The Complexity of Intersectionality Author(S): Leslie Mccall Source: Signs, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

171 Subverting Lévi-Strauss's Structuralism

Humanitas, 2020; 8(16): 171-186 http://dergipark.gov.tr/humanitas ISSN: 2645-8837 DOI: 10.20304/humanitas.729077 SUBVERTING LÉVI-STRAUSS’S STRUCTURALISM: READING GENDER TROUBLE AS “TWISTED BRICOLAGE” Anlam FİLİZ1 Abstract This article critically analyzes Judith Butler’s presentation of Claude Lévi-Strauss in her book Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1999). In this book, Butler criticizes feminists for employing Lévi-Strauss’s binary oppositions and their use of the sex/gender binary in their critique of patriarchy. Butler’s analysis provides a fruitful lens to understand how gender operates. However, as the article shows, this analysis relies on a misrepresentation of Lévi-Strauss’s take on these dualities. Employing Lévi-Strauss’s term “bricolage,” the article reads Butler’s misinterpretation as a twisted form of bricolage, which destabilizes certain assumptions in Lévi-Strauss’s structuralism. The article presents an example of how Lévi-Strauss’s structural theory has influenced not only feminist theory but also its critique. The article also aims at providing an alternative way to understand influential gender theorist Judith Butler’s misinterpretation of other scholars. 171 Keywords: Claude Lévi-Strauss, Judith Butler, Gender Trouble, twisted bricolage, structuralism, subversion LÉVI-STRAUSS’UN YAPISALCILIĞINI ALTÜST ETMEK: CİNSİYET BELASI’NI “BÜKÜLMÜŞ BRİCOLAGE” OLARAK OKUMAK Öz Bu makale, Judith Butler’ın Cinsiyet Belası: Feminizm ve Kimliğin Altüst Edilmesi (1999) adlı kitabında etkili yapısal antropolog Claude Lévi-Strauss’u sunuşunu eleştirel bir şekilde analiz eder. Bu kitapta Butler feministleri, ataerkil düzen eleştirilerinde Lévi-Strauss’un ikili karşıtlıklarını ve cinsiyet/toplumsal cinsiyet ikiliğini kullandıkları için eleştirir. Butler’ın analizi, toplumsal cinsiyetin nasıl işlediğini anlamak için verimli bir mercek sağlar. -

Rethinking Feminist Ethics

RETHINKING FEMINIST ETHICS The question of whether there can be distinctively female ethics is one of the most important and controversial debates in current gender studies, philosophy and psychology. Rethinking Feminist Ethics: Care, Trust and Empathy marks a bold intervention in these debates by bridging the ground between women theorists disenchanted with aspects of traditional ‘male’ ethics and traditional theorists who insist upon the need for some ethical principles. Daryl Koehn provides one of the first critical overviews of a wide range of alternative female/ feminist/feminine ethics defended by influential theorists such as Carol Gilligan, Annette Baier, Nel Noddings and Diana Meyers. She shows why these ethics in their current form are not defensible and proposes a radically new alternative. In the first section, Koehn identifies the major tenets of ethics of care, trust and empathy. She provides a lucid, searching analysis of why female ethics emphasize a relational, rather than individualistic, self and why they favor a more empathic, less rule-based, approach to human interactions. At the heart of the debate over alternative ethics is the question of whether female ethics of care, trust and empathy constitute a realistic, practical alternative to the rule- based ethics of Immanuel Kant, John Stuart Mill and John Rawls. Koehn concludes that they do not. Female ethics are plagued by many of the same problems they impute to ‘male’ ethics, including a failure to respect other individuals. In particular, female ethics favor the perspective of the caregiver, trustor and empathizer over the viewpoint of those who are on the receiving end of care, trust and empathy. -

