Where Ambassadors Go

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Irvine X-Men Fan Club.Pdf

UC Irvine Tossups 4/17/043:51 PM Technophobia 4: Massive Quizbowl Overdose Tossups by DC Irvine X-Men Fan Club (Willie Chen, Jun Tokeshi, and Matt Adams) 1. 1bis man befriended Leonardo DiCaprio while they were making the 'IV series "Parenthood." Now, ignorant girls refer to him simply as "Leo's friend." His first lead role was in the 'IV sitcom "Great Scott!" He played a hitchhiker in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Harvey Stem in Deconstructing Harry, and Paul Hood in The Ice Storm. For 10 points--identify this talented young actor who starred opposite Reese Witherspoon as Bud Parker in Pleasantville. answer: Tobey Maguire 2. In one of her novels, this author tells the stol)' ofWhittman Ah Sing, a San Francisco hippie who tries to stage an epic production of interwoven Chinese novels and folktales. In another novel, subtitled "Memoirs ofa Girlhood among Ghosts," this author retells the stories of Fa Mu-Lan and the woman who killed herself by jumping into a well. For 10 points--who is this Chinese-American author of Tripmaster Monkey and The Woman Warrior? answer: Maxine Hong Kingston 3. The northern part of this countl)' contains many hot springs and has its highest peak at Mt. R1;!apehu. The southern part contains many glaciers and mountain lakes in the Southern Alps, with the highest point at Mt. Cook. For 10 points--identify this island nation composed of the world's 12th and 15th largest islands, which are separated by the Cook Strait. answer: New Zealand 4. He was the alternate US representative to the United Nations General Assembly and a member of the US delegation to the UN Human Rights Commission. -

It Deserved an Oscar Diplomatic Reporting Today

PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION JULY-AUGUST 2014 DIPLOMATIC REPORTING TODAY IT DESERVED AN OSCAR A BIRTHDAY PARTY FOR THE FOREIGN SERVICE FOREIGN July-August 2014 SERVICE Volume 91, No. 7-8 AFSA NEWS FOCUS EMBASSY REPORTING TODAY Gala 90th-Anniversary Celebration / 45 The Art of Political Reporting / 22 State VP Voice: Despite the challenges, reporting from the field—in whatever form it takes— Bidding and 360s / 46 is still the indispensable ingredient of any meaningful foreign policy discussion. USAID VP Voice: FS Benefits–How Do State and USAID Compare? / 47 BY DAN LAWTON AFSA Welcomes New Staff Members / 48 Diplomatic Reporting: Adapting Two New Reps Join AFSA Board / 48 to the Information Age / 26 Speaker Partnership with USC / 49 2014 AFSA Award Winners / 49 While technology enhances brainpower, it is no substitute for the seasoned diplomat’s powers of observation and assessment, argues this veteran consumer Issue Brief: The COM Guidelines / 50 of diplomatic reporting. Expert on Professions Kicks Off New AFSA Forum / 53 BY JOHN C. GANNON The 2014 Kennan Writing Award / 56 2014 Merit Award Winners / 57 A Selection of Views from Practitioners / 31 AFSA Files MSI Implementation Hitting the Ball Dispute / 61 CHRISTOPHER W. BISHOP On the Hill: Who Said It’s All About Congress? / 62 Bring in the Noise–Using Digital Technology to Promote Peace and Security USAID Mission Directors’ DANIEL FENNELL Happy Hour / 63 Inside a U.S. Embassy: Yet The Value-Added of Networking Another Press Run / 63 CHRISTOPHER MARKLEY NYCE Why You Need a Household Inventory / 64 The Three Amigos–South Korea, Colombia and Panama Trade Agreements Federal Benefits Event Draws IVAN RIOS a Full House / 65 Political Reporting: Then and Now–and Looking Ahead COLUMNS KATHRYN HOFFMAN AND SAMUEL C. -

Open Hearing: Nomination of Gina Haspel to Be the Director of the Central Intelligence Agency

