Post-Wagnerian Concepts in French Vocal Music and Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

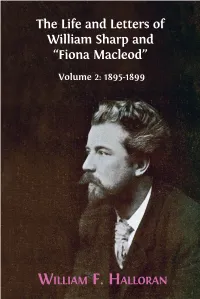

The Life and Letters of William Sharp and “Fiona Macleod”

The Life and Letters of William Sharp and “Fiona Macleod” Volume 2: 1895-1899 W The Life and Letters of ILLIAM WILLIAM F. HALLORAN William Sharp and What an achievement! It is a major work. The lett ers taken together with the excellent H F. introductory secti ons - so balanced and judicious and informati ve - what emerges is an amazing picture of William Sharp the man and the writer which explores just how “Fiona Macleod” fascinati ng a fi gure he is. Clearly a major reassessment is due and this book could make it ALLORAN happen. Volume 2: 1895-1899 —Andrew Hook, Emeritus Bradley Professor of English and American Literature, Glasgow University William Sharp (1855-1905) conducted one of the most audacious literary decep� ons of his or any � me. Sharp was a Sco� sh poet, novelist, biographer and editor who in 1893 began The Life and Letters of William Sharp to write cri� cally and commercially successful books under the name Fiona Macleod. This was far more than just a pseudonym: he corresponded as Macleod, enlis� ng his sister to provide the handwri� ng and address, and for more than a decade “Fiona Macleod” duped not only the general public but such literary luminaries as William Butler Yeats and, in America, E. C. Stedman. and “Fiona Macleod” Sharp wrote “I feel another self within me now more than ever; it is as if I were possessed by a spirit who must speak out”. This three-volume collec� on brings together Sharp’s own correspondence – a fascina� ng trove in its own right, by a Victorian man of le� ers who was on in� mate terms with writers including Dante Gabriel Rosse� , Walter Pater, and George Meredith – and the Fiona Macleod le� ers, which bring to life Sharp’s intriguing “second self”. -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

Baudelaire and the Rival of Nature: the Conflict Between Art and Nature in French Landscape Painting

BAUDELAIRE AND THE RIVAL OF NATURE: THE CONFLICT BETWEEN ART AND NATURE IN FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING _______________________________________________________________ A Thesis Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board _______________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS _______________________________________________________________ By Juliette Pegram January 2012 _______________________ Dr. Therese Dolan, Thesis Advisor, Department of Art History Tyler School of Art, Temple University ABSTRACT The rise of landscape painting as a dominant genre in nineteenth century France was closely tied to the ongoing debate between Art and Nature. This conflict permeates the writings of poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire. While Baudelaire scholarship has maintained the idea of the poet as a strict anti-naturalist and proponent of the artificial, this paper offers a revision of Baudelaire‟s relation to nature through a close reading across his critical and poetic texts. The Salon reviews of 1845, 1846 and 1859, as well as Baudelaire‟s Journaux Intimes, Les Paradis Artificiels and two poems that deal directly with the subject of landscape, are examined. The aim of this essay is to provoke new insights into the poet‟s complex attitudes toward nature and the art of landscape painting in France during the middle years of the nineteenth century. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to Dr. Therese Dolan for guiding me back to the subject and writings of Charles Baudelaire. Her patience and words of encouragement about the writing process were invaluable, and I am fortunate to have had the opportunity for such a wonderful writer to edit and review my work. I would like to thank Dr. -

