Hamilton's Boathouse Community and the Re-Creation of Recreation on Burlington Bay Nancy B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning Adventures Field Trip Planner 2012-2013

LEARNING ADVENTURES FIELD TRIP PLANNER 2012-2013 Real People. Real Stories. Real Adventure! Educators can request additional copies of our Learning Adventures Field Trip Planner by calling Brenda Branch, Marketing and Promotions at 905-546-2424 ext. 7527. To download a copy, please visit www.hamilton.ca/museums CURRICULUM-BASED EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS AT-A-GLANCE Grade(s) Subject(s) Curriculum Strand(s) Curriculum Topic(s) Site Program Title Page # Outreach Most lower level programs can be adapted for delivery to the Kindergarten level. JK/SK Specific programs are outlined throughout this publication. JK/SK Language, Mathematics, The Arts NA NA Dundurn Castle Jacob’s Ladder 1 Language; Mathematics; Science; Personal JK/SK and Social Development; The Arts; Health and NA NA Children’s Museum Learning Through Play 12 Physical Activity Language; Science and Technology; Personal JK/SK and Social Development; Health and Physical NA NA Farmers’ Market Beautiful Beans 20 Activity JK/SK Mathematics; Social Studies; The Arts NA NA Whitehern Time for Tea 4 JK/SK Mathematics; The Arts NA NA Whitehern Teddy Bears’ Picnic - NEW! 4 Personal and Social Development; Language; JK/SK NA NA Battlefield House Many Hands Make Light Work 6 The Arts; Science Personal and Social Development; Language; Holiday Traditions with the Gage JK/SK NA NA Battlefield House 6 The Arts; Science Family JK/SK The Arts NA NA Children’s Museum Acting Out 12 Healthy Eating; Personal Safety and Injury Communicating Messages - Media 1 Language; Health and Physical Education Media -

Hamilton Ontario Map Pdf

Hamilton ontario map pdf Continue For a city in Northumberland County, see Hamilton, Ontario (city). City of Ontario, CanadaHamiltonCity (single-layer)HamiltonCounter clockwise from top: A view of the center of Hamilton from Sam Lawrence Park, Hamilton Town Hall, bayfront park harbour front trail, historic art deco and gothic complex Revival building Pigott, Webster's Falls, Dundurn Castle FlagCoat of armsNicknames: The Ambitious City, The Electric City, The Hammer, Steeltown[1][2][3]Motto(s): Together Aspire – Achieve TogetherLocation in the Province of Ontario, CanadaHamiltonLocation of Hamilton in southern OntarioCoordinati: 43°15′24N 7 9°52′09W / 43.25667°N 79.86917°W / 43.25667; -79.86917Coordinates: 43°15′24N 79°52′09W / 43.25667°N 79.86917°W / 43.25667; -79.86917CountryCanadaProvince Ontario Inc.ratedJune 9, 1846[4]Named forGeorge HamiltonGovernment • MayorFred Eisenberger • Hamilton City Council • Bob Bratina (L)Matthew Green (NDP)Scott Duvall (NDP)David Sweet (C)Filomena Tassi (L) • List of Deputies Andrea Horwath (NDP)Paul Miller (NDP)Sandy Shaw (NDP)Donna Skelly (PC)Monique Area Taylor (NDP) [5] • City (single-layer)1,138.11 km2 (439.43 m2) • Land plot1,117.11 km2 (431.32 m2) • Water21 km2 (8 square meters) • Urban351.67 km2 (13 5,5,5,5,11,1199) 78 m²) • Metro1,371.76 km2 (529.64 m² mi)Highest altitude324 m (1,063 ft)Lowest altitude75 m (246 ft)Population (2016) • City (single layer)536,917 (10th) • Density480.6/km2 (1,245/sq mi) • Urban[6]693.645 • Metro763,445 (9th)Demonym(s)HamiltonianTime zoneUTC−5 (EST) • Summer (DST)UTC 4 (EDT)Sorting Area L8E to L8W , L9A to L9C, L9G to L9H, L9KArea codes226, 289, 519, 365 and 905Highways Queen Elizabeth Way Highway 6 Highway 20 Highway 403Websitewww.hamilton.ca Hamilton is a port city in the Canadian province of Ontario. -