S. HRG. 115–302 OPEN HEARING: NOMINATION OF GINA HASPEL TO BE THE DIRECTOR OF THE CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY HEARING BEFORE THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION WEDNESDAY, MAY 9, 2018 Printed for the use of the Select Committee on Intelligence ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 30–119 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 VerDate Sep 11 2014 14:25 Aug 20, 2018 Jkt 030925 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\DOCS\30119.TXT SHAUN LAP51NQ082 with DISTILLER SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE [Established by S. Res. 400, 94th Cong., 2d Sess.] RICHARD BURR, North Carolina, Chairman MARK R. WARNER, Virginia, Vice Chairman JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California MARCO RUBIO, Florida RON WYDEN, Oregon SUSAN COLLINS, Maine MARTIN HEINRICH, New Mexico ROY BLUNT, Missouri ANGUS KING, Maine JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma JOE MANCHIN III, West Virginia TOM COTTON, Arkansas KAMALA HARRIS, California JOHN CORNYN, Texas MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky, Ex Officio CHUCK SCHUMER, New York, Ex Officio JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona, Ex Officio JACK REED, Rhode Island, Ex Officio CHRIS JOYNER, Staff Director MICHAEL CASEY, Minority Staff Director KELSEY STROUD BAILEY, Chief Clerk (II) VerDate Sep 11 2014 14:25 Aug 20, 2018 Jkt 030925 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 C:\DOCS\30119.TXT SHAUN LAP51NQ082 with DISTILLER CONTENTS MAY 9, 2018 OPENING STATEMENTS Burr, Hon. Richard, Chairman, a U.S. Senator from North Carolina ................ 1 Warner, Mark R., Vice Chairman, a U.S. Senator from Virginia ........................ 3 WITNESSES Chambliss, Saxby, former U.S. -

Hormel, James C. (B

Hormel, James C. (b. 1933) by Linda Rapp Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2004, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com James C. Hormel has a distinguished record as a philanthropist and a proponent of the cause of gay rights. His nomination to become the first openly gay ambassador from the United States drew criticism from conservative groups. A handful of Republican senators managed to forestall his confirmation for almost two years. Hormel comes from a prosperous family. In 1891 his German-born grandfather, George Hormel, founded Hormel Foods, which has grown into a leading meat packing company. Among its best-known products is Spam. James Catherwood Hormel was born on January 1, 1933 in Austin, Minnesota and grew up on the family estate there. He graduated from Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania with a B.A. in history in 1955. He went on to the University of Chicago Law School, where he earned his law degree in 1958. Hormel remained to teach in the law school at Chicago, eventually becoming dean of students. Hormel married in 1955, but a decade later he and his wife decided to divorce, mainly because of Hormel's sexual orientation. The couple have remained good friends, however, and Hormel has always enjoyed an excellent relationship with their son and four daughters. Hormel began a long-term relationship with artist Larry Soule in the early 1970s. The couple lived together for eighteen years. After sojourns in New York and Kauai, Hormel moved to San Francisco in 1976. There he founded Equidex, a company that manages his family's investments and philanthropic projects. -

The Iran Nuclear Deal: What You Need to Know About the Jcpoa

THE IRAN NUCLEAR DEAL: WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT THE JCPOA wh.gov/iran-deal What You Need to Know: JCPOA Packet The Details of the JCPOA • FAQs: All the Answers on JCPOA • JCPOA Exceeds WINEP Benchmarks • Timely Access to Iran’s Nuclear Program • JCPOA Meeting (and Exceeding) the Lausanne Framework • JCPOA Does Not Simply Delay an Iranian Nuclear Weapon • Tools to Counter Iranian Missile and Arms Activity • Sanctions That Remain In Place Under the JCPOA • Sanctions Relief — Countering Iran’s Regional Activities What They’re Saying About the JCPOA • National Security Experts and Former Officials • Regional Editorials: State by State • What the World is Saying About the JCPOA Letters and Statements of Support • Iran Project Letter • Letter from former Diplomats — including five former Ambassadors to Israel • Over 100 Ambassador letter to POTUS • US Conference of Catholic Bishops Letter • Atlantic Council Iran Task Force Statement Appendix • Statement by the President on Iran • SFRC Hearing Testimony, SEC Kerry July 14, 2015 July 23, 2015 • Key Excerpts of the JCPOA • SFRC Hearing Testimony, SEC Lew July 23, 2015 • Secretary Kerry Press Availability on Nuclear Deal with Iran • SFRC Hearing Testimony, SEC Moniz July 14, 2015 July 23, 2015 • Secretary Kerry and Secretary Moniz • SASC Hearing Testimony, SEC Carter Washington Post op-ed July 29, 2015 July 22, 2015 THE DETAILS OF THE JCPOA After 20 months of intensive negotiations, the U.S. and our international partners have reached an historic deal that will verifiably prevent Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon. The United States refused to take a bad deal, pressing for a deal that met every single one of our bottom lines. -

