Hutchins, Harold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Wimborne to Greenspond

Goulding/Goulden: From Wimborne to Greenspond Presentation by Bill Goulding to Wessex Society of Newfoundland January 12, 2011 Wimborne Minister Grand Falls - Windsor . Greenspond . .. Man Point Cove Gambo Reference: Wikipedia Commons (base map) DORSET Wimborne. Minister . Poole Reference: Wikipedia Commons (base map) 1809 letters from Newfoundland residents to John and William Fryer • Walter Ogden, Twillingate • James Randle, Twillingate • William Newberry, Fogo • Barnet Besstone, English Harbour, TB • John Wagg, Fogo • Daniel Sellars, Twillingate • William Etheridge, Fogo • Robert Ridout, Fogo • Joseph Oake, Fogo • William Wheeler, Bonavista • Joel Sanger, Greenspond • William Pardy, Burin • David Goulding, Greenspond • John Virge, Trinity • Richard and William Gale • William Manuel, Twillingate • Thomas Hix, Bonavista • John White, Twillingate • William Randall, Fogo • Mary Bath, Twillingate Greenspond N.F.Land June 17, 1809 Sir the Ann his Arrived the only vessel that Sailed from Poole in the Last fleet & No person hear have received a Letter or any freight from you this Spring But i have Diserd the people not to be to hasty untell thay hear further I Cannot tell how it his but i thought you would be the Last Man that would be Short in Letters but no person in Pond have heard from you this Spring But Be Provided your Dealors his Going to Draw their Money from you at a Short Notis witch i ham sorry for but if you Send Letters this Spring Lett me know what vessel his send them in & send me in the helene Now in Poole Beloing to Sleat -

August 2011 News Digest

News Digest™ August 2011 The Premier Organization for Municipal Clerks Since 1947 The City of Roses, Portland, OR, home to the Delegates and Guests of the 2012 IIMC Annual Conference IIMC STAFF DIRECTORY BOARD OF DIRECTORS News Digest™ ADMINISTRATION PRESIDENT Professionalism • Executive Director Colleen J. Nicol, MMC, Riverside, California In Local Government Chris Shalby [email protected] PRESIDENT ELECT Through Education [email protected] Brenda M. Cirtin, MMC, Springfield, Missouri Volume LXII No. 7 ISSN: 0145-2290 • Office Manager [email protected] Denice Cox AUGUST 2011 VICE PRESIDENT [email protected] Marc Lemoine, MMC, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Published 11 times each year the News Digest • Finance Specialist [email protected] is a publication of Janet Pantaleon IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT The International Institute of Municipal Clerks [email protected] Sharon K. Cassler, MMC, Cambridge, Ohio 8331 Utica Avenue, Suite 200 [email protected] Rancho Cucamonga, CA 91730 • Administrative Assistant Chris Shalby, Editor Maria E. Miranda DIRECTORS - 2012 EXPIRATION ([email protected]) [email protected] JAMES G. MULLEN, JR. CMC - I, Milton, Massachusetts Telephone: 909/944-4162 • (800/251-1639) [email protected] FAX: (909/944-8545) EDUCATION MELISSA (LISA) SMALL, MMC - III, Temple Terrace, Florida E-mail: [email protected] • Associate Director of Education [email protected] Jennifer Ward DEBORAH MINER, MMC - IV, Harrah, Oklahoma Founded in 1947, IIMC has more than 60 years of experience [email protected] [email protected] improving the professionalism of Municipal Clerks. IIMC TAMI K. KELLY, MMC - V, Grove City, Ohio has more than 10,000 members representing towns, small • MMC Verification Specialist [email protected] municipalities and large urban jurisdictions of more than Emily Maggard JULIE R. -

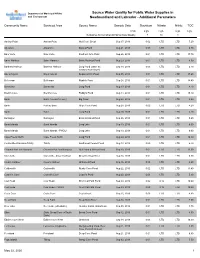

Source Water Quality for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland And

