Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcasting Notice of Consultation CRTC 2012-212

Broadcasting Notice of Consultation CRTC 2012-212 PDF version Ottawa, 10 April 2012 Notice of hearing 7 June 2012 Gatineau, Quebec Deadline for submission of interventions/comments/answers: 10 May 2012 [Submit an intervention/comment/answer or view related documents] The Commission will hold a hearing commencing on 7 June 2012 at 2 p.m. at the Commission Headquarters, 1 Promenade du Portage, Gatineau, Quebec. The Commission intends to consider, subject to interventions, the following applications without the appearance of the parties: Applicant/licensee and locality 1. MOTV Média Inc. Across Canada Application 2012-0170-7 2. MOTV Média Inc. Across Canada Application 2012-0171-4 3. Rogers Broadcasting Limited Across Canada Application 2012-0173-0 4. 3924181 Canada Inc. Across Canada Application 2012-0197-0 5. Larry C. Osmond Grand Bank, Newfoundland and Labrador Application 2011-0969-5 6. Colba.Net Telecom Inc. Fredericton, Moncton, Saint John, Allardville, Big Cove, Blue Mountain Settlement, Bouctouche, Brown’s Flat, Burtts Corner, Cap Lumière, Davis Mill, Caron Brook, Centre-Acadie, Centre Napan, Clair, Harvey, Highway 505/St-Édouard, Jacquet River, Keating’s Corner, Lac Baker, Ludford Subdivision, McAdam, Morrisdale, Musquash Subdivision, Nasonworth, Noonan, Patterson/Hoyt, Petitcodiac, Richibucto, Ruchibucto Village, 2 Rogersville, St-André-de-Shediac, Ste-Anne-de-Kent, St-Antoine, St-Ignace, St-Joseph-de-Madawaska, Ste-Marie-de-Kent, Salmon Beach, Tracy/Fredericton Junction, Welsford, Willow Grove and their surrounding areas in New Brunswick; St. John’s, Deer Lake, Pasadena and their surrounding areas in Newfoundland and Labrador; Dartmouth, Halifax, Bedford, Sackville and their surrounding areas in Nova Scotia Application 2012-0174-8 7. -

From Wimborne to Greenspond

Goulding/Goulden: From Wimborne to Greenspond Presentation by Bill Goulding to Wessex Society of Newfoundland January 12, 2011 Wimborne Minister Grand Falls - Windsor . Greenspond . .. Man Point Cove Gambo Reference: Wikipedia Commons (base map) DORSET Wimborne. Minister . Poole Reference: Wikipedia Commons (base map) 1809 letters from Newfoundland residents to John and William Fryer • Walter Ogden, Twillingate • James Randle, Twillingate • William Newberry, Fogo • Barnet Besstone, English Harbour, TB • John Wagg, Fogo • Daniel Sellars, Twillingate • William Etheridge, Fogo • Robert Ridout, Fogo • Joseph Oake, Fogo • William Wheeler, Bonavista • Joel Sanger, Greenspond • William Pardy, Burin • David Goulding, Greenspond • John Virge, Trinity • Richard and William Gale • William Manuel, Twillingate • Thomas Hix, Bonavista • John White, Twillingate • William Randall, Fogo • Mary Bath, Twillingate Greenspond N.F.Land June 17, 1809 Sir the Ann his Arrived the only vessel that Sailed from Poole in the Last fleet & No person hear have received a Letter or any freight from you this Spring But i have Diserd the people not to be to hasty untell thay hear further I Cannot tell how it his but i thought you would be the Last Man that would be Short in Letters but no person in Pond have heard from you this Spring But Be Provided your Dealors his Going to Draw their Money from you at a Short Notis witch i ham sorry for but if you Send Letters this Spring Lett me know what vessel his send them in & send me in the helene Now in Poole Beloing to Sleat -