Women and Gender Studies / Queer Theory

1 Women and Gender Studies / Queer Theory Please choose at least 60 to 67 texts from across the fields presented. Students are expected to familiarize themselves with major works throughout this field, balancing their particular interests with the need to prepare themselves broadly in the topic. First Wave Feminism 1. Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792) 2. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, “Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions” (1848) 3. Harriet Taylor, “Enfranchisement of Women” (1851) 4. Sojourner Truth, “Ain’t I a Woman?” (1851) 5. John Stuart Mill, The Subjection of Women (1869) 6. Susan B. Anthony, Speech after Arrest for Illegal Voting (1872) 7. Anna Julia Cooper, A Voice From the South (1892) 8. Charlotte Perkins, Women and Economics (1898) 9. Emma Goldman, The Traffic in Women and Other Essays on Feminism (1917) 10. Nancy Cott, The Grounding of Modern Feminism (1987) 11. Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own (1929) 12. Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (1953) Second Wave Feminism 13. Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique (1963) 14. Kate Millet, Sexual Politics (1969) 15. Phyllis Chesler, Women and Madness (1970) 16. Shulamith Firestone, The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution (1970) 17. Germaine Greer, The Female Eunuch (1970) 18. Brownmiller, Susan, Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape (1975) 19. Adrienne Rich, Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution (1976) 20. Mary Daly, Gyn/Ecology: The Metaethics of Radical Feminism (1978) 21. 22. Alice Echols, Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America 1967-75 (1989) Third Wave Feminism 23. Leslie Heywood and Jennifer Drake, eds., Third Wave Agenda: Being Feminist, Doing Feminism (1997) 24. -

Intersectionality: T E Fourth Wave Feminist Twitter Community

#Intersectionality: T e Fourth Wave Feminist Twitter Community Intersectionality, is the marrow within the bones of fem- Tegan Zimmerman (PhD, Comparative Literature, inism. Without it, feminism will fracture even further – University of Alberta) is an Assistant Professor of En- Roxane Gay (2013) glish/Creative Writing and Women’s Studies at Stephens College in Columbia, Missouri. A recent Visiting Fel- This article analyzes the term “intersectional- low in the Centre for Contemporary Women’s Writing ity” as defined by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw (1989, and the Institute of Modern Languages Research at the 1991) in relation to the digital turn and, in doing so, University of London, Zimmerman specializes in con- considers how this concept is being employed by fourth temporary women’s historical fiction and contempo- wave feminists on Twitter. Presently, little scholarship rary gender theory. Her book Matria Redux: Caribbean has been devoted to fourth wave feminism and its en- Women’s Historical Fiction, forthcoming from North- gagement with intersectionality; however, some notable western University Press, examines the concepts of ma- critics include Kira Cochrane, Michelle Goldberg, Mik- ternal history and maternal genealogy. ki Kendall, Ealasaid Munro, Lola Okolosie, and Roop- ika Risam.1 Intersectionality, with its consideration of Abstract class, race, age, ability, sexuality, and gender as inter- This article analyzes the term “intersectionality” as de- secting loci of discriminations or privileges, is now the fined by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in relation to the overriding principle among today’s feminists, manifest digital turn: it argues that intersectionality is the dom- by theorizing tweets and hashtags on Twitter. Because inant framework being employed by fourth wave fem- fourth wave feminism, more so than previous feminist inists and that is most apparent on social media, espe- movements, focuses on and takes up online technolo- cially on Twitter. -