Department of Municipal Affairs Source Water Quality for Public Water Supplies in and Environment Newfoundland and Labrador - Additional Parameters Community Name Serviced Area Source Name Sample Date Strontium Nitrate Nitrite TOC Units mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality 7 10 1 Anchor Point Anchor Point Well Cove Brook Sep 17, 2019 0.02 LTD LTD 7.20 Aquaforte Aquaforte Davies Pond Aug 21, 2019 0.00 LTD LTD 6.30 Baie Verte Baie Verte Southern Arm Pond Sep 26, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 17.70 Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Pond Aug 29, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 9.50 Bartletts Harbour Bartletts Harbour Long Pond (same as Sep 18, 2019 0.03 LTD LTD 6.70 Castors River North) Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Sugarloaf Hill Pond Sep 05, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 17.60 Belleoram Belleoram Rabbits Pond Sep 24, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 14.40 Bonavista Bonavista Long Pond Aug 13, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 4.10 Brent's Cove Brent's Cove Paddy's Pond Aug 14, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 15.10 Burin Burin (+Lewin's Cove) Big Pond Aug 28, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 4.90 Burin Port au Bras Gripe Cove Pond Aug 28, 2019 0.02 LTD LTD 4.20 Burin Burin Long Pond Aug 28, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 4.10 Burlington Burlington Eastern Island Pond Sep 26, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 9.60 Burnt Islands Burnt Islands Long Lake Sep 10, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 6.00 Burnt Islands Burnt Islands - PWDU Long Lake Sep 10, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 6.00 Cape Freels North Cape Freels North Long Pond Aug 20, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 10.30 Centreville-Wareham-Trinity Trinity Southwest Feeder Pond Aug 13, 2019 0.00 LTD LTD 6.70 Channel-Port -

Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

CENTRE FOR NEWFOUNDLAND STUDIES TOTAL OF 10 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED (Without Author's Pennission) 1WO ISLAND DIALECTS OF BONAVISTA BAY, NEWFOUNDLAND by © Linda M. Harris A thesis submitted to the school of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Linguistics Memorial University of Newfoundland March 2006 St. John's Newfoundland and Labrador Library and Bibliotheque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de !'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-19365-5 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-19365-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a Ia Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par !'Internet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve Ia propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni Ia these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

19 Century Newfoundland Outport Merchants the Jersey Room, Burin

19th century Newfoundland outport merchants The Jersey Room, Burin, c. 1885, S.H. Parsons photo (GPA collection). submitted to Provincial Historic Commemorations Program Dept. Business, Tourism, Culture & Rural Development P.O. Box 8700 St. John's, NL A1E 1J3 submitted by Robert H. Cuff Historian/Writer Gerald Penney Associates Limited PO Box 428, St. John’s, NL A1C 5K4 10 November 2014 Executive Summary In their impact on Newfoundland and Labrador’s economic development, patterns of settlement, and community life, 19th century outport merchants made a significant historic contribution. Their secondary impact, on the Province’s political and cultural development, may be less obvious but was nonetheless vital. Each merchant had a demonstrable impact beyond his home community, in that each supplied nearby communities. Although a merchant’s commercial home sphere was typically in the headquarters bay or region, the majority of the outport merchants were also involved in both fishing and in supplying planters/ fishers in migratory or vessel-based fisheries elsewhere: the Labrador and French Shore fisheries; the seal hunt; and the western boat and Bank fisheries of the south coast. For the purposes of this review it was found helpful to draw a distinction between “resident outport merchants” who lived the full range of their adult lives in rural Newfoundland and the “merchant gentry” whose outport residency was an episode in their business and family life which was otherwise substantially spent in the Old Country or in St. John’s. The resident group may be more worthy of consideration for the Province’s commemoration program. Existing commemorations tend to favour the merchant gentry. -

Codes Used in the Newfoundland Commercial and Recreational Fisheries

Environment Canada Environnement Canada •• Fisheries Service des peches and Marine Service et des sciences de la mer 1 DFO ll ll i ~ ~~ll[lflll ~i~ 1 \11 1f1i! l1[1li eque 07003336 Codes Used in the Newfoundland Commercial and Recreational Fisheries by Don E. Waldron Data Record Series No. NEW/D-74-2 Resource Development Branch Newtoundland Region ) CODES USED IN THE NEWFOUNDLAND COMMERCIAL AND RECREATIONAL FISHERIES by D.E. Waldron Resource Development Branch Newfoundland Region Fisheries & Marine Service Department of the Environment St. John's, N'fld. February, 1974 GULF FlSHERIES LIBRARY FISHERIES & OCEANS gwt.IV HEOUE DES PECHES GOLFE' PECHES ET OCEANS ABSTRACT Data Processing is used by most agencies involved in monitoring the recreational and commercial fisheries of Newfoundland. There are three Branches of the Department of the Environment directly involved in Data Collection and Processing. The first two are the Inspection and the Conservation and Protection Branches (the collectors) and the Economics and Intelligence Branch (the processors)-is the third. To facilitate computer processing, an alpha-numeric coding system has been developed. There are many varieties of codes in use; however, only species, gear, ICNAF area codes, Economic and Intelligence Branch codes, and stream codes will be dealt with. Figures and Appendices are supplied to help describe these codes. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ........... .. ... .... ... ........... ................ ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv LIST .or FIGURES ....... .................................... v LIST OF TABLES ............................................ vi INTRODUCTION l Description of Data Coding .............. ~ .. .... ... 3 {A) Coding Varieties ••••••••••••••• 3 (I) Species Codes 3 ( II ) Gear Codes 3 (III) Area Codes 3 (i) ICNKF 4 (ii) Statistical Codes 7 (a) Statistical Areas 7 (b) Statistical Sections 7 (c) Community (Settlement) Codes 17 (iii) Comparison of ICNAF AND D.O.E. -