Copyright by Deborah Helen Garfinkle 2003

Copyright by Deborah Helen Garfinkle 2003 The Dissertation Committee for Deborah Helen Garfinkle Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Bridging East and West: Czech Surrealism’s Interwar Experiment Committee: _____________________________________ Hana Pichova, Supervisor _____________________________________ Seth Wolitz _____________________________________ Keith Livers _____________________________________ Christopher Long _____________________________________ Richard Shiff _____________________________________ Maria Banerjee Bridging East and West: Czech Surrealism’s Interwar Experiment by Deborah Helen Garfinkle, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2003 For my parents whose dialectical union made this work possible ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express heartfelt thanks to my advisor Hana Pichova from the University of Texas at Austin for her invaluable advice and support during the course of my writing process. I am also indebted to Jiří Brabec from Charles University in Prague whose vast knowledge of Czech Surrealism and extensive personal library provided me with the framework for this study and the materials to accomplish the task. I would also like to thank my generous benefactors: The Texas Chair in Czech Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, The Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin, The Fulbright Commission and the American Council of Learned Societies without whom I would not have had the financial wherewithal to see this project to its conclusion. And, finally, I am indebted most of all to Maria Němcová Banerjee of Smith College whose intelligence, insight, generosity as a reader and unflagging faith in my ability made my effort much more than an exercise in scholarship; Maria, working with you was a true joy. -

PDF the Migration of Literary Ideas: the Problem of Romanian Symbolism

The Migration of Literary Ideas: The Problem of Romanian Symbolism Cosmina Andreea Roșu ABSTRACT: The migration of symbolists’ ideas in Romanian literary field during the 1900’s occurs mostly due to poets. One of the symbolist poets influenced by the French literature (the core of the Symbolism) and its representatives is Dimitrie Anghel. He manages symbols throughout his entire writings, both in poetry and in prose, as a masterpiece. His vivid imagination and fantasy reinterpret symbols from a specific Romanian point of view. His approach of symbolist ideas emerges from his translations from the French authors but also from his original writings, since he creates a new attempt to penetrate another sequence of the consciousness. Dimitrie Anghel learns the new poetics during his years long staying in France. KEY WORDS: writing, ideas, prose poem, symbol, fantasy. A t the beginning of the twentieth century the Romanian literature was dominated by Eminescu and his epigones, and there were visible effects of Al. Macedonski’s efforts to impose a new poetry when Dimitrie Anghel left to Paris. Nicolae Iorga was trying to initiate a new nationalist movement, and D. Anghel was blamed for leaving and detaching himself from what was happening“ in the” country. But “he fought this idea in his texts making ironical remarks about those“The Landwho were” eagerly going away from native land ( Youth – „Tinereță“, Looking at a Terrestrial Sphere” – „Privind o sferă terestră“, a literary – „Pământul“). Babel tower He settled down for several years in Paris, which he called 140 . His work offers important facts about this The Migration of Literary Ideas: The Problem of Romanian Symbolism 141 Roșu: period. -

Nietzsche, Debussy, and the Shadow of Wagner

NIETZSCHE, DEBUSSY, AND THE SHADOW OF WAGNER A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tekla B. Babyak May 2014 ©2014 Tekla B. Babyak ii ABSTRACT NIETZSCHE, DEBUSSY, AND THE SHADOW OF WAGNER Tekla B. Babyak, Ph.D. Cornell University 2014 Debussy was an ardent nationalist who sought to purge all German (especially Wagnerian) stylistic features from his music. He claimed that he wanted his music to express his French identity. Much of his music, however, is saturated with markers of exoticism. My dissertation explores the relationship between his interest in musical exoticism and his anti-Wagnerian nationalism. I argue that he used exotic markers as a nationalistic reaction against Wagner. He perceived these markers as symbols of French identity. By the time that he started writing exotic music, in the 1890’s, exoticism was a deeply entrenched tradition in French musical culture. Many 19th-century French composers, including Felicien David, Bizet, Massenet, and Saint-Saëns, founded this tradition of musical exoticism and established a lexicon of exotic markers, such as modality, static harmonies, descending chromatic lines and pentatonicism. Through incorporating these markers into his musical style, Debussy gives his music a French nationalistic stamp. I argue that the German philosopher Nietzsche shaped Debussy’s nationalistic attitude toward musical exoticism. In 1888, Nietzsche asserted that Bizet’s musical exoticism was an effective antidote to Wagner. Nietzsche wrote that music should be “Mediterranized,” a dictum that became extremely famous in fin-de-siècle France. -