Appendix 23: Environmental Class Assessment Appendix 23

Appendix 23: Environmental Class Assessment Appendix 23 Figure 18: Municipal Class Environmental Assessment Planning and Design Process, shows the workflow necessary to meet the Municipal Class Environmental Assessment requirements that are applicable to this Pedestrian Mobility Plan study. The overall approach to the Pedestrian Mobility Plan reflects the following key principles of successful Environmental Assessment planning1: • “Consultation with affected parties early in and throughout the process” • “Consideration of a reasonable range of alternatives” • “Identification and consideration of the effects of each alternative on all aspects of the environment” • “Systematic evaluation of alternatives in terms of their advantages and disadvantages to determine their net environmental effects” • “Provision of clear and complete documentation of the planning process followed, to allow 'traceability' of decision‐making with respect to the project”. Phase 1 identifies the problems and opportunities associated with the City's pedestrian mobility network. Phase 2 develops alternative solutions to address the identified problems and opportunities, with consideration for the existing environment and input from the public and regulatory agencies. The workflow incorporates one discretionary and two mandatory points of contact with the public. The public are invited to participate and submit comments on this study through various mediums, including on‐line mapping, surveys, and Public Information Centres. In the end, a Plan document is prepared for a minimum 30‐day public review period. A Notice of Study Completion will be advertised in the Hamilton Spectator and local community newspapers to announce the 30‐day review period. Part II of the Environmental Assessment Act refers to the Ministry of Environment’s review and approval for individual environmental assessments. -

THE ARTERY News from the Britannia Art Gallery January 1, 2017 Vol

THE ARTERY News from the Britannia Art Gallery January 1, 2017 Vol. 44 Issue 96 While the Artery is providing this newsletter as a courtesy service, every effort is made to ensure that information listed below is timely and accurate. However we are unable to guarantee the accuracy of information and functioning of all links. INDEX # ON AT THE GALLERY: Exhibition Laurel Swenson Exploding Bouquets & Grey Studies 1 Deconstructivism Edzy Edzed Opening Reception: Wednesday, Jan 4, 6:30 pm ARTIST TALK Deconstructivism – Edzed. Jan 18, 7 pm 2 EVENTS AROUND TOWN EVENTS 3/4 EXHIBITIONS 5-16 THEATRE 17-21 WORKSHOPS 22-26 CALLS FOR SUBMISSIONS LOCAL EXHIBITIONS 27 GRANTS 28 JOB CALL 29-32 MISCELLANEOUS 33 CALLS FOR SUBMISSIONS NATIONAL AWARDS 34 COMPETITION 35/36 EXHIBITIONS 37-53 FAIR 54 FESTIVAL 55-59 JOB CALL 60-73 CALL FOR PARTICPATION 74 PERFORMANCE & ARTWORKS 75 CONFERENCE 76 PUBLICATION 77 PUBLIC ART 78-80 RESIDENCY 81-85 SYMPOSIUM 86 CALLS FOR SUBMISSIONS INTERNATIONAL WEBSITE 87 BY COUNTRY AMAZON RESIDENCY 88 BELGIUM FESTIVAL 89 CANADA RESIDENCY 90 GERMANY RESIDENCY 91 MEXICO RESIDENCY 92 SCOTLAND RESIDENCY 93 SWEDEN RESIDENCY 94 UK RESIDENCY 95 USA COMPETITION 96 EXHIBITION 97 RESIDENCY 98 BRITANNIA ART GALLERY: SUBMISSIONS TO THE ARTERY E-NEWSLETTER 99 VOLUNTEER RECOGNITION 100 GALLERY CONTACT INFORMATION 101 ON AT BRITANNIA ART GALLERY 1 EXHIBITIONS: January 4 -27 Exploding Bouqets Series & Studies in Grey - Laurel Swenson Decontructivism through gouged Plywood Painting – Edzy Edzed Opening Reception: Wed. January 4th., 6:30 – 8:30 pm All gallery events are free to the public 2 ARTIST TALK: Edzey Edzed - Decontructivism Wednesday, January 18, 7pm EVENTS AROUND TOWN 3 EVENTS: LORI SOKOLUK - NEW WORK ON EXHIBIT December 28, 2016 - January 28, 2017 Vancouver East Cultural Centre 1895 Venables Street (at Victoria) Gallery Hours: Mon-Sat noon-4pm and 1 hour prior to performances 4 EVENTS: ON @ SFU WOODWARDS Gwynne Dyer: The Climate Horizon March 22, 2017, 7:00 PM Tickets: $25 Djavad Mowafaghian Cinema, Goldcorp Centre for the Arts, 149 W. -