Making Connections Through Professional Partnering by Heather O'brien the Changeover from Library Student

• z The Atlantic Provinces Library Association Volume 66, Number 2 ISSN 0001-2203 No vember/December 2002 Making Connections Through Professional Partnering by Heather O'Brien The changeover from library student. I recently asked Heather school to the work world can to com me nt on th e program. seem daunting. New grad uates Here's what she had to say. may ask themselves how to plot HO : Ho w did th e idea for out th eir professional paths and "Professiona l Partnering" what to do (or not to do!) at th eir evolve ? first job interviews. Fortunately, a new program at th e S chool of HB: It actually evolved out of my Library and Information Studies participation in the Student-to (S LIS), Dalhousie University is CLA program this your and the seeking to facilitate this transi [CLA] confere nce in Halifax. I tion by pairing students with sp ent a great deal of time volun practicing professionals. The te er ing in the Job Link and Profess ional Partnering found that many students had Jamie Jarrett, Madeleine Lefebvre, Program was developed through significant concerns about mak Heather Berringer, Julia Stewart, ing the transition between th e S chool's CLA Student Melissa Schwartz a n d Mich ael school a nd their first "real job". Chapter and initiated by Colborne at a reception held recently Heather Berringer, a second-year to kickstart the partnering program. (continued on page 2) Inside This Issue APLA Executive 2002-2003 3 From Th e President's Desk 4 Basic Disaster Preparedness and Response Workshop 5 XHTML: The New Web Standard 6 Dalhousie Le arning Commons 7 The Nova Scotia Digital Collections Initiative 8 E-Parenting Webc ast 8 News From The Provinces 9 GAF : General Activities Fund 16 APLA Memorial Awards 17 Somers Scholarship 17 Win a Set of 200 3/2004 Hackmatack Nominated Books! 17 First Timer's Confere nce Grant '" 18 Margaret Williams Trust Fund Award 18 From St. -

Download (8MB)

Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1+1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de !'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votm refenmce ISBN: 978-0-494-55268-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-55268-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a Ia Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I' Internet, prater, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve Ia propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits meraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor Ia these ni des extraits substantials de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. without the author's permission. In compliance with the Canadian Conformement a Ia loi canadienne sur Ia Privacy Act some supporting forms protection de Ia vie privee, quelques may have been removed from this formulaires secondaires ont ete enleves de thesis. -

Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Foundation

TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents................................................................................................... 1 Chairperson’s Message.......................................................................................... 2 Mandate.................................................................................................................. 4 Overview................................................................................................................. 4 Vision........................................................................................................................ 5 Mission..................................................................................................................... 5 Goals......................................................................................................................... 6 Lines of Business..................................................................................................... 18 Designation, funding and plaquing programs for heritage structures Granting program for fishery related buildings Education Role/Sponsorship Role The Historic Places Initiative Program (HPI) Other Program Involvement.................................................................................. 21 Intangible Cultural Heritage Program (ICH) Ecclesiastical District of St. John’s Church Inventory Program/Church Forum Matchless Paint Collection Historic Colours of Newfoundland Heritage Day & Heritage Day Poster Contest Registered Heritage Structure -

CLPNNL By-Laws

COLLEGE BY-LAWS Table of Contents PART I: TITLE AND DEFINITIONS . 2 PART II: COLLEGE ADMINISTRATION . 3 PART III: COLLEGE BOARD AND STAFF. 5 PART IV: ELECTION(S). 8 PART V: MEETINGS . 11 PART VI: BOARD COMMITTEES . 14 PART VII: FEES/LICENSING. 15 PART VIII: GENERAL. 16 Appendix A: Electoral Zones. 17 Appendix B: Nomination Form . 29 1 PART I: TITLE AND DEFINITIONS By-laws Relating to the Activities of the College of Licensed Practical Nurses of Newfoundland and Labrador References in this document to the Act , Regulations and By-laws refer to the Licensed Practical Nurses Act (2005) ; the Licensed Practical Nurses Regulations (2011) and the By-laws incorporated herein, made under the Licensed Practical Nurses Act, 2005 . 1. Title These By-laws may be cited as the C ollege of Licensed Practical Nurses of Newfoundland and Labrador By-laws . 2. Defi nitions In these Bylaws , “act” means the Licensed Practical Nurses Act, 2005 ; “appointed Board member” means a member of the Board appointed under section 4 of the Act ; “Board” means the Board of the College of Licensed Practical Nurses of Newfoundland and Labrador as referred to in section 3 of the Act ; “Chairperson” means the chairperson of the Board elected under Section 3(8) of the Act ; “College” means the College of Licensed Practical Nurses of Newfoundland and Labrador as established by section 3 of the Act ; “elected Board member” means a member of the Board elected under section 3 of the Act ; “committee member” means a member of a committee appointed by the Board; “Registrar” means the Registrar of the College of Licensed Practical Nurses of Newfoundland and Labrador; “Licensee” means a member of the College who is licensed under section 12 of the Act ; “Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN)” means a practical nurse licensed under the Act ; and “Regulation” means a Regulation passed pursuant to the Act , as amended. -