August 2011 News Digest

News Digest™ August 2011 The Premier Organization for Municipal Clerks Since 1947 The City of Roses, Portland, OR, home to the Delegates and Guests of the 2012 IIMC Annual Conference IIMC STAFF DIRECTORY BOARD OF DIRECTORS News Digest™ ADMINISTRATION PRESIDENT Professionalism • Executive Director Colleen J. Nicol, MMC, Riverside, California In Local Government Chris Shalby [email protected] PRESIDENT ELECT Through Education [email protected] Brenda M. Cirtin, MMC, Springfield, Missouri Volume LXII No. 7 ISSN: 0145-2290 • Office Manager [email protected] Denice Cox AUGUST 2011 VICE PRESIDENT [email protected] Marc Lemoine, MMC, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Published 11 times each year the News Digest • Finance Specialist [email protected] is a publication of Janet Pantaleon IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT The International Institute of Municipal Clerks [email protected] Sharon K. Cassler, MMC, Cambridge, Ohio 8331 Utica Avenue, Suite 200 [email protected] Rancho Cucamonga, CA 91730 • Administrative Assistant Chris Shalby, Editor Maria E. Miranda DIRECTORS - 2012 EXPIRATION ([email protected]) [email protected] JAMES G. MULLEN, JR. CMC - I, Milton, Massachusetts Telephone: 909/944-4162 • (800/251-1639) [email protected] FAX: (909/944-8545) EDUCATION MELISSA (LISA) SMALL, MMC - III, Temple Terrace, Florida E-mail: [email protected] • Associate Director of Education [email protected] Jennifer Ward DEBORAH MINER, MMC - IV, Harrah, Oklahoma Founded in 1947, IIMC has more than 60 years of experience [email protected] [email protected] improving the professionalism of Municipal Clerks. IIMC TAMI K. KELLY, MMC - V, Grove City, Ohio has more than 10,000 members representing towns, small • MMC Verification Specialist [email protected] municipalities and large urban jurisdictions of more than Emily Maggard JULIE R. -

The Hitch-Hiker Is Intended to Provide Information Which Beginning Adult Readers Can Read and Understand

CONTENTS: Foreword Acknowledgements Chapter 1: The Southwestern Corner Chapter 2: The Great Northern Peninsula Chapter 3: Labrador Chapter 4: Deer Lake to Bishop's Falls Chapter 5: Botwood to Twillingate Chapter 6: Glenwood to Gambo Chapter 7: Glovertown to Bonavista Chapter 8: The South Coast Chapter 9: Goobies to Cape St. Mary's to Whitbourne Chapter 10: Trinity-Conception Chapter 11: St. John's and the Eastern Avalon FOREWORD This book was written to give students a closer look at Newfoundland and Labrador. Learning about our own part of the earth can help us get a better understanding of the world at large. Much of the information now available about our province is aimed at young readers and people with at least a high school education. The Hitch-Hiker is intended to provide information which beginning adult readers can read and understand. This work has a special feature we hope readers will appreciate and enjoy. Many of the places written about in this book are seen through the eyes of an adult learner and other fictional characters. These characters were created to help add a touch of reality to the printed page. We hope the characters and the things they learn and talk about also give the reader a better understanding of our province. Above all, we hope this book challenges your curiosity and encourages you to search for more information about our land. Don McDonald Director of Programs and Services Newfoundland and Labrador Literacy Development Council ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the many people who so kindly and eagerly helped me during the production of this book. -

Documentation of Recent Grand Banks Iceberg Grounding Events and a Comparison with Older Events of Known

Environmental Studies Research Funds 157 Documentation of Recent Iceberg Grounding Evens and a Comparison with Older Events of Know Age, Northern Grand Bank, Canada April 2006 Environmental Studies Research Funds Report ESRF # 157 June, 2005 DOCUMENTATION OF RECENT GRAND BANK ICEBERG GROUNDING EVENTS AND COMPARISON WITH OLDER EVENTS OF KNOWN AGE 1 1 2 3 Gary SonnichsenP ,P Thian HundertP ,P Robert Myers P ,P Patricia PocklingtonP P 1 P P Geological Survey of Canada (Atlantic), P.O. Box 1006, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia B2Y 4A2 [email protected] UTH 2 P P Rob Myers Consulting, 17 Harbour Drive, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, B2Y 3N83 3 P P Arenicola Marine, Consultants in Marine Biology, 7 Bishop Ave., Wolfville N.S., B4P 2L3 The correct citation for this report is: Sonnichsen, G.V., Hundert, T., Pocklton, P. and Myers, R., 2005 Documentation of recent iceberg grounding events and a comparison with older events of known age, Northern Grand Bank, Canada, Environmental Studies Research Funds Report No.157, Calgary, 206 pp. The Environmental Studies Research Funds are financed from special levies on the oil and gas industry and administered by the National Energy Board for the Minister of Natural Resources Canada and the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. The Environmental Studies Research Funds and any person acting on their behalf assume no liability arising from the use of the information contained in this document. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Environmental Studies Research Funds agencies. The use of trade names or identification of specific products does not constitute an endorsement or recommendation for use. -