Landscape Architect Quarterly Features CSLA Awards OALA Awards Round Table Winning Trends Summer 2009 Issue 06

06 Landscape Architect Quarterly 10/ Features CSLA Awards OALA Awards 16/ Round Table Winning Trends Summer 2009 Issue 06 P u b l i c a t i o n # 4 0 0 2 6 1 0 6 Messages .06 03 Letters to the Editor President’s Message I particularly enjoyed the issue on trees [ Ground 05]. Like the previous I am honoured to hold the prestigious office of OALA President issues, Ground includes articles that are theoretical and challenging and look forward to serving the membership. The president’s job while providing practical information that is relevant to our practice is typically a busy one; however, I am comforted by the knowledge in Ontario. that I am surrounded by extremely talented and dedicated coun - cillors who are there to help. On behalf of Council, I extend a One concern I have is that the images don't seem to be as crisp as heartfelt thanks to Arnis Budrevics for his successful tenure as they could or should be. Since our profession is quite visually orient - president for the past two years. ed, can the images in Ground be printed with greater clarity without compromising any sustainability objectives you might have? The OALA held its 41st Annual General Meeting on May 6, 2009 at the Grand Hotel in Toronto. This was another successful event Finally, congratulations on the CSLA award that Ground received and included presentations of the OALA Awards and the CSLA this year. The award is well-deserved acknowledgement of your Regional Awards of Excellence that are featured in this issue of great work and recognizes the passion and commitment of the Ground . -

The Life Writings of Mary Baker Mcquesten, Victorian Matriarch' and Armstrong, 'Seven Eggs Today: the Diaries of Mary Armstrong, 1859 and 1869'

H-Canada King on Anderson, 'The Life Writings of Mary Baker McQuesten, Victorian Matriarch' and Armstrong, 'Seven Eggs Today: The Diaries of Mary Armstrong, 1859 and 1869' Review published on Monday, November 1, 2004 Mary J. Anderson, ed. The Life Writings of Mary Baker McQuesten, Victorian Matriarch. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier Press, 2004. xxii + 337 pp. $55.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-88920-437-9.Jackson W. Armstrong, ed. Seven Eggs Today: The Diaries of Mary Armstrong, 1859 and 1869. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2004. xvi + 228 pp. $49.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-88920-440-9. Reviewed by Alyson E. King (Department of History, Trent University)Published on H-Canada (November, 2004) A Tale of Two Marys: Women's Lives in Diaries and Letters These two books, Seven Eggs Today: The Diaries of Mary Armstrong, 1859 and 1869 and The Life Writings of Mary Baker McQuesten, Victorian Matriarch, provide unique snapshots into the lives of two women in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Ontario, using diaries and letters. The two forms provide alternative ways of looking into the lives of individual women and, therefore, different types of information. On the one hand, Mary Wickson Armstrong was decidedly middle class. Her diaries were written without the expectation that they would be read by anyone other than herself. Mary Baker McQuesten, on the other hand, was considerably more well-to-do, at least until her husband's death. Her letters were written and purposefully saved in the expectation that they would be read at least by other members of the family, and often with the forethought that the family would be restored to a prominent place in society. -

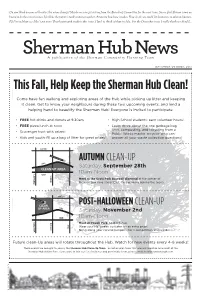

This Fall, Help Keep the Sherman Hub Clean!

