The Silent Service Understanding the Covert World of Canadian Submarine Operations During the Cold War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'A Little Light on What's Going On!'

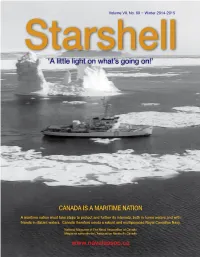

Volume VII, No. 69 ~ Winter 2014-2015 Starshell ‘A little light on what’s going on!’ CANADA IS A MARITIME NATION A maritime nation must take steps to protect and further its interests, both in home waters and with friends in distant waters. Canada therefore needs a robust and multipurpose Royal Canadian Navy. National Magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada www.navalassoc.ca On our cover… To date, the Royal Canadian Navy’s only purpose-built, ice-capable Arctic Patrol Vessel, HMCS Labrador, commissioned into the Royal Canadian Navy July 8th, 1954, ‘poses’ in her frozen natural element, date unknown. She was a state-of-the- Starshell art diesel electric icebreaker similar in design to the US Coast Guard’s Wind-class ISSN-1191-1166 icebreakers, however, was modified to include a suite of scientific instruments so it could serve as an exploration vessel rather than a warship like the American Coast National magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Guard vessels. She was the first ship to circumnavigate North America when, in Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada 1954, she transited the Northwest Passage and returned to Halifax through the Panama Canal. When DND decided to reduce spending by cancelling the Arctic patrols, Labrador was transferred to the Department of Transport becoming the www.navalassoc.ca CGSS Labrador until being paid off and sold for scrap in 1987. Royal Canadian Navy photo/University of Calgary PATRON • HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh HONORARY PRESIDENT • H. R. (Harry) Steele In this edition… PRESIDENT • Jim Carruthers, [email protected] NAC Conference – Canada’s Third Ocean 3 PAST PRESIDENT • Ken Summers, [email protected] The Editor’s Desk 4 TREASURER • King Wan, [email protected] The Bridge 4 The Front Desk 6 NAVAL AFFAIRS • Daniel Sing, [email protected] NAC Regalia Sales 6 HISTORY & HERITAGE • Dr. -

Maritime Engineering Journal No

National Défense Defence nationale Maritime Engineering 68 Journal Since 1982 Canada’s Naval Technical Forum Fall 2011 Manoeuvring HMCS OnOndaga into position for permanent display at rimouski’s Site maritime historique de la Pointe-au-Père took a bit more effort than anyone imagined – Lt(N) Peter Sargeant explains Also in this Issue: CNTHA • The Naval Materiel Management System – News Inside! a NaMMS update • More Mar Eng QL6 service papers from our navy technical branch NCMs Model Power! Marine model maker Tom Power plies his exacting craft at Halifax’s Maritime Museum of the Atlantic. Photo by Brian McCullough by Photo – Page 22 – maritime engineering journal no. 68 – Fall 2011 Maritime Engineering 68 (Established 1982) Journal Fall 2011 Commodore’s Corner Complex naval materiel program calls for increased focus from all of us, by Commodore Patrick T. Finn, OMM, CD, Director General Maritime Director General Equipment Program Management .................................................................................................... 2 Maritime Equipment Program Management Forum Commodore Patrick T. Finn Proposed Solutions For Vibration Analyst Training – A Mar Eng QL6 Course OMM, CD Technical Service Paper Adaptation, by PO2 Patrick M. Lavigne ............................................. 3 Feature artiCles NaMMS Review and Update – Revised Naval Materiel Management Senior Editor System policy document reflects current best practices, Capt(N) Marcel Hallé by LCdr Stéphane Ricard and Mr. Glenn Murphy ......................................................................... -