GENDER TROUBLE Feminism and the Subversion of Identity

GENDER TROUBLE Feminism and the Subversion of Identity JUDITH BUTLER Routledge New York and London Preface (1999)." Judith Butler. Gender Trouble. New York: Routledge Press, 1999. Contents Preface (1999) vii Preface (1990) xxvii One Subjects of Sex/Gender/Desire 3 I “Women” as the Subject of Feminism 3 II The Compulsory Order of Sex/Gender/Desire 9 III Gender: The Circular Ruins of Contemporary Debate 11 IV Theorizing the Binary, the Unitary, and Beyond 18 V Identity, Sex, and the Metaphysics of Substance 22 VI Language, Power, and the Strategies of Displacement 33 Two Prohibition, Psychoanalysis, and the Production of the Heterosexual Matrix 45 I Structuralism’s Critical Exchange 49 2 of 17 Preface (1999)." Judith Butler. Gender Trouble. New York: Routledge Press, 1999. Preface (1999) Ten years ago I completed the manuscript of Gender Trouble and sent it to Routledge for publication. I did not know that the text would have as wide an audience as it has had, nor did I know that it would constitute a provocative “intervention” in feminist theory or be cited as one of the founding texts of queer theory. The life of the text has exceeded my intentions, and that is surely in part the result of the changing context of its reception. As I wrote it, I understood myself to be in an embattled and oppositional relation to certain forms of feminism, even as I understood the text to be part of feminism itself. I was writing in the tradition of immanent critique that seeks to provoke critical examination of the basic vocabulary of the movement of thought to which it belongs. -

Under Western Eyes Revisited: Feminist Solidarity Through

“Under Western Eyes” Revisited: Feminist Solidarity through Anticapitalist Struggles Author(s): Chandra Talpade Mohanty Reviewed work(s): Source: Signs, Vol. 28, No. 2 (Winter 2003), pp. 499-535 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/342914 . Accessed: 11/04/2012 00:27 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Signs. http://www.jstor.org Chandra Talpade Mohanty “Under Western Eyes” Revisited: Feminist Solidarity through Anticapitalist Struggles write this essay at the urging of a number of friends and with some trepidation, revisiting the themes and arguments of an essay written I some sixteen years ago. This is a difficult essay to write, and I undertake it hesitantly and with humility—yet feeling that I must do so to take fuller responsibility for my ideas, and perhaps to explain whatever influence they have had on debates in feminist theory. “Under Western Eyes” (1986) was not only my very first “feminist stud- ies” publication; it remains the one that marks my presence in the inter- national feminist community.1 I had barely completed my Ph.D. -

Butler: Gender Trouble Introduction Gender Trouble: Feminism And

Butler: Gender Trouble Introduction Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity has been published in 1990. Butler explores the way we shape our identity through social interactions. While Simone de Beauvoir stated :‘one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman’ Butler’s thoughts on gender could be sum up by ‘:‘one is not born, but rather becomes, a gender’. Gender can be defined as the way we express our sexuality ; for instance the way a female intends to express her sexuality will define her gender, and this can be also applied to any human being. The emphasis Butler puts on the will, on the intention, is important as she is not only suggesting that our gender is built and not received at birth, but is also pointing out the plasticity of our gender. Since it is an extension of our intention, our gender or what we express as sexual subject, is never fixed and can change over time. This intent gives birth to a performance, seen by Butler as the moment where we decide to express our gender. Therefore life is a succession of performances. Digeser confirms that, according to Butler, there exists no natural necessity to see bodies as ordered into distinct sexes: “whatever sense of giveness or facticity we may possess about our bodies is a matter of historically sedimented practices and performances. Our pleasures, desires and pains do not emanate from a prediscursive body. Rather, it is a matter of historical contingency that we see the body as we do”1. It is actually related to Nietzsche’s idea that there is no doer behind the deed: with Butler it is gender or sexuality that does not exist before it is performed in a social context. -

