virtually all areas of the island. For this reason, Grand Falls‐Windsor has become known as a major service centre for Central Newfoundland and a hub for most of the island. Over the years our town connues to grow and prosper, with numerous housing developments steadily building family friendly neighbourhoods. There are many new and exisng businesses thriving and diversifying our economy in areas such as Aquaculture, Mining, Healthcare, Informaon Technology and Health Science Research, Post‐secondary Educaon, and Retail. -

RMHCNL Annual Report 2019

Weelo (Age 1) from St.Pierre et Miquleon. 1 stay, 501 nights. RONALD MCDONALD HOUSE CHARITIES® Newfoundland & Labrador Newfoundland & Labrador 2019 ANNUAL REPORT Natalia Williams (Age 6) Emma Clarke (Age 6) from Labrador City, NL. from Victoria, NL. 4 stays, 380 nights. 24 stays, 314 nights. Keeping families close TABLE OF CONTENTS VISION • MISSION • VALUES 4 Message from Board Chair & Executive Director 5 Board of Directors/Committees 6 FAMILY SUPPORT PROGRAMS 7 OUR IMPACT 2019 8 PULLING TOGETHER FOR FAMILIES 9 The Dedicated Volunteers 10 Strength in Numbers Volunteer Gathering 11 Helping Hand Awards 12 Adopt-a-Room Program 13 Community Events 14 McDonald’s: Our Founding and Forever Partner 15 Miss Achievement 16 OUR SIGNATURE EVENTS 17 Spare Some Love Bowling Event 18 “Fore” the Families Golf Classic 19 Red Shoe Crew – Walk for Families 20 Team RMHC 22 Sock It For Sick Kids & Their Families 23 Lights of Love Season of Giving Campaign 24 THANK YOU FROM OUR FAMILY TO YOURS 25 Donor Recognition 26 Seventh Birthday Celebration 28 MESSAGE FROM TREASURER 29 Financial Report 30 Vision Positively impact the health and lives of sick children, their families and their communities. Mission Ronald McDonald House Charities® Newfoundland and Labrador provides sick children and their families with a comfortable home where they can stay together in an atmosphere of caring, compassion and support close to the medical care and resources they need. Values Caring • Inclusion • Inspiration • Quality • Teamwork • Trust and Integrity MEET WEELO Generally, all mothers experiencing a high-risk pregnancy in Saint Pierre et Miquelon, a piece of French territory off the coast of Newfoundland, are referred to St. -

Review of Applications for Membership in the Qalipu Mi'kmaq First Nation Band Important Information for Applicants July 2013

IMPORTANT INFORMATION FOR APPLICANTS JULY 2013 REVIEW OF APPLICATIONS FOR MEMBERSHIP IN THE QALIPU MI’KMAQ FIRST NATION BAND Note: Applicants are advised that this document is not a substitute for the June 2013 Supplemental Agreement, the June 2013 Directive to the Enrolment Committee, or the 2008 Agreement. This Information Update is intended to provide general guidelines on what information applicants can start to gather to support their application for enrolment in the Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation. On July 4, 2013, Canada and the Federation of Newfoundland Indians (FNI) announced a Supplemental Agreement that clarifies the process for enrolment in the Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation and resolves issues that emerged in the implementation of the 2008 Agreement. All applications submitted between December 1, 2008, and November 30, 2012, except those previously rejected, will be reviewed to ensure that applicants meet the criteria for eligibility set out in the 2008 Agreement. This includes the applications of all those who have gained Indian status as members of the Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation. No new applications will be accepted. In November 2013, all applicants, except those Checklist previously rejected, will be sent a letter. Where an application is invalid, the letter will advise applicants that Ensure your address is up to date (Section A) their application is denied. Where an application is valid, Provide birth certificate, and proof of the letter will outline general documentation and request, by September 3, 2013 (Section B) informational requirements as well as where to send additional information applicants may wish to submit. It Understand Requirements to support is the sole responsibility of applicants to determine what self-identification (Section C) additional documentation they wish to submit in support Gather documents to support demonstration of their applications. -

Minutes Public Meeting Central Newfoundland

MINUTES PUBLIC MEETING CENTRAL NEWFOUNDLAND SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT June 17, 2003 at 7:00 p.m. Norris Arm Town Hall The attendance list is attached. Chairperson, Allan Scott, welcomed all those in attendance. He explained that the purpose of the meeting was to inform community representatives on the status of the Central Newfoundland Waste Management Study. He introduced Wayne Manuel from Bae Newplan. Mr. Manuel did a PowerPoint presentation on the overview of the study and progress report on Phase II. When Mr. Manuel was finished, there was an opportunity for questions and comments from the attendees. Questions: Q. Is the committee looking at the impact of tourism due to the location of the main facility? A. Not at this time. Q. Are you aware that the Town of Norris Arm North is on a ground water supply? A. No. Q. Do you know the leakage from a lined landfill? A. Theoretically they are designed not to leak. There are monitoring systems to control and treat leachate. -2- Q. Why don’t we start small with community recycling etc? A. Cannot meet guidelines as per government strategy (50% reduction) by voluntary involvement. Q. Will this impact the water supply in Norris Arm North? A. Studies will be conducted to determine any impacts on communities and their infrastructure. Q. Should the industrial sector be responsible for covering costs of handling construction and demolition? A. Any product that has a market value will be sold. Tipping fees will cover any handling costs. Q. When the site is chosen, who will police? Are we working with local or provincial regulations? A. -

Source Water Quality for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland And

