Feminist Futures: Trauma, the Post-9/11 World and a Fourth Feminism? E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

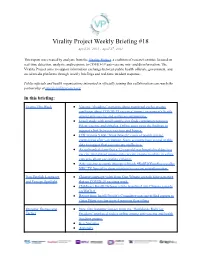

Virality Project Weekly Briefing #18 April 20, 2021 - April 27, 2021

Virality Project Weekly Briefing #18 April 20, 2021 - April 27, 2021 This report was created by analysts from the Virality Project, a coalition of research entities focused on real-time detection, analysis, and response to COVID-19 anti-vaccine mis- and disinformation. The Virality Project aims to support information exchange between public health officials, government, and social media platforms through weekly briefings and real-time incident response. Public officials and health organizations interested in officially joining this collaboration can reach the partnership at [email protected]. In this briefing: Events This Week ● Vaccine “shedding” narrative about menstrual cycles creates confusion about COVID-19 vaccines’ impact on women’s health among anti-vaccine and wellness communities. ● Israeli study with small sample size finds correlation between Pfizer vaccine and shingles. Online users twist the findings to suggest a link between vaccines and herpes. ● CDC reports 5,800 “breakthrough” cases of people getting coronavirus after vaccination. Some accounts have seized on this data to suggest that vaccines are ineffective. ● An unfounded claim that a 12-year-old was hospitalized due to a vaccine trial spread among anti-vaccine groups resulting in safety concerns about vaccinating children. ● Anti-vaccine accounts attempt to hijack #RollUpYourSleeves after NBC TV Special to draw attention to vaccine misinformation. Non-English Language ● Chinese language video from Guo Wengui spreads false narrative and Foreign Spotlight that no COVID-19 vaccines work. ● Children’s Health Defense article translated into Chinese spreads on WeChat. ● Report from Israeli People’s Committee uses unverified reports to claim Pfizer vaccine more dangerous than others Ongoing Themes and ● New film featuring footage from the “Worldwide Rally for Tactics Freedom” marketed widely online among anti-vaccine and health freedom groups. -

Feminism in the Twenty-First Century: Does It Need (Re)Branding? Maria Morelli University of Leicester

Volume 4(1) 2011 FEMINISMS: THE EVOLUTION Feminism in the Twenty-First Century: Does It Need (Re)branding? Maria Morelli University of Leicester ver the years, the media declared the death of feminism with headlines such as O ‘Feminism was something for our mothers’, in the Independent (Levenson 2009) and ‘Feminism outmoded and unpopular’, in the Guardian (Ward 2003); other headlines such as ‘Warning: Feminism is bad for your health’ in the Independent (Dobson 2007) or ‘Bra- burning feminism has reached burn-out’, in The Times (Frean 2003) have attached negative connotations to feminism. Similar headlines have been in and out the news since the 1980s. However, the evidence suggests that young women are formulating their own constructions of feminism as a way to carve out a personal space for the redefinition of their own identity. Following on from this and using the British and Italian situation as case studies, I shall provide evidence for the observation that an array of new feminist activities, including national networks, local groups, and blogs, has recently been formed. This article will demonstrate, first, that the feminist movement today is still very much alive and very much needed, and, secondly, that, even current activists are undeniably adopting methods that are different from those of their foremothers, this does not necessarily imply that feminism has ceased to exist. Although aspects of these issues have already been considered by earlier studies, this article does so from an interesting and original perspective by examining them through a diverse range of sources available within mainstream media: excerpts from newspapers, feminist blogs and the American TV series Sex and the City. -

(Re)Engaging Students with Feminism in a Postfeminist World

Teaching the Conflicts: (Re)Engaging Students with Feminism in a Postfeminist World MEREDITH A. LOVE AND BRENDA M. HELmbRECHT What happened to the dreams of a girl president She’s dancing in the video next to 50 Cent They travel in packs of two or three With their itsy bitsy doggies and their teeny-weeny tees Where, oh where, have the smart people gone? Maybe if I act like that, that guy will call me back Porno Paparazzi girl, I don’t wanna be a stupid girl Baby if I act like that, flipping my blond hair back Push up my bra like that, I don’t wanna be a stupid girl —Pink, “Stupid Girls” If representational visibility equals power, then almost-naked young white women should be running Western culture. —Peggy Phelan, Unmarked There is no question that the work of femi- all around” and a “World despaired, their nists has benefited the daily lives, health, only concern [is]: Will they fuck up my and financial status of many American hair?” Certainly, Pink is prone to hyper- women. In fact, some women’s lives have bole, but her questions resonate: do young been so improved that today’s younger women still dream of being world leaders, generation of women may not even know or have their ambitions been curtailed that “we’ve come a long way, baby” and, in lieu of the smaller achievements they perhaps even more importantly, that we can make with their buying power? Peggy still have a long way to go. Even pop cul- Phelan makes a similar point above, noting ture icons themselves, such as the musi- that “almost-naked young white women” cian Pink, recognize the current state of are given great visibility in our culture, gender politics, lamenting the fact that especially in advertisements, television, young women today are more concerned and film; yet it would be preposterous to with what they need to do and buy to suggest that their visibility instantly trans- maintain their image than they are with lates into power. -