Do you think anyone will notice the name change? Maybe we can get a story from the Branding Committee for the next issue. Soooo glad Shiona came on board to do the event listings. I feel like the paper is really coming together. Amazing how long it takes. Now if only we could find someone to take on finance. PS I’m sad that we didn’t get more Thanksgivingish stuff in this issue. Hard to think of that in July. For the December issue I really think we should… A publication of the Sherman Community Planning Team SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER, 2013 This Fall, Help Keep the Sherman Hub Clean! Come have fun walking and exploring areas of the Hub while picking up litter and keeping it clean. Get to know your neighbours during these two upcoming events, and lend a helping hand to beautify the Sherman Hub! Everyone is invited to participate. • FREE hot drinks and donuts at 9:30am • High School students: earn volunteer hours! • FREE pizza lunch at noon • Learn more about the one garbage bag limit, composting, and recycling from a • Scavenger hunt with prizes! Public Works master recycler who can • Kids and youth: fill up a bag of litter for great prizes! answer all your waste collection questions! AUTUMN CLEAN-UP Saturday, September 28th 10am-Noon Meet at the Scott Park baseball diamond at the corner of Melrose and King Street East. Free parking behind the arena. POST-HALLOWEEN CLEAN-UP Saturday, November 2nd 10am-Noon Meet at Powell Park, 53 Birch Ave. Wear your Halloween costume for an extra prize! Bring along your carved pumpkins for a competition afterwards! Future clean-Up areas will rotate throughout the Hub. -

Walter Gretzky – Lord Mayor of Brantford Tribute Bust the Project

Glenhyrst Art Gallery of Brant – Public Art Project Proposal Walter Gretzky – Lord Mayor of Brantford Tribute Bust Glenhyrst Art Gallery of Brant is a public regional art gallery in Brantford, Ontario that provides the region with six annual art exhibitions, over 40 events per year, a variety of art classes, workshops and camps for both adults and children, and a Permanent Collection with over 600 artworks. Glenhyrst is dedicated to engaging our local and regional communities with art and culture. As such, we propose a public art project that combines Brantford’s love of hockey while honouring our recently passed local hero, Walter Gretzky. Our focus on providing the community with public art in recent years fulfills our mandate to reframe the way that art and culture is accessed and encountered throughout the city, further expanding our responsibility as a public art gallery. The Project Glenhyrst was approached last year by the City of Brantford to facilitate the Call to Artists for the Walter Gretzky Portrait for the newly named Walter Gretzky Municipal Golf Course (previously the Northridge Municipal Golf Course). During that facilitation process, we took notice of one of the entries: a local sculptor named Robert Dey, who submitted a clay cast (to be bronzed) of Walter Gretzky as his submission. The submission was not chosen by the Jurors for the Portrait Call for Artists, but after the passing of Mr. Gretzky, we feel that creating a bust is a tremendous opportunity to honour him as Brantford’s only Lord Mayor. We have approached the artist and he is excited about the prospect of honouring Mr. -

Recommendation to Designate Under the Ontario Heritage Act Part

PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT CITY OF HAMILTON - RECOMMENDATION - DATE: February 1, 2002 File: Author: S. Barber (905) 643-1262 x. 204 REPORT TO: Mayor and Members Committee of the Whole FROM: Lee Ann Coveyduck General Manager Planning and Development Department SUBJECT: Recommendation to Designate under the Ontario Heritage Act, Part IV, the Property at 685 York Boulevard in the Former City of Hamilton, Known as the Rock Garden (PD02019) (Affects Ward 1) RECOMMENDATION: (a) That Council be advised that the request for Designation by the Royal Botanical Gardens of its Rock Garden at 685 York Boulevard as a property of historical and architectural value or interest pursuant to the provisions of Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act, 1990, be approved; and, (b) That Council be advised to direct Corporate Counsel to take appropriate action to designate under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act, 1990, as described in the attached Reasons for Designation (Appendix A). _____________________________ Lee Ann Coveyduck General Manager Planning and Development Department CORPORATE IMPLICATIONS: Not applicable. Recommendation to Designate under the Ontario Heritage Act, Part IV, the Property at 685 York Boulevard in the Former City of Hamilton, Known as the Rock Garden (PD02019)(Affects Ward 1) Page 2 BACKGROUND: The former Hamilton LACAC approved the eligibility for designation of the Rock Garden at its meeting held July 10, 2000 in response to a letter of request from the President of the Royal Botanical Garden's (RBG) Board of Directors. The research material required for the preparation of the Reasons for Designation was prepared in the Spring/Summer of 2000 by the RBG's Policy, Planning and Co-ordination Intern, Sarah Stacey. -