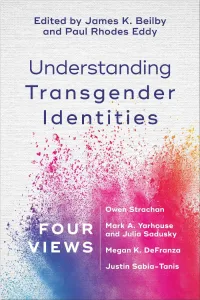

Understanding Transgender Identities

Understanding Transgender Identities FOUR VIEWS Edited by James K. Beilby and Paul Rhodes Eddy K James K. Beilby and Paul Rhodes Eddy, Understanding Transgender Identities Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2019. Used by permission. _Beilby_UnderstandingTransgender_BB_bb.indd 3 9/11/19 8:21 AM Contents Acknowledgments ix Understanding Transgender Experiences and Identities: An Introduction Paul Rhodes Eddy and James K. Beilby 1 Transgender Experiences and Identities: A History 3 Transgender Experiences and Identities Today: Some Issues and Controversies 13 Transgender Experiences and Identities in Christian Perspective 44 Introducing Our Conversation 53 1. Transition or Transformation? A Moral- Theological Exploration of Christianity and Gender Dysphoria Owen Strachan 55 Response by Mark A. Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky 84 Response by Megan K. DeFranza 90 Response by Justin Sabia- Tanis 95 2. The Complexities of Gender Identity: Toward a More Nuanced Response to the Transgender Experience Mark A. Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky 101 Response by Owen Strachan 131 Response by Megan K. DeFranza 136 Response by Justin Sabia- Tanis 142 3. Good News for Gender Minorities Megan K. DeFranza 147 Response by Owen Strachan 179 Response by Mark A. Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky 184 Response by Justin Sabia- Tanis 190 vii James K. Beilby and Paul Rhodes Eddy, Understanding Transgender Identities Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2019. Used by permission. _Beilby_UnderstandingTransgender_BB_bb.indd 7 9/11/19 8:21 AM viii Contents 4. Holy Creation, Wholly Creative: God’s Intention for Gender Diversity Justin Sabia- Tanis 195 Response by Owen Strachan 223 Response by Mark A. Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky 228 Response by Megan K. -

Judith Butler's Notion of Gender Performativity

Judith Butler’s Notion of Gender Performativity To What Extent Does Gender Performativity Exclude a Stable Gender Identity? J.T. Ton MSc 3702286 Faculty Humanities Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies Research Group Philosophy Date: 25-06-2018 Supervisor: Dr. J.E. de Jong Second reviewer: Dr. H.L.W. Hendriks Content ABSTRACT 2 INTRODUCTION 3 CONTEXT 3 RESEARCH QUESTION 3 METHOD 3 OUTLINE 4 1. IS THERE A DIFFERENCE BETWEEN GENDER AND SEX? 6 1.1 THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN GENDER AND SEX 6 1.2 BUTLER’S CRITIQUE OF THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN GENDER AND SEX 7 2. BUTLER’S NOTION OF GENDER PERFORMATIVITY 8 2.1 GENDER AS A SOCIAL CONSTRUCT 8 2.2 WHAT IT MEANS TO BE PERFORMATIVE 9 3. GENDER IDENTITY IS UNSTABLE 11 3.1 GENDER IDENTITY BEING UNSTABLE IS PROBLEMATIC 11 3.2 BUTLER’S EXAMPLE OF TRANSGENDER PEOPLE IS PROBLEMATIC 12 3.3 BUTLER’S EXAMPLE OF DRAG IS PROBLEMATIC 13 CONCLUSION 14 RESEARCH QUESTION 14 IMPLICATIONS IN A BROADER CONTEXT 15 METHOD 15 FURTHER RESEARCH 16 REFERENCES 17 APPENDIX 1 – FORM COGNIZANCE PLAGIARISM 18 1 Abstract The idea that gender is socially constructed has been accepted as common knowledge for a long time. This raises the question how does the construction of gender work. Judith Butler proposed that gender is performative. What does Butler (1999, 2004, 2011) mean when she uses the term gender performativity and to what extent does her view of gender being performative leave room for gender as a stable identity? In this thesis I argue that Butler’s notion of gender performativity implies that that gender identity is unstable. -