Under Western Eyes Revisited: Feminist Solidarity Through

“Under Western Eyes” Revisited: Feminist Solidarity through Anticapitalist Struggles Author(s): Chandra Talpade Mohanty Reviewed work(s): Source: Signs, Vol. 28, No. 2 (Winter 2003), pp. 499-535 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/342914 . Accessed: 11/04/2012 00:27 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Signs. http://www.jstor.org Chandra Talpade Mohanty “Under Western Eyes” Revisited: Feminist Solidarity through Anticapitalist Struggles write this essay at the urging of a number of friends and with some trepidation, revisiting the themes and arguments of an essay written I some sixteen years ago. This is a difficult essay to write, and I undertake it hesitantly and with humility—yet feeling that I must do so to take fuller responsibility for my ideas, and perhaps to explain whatever influence they have had on debates in feminist theory. “Under Western Eyes” (1986) was not only my very first “feminist stud- ies” publication; it remains the one that marks my presence in the inter- national feminist community.1 I had barely completed my Ph.D. -

Engagement with False Content Producers Plummeted on Twitter and Facebook

Engagement with False Content Producers Plummeted on Twitter and Facebook Adrienne Goldstein Manipulative News Sites Accounted for a Record Share of Facebook Interactions Sites that gather and present information irresponsibly (according to the news-rating service NewsGuard) accounted for a record-high one-fifth of Facebook interactions with U.S.-based sitesi in the second quarter of 2021, while engagement with articles from outlets that repeatedly publish false content plummeted on Twitter and Facebook. This occurred amidst an overall decline in engagement with all types of sites. After all-time highs in engagement with both types of deceptive news outlets in 2020, sites that publish false content have seen their engagement drop at much higher rates than U.S.- based sites in general, likely as a result of account takedowns and changes in policies around COVID-19 misinformation and content moderation. The changes demonstrate that Facebook and Twitter have the tools to address disinformation. However, outlets that gather and present information irresponsibly without publishing false content present a special challenge to the platforms. These sites can help spread conspiracies theories about elections and vaccines, highlighting the need for what GMF Digital calls “democratic design” principles to promote transparency and civic information. • Amidst an overall decline in Facebook interactions with U.S.-based sites that began in the latter half of 2020, interactions with outlets that collect and present information irresponsibly dropped in the second quarter of 2021. They fell by slightly less than the drop in overall traffic (35 percent vs 38 percent) and by far less than a sample of 106 trustworthy sites with perfect NewsGuard ratings (56 percent) or sites that repeatedly publish false content (54 percent). -

The Scandalous Fall of Feminism and the ``First Black President''

Chapter 24 The Scandalous Fall of Feminism and the ``First Black President'' Melissa Deem Feminism is always on trial. The most recent indictments occurred during the popular coverage of the Clinton/Lewinsky affair. Ironically, this time feminism was called forth to defend itself against the charge of silence. One commentator argued that this latest indictment ``signifies the end of feminism as we know it.'' He continues, ``the once shrill voice of feminist outrage is suddenly, deafeningly still'' (Horowitz 1998). These comments represent a new trend within the popular discourses concerning feminism in the United States. This may be the first moment in history when feminists have been castigated for too little speech. The ``fall'' of Bill Clinton (which never came to completion but saturated the political public sphere for two long years) was accompanied by another antici- pated fall: the demise of feminism. Public discourse across the political spectrum heralded the ``death of feminism'' when commenting on the relative silence of feminists in regard to the Clinton/Lewinsky scandal. Feminism's ``silence'' has been found especially noteworthy when contrasted to the loud anti-Republican pedagogy concerning sex and power with which feminists trumped patriarchy during the earlier Clarence Thomas and Bob Packwood scandals. Feminism may be the most visibly culpable post-1960s political movement called into question by the discourses of the Clinton/Lewinsky scandal, but it is certainly not alone. Clinton has come to embody a set of complaints against feminism and post-1960s racial and class politics more generally. His embodi- ment of minoritarian politics has been striking. -