Paris and Havana: a Century of Mutual Influence

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2014 Paris and Havana: A Century of Mutual Influence Laila Pedro Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/264 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Paris and Havana : A Century of Mutual Influence by LAILA PEDRO A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in French in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 LAILA PEDRO All Rights Reserved i This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in French in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Mary Ann Caws 04/22/2014 Date Chair of Examining Committee Francesca Canadé Sautman 04/22/2014 Date Executive Officer Mary Ann Caws Oscar Montero Julia Przybos Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK ii Abstract PARIS AND HAVANA: A CENTURY OF MUTUAL INFLUENCE by Laila Pedro Adviser: Mary Ann Caws This dissertation employs an interdisciplinary approach to trace the history of exchange and influence between Cuban, French, and Francophone Caribbean artists in the twentieth century. I argue, first, that there is a unique and largely unexplored tradition of dialogue, collaboration, and mutual admiration between Cuban, French and Francophone artists; second, that a recurring and essential theme in these artworks is the representation of the human body; and third, that this relationship ought not to be understood within the confines of a single genre, but must be read as a series of dialogues that are both ekphrastic (that is, they rely on one art-form to describe another, as in paintings of poems), and multi-lingual. -

4. Wagner Prelude to Tristan Und Isolde (For Unit 6: Developing Musical Understanding)

4. Wagner Prelude to Tristan und Isolde (For Unit 6: Developing Musical Understanding) Background information and performance circumstances Richard Wagner (1813-1883) was the greatest exponent of mid-nineteenth-century German romanticism. Like some other leading nineteenth-century musicians, but unlike those from previous eras, he was never a professional instrumentalist or singer, but worked as a freelance composer and conductor. A genius of over-riding force and ambition, he created a new genre of ‘music drama’ and greatly expanded the expressive possibilities of tonal composition. His works divided musical opinion, and strongly influenced several generations of composers across Europe. Career Brought up in a family with wide and somewhat Bohemian artistic connections, Wagner was discouraged by his mother from studying music, and at first was drawn more to literature – a source of inspiration he shared with many other romantic composers. It was only at the age of 15 that he began a secret study of harmony, working from a German translation of Logier’s School of Thoroughbass. [A reprint of this book is available on the Internet - http://archive.org/details/logierscomprehen00logi. The approach to basic harmony, remarkably, is very much the same as we use today.] Eventually he took private composition lessons, completing four years of study in 1832. Meanwhile his impatience with formal training and his obsessive attention to what interested him led to a succession of disasters over his education in Leipzig, successively at St Nicholas’ School, St Thomas’ School (where Bach had been cantor), and the university. At the age of 15, Wagner had written a full-length tragedy, and in 1832 he wrote the libretto to his first opera. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Gustav Mahler, Alfred Roller, and the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk: Tristan and Affinities Between the Arts at the Vienna Court Opera Stephen Carlton Thursby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GUSTAV MAHLER, ALFRED ROLLER, AND THE WAGNERIAN GESAMTKUNSTWERK: TRISTAN AND AFFINITIES BETWEEN THE ARTS AT THE VIENNA COURT OPERA By STEPHEN CARLTON THURSBY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephen Carlton Thursby defended on April 3, 2009. _______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my wonderful wife Joanna, for whose patience and love I am eternally grateful. In memory of my grandfather, James C. Thursby (1926-2008). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of numerous people. My thanks go to the staff of the Austrian Theater Museum and Austrian National Library-Music Division, especially to Dr. Vana Greisenegger, curator of the visual materials in the Alfred Roller Archive of the Austrian Theater Museum. I would also like to thank the musicology faculty of the Florida State University College of Music for awarding me the Curtis Mayes Scholar Award, which funded my dissertation research in Vienna over two consecutive summers (2007- 2008). -