Okanagan Nation E-News

S Y I L X OKANAGAN NATION E-NEWS April 2010 Okanagan Nation Jr. Girls Bring Home Provincial Championship Table of Contents HMCS Okanagan 2 Syilx Youth Unity Run 3 Browns Creek 4 Update Child & Family 6 NRLUT Update FN Leaders 7 Denounce Fed Funding Cuts Health Hub 8 Columbia River 9 93,000 Sockeye 10 Released Sturgeon 11 Gathering AA Roundup 12 Photo: Team Mng Lisa Reid, Ashley McGinnis, Dina Brown, Jasmine Reid, Janessa Lambert, Coach Peter Waardenburg, Erica Swan, Jade Waardenburg, Nicola Terbasket, Coach Amanda Montgomery, Kirsten Lindley, Front: Jade Sargent Family 13 Missing Courtney Louie Intervention The Syilx, Okanagan Nation, Jr Girls basketball ball it was stolen by Reid, passed to Sargent and Society Conf ONA Bursary 14 team brought home the Championship and she did a lay in to win the game. Most Sportsmanlike Team after playing 8 R Native Voice 15 “Okanagan girls were full value for the win, University Camp 16 games in Prince Rupert during Spring Break. hard working and all the class in the world.” Fish Lake 17 The final four games were all nail biters, said said Kitimat coach Keith Nyce. What’s Reid; the gym was vibrating with the fans from Happening 18 Other awards included MVP, Jade Toll Free all the villages cheering on their nations. Waardenburg, Best Defense and All Star In the final game against Kitimat there was only 1-866-662-9609 Jasmine Reid, and All Star Ashley McGinnis 9 seconds left, Okanagan down by 2, when Waardenburg drew the foal that would take The Okanagan Nation will host the 2011 Jr All her to the free throw line. -

100 Years of Submarines in the RCN!

Starshell ‘A little light on what’s going on!’ Volume VII, No. 65 ~ Winter 2013-14 Public Archives of Canada 100 years of submarines in the RCN! National Magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada www.navalassoc.ca Please help us put printing and postage costs to more efficient use by opting not to receive a printed copy of Starshell, choosing instead to read the FULL COLOUR PDF e-version posted on our web site at http:www.nava- Winter 2013-14 lassoc.ca/starshell When each issue is posted, a notice will | Starshell be sent to all Branch Presidents asking them to notify their ISSN 1191-1166 members accordingly. You will also find back issues posted there. To opt out of the printed copy in favour of reading National magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Starshell the e-Starshell version on our website, please contact the Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada Executive Director at [email protected] today. Thanks! www.navalassoc.ca PATRON • HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh OUR COVER RCN SUBMARINE CENTENNIAL HONORARY PRESIDENT • H. R. (Harry) Steele The two RCN H-Class submarines CH14 and CH15 dressed overall, ca. 1920-22. Built in the US, they were offered to the • RCN by the Admiralty as they were surplus to British needs. PRESIDENT Jim Carruthers, [email protected] See: “100 Years of Submarines in the RCN” beginning on page 4. PAST PRESIDENT • Ken Summers, [email protected] TREASURER • Derek Greer, [email protected] IN THIS EDITION BOARD MEMBERS • Branch Presidents NAVAL AFFAIRS • Richard Archer, [email protected] 4 100 Years of Submarines in the RCN HISTORY & HERITAGE • Dr. -