Guide to Genealogical Material in the Newfoundland

GUIDE TO GENEALOGICAL MATERIAL IN THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR COLLECTION ST. JOHN’S PUBLIC LIBRARIES Compiled by David Leamon & Brenda Parmenter 2011 (8th Edition) Newfoundland and Labrador Collection St. John’s Public Libraries Provincial Resource Library Arts & Culture Centre (Third Floor) 95 Allandale Road St. John’s, NL Canada A1B 3A3 Web Site: http://www.nlpl.ca In this Guide, you will find that certain materials are designated available through interlibrary loan and others are not for loan. Requests for materials that are available through interlibrary loan must be made at your local public library. Materials that are not for loan may not be borrowed, but you may request information from these or any other materials in the Newfoundland and Labrador Collection. For further information: Telephone: 709-737-3955 Fax: 709-737-3958 E-mail: [email protected] —Cover design and document layout by John Griffin. INDEX HANDBOOKS, GUIDES, INDICES . 1 BIRTHS, MARRIAGES, DEATHS . 6 CHURCH RECORDS . 8 CEMETERY RECORDS . 9 CENSUS MATERIAL IN NOMINAL FORM . 10 DIRECTORIES OF RESIDENTS . 11 VOTERS’ LISTS . 13 DOCUMENTS OF THE POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT . 14 TELEPHONE DIRECTORIES . 15 WHO’S WHO . 18 FAMILY TREES & FAMILY HISTORIES . 21 COMMUNITY & FAMILY REUNIONS . 32 PLACE NAMES & STREET NAMES . 34 MIGRATION, SETTLEMENT, CULTURE . 36 COURT RECORDS . 39 PERIODICALS, JOURNALS, NEWSLETTERS . 40 COMMUNITY HISTORIES & MEMOIRS . 42 CHURCH HISTORIES . 59 MILITARY HISTORY . 68 SCHOOL YEARBOOKS . 72 STORIES OF THE SEA . 80 RAILWAY HISTORY . 85 YEARBOOKS, GAZETTEERS, MISCELLANEOUS DIRECTORIES . 86 MISCELLANEOUS MATERIAL . 87 LOCATION LEGEND CR = CONSERVATION ROOM NR = NEWFOUNDLAND ROOM PC = PROVINCIAL COLLECTION PR = PERIODICAL ROOM VT = VAULT - 1 - HANDBOOKS, GUIDES, INDICES (arranged alphabetically) Association of Newfoundland and Labrador Archives: Directory of ANLA Member Institutions 2003. -

THE GREENSPOND LETTER Volume 3, Number 1 January 1996

THE GREENSPOND LETTER Volume 3, Number 1 January 1996 Skating on Greenspond Harbour In This Issue PhotograplJ courtesy of tlJe Centre for A History of Greenspond Newfoundland Studies Archives, Memorial At Home With Elsie Phillipps University of Newfoundland Greenspond's Neighbours: Pinchard's Island Sealing List for the Year 1880 Correspondence of John Sainsbury Lots of Photos{ THE GREENSPOND LETTER 1 Table of Contents Letter from the Editor 2 History of Greenspond by Ralph Wright 4 18th Century Greenspond 13 Greenspond Neighbours: Pinchard's Island 14 Sealing List for 1880 16 Correspondence of John Sainsbury, 1903 and 1923 , 18 Names of Schooners that went to the Labrador Fishery , 20 At Home With Elsie Phillipps 21 The Greenspond Letter - a journal of the history of Greenspond through poetry, prose, photographs, and interviews. Greenspond is an island situated ·on the northwest side of Bonavista Bay. It was first settled over three centuries ago in the late 1690s, by people from the West Coqntry of England. Greenspond is one of the oldest continuously inhab ited outports in Newfoundland. In 1698 Greenspond was inhabited by 13 men, women and children. By 1810, the population was 600 and by 1901 the popula tion had risen to 1,726. Greenspond was one of the major settlements in New foundland. It was an important fishing, shipping and commercial centre and was called "The Capital of the North". The Greenspond Letter is published four times a year in January, April, July and October. Subscription rates are $20.00 per year. Please address all cor respondence to: Linda White 37 Liverpool Avenue St.