A History of English Literature MICHAEL ALEXANDER

A History of English Literature MICHAEL ALEXANDER [p. iv] © Michael Alexander 2000 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W 1 P 0LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2000 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 0-333-91397-3 hardcover ISBN 0-333-67226-7 paperback A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 O1 00 Typeset by Footnote Graphics, Warminster, Wilts Printed in Great Britain by Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham, Wilts [p. v] Contents Acknowledgements The harvest of literacy Preface Further reading Abbreviations 2 Middle English Literature: 1066-1500 Introduction The new writing Literary history Handwriting -

French and Francophone Studies 1

French and Francophone Studies 1 www.brown.edu/academics/french-studies/undergraduate/honors- French and Francophone program/). Concentration Requirements Studies A minimum of ten courses is required for the concentration in French and Francophone Studies. Concentrators must observe the following guidelines when planning their concentration. It is recommended that Chair course choices for each semester be discussed with the department’s Virginia A. Krause concentration advisor. The Department of French and Francophone Studies at Brown promotes At least four 1000-level courses offered in the Department of 4 an intensive engagement with the language, literature, and cultural and French and Francophone Studies critical traditions of the French-speaking world. The Department offers At least one course covering a pre-Revolutionary period 1 both the B.A. and the PhD in French and Francophone Studies. Courses (i.e., medieval, Renaissance, 17th or 18th century France) cover a wide diversity of topics, while placing a shared emphasis on such as: 1 language-specific study, critical writing skills, and the vital place of FREN 1000A Littérature et intertextualité: du Moyen-Age literature and art for intellectual inquiry. Undergraduate course offerings jusqu'à la fin du XVIIème s are designed for students at all levels: those beginning French at Brown, FREN 1000B Littérature et culture: Chevaliers, those continuing their study of language and those undertaking advanced sorcières, philosophes, et poètes research in French and Francophone literature, culture and thought. Undergraduate concentrators and non-concentrators alike are encouraged FREN 1030A L'univers de la Renaissance: XVe et XVIe to avail of study abroad opportunities in their junior year, through Brown- siècles sponsored and Brown-approved programs in France or in another FREN 1030B The French Renaissance: The Birth of Francophone country. -

Re-Translating Asian Poetry

Comparative Critical Studies 17.2 (2020): 183–203 Edinburgh University Press DOI: 10.3366/ccs.2020.0358 C Francesca Orsini. The online version of this article is published as Open Access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial Licence (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction provided the original work is cited. For commercial re-use, please refer to our website at: www.euppublishing.com/customer-services/authors/permissions. www.euppublishing.com/ccs From Eastern Love to Eastern Song: Re-translating Asian Poetry FRANCESCA ORSINI Abstract: This essay explores the loop of translations and re-translations of ‘Eastern poetry’ from Asia into Europe and back into (South) Asia at the hands of ‘Oriental translators’, translators of poetry who typically used existing translations as their original texts for their ambitious and voluminous enterprises. If ‘Eastern’ stood in all cases for a kind of exotic (in the etymological sense of ‘from the outside’) poetic exploration, for Adolphe Thalasso in French and E. Powys Mathers in English, Eastern love poetry could shade into prurient ethno-eroticism. For the Urdu poet and translator Miraji, instead, what counted in Eastern poetry was oral, rhythmic and visual richness – song. Keywords: Orientalism, poetry, translation, lyric In the century and a half between William Jones’ Poems Consisting Chiefly of Translations from the Asiatick Languages in 1772 and Ezra Pound’s 1915 ‘removal’ of ‘the crust of dead English’ from his ‘translation’ of Chinese poetry in Cathay, Oriental or Eastern poetry translations, particularly of classical poetry, became a mainstay of European print culture at all levels, as the contributions to this special issue show (particularly Burney, Italia, and Bubb).1 In Britain, the culture of translation was profoundly changed by this expansion of translation beyond the tradition of English or European literature.