Vol. 12, No.2 / Spring 2006

THE JOURNAL OF THE ALABAMA WRITERS’ FORUM FIRST DRAFT• SPRING 2006 WAYNE GREENHAW 2006 HARPER LEE AWARD Recipient Capital City Hosts ALABAMA BOOK FESTIVAL A Young Writer to Watch NAOMI WOLF COASTAL WRITERS GO HOLLYWOOD FY 06 BOARD OF DIRECTORS BOARD MEMBER PAGE President LINDA HENRY DEAN Auburn Words have been my life. While other Vice-President ten-year-olds were swimming in the heat of PHILIP SHIRLEY Jackson, MS summer, I was reading Gone with the Wind on Secretary my screened-in porch. While my friends were JULIE FRIEDMAN giggling over Elvis, I was practicing the piano Fairhope and memorizing Italian musical terms and the Treasurer bios of each composer. I visited the local library DERRYN MOTEN Montgomery every week and brought home armloads of Writers’ Representative books. From English major in college to high JAMES A. BUFORD, JR. school English teacher in my early twenties, Auburn I struggled to teach the words of Shakespeare Writers’ Representative and Chaucer to inner-city kids who couldn’t LINDA C. SPALLA read. They learned to experience the word, even Huntsville Linda Spalla serves as Writers’ Repre- DARYL BROWN though they couldn’t read it. sentative on the AWF Executive Com- Florence Abruptly moving from English teacher to mittee. She is the author of Leading RUTH COOK a business career in broadcast television sales, Ladies and a frequent public speaker. Birmingham I thought perhaps my focus would be dif- JAMES DUPREE, JR. fused and words would lose their significance. Surprisingly, another world of words Montgomery appeared called journalism: responsibly chosen words which affected the lives of STUART FLYNN Birmingham thousands of viewers. -

Feminism and Victim Politics in Neoliberal Times Dr Rebecca Stringer

Feminism and Victim Politics in Neoliberal Times Dr Rebecca Stringer Space, Race Bodies keynote lecture, 8 December 2014 Thank you so much for the introduction Holly and inviting me to be the understudy today for this keynote. It’s a real pleasure to be here. It’s a really exciting conference and you’ve done so well at putting this together. Can you hear me alright? So well, while I cant fill the shoes of the keynote who was to speak this mourning, I can tell you about my book. So this is just a slide of the cover and I always like to note that the image here, which was a photograph by Valonia DeSuza is of the Dunedin “slut walk”. So you just see Dunedin on the right there. It’s nice to have that sense of local protest built into this project that I did in my years here. What else do I want to say about the photograph? A couple of people in this room contributed to placards for this march and this is what I’m kind of going to talk about today. You can’t talk about a book in 40min or all of the themes. So I’m going to kind of pick up some particular themes and speak to those and kind of give you the kernel of the argument as it were. So, this is where I’d begin, with this statement “we are not victims stop trying to rescue us”. So read the first slide in a conference presentation I attended recently, the presentation was given by a sex-worker activist. -

Women Against Feminism: Exploring Discursive Measures and Implications of Anti-Feminist Discourse

Globe: A Journal of Language, Culture and Communication, 2: 70-90 (2015) Women against feminism: Exploring discursive measures and implications of anti-feminist discourse Alex Phillip Lyng Christiansen, Aalborg University Ole Izard Høyer, Aalborg University Abstract: The present paper studies anti-feminist discourse within the tumblr-based group Women Against Feminism, and explores how the sentiments of these anti-feminists, as expressed in a multi-modal format, may help to understand the difficulty feminism has with gathering support from its female audience. The textual corpus, gathered through the site, is analysed with methods inspired by Fairclough's 2012 version of CDA, focused on discovering social issues within feminism as it relates to a female audience. By considering implicature and counter-discourse, the analysis demonstrates that anti-feminists perceive feminists as victimising the female population and depriving them of agency, and call for feminism to consider their viewpoint. Conclusively, the created perception of victimisation then serves to illustrate how language works to construe modern feminist discourse in a negative light, and how this may further hinder feminism in reaching the audience it desires. Keywords: Antifeminism, counter-discourse, Critical Discourse Analysis, victimisation. 1. Introduction Women have real reasons to fear feminism, and we do young women no service if we suggest to them that feminism itself is safe. It is not. To stand opposed to your culture, to be critical of institutions, behaviors, discourses--when it is so clearly not in your immediate interest to do so--asks a lot of a young person, of any person. At its best, the feminist challenging of individualism, of narrow notions of freedom, is transformative, exhilarating, empowering. -