Cursillo Parish Contacts

Anglican Diocese of Central Newfoundland Cursillo Parish Contacts Mailing Name Phone # Email Address Parish Address General Delivery Minnie Janes 536-3247 Badger’s Quay Badger’s Quay, NL A0G 1B0 POBox 942 545-2105 Edith Bagg [email protected] Bonavista Bonavista, NL A0C 1B0 470-0431 General Delivery Wilson & Stella Mills 656-4481 [email protected] Gander Bay Boyd’s Cove, NL A0G 1G0 POBox 59 Geraldine Purchase 672-3503 Buchans Buchans, NL A0H 1G0 POBox 45 June Holloway [email protected] Smith's Sound Port Blandford, NL A0C2G0 POBox 310 Rev. Terry Caines 891-1377 Burin Burin, NL A0G1E0 24 Park Avenue Elsie Sullivan 466-2002 [email protected] Clarenville Clarenville, NL A5A 1V8 POBox 111 Garry & Dallas Mitchell 884-5319 Twillingate Durrell, NL A0G1Y0 POBox 85 Gordon & Thelma Davidge 888-3336 [email protected] Belleoram English Harbour W, NL A0H 1M0 General Delivery Judy Mahoney Fogo Island Fogo, NL A0G 2B0 POBox 398 Jean Rose 832-2297 Fortune/Lamaline Fortune, NL A0E 1P0 POBox 391 Jean Eastman 674-5213 [email protected] Gambo Gambo, NL A0G 1T0 113 Ogilvie Street John & Beryl Barnes 256-8184 Gander Gander, NL A1V 2R2 POBox 24 Herbert & Beulah Ralph 533-2567 Glovertown Glovertown South, NL A0G 2M0 POBox 571 Winston & Shirley Walters 832-1930 [email protected] Grand Bank Grand Bank, NL A0E 1W0 20 Dunn Place Robert & Thelma Stockley 489-6945 [email protected] Grand Falls GrandFalls-Windsor, NL A2A2M3 8 Dorrity Place Ed & Glenda Warford 489-6747 [email protected] Windsor GrandFalls-Windsor, -

Immigration Portal

Immigration Portal Main Page This section of our website has been constructed to help you, the visitor to this link, to get a better idea of the lifestyle and services that Channel-Port aux Basques offers you and your families as immigrants to our community. Please log on to the various links and hopefully, you'll find the answers to your questions about Channel-Port aux Basques. In the event that you need additional information, don't hesitate to contact the Economic Development Strategist for the town at any of the following means: E-mail:[email protected] Telephone: (709) 695-2214 Fax: (709) 695-9852 Regular mail: Town of Channel-Port aux Basques 67 Main Street P.O. Box 70 Channel-Port aux Basques, NL A0M 1C0 History Channel-Port aux Basques, the Gateway to Newfoundland, has been welcoming visitors for 500 years, from Basque Fisherman in the 1500's who found the ice free harbour a safe haven, to ferry passengers who commenced arriving on the "Bruce" steamship in 1898 to take the railway across the island. The area was actually settled on a year-round basis until fisher-folk from the Channel Islands established Channel in the early 1700's, although people had been working the south coast fishery year-round for a century before this. The name Port aux Basques came into common usage from 1764 onwards following surveys of Newfoundland and undertaken by Captain James Cook on behalf of the British Admiralty. Captain Cook went on to fame, if not fortune, as a result of his surveys in the Pacific Ocean, but it was he who surveyed the St. -