Lead and Line April

April 2015 volume 3 0 , i s s u e N o . 4 LEAD AND LINE newsletter of the naval Association of canada-vancouver island Buzzed by Russians...again At sea with Victoria Monsters be here Another cocaine bust Page 2 Page 3 Page 9 Page 14 HMCS Victoria Update... Page 3 Speaker: Captain Bill Noon NAC-VI Topic: Update on the Franklin Expedition 27 Apr Cost will be $25 per person. Luncheon Guests - spouses, friends, family are most welcome Please contact Bud Rocheleau [email protected] or Lunch at the Fireside Grill at 1130 for 1215 250-386-3209 prior to noon on Thursday 19 Mar. 4509 West Saanich Road, Royal Oak, Saanich. NPlease advise of any allergies or food sensitivities Ac NACVI • PO box 5221, Victoria BC • Canada V8R 6N4 • www.noavi.ca • Page 1 April 2015 volume 30 , i s s u e N o . 4 NAC-VI LEAD AND LINE Don’t be so wet! There has been a great kerfuffle on Parliament Hill, and in the press, about the possibility that HMCS Fredericton might have been confronted by a Russian warship and buzzed by Russian fighter jets. Not so says NATO, stating that any Russian vessels were on the horizon and the closest any plane got was 69 kilometers. (Our MND says it was within 500 ft!) An SU-24 Fencer circled HMCS Toronto, during NATO op- And so what if they did? It would hardly be surprising, if erations in the Black Sea last September. in a period of some tension (remember the Ukraine) that a Russian might be interested in scoping out the competition And you can’t tell me that the Americans (who were with us or that we might be interested in doing the same in return. -

'A Little Light on What's Going On!'

Volume VII, No. 72, Autumn 2015 Starshell ‘A little light on what’s going on!’ CANADA IS A MARITIME NATION A maritime nation must take steps to protect and further its interests, both in home waters and with friends in distant waters. Canada therefore needs a robust and multipurpose Royal Canadian Navy. National Magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada www.navalassoc.ca On our cover… The Kingston-class Maritime Coastal Defence Vessel (MCDV) HMCS Whitehorse conducts maneuverability exercises off the west coast. NAVAL ASSOCIATION OF CANADA ASSOCIATION NAVALE DU CANADA (See: “One Navy and the Naval Reserve” beginning on page 9.) Royal Canadian Navy photo. Starshell ISSN-1191-1166 In this edition… National magazine of the Naval Association of Canada Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada From the Editor 4 www.navalassoc.ca From the Front Desk 4 PATRON • HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh NAC Regalia Sales 5 HONORARY PRESIDENT • H. R. (Harry) Steele From the Bridge 6 PRESIDENT • Jim Carruthers, [email protected] Maritime Affairs: “Another Step Forward” 8 PAST PRESIDENT • Ken Summers, [email protected] One Navy and Naval Reserve 9 TREASURER • King Wan, [email protected] NORPLOY ‘74 12 NAVAL AFFAIRS • Daniel Sing, [email protected] Mail Call 18 HISTORY & HERITAGE • Dr. Alec Douglas, [email protected] The Briefing Room 18 HONORARY COUNSEL • Donald Grant, [email protected] Schober’s Quiz #69 20 ARCHIVIST • Fred Herrndorf, [email protected] This Will Have to Do – Part 9 – RAdm Welland’s Memoirs 20 AUSN LIAISON • Fred F. -

HMCS Chicoutimi

Submariners Association of Canada-West Newsletter Angles & Dangles HMCS Chicoutimi www.saocwest.ca SAOC-WEST www .saocwest.ca Fall 2020 Page 2 IN THIS ISSUE: Page 1 Cover HMCS Chicoutimi Page 2 Index President Page 3 From the Bridge Report Wade Berglund 778-425-2936 Page 4 HMCS Chicoutimi [email protected] Page 5-6 RCN Submariners Receive Metals Page 7 -8 China’s Submarines Can Now Launch A Nuclear War Against America Page 9-10 Regan Carrier Strike Group Vice-President Patrick Hunt Page 11-12 US, Japan, Australia Team Up 250-213-1358 [email protected] Page 13-14 China’s Strategic Interest in the Artic Page 15 Royal Navy Officer ‘Sent Home” Page 16-17 Watch a Drone Supply Secretary Page 18-20 Cdn Navy Enters New Era Warship Lloyd Barnes 250-658-4746 Page 21-23 Are Chinese Submarines Coming [email protected] Page 24-25 Lithium-ion Batteries Page 26 A Submariner’s Perspective Page 27-28 Iran’s New Submarine Debuts Treasurer & Membership Page 29 Media-Books Chris Parkes 250-658-2249 Page 30 VJ Day– Japan 1945 Chris [email protected] Page 31 Priest Sent To Prison Page 32 Award Presentation Page 33 Eternal Patrol Page 34 Below Deck’s & Lest We Forget Angles & Dangles Newsletter Editor Valerie Brauschweig [email protected] The SAOC-W newsletter is produced with acknowledgement & appreciation to the authors of articles, writers and photographers, Cover Photo: stories submitted and photos sourced . HMCS Chicoutimi Opinions expressed are not necessarily those of SAOC-W. Fall 2020 SAOC-WEST Page 3 review the Constitution and Bylaws, and a decision as The Voice Pipe to holding member meetings was made. -