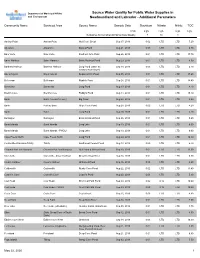

Department of Municipal Affairs Source Water Quality for Public Water Supplies in and Environment Newfoundland and Labrador - Additional Parameters Community Name Serviced Area Source Name Sample Date Strontium Nitrate Nitrite TOC Units mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality 7 10 1 Anchor Point Anchor Point Well Cove Brook Sep 17, 2019 0.02 LTD LTD 7.20 Aquaforte Aquaforte Davies Pond Aug 21, 2019 0.00 LTD LTD 6.30 Baie Verte Baie Verte Southern Arm Pond Sep 26, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 17.70 Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Pond Aug 29, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 9.50 Bartletts Harbour Bartletts Harbour Long Pond (same as Sep 18, 2019 0.03 LTD LTD 6.70 Castors River North) Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Sugarloaf Hill Pond Sep 05, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 17.60 Belleoram Belleoram Rabbits Pond Sep 24, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 14.40 Bonavista Bonavista Long Pond Aug 13, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 4.10 Brent's Cove Brent's Cove Paddy's Pond Aug 14, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 15.10 Burin Burin (+Lewin's Cove) Big Pond Aug 28, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 4.90 Burin Port au Bras Gripe Cove Pond Aug 28, 2019 0.02 LTD LTD 4.20 Burin Burin Long Pond Aug 28, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 4.10 Burlington Burlington Eastern Island Pond Sep 26, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 9.60 Burnt Islands Burnt Islands Long Lake Sep 10, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 6.00 Burnt Islands Burnt Islands - PWDU Long Lake Sep 10, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 6.00 Cape Freels North Cape Freels North Long Pond Aug 20, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 10.30 Centreville-Wareham-Trinity Trinity Southwest Feeder Pond Aug 13, 2019 0.00 LTD LTD 6.70 Channel-Port -

Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

CENTRE FOR NEWFOUNDLAND STUDIES TOTAL OF 10 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED (Without Author's Pennission) 1WO ISLAND DIALECTS OF BONAVISTA BAY, NEWFOUNDLAND by © Linda M. Harris A thesis submitted to the school of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Linguistics Memorial University of Newfoundland March 2006 St. John's Newfoundland and Labrador Library and Bibliotheque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de !'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-19365-5 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-19365-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a Ia Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par !'Internet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve Ia propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni Ia these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

19 Century Newfoundland Outport Merchants the Jersey Room, Burin

19th century Newfoundland outport merchants The Jersey Room, Burin, c. 1885, S.H. Parsons photo (GPA collection). submitted to Provincial Historic Commemorations Program Dept. Business, Tourism, Culture & Rural Development P.O. Box 8700 St. John's, NL A1E 1J3 submitted by Robert H. Cuff Historian/Writer Gerald Penney Associates Limited PO Box 428, St. John’s, NL A1C 5K4 10 November 2014 Executive Summary In their impact on Newfoundland and Labrador’s economic development, patterns of settlement, and community life, 19th century outport merchants made a significant historic contribution. Their secondary impact, on the Province’s political and cultural development, may be less obvious but was nonetheless vital. Each merchant had a demonstrable impact beyond his home community, in that each supplied nearby communities. Although a merchant’s commercial home sphere was typically in the headquarters bay or region, the majority of the outport merchants were also involved in both fishing and in supplying planters/ fishers in migratory or vessel-based fisheries elsewhere: the Labrador and French Shore fisheries; the seal hunt; and the western boat and Bank fisheries of the south coast. For the purposes of this review it was found helpful to draw a distinction between “resident outport merchants” who lived the full range of their adult lives in rural Newfoundland and the “merchant gentry” whose outport residency was an episode in their business and family life which was otherwise substantially spent in the Old Country or in St. John’s. The resident group may be more worthy of consideration for the Province’s commemoration program. Existing commemorations tend to favour the merchant gentry. -

Codes Used in the Newfoundland Commercial and Recreational Fisheries

Environment Canada Environnement Canada •• Fisheries Service des peches and Marine Service et des sciences de la mer 1 DFO ll ll i ~ ~~ll[lflll ~i~ 1 \11 1f1i! l1[1li eque 07003336 Codes Used in the Newfoundland Commercial and Recreational Fisheries by Don E. Waldron Data Record Series No. NEW/D-74-2 Resource Development Branch Newtoundland Region ) CODES USED IN THE NEWFOUNDLAND COMMERCIAL AND RECREATIONAL FISHERIES by D.E. Waldron Resource Development Branch Newfoundland Region Fisheries & Marine Service Department of the Environment St. John's, N'fld. February, 1974 GULF FlSHERIES LIBRARY FISHERIES & OCEANS gwt.IV HEOUE DES PECHES GOLFE' PECHES ET OCEANS ABSTRACT Data Processing is used by most agencies involved in monitoring the recreational and commercial fisheries of Newfoundland. There are three Branches of the Department of the Environment directly involved in Data Collection and Processing. The first two are the Inspection and the Conservation and Protection Branches (the collectors) and the Economics and Intelligence Branch (the processors)-is the third. To facilitate computer processing, an alpha-numeric coding system has been developed. There are many varieties of codes in use; however, only species, gear, ICNAF area codes, Economic and Intelligence Branch codes, and stream codes will be dealt with. Figures and Appendices are supplied to help describe these codes. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ........... .. ... .... ... ........... ................ ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv LIST .or FIGURES ....... .................................... v LIST OF TABLES ............................................ vi INTRODUCTION l Description of Data Coding .............. ~ .. .... ... 3 {A) Coding Varieties ••••••••••••••• 3 (I) Species Codes 3 ( II ) Gear Codes 3 (III) Area Codes 3 (i) ICNKF 4 (ii) Statistical Codes 7 (a) Statistical Areas 7 (b) Statistical Sections 7 (c) Community (Settlement) Codes 17 (iii) Comparison of ICNAF AND D.O.E.