Garnish Burin – Marystown

Burin Peninsula Voluntary Clusters Project Directory of Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations Areas including: Placentia West Fortune Bay East Grand Bank - Fortune Frenchman’s Cove - Garnish Burin – Marystown Online Version Directory of Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations on the Burin Peninsula Community Sector Council Newfoundland and Labrador The Community Sector Council Newfoundland and Labrador (CSC) is a leader in the voluntary community sector in Canada. Its mission is to promote the integration of social and economic development, encourage citizen engagement and provide leadership in shaping public policies. Our services include conducting research to help articulate the needs of the voluntary community sector and delivery of training to strengthen organizations and build the skills of staff and volunteers. Acknowledgements Prepared with the assistance of Trina Appleby, Emelia Bartellas, Fran Locke, Jodi McCormack, Amelia White, and Louise Woodfine. Many thanks to the members of the Burin Peninsula Clusters Pilot Advisory Committee for their support: Kimberley Armstrong, Gord Brockerville, Albert Dober, Everett Farwell, Con Fitzpatrick, Mike Graham, Elroy Grandy, Charles Hollett, Ruby Hoskins, Kevin Lundrigan, Joanne Mallay-Jones, Russ Murphy, and Sharon Snook. Disclaimer The listing of a particular service or organization should not be taken to mean an endorsement of that group or its programs. Similarly, omissions and inclusions do not necessarily reflect editorial policy. Also, while many groups indicated they have no problem being included in a version of the directory, some have requested to be omitted from an online version. Copyright © 2011 Community Sector Council Newfoundland and Labrador. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole, or in part, is forbidden without written permission. -

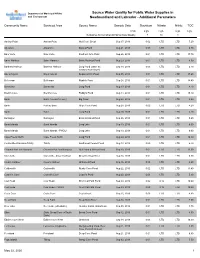

Source Water Quality for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland And

Department of Municipal Affairs Source Water Quality for Public Water Supplies in and Environment Newfoundland and Labrador - Additional Parameters Community Name Serviced Area Source Name Sample Date Strontium Nitrate Nitrite TOC Units mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality 7 10 1 Anchor Point Anchor Point Well Cove Brook Sep 17, 2019 0.02 LTD LTD 7.20 Aquaforte Aquaforte Davies Pond Aug 21, 2019 0.00 LTD LTD 6.30 Baie Verte Baie Verte Southern Arm Pond Sep 26, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 17.70 Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Pond Aug 29, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 9.50 Bartletts Harbour Bartletts Harbour Long Pond (same as Sep 18, 2019 0.03 LTD LTD 6.70 Castors River North) Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Sugarloaf Hill Pond Sep 05, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 17.60 Belleoram Belleoram Rabbits Pond Sep 24, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 14.40 Bonavista Bonavista Long Pond Aug 13, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 4.10 Brent's Cove Brent's Cove Paddy's Pond Aug 14, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 15.10 Burin Burin (+Lewin's Cove) Big Pond Aug 28, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 4.90 Burin Port au Bras Gripe Cove Pond Aug 28, 2019 0.02 LTD LTD 4.20 Burin Burin Long Pond Aug 28, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 4.10 Burlington Burlington Eastern Island Pond Sep 26, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 9.60 Burnt Islands Burnt Islands Long Lake Sep 10, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 6.00 Burnt Islands Burnt Islands - PWDU Long Lake Sep 10, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 6.00 Cape Freels North Cape Freels North Long Pond Aug 20, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 10.30 Centreville-Wareham-Trinity Trinity Southwest Feeder Pond Aug 13, 2019 0.00 LTD LTD 6.70 Channel-Port -

19 Century Newfoundland Outport Merchants the Jersey Room, Burin

19th century Newfoundland outport merchants The Jersey Room, Burin, c. 1885, S.H. Parsons photo (GPA collection). submitted to Provincial Historic Commemorations Program Dept. Business, Tourism, Culture & Rural Development P.O. Box 8700 St. John's, NL A1E 1J3 submitted by Robert H. Cuff Historian/Writer Gerald Penney Associates Limited PO Box 428, St. John’s, NL A1C 5K4 10 November 2014 Executive Summary In their impact on Newfoundland and Labrador’s economic development, patterns of settlement, and community life, 19th century outport merchants made a significant historic contribution. Their secondary impact, on the Province’s political and cultural development, may be less obvious but was nonetheless vital. Each merchant had a demonstrable impact beyond his home community, in that each supplied nearby communities. Although a merchant’s commercial home sphere was typically in the headquarters bay or region, the majority of the outport merchants were also involved in both fishing and in supplying planters/ fishers in migratory or vessel-based fisheries elsewhere: the Labrador and French Shore fisheries; the seal hunt; and the western boat and Bank fisheries of the south coast. For the purposes of this review it was found helpful to draw a distinction between “resident outport merchants” who lived the full range of their adult lives in rural Newfoundland and the “merchant gentry” whose outport residency was an episode in their business and family life which was otherwise substantially spent in the Old Country or in St. John’s. The resident group may be more worthy of consideration for the Province’s commemoration program. Existing commemorations tend to favour the merchant gentry. -