INDO 50 0 1106971426 29 60.Pdf (1.608Mb)

A m e r ic a n " L o w P o s t u r e " P o l ic y t o w a r d In d o n e s ia in t h e M o n t h s L e a d in g u p t o t h e 1965 "C o u p " 1 Frederick Bunnell Introduction This article seeks to contribute to the reconstruction, explanation, and evaluation of the Johnson Administration's response to President Sukarno's radicalization of Indonesia's do mestic politics and foreign policy in the first nine months of 1965 leading up to the abortive "coup" on October 1,1965. The focus throughout is on both the thinking and the politics of what can be termed "the 1965 Indonesia policy group."2 That unofficial group was the informal constellation of US officials both in Indonesia (in the Embassy-based country team)3 and in Washington (in the *This article has enjoyed a long, troubled odyssey. Growing out of intermittent research on American-Indonesian relations dating back to my doctoral dissertation field research in Jakarta in 1963-1965, the substance of the article, including its primary conclusions, was presented in papers at the August 1979 Indonesian Studies Con ference in Berkeley and the March 1980 International Studies Association Conference in Los Angeles. I am in debted to the American Philosophical Society, the Lyndon Baines Johnson Foundation, and the Vassar College Faculty Research Committee for grants in 1976-1979 which facilitated the brunt of the archival and interview re search undergirding the article. -

Americas Society and the Council of the Americas — President and Chief Executive Officer

Senior Team Susan L. Segal Americas Society and the Council of the Americas — President and Chief Executive Officer uniting opinion leaders to exchange ideas and create Eric P. Farnsworth solutions to the challenges of the Americas today Vice President Peter J. Reilly Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Nancy E. Anderson Americas Society Senior Director, Miami Americas Society (AS) is the premier forum dedicated to education, Ana Gilligan debate, and dialogue in the Americas. Its mission is to foster an Senior Director, Corporate Sponsorship understanding of the contemporary political, social, and economic issues Ragnhild Melzi confronting Latin America, the Caribbean, and Canada, and to increase Senior Director, Public Policy Programs public awareness and appreciation of the diverse cultural heritage and Corporate Relations of the Americas and the importance of the Inter-American relationship.1 Christopher Sabatini Senior Director, Policy and Editor-in-Chief, Americas Quarterly Council of the Americas Andrea Sanseverino Galan Council of the Americas (COA) is the premier international business Senior Director, Foundation and Institutional Giving organization whose members share a common commitment to economic and social development, open markets, the rule of law, and democracy Pola Schijman throughout the Western Hemisphere. The Council’s membership consists Senior Director, Special Events of leading international companies representing a broad spectrum Carin Zissis of sectors including banking and finance, consulting services, -