Developing a Corporeal Cyberfeminism: Beyond Cyberutopia

Article new media & society 12(6) 929–945 Developing a corporeal © The Author(s) 2010 Reprints and permission: http://www. cyberfeminism: beyond sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermission.nav DOI: 10.1177/1461444809350901 cyberutopia http://nms.sagepub.com Jessica E. Brophy University of Maine, USA Abstract This article discusses – and rejects – cyberutopia, an idealized theory of internet use that requires users to leave their bodies behind when online. The author instead calls for a cyberfeminist perspective in relation to studying the internet and other new media, centrally locating corporeality and embodiment. The underutilized concept of intra-agency is then employed to develop liminality in relation to the experience of going online. The author then outlines different versions of cyberfeminism and endorses that which addresses the relationships between the lived experiences of users and the technology itself. The article concludes with a call for theorists to expand and enrich the concepts used to study new media. Key words body, corporeality, cyberfeminism, dualism, gender, ntra-agency, liminality, torsion There are no utopian spaces anywhere except in the imagination. (Grosz, 2001: 19) Many of the early discourses surrounding the internet were utopian in nature, claiming that the disembodied nature of online spaces creates an egalitarian online experience, devoid of the discrimination attributed to the embodied experience. Feminists, in particular, have been quick to assess the possibilities of gender bending (Danet, 1998), online activism and connectivity (Hawthorne and Klein, 1999), though not all feminists have uncritically accepted the internet as a potentially utopian medium (Kramarae, 1998; Stabile, 1994). This article recognizes the importance of exploring the feminist potentialities of disembodied and dislocated online interaction, yet calls for a more nuanced approach to understanding the role of the body and materialism in studies of the internet. -

Cyberfeminist Theories and the Benefits of Teaching Cyberfeminist Literature

12 Cyberfeminist Theories and the Benefits of Teaching Cyberfeminist Literature Maya Zalbidea Paniagua Camilo José Cela University of Madrid Spain 1. Introduction In 2010 I had the opportunity to interview Julianne Pierce, writer and artist who took part of the first cyberfeminist group called VNS Matrix, at the conference "Riot Girls Techno Queen: the Rise of Laptop Generation Women" at the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid. When I asked her what she thought about present day cyberfeminism she answered melancholically: "Cyberfeminist movements are not as visible as they used to be during the 90s" ("Personal Interview with Julianne Pierce by Maya Zalbidea Paniagua" n/p) It is certainly true that the 80s and 90s supposed the golden age of cybercultures. Cybernetics arrived in the 1960s (Wiener 1968) but the glorious age of the Internet started in the 80s. In 1984 William Gibson coined the term cyberspace and anticipated the Internet revolution in his novel Neuromancer (1984). Other cyberpunk novels also illustrated a post-apocalyptic future such as: Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) by Philip K. Dick. Cyberpunk films such as Blade Runner (1982) and The Terminator (1984) received enormous impact. And some years later the Web was invented by British scientist Tim Berners-Lee in 1989, CERN publicized the new World Wide Web project in 1991, and during the 90s cyberfeminist theories and movements spread internationally. Unfortunately a climax of disillusion and a crisis of moral values has influenced negatively cyberfeminist thought, promoted by the idea that women in the third world cannot have access to the Internet, the battle between ecofeminists and cyberfeminists, and the ecological awareness of the difficulty to eliminate electronic garbage. -

Gender-Trouble-J-Butler-Pet-1.Pdf

Published in 1999 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 Published in Great Britain by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2002. Copyright © 1990, 1999 by Routledge Gender Trouble was originally published in the Routledge book series Thinking Gender, edited by Linda J. Nicholson. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Butler, Judith P. Gender trouble : feminism and the subversion of identity / Judith Butler. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Originally published: New York : Routledge, 1990. ISBN 0-415-92499-5 (pbk.) 1. Feminist theory. 2. Sex role. 3. Sex differences (Psychology) 4. Identity (Psychology) 5. Femininity. I.Title. HQ1154.B898 1999 305.3—dc21 99-29349 CIP ISBN 0-203-90275-0 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-90279-3 (Glassbook Format) 1 Subjects of Sex/Gender/Desire One is not born a woman,but rather becomes one. —Simone de Beauvoir Strictly speaking,“women”cannot be said to exist. —Julia Kristeva Woman does not have a sex. —Luce Irigaray The deployment of sexuality ...established this notion of sex. —Michel Foucault The category of sex is the political category that founds society as heterosexual. —Monique Wittig i. “Women” as the Subject of Feminism For the most part, feminist theory has assumed that there is some existing identity, understood through the category of women, who not only initiates feminist interests and goals within discourse, but consti- tutes the subject for whom political representation is pursued.