1997-1998 Estimates

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. National Defence Performance Report ESTIMATES For the period ending March 31, 1998 Improved Reporting to Parliament Pilot Document The Estimates of the Government of Canada are structured in several parts. Beginning with an overview of total government spending in Part I, the documents become increasingly more specific. -

Part I - Updated Estimate Of

Part I - Updated Estimate of Fair Market Value of the S.S. Keewatin in September 2018 05 October 2018 Part I INDEX PART I S.S. KEEWATIN – ESTIMATE OF FAIR MARKET VALUE SEPTEMBER 2018 SCHEDULE A – UPDATED MUSEUM SHIPS SCHEDULE B – UPDATED COMPASS MARITIME SERVICES DESKTOP VALUATION CERTIFICATE SCHEDULE C – UPDATED VALUATION REPORT ON MACHINERY, EQUIPMENT AND RELATED ASSETS SCHEDULE D – LETTER FROM BELLEHOLME MANAGEMENT INC. PART II S.S. KEEWATIN – ESTIMATE OF FAIR MARKET VALUE NOVEMBER 2017 SCHEDULE 1 – SHIPS LAUNCHED IN 1907 SCHEDULE 2 – MUSEUM SHIPS APPENDIX 1 – JUSTIFICATION FOR OUTSTANDING SIGNIFICANCE & NATIONAL IMPORTANCE OF S.S. KEEWATIN 1907 APPENDIX 2 – THE NORTH AMERICAN MARINE, INC. REPORT OF INSPECTION APPENDIX 3 – COMPASS MARITIME SERVICES INDEPENDENT VALUATION REPORT APPENDIX 4 – CULTURAL PERSONAL PROPERTY VALUATION REPORT APPENDIX 5 – BELLEHOME MANAGEMENT INC. 5 October 2018 The RJ and Diane Peterson Keewatin Foundation 311 Talbot Street PO Box 189 Port McNicoll, ON L0K 1R0 Ladies & Gentlemen We are pleased to enclose an Updated Valuation Report, setting out, at September 2018, our Estimate of Fair Market Value of the Museum Ship S.S. Keewatin, which its owner, Skyline (Port McNicoll) Development Inc., intends to donate to the RJ and Diane Peterson Keewatin Foundation (the “Foundation”). It is prepared to accompany an application by the Foundation for the Canadian Cultural Property Export Review Board. This Updated Valuation Report, for the reasons set out in it, estimates the Fair Market Value of a proposed donation of the S.S. Keewatin to the Foundation at FORTY-EIGHT MILLION FOUR HUNDRED AND SEVENTY-FIVE THOUSAND DOLLARS ($48,475,000) and the effective date is the date of this Report. -

Royal Canadian Navy Aircraft Carrier Her Majesty’S Canadian Ship Bonaventure – CVL 22 21 January 1957 – 3 July 1970