Judith Butler's Notion of Gender Performativity

Judith Butler’s Notion of Gender Performativity To What Extent Does Gender Performativity Exclude a Stable Gender Identity? J.T. Ton MSc 3702286 Faculty Humanities Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies Research Group Philosophy Date: 25-06-2018 Supervisor: Dr. J.E. de Jong Second reviewer: Dr. H.L.W. Hendriks Content ABSTRACT 2 INTRODUCTION 3 CONTEXT 3 RESEARCH QUESTION 3 METHOD 3 OUTLINE 4 1. IS THERE A DIFFERENCE BETWEEN GENDER AND SEX? 6 1.1 THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN GENDER AND SEX 6 1.2 BUTLER’S CRITIQUE OF THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN GENDER AND SEX 7 2. BUTLER’S NOTION OF GENDER PERFORMATIVITY 8 2.1 GENDER AS A SOCIAL CONSTRUCT 8 2.2 WHAT IT MEANS TO BE PERFORMATIVE 9 3. GENDER IDENTITY IS UNSTABLE 11 3.1 GENDER IDENTITY BEING UNSTABLE IS PROBLEMATIC 11 3.2 BUTLER’S EXAMPLE OF TRANSGENDER PEOPLE IS PROBLEMATIC 12 3.3 BUTLER’S EXAMPLE OF DRAG IS PROBLEMATIC 13 CONCLUSION 14 RESEARCH QUESTION 14 IMPLICATIONS IN A BROADER CONTEXT 15 METHOD 15 FURTHER RESEARCH 16 REFERENCES 17 APPENDIX 1 – FORM COGNIZANCE PLAGIARISM 18 1 Abstract The idea that gender is socially constructed has been accepted as common knowledge for a long time. This raises the question how does the construction of gender work. Judith Butler proposed that gender is performative. What does Butler (1999, 2004, 2011) mean when she uses the term gender performativity and to what extent does her view of gender being performative leave room for gender as a stable identity? In this thesis I argue that Butler’s notion of gender performativity implies that that gender identity is unstable. -

How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman Rachel F

Hofstra Law Review Volume 33 | Issue 1 Article 5 2004 How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman Rachel F. Moran Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Moran, Rachel F. (2004) "How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman," Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 33: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol33/iss1/5 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moran: How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman HOW SECOND-WAVE FEMINISM FORGOT THE SINGLE WOMAN Rachel F. Moran* I cannot imagine a feminist evolution leading to radicalchange in the private/politicalrealm of gender that is not rooted in the conviction that all women's lives are important, that the lives of men cannot be understoodby burying the lives of women; and that to make visible the full meaning of women's experience, to reinterpretknowledge in terms of that experience, is now the most important task of thinking.1 America has always been a very married country. From early colonial times until quite recently, rates of marriage in our nation have been high-higher in fact than in Britain and western Europe.2 Only in 1960 did this pattern begin to change as American men and women married later or perhaps not at all.3 Because of the dominance of marriage in this country, permanently single people-whether male or female-have been not just statistical oddities but social conundrums. -

Developing a Corporeal Cyberfeminism: Beyond Cyberutopia

Article new media & society 12(6) 929–945 Developing a corporeal © The Author(s) 2010 Reprints and permission: http://www. cyberfeminism: beyond sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermission.nav DOI: 10.1177/1461444809350901 cyberutopia http://nms.sagepub.com Jessica E. Brophy University of Maine, USA Abstract This article discusses – and rejects – cyberutopia, an idealized theory of internet use that requires users to leave their bodies behind when online. The author instead calls for a cyberfeminist perspective in relation to studying the internet and other new media, centrally locating corporeality and embodiment. The underutilized concept of intra-agency is then employed to develop liminality in relation to the experience of going online. The author then outlines different versions of cyberfeminism and endorses that which addresses the relationships between the lived experiences of users and the technology itself. The article concludes with a call for theorists to expand and enrich the concepts used to study new media. Key words body, corporeality, cyberfeminism, dualism, gender, ntra-agency, liminality, torsion There are no utopian spaces anywhere except in the imagination. (Grosz, 2001: 19) Many of the early discourses surrounding the internet were utopian in nature, claiming that the disembodied nature of online spaces creates an egalitarian online experience, devoid of the discrimination attributed to the embodied experience. Feminists, in particular, have been quick to assess the possibilities of gender bending (Danet, 1998), online activism and connectivity (Hawthorne and Klein, 1999), though not all feminists have uncritically accepted the internet as a potentially utopian medium (Kramarae, 1998; Stabile, 1994). This article recognizes the importance of exploring the feminist potentialities of disembodied and dislocated online interaction, yet calls for a more nuanced approach to understanding the role of the body and materialism in studies of the internet.