United Nations List of Delegations to the Second High-Level United

United Nations A/CONF.235/INF/2 Distr.: General 30 August 2019 Original: English Second High-level United Nations Conference on South-South Cooperation Buenos Aires, 20–22 March 2019 List of delegations to the second High-level United Nations Conference on South-South Cooperation 19-14881 (E) 110919 *1914881* A/CONF.235/INF/2 I. States ALBANIA H.E. Mr. Gent Cakaj, Acting Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs H.E. Ms. Besiana Kadare, Ambassador, Permanent Representative Mr. Dastid Koreshi, Chief of Staff of the Acting Foreign Minister ALGERIA H.E. Mr. Abdallah Baali, Ambassador Counsellor, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Alternate Head of Delegation H.E. Mr. Benaouda Hamel, Ambassador of Algeria in Argentina, Embassy of Algeria in Argentina Representatives Mr. Nacim Gaouaoui, Deputy Director, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Mr. Zoubir Benarbia, First Secretary, Permanent Mission of Algeria to the United Nations Mr. Mohamed Djalel Eddine Benabdoun, First Secretary, Embassy of Algeria in Argentina ANDORRA Mrs. Gemma Cano Berne, Director for Multilateral Affairs and Cooperation Mrs. Julia Stokes Sada, Desk Officer for International Cooperation for Development ANGOLA H.E. Mr. Manuel Nunes Junior, Minister of State for Social and Economic Development, Angola Representatives H.E. Mr. Domingos Custodio Vieira Lopes, Secretary of State for International Cooperation and Angolan Communities, Angola H.E. Ms. Maria de Jesus dos Reis Ferreira, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission of Angola to the United Nations ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA H.E. Mr. Walton Alfonso Webson, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission Representative Mr. Claxton Jessie Curtis Duberry, Third Secretary, Permanent Mission 2/42 19-14881 A/CONF.235/INF/2 ARGENTINA H.E. -

Not Friend, Not Foe Reassessing U.S.-China Great Power Competition with the Hydrangea Framework

OCTOBER 2020 Not Friend, Not Foe Reassessing U.S.-China Great Power Competition with the Hydrangea Framework Yilun Zhang Jessica L. Martin October 2020 I About ICAS The Institute for China-America Studies is an independent think tank funded by the Hainan Freeport Research Foundation in China. Based in the heart of Washington D.C., ICAS is uniquely situated to facilitate the exchange of ideas and people between China and the United States. We achieve this through research and partnerships with institutions and scholars in both countries, in order to provide a window into their respective worldviews. ICAS focuses on key issue areas in the U.S.-China relationship in need of greater mutual understanding. We identify promising areas for strengthening bilateral cooperation in the spheres of maritime security, Asia-Pacific economics, trade, strategic stability, international relations as well as global governance issues, and explore avenues for improving this critical bilateral relationship. ICAS is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization. ICAS takes no institutional positions on policy issues. The views expressed in this document are those of the author(s) alone. © 2020 by the Institute for China-America Studies. All rights reserved. Institute for China-America Studies 1919 M St. NW Suite 310 Washington, DC 20036 202 290 3087 | www.chinaus-icas.org II Not Friend, Not Foe Contents IV - VI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY VIII ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS & ABOUT THE AUTHORS 1-6 PART I | Then...and Now 7-47 PART II | The Current State: Now...What Now? 48-68 PART III | What Next: The Hydrangea Framework ENDNOTES October 2020 III Executive Summary he relationship between the United States and China has been in a state of flux for decades, but the tensions and rhetoric of the last few years appears to have left the Tbilateral relationship tainted and semi-hostile. -

The Country Team and Local Staff Role | Excerpt from Inside a U.S. Embassy

PART II Foreign Service Work and Life: Embassy, Employee, Family By Shawn Dorman THE EMBASSY AND THE COUNTRY TEAM mbassies are located in the capital city of each country with which the United States has official relations, and serve as headquarters for U.S. gov - Eernment representation overseas. U.S. consulates are ancillary government offices in cities other than the capital. American and local employees serving in U.S. embassies and consulates work under the leadership of an ambassador to conduct diplomatic relations with the host country. The Department of State is the lead agency for conducting U.S. diplomacy and the ambassador, appointed by the U.S. president, reports to the Secretary of State. Diplomatic relations among nations, including diplomatic immunity and the inviolability of embassies, follow procedures framed by the 1961 Vienna Convention on the Conduct of Diplomatic Relations and Optional Protocols, ratified by the U.S. in 1969. The foreign affairs agencies that make up the Foreign Service—the Department of State, the U.S. Agency for International Development, the Foreign Commercial Service, the Foreign Agricultural Service, and the International Broadcasting Bureau—are part of the overall U.S. mission in a country and usually have their offices inside the embassy. Each embassy can also be home to the offices of other U.S. government agencies and departments, in some countries as many as 40 dif - ferent entities. Agencies with a significant overseas presence include the Department of Defense, the Central Intelligence Agency, the Drug Enforcement Agency, the Treasury Department, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Department of Homeland Security. -