The Newfoundland and Labrador Gazette

NOTE: Attached to the end of Part II is a list of Statutes of Newfoundland and Labrador, 2009 as enacted up to May 28, 2009. No Subordinate Legislation received at time of printing THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GAZETTE PART I PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Vol. 84 ST. JOHN’S, FRIDAY, JULY 10, 2009 No. 28 CANADA-NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR ATLANTIC ACCORD IMPLEMENTATION NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR ACT NOTICE OF HEARING The C-NLOPB has appointed the Honourable Robert Wells, Q.C. as Commissioner of the Inquiry on Offshore Helicopter Safety. The Inquiry will be divided into two phases. The purpose of Phase I of the Inquiry is to determine and recommend to the C- NLOPB, improvements to the safety regime which in the opinion of the Commissioner would improve offshore helicopter safety to ensure that the risks of helicopter transportation of offshore workers is as low as is reasonably practicable in the Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Area. Phase II shall proceed upon completion of the Transportation Safety Board of Canada Investigation into Cougar Helicopter Sikorsky S92-A Crash. The Commissioner’s mandate will be to inquire into, report on and make recommendations in respect of matters relating to the safety of offshore workers in the context of Operator’s accountability for transport, escape, evacuation and rescue procedures while travelling by helicopter over water to installations in the Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Area, in compliance with occupational health and safety principles and best industry practices. Specifically, the Commissioner shall inquire into, report on and make recommendations in respect of safety plan requirements for Operators and the role that Operators play in ensuring that their safety plans are maintained by helicopter operators; search and rescue obligations of helicopter operators by way of contractual undertakings or legislative or regulatory requirements; and the role of the C-NLOPB and other regulators in ensuring compliance with legislative requirements in respect of worker safety. -

Urbanized Areas by Nazarene District

Population Centres by Nazarene District, 2020 District: Canada Atlantic Population Centres with Nazarene Presence 2016 Population Active Full Worship Churches Adherents Population Centre on District Churches Members Average Adherents per 100,000 per 100,000 Halifax, NS 316,701 2 42 51 84 0.6 27 Moncton, NB 108,620 3 405 151 405 2.8 373 Fredericton, NB 59,405 2 17 47 104 3.4 175 Charlottetown, PE 44,739 1 144 103 150 2.2 335 Truro, NS 22,954 2 33 30 40 8.7 174 New Glasgow, NS 18,665 1 118 98 170 5.4 911 Summerside, PE 13,814 1 93 119 217 7.2 1,571 Kingston ‐ Greenwood, NS 6,879 1 36 36 85 14.5 1,236 Windsor, NS 5,248 1 58 78 207 19.1 3,944 Population Centres with No Nazarene Presence 2016 Population Population Centre on District St. John's, NL 178,427 Saint John, NB 58,341 Cape Breton ‐ Sydney, NS 29,904 Quispamsis ‐ Rothesay, NB 24,445 Corner Brook, NL 19,547 Glace Bay, NS 17,556 Bathurst, NB 15,557 Sydney Mines, NS 12,823 Kentville, NS 12,088 Edmundston, NB 12,086 Grand Falls‐Windsor, NL 12,046 Chatham ‐ Douglastown, NB 11,329 Gander, NL 10,220 Amherst, NS 9,550 Oromocto, NB 8,805 * Campbellton, NB‐QC 8,780 Labrador City, NL 8,622 Bridgewater, NS 8,532 New Waterford, NS 7,344 Yarmouth, NS 7,217 Population Centres are recognized by Statistics Canada as communities of at least 1,000 people with at least 400 per square kilometer.