Royal Canadian Navy Aircraft Carrier Her Majesty’s Canadian Ship Bonaventure – CVL 22 21 January 1957 – 3 July 1970 Introduction In April 1962, the Canadian Government approved the acquisition of an aircraft carrier to replace Her Majesty’s Canadian Ship (HMCS) Magnificent (CVL 21), which had been on loan and was to be returned to the Royal Navy (RN). At the same time, a decision was taken to purchase and modernize an unfinished Second World War era aircraft carrier. The Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) set up a negotiating team to deal with the British Government and the Royal Navy. The RN argued that the contract to purchase the new carrier required that HMCS Magnificent be brought up to the latest “alterations and additions” (A&As) for her class before her return to the RN. These alterations were to include, among other modifications, an angled and strengthened deck. The RCN’s case was that these were modernizations and not A&As. Furthermore, the carrier being offered for purchase was being bought “as is”, therefore the RN must accept the return of HMCS Magnificent in an “as is” state. The Royal Navy was won over to the Canadian’s point of view and the negotiations were soon completed. A new project office for the Principal Royal Canadian Navy Technical Representative was established at Belfast, Northern Ireland, where the partially completed Majestic class, Light Fleet aircraft carrier, the ex-Her Majesty’s Ship (HMS) Powerful (R 95) was laying. Specifications With a length overall of 215 meters (705 ft) and a beam at the water line of 24 meters (79 ft), HMS Powerful was only slightly larger than HMCS Magnificent. -

Ball Hockey on the Jetty

173043 Monday, August 26, 2019 Volume 53, Issue 17 www.tridentnewspaper.com Ball hockey on the jetty Sailors from HMCS Halifax made time for a game of ball hockey during a recent port visit to Lisbon, Portugal. The ship is currently deployed to Op REASSUR- ANCE as the flagship of SNMG2. CPL BRADEN TRUDEAU, FIS New exhibit at Naval National Peacekeepers' HMCS Goose Bay back Highlights from Op Museum Pg. 3 Day ceremony Pg. 7 from Caribbean Pg. 10 REASSURANCE Pg. 14 We have all your shopping needs. VISIT WINDSOR PARK Now Open SUNDAYS 1200 - 1700 CANEX.ca 173039 2 TRIDENT NEWS AUGUST 26, 2019 Vice Admiral’s flag hoist signal S I assume command from my After all, you, today’s sailors, are an Our status as a long-time shipmate, Vice impressive lot to command: inspired Forbes-recognized best Admiral Ron Lloyd, I am equally by a rich history and the bright Canadian employer humbled and honoured to future that the ongoing largest peace- depends upon it. followA in the wake of the admirals that time fleet recapitalization in our history Our shipmates preceded me upon being chosen as your ensures. depend upon it. 36th commander. You are equal parts warrior and dip- Those whom we serve lomat as you inspire with the depth depend upon it. and breadth of your successes alongside As we look to the partners and allies at home and around future, shipmates, the the globe; as you routinely combat cri- “how” behind what ses - man-made or naturally occurring; as we do will continue to you ensure that you remain ready to help, matter enormously. -

Great Lakes Museums

GreatGreat LakesLakes MuseumsMuseums Around the Great Lakes, we are blessed with a wide variety of museums devoted to preserving and caring for our historical, scientific, artistic and cultural heritage. From large, nationally sponsored institutions to small community museums, there is a wealth of information and artifacts that can truly capture your imagination. As you cruise these waters, take time to investigate these gems. (And they make a great trip by car too!). This list is organized by lake. It is not exhaustive. There are many more fine community museums in the towns and villages that dot the coastline of the Great Lakes. If you see one that you think should be added, by all means send me a note. I will be happy to update this list. For each entry, I have included only its name, the relevant port and a website if they have one. Where useful, I have also included a brief note about each. Enjoy! Michael Leahy, Publisher LAKE ONTARIO HMCS Haida Hanilton, ON hmcshaida.com HMCS Haida is the last surviving Tribal Class destroyer from WWII. She sank the most tonnage of any Canadian warship in WWII. During service in the Korean War, she joined the famous "Trainbusters Club" - that small group of daring warships who closed close enough to the enemy coastline to shell and destroy individual freight trains. Now a National Historic Site, she is open for tours. Marine Museum of the Great Lakes at Kingston Kingston, ON www.marmuseum.ca The Marine Museum of the Great Lakes in Kingston was founded in 1975.