The Foreign Service Journal, April 2014

PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION APRIL 2014 GREENING EMBASSIES CHIEf-Of-MISSION GUIDELINES HOW H.A. GILES LEARNED CHINESE FOREIGN April 2014 SERVICE Volume 91, No. 4 AFSA NEWS FOCUS GREENING EMBASSIES AFSA Releases Chief-of-Mission Guidelines / 45 Eco-Diplomacy: Building the Foundation / 20 VP Voice State: Collaborating with Our Partner Organizations / 46 U.S. embassies and consulates around the world are becoming showcases VP Voice Retiree: Retirement for American leadership in best practices and sustainable technology. Begins Before Retirement / 47 BY DONNA M. MCINTIRE VP Voice FCS: The Budget Resource Merry-Go-Round / 48 The Greening Diplomacy Initiative: Chief-of-Mission Guidelines / 49 Capturing Innovation / 24 AFSA Hosts Chiefs of Mission / 51 AFSA On the Hill: State’s homegrown Greening Diplomacy Initiative relies on seeding, Beyond Advocacy Day / 52 harvesting, sifting, implementing and sharing employees’ innovations New Association Management and ideas, large and small. System for AFSA / 53 BY CAROLINE D’ANGELO AFSA VP Meets with Florida Retirees / 54 The League of Green Embassies: 2013 Sinclaire Award Recipients / 54 AFSA Book Notes: American Leadership in Sustainability / 30 America’s First Globals / 55 A coalition of more than 100 U.S. embassies and consulates worldwide AFSA Partners with United Nations shares ideas and practical experience in the field. Association / 56 BY JOHN DAVID MOLESKY FSJ Editor-in-Chief Steps Down / 56 AFSA and DACOR Salute U.S. Marine Security Guards / 57 Finns Take the LEED in Green Embassy Design / 35 The Foreign Service Family: The Finnish embassy in Washington, D.C., is a green building that The Packout and Me / 59 was ahead of its time. -

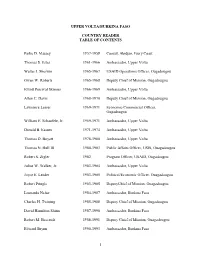

Table of Contents

UPPER VOLTA/BURKINA FASO COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Parke D. Massey 1957-1958 Consul, Abidjan, Ivory Coast Thomas S. Estes 1961-1966 Ambassador, Upper Volta Walter J. Sherwin 1965-1967 USAID Operations Officer, Ougadougou Owen W. Roberts 1965-1968 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou Elliott Percival Skinner 1966-1969 Ambassador, Upper Volta Allen C. Davis 1968-1970 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou Lawrence Lesser 1969-1971 Economic/Commercial Officer, Ougadougou William E. Schaufele, Jr. 1969-1971 Ambassador, Upper Volta Donald B. Easum 1971-1974 Ambassador, Upper Volta Thomas D. Boyatt 1978-1980 Ambassador, Upper Volta Thomas N. Hull III 1980-1983 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Ouagadougou Robert S. Zigler 1982 Program Officer, USAID, Ougadougou Julius W. Walker, Jr. 1983-1984 Ambassador, Upper Volta Joyce E. Leader 1983-1985 Political/Economic Officer, Ouagadougou Robert Pringle 1983-1985 DeputyChief of Mission, Ouagadougou Leonardo Neher 1984-1987 Ambassador, Burkina Faso Charles H. Twining 1985-1988 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou David Hamilton Shinn 1987-1990 Ambassador, Burkina Faso Robert M. Beecrodt 1988-1991 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ouagadougou Edward Brynn 1990-1993 Ambassador, Burkina Faso 1 PARKE D. MASSEY Consul Abidjan, Ivory Coast (1957-1958) Parke D. Massey was born in New York in 1920. He graduated from Haverford College with a B.A. and Harvard University with an M.P.A. He also served in the U.S. Army from 1942 to 1946 overseas. After entering the Foreign Service in 1947, Mr. Massey was posted in Mexico City, Genoa, Abidjan, and Germany. While in USAID, he was posted in Nicaragua, Panama, Bolivia, Chile, Haiti, and Uruguay.