Hamilton Historical Board Minutes February 13, 2007

HHB Template 09-09-04 Hamilton Historical Board Item 1.3 Community Services Committee Culture Section, Community Services Department MINUTES: Tuesday, February 13, 2007–12:30pm– The Stable at Whitehern Chair: Walter Peace Minute-Taker: Rebecca Oliphant Present: Graham Crawford, Robin McKee, Bob Williamson, Walter Peace, Mary Anderson, Pat Saunders, Elizabeth Shambrook, Jane Evans, Rebecca Oliphant Regrets: Bill Manson, Anna Bradford, John Johnston, Brian Henley, Art Bowes, Lorraine Marshall Guests: Absent: Item Agenda Person Decisions/Action Summary No. 1.1 Declaration of Interest Chair None 1.2 Approval of Agenda Chair Motion that the agenda of February 13, 2007 be approved. Moved: Elizabeth Shambrook / Seconded: Graham Crawford. Carried. 1.3 Review/Approval of Minutes Chair Motion that the minutes of January 16, 2007 be approved as amended. Moved: Elizabeth Shambrook / Seconded: Robin McKee. Carried. 2.0 Business Arising from Items not directly related to regular Agenda items the Minutes 3.0 Standing Items 3.1 Workplan Review Chair Action: Rebecca to locate email with template, distribute to Board for review March 20, 2007 Rebecca to find on email Walter has prepared letter for LACAC Action: Rebecca to provide name of new chair to Walter after LACAC meets Thursday. 3.2 Report Review/ Discussion Each liaison to provide their verbal report in writing (point form, highlights) to Rebecca for inclusion in January 2007 All minutes Battlefield House Museum & Park (Pat Saunders) – with recent snow tobogganing is an issue again, $300,000 from Ontario Ministry of Culture, official announcement will be made when Anna returns from Africa Hamilton Children’s Museum () – Dundurn National Historic Site – Dundurn Castle (Elizabeth Shambrook) – visits are up considerably, Robbie Burns dinner was well attended, Rolph Gates have been disassembled and moved to the east end of the park, HHB Template 09-09-04 Item Agenda Person Decisions/Action Summary No. -

"Modern Civic Art; Or, the City Made Beautiful": Aesthetic Progressivism and the Allied Arts in Canada, 1889-1939

"Modern Civic Art; or, the City Made Beautiful": Aesthetic Progressivism and the Allied Arts in Canada, 1889-1939 By Julie Nash A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Art History: Art and Its Institutions School For Studies in Art and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ©2011 Julie Nash Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-83094-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-83094-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

April NEB 2013 Publisher Layout

THETHE COMMUNITYCOMMUNITY NEWSLETTERNEWSLETTER OFOF HAMILTON’SHAMILTON’S NORTHNORTH ENDEND OCTOBERAPRIL 20082013 EDITION x x x x Photo from Norm Long Back row: Principal & coach Jack Bodden, Jack Wild, Alex Douglas, Billy Hammond, Norm Long, Rep. Board of Education Joe Mustos, Vern Laufman, Ray Yates, and coach Mr. Burtass. Front row: Jack Bryce, Ray Ford, Midge Padley, Bob Cooper and Jimmy Sanderson. National Volunteer Week, April 21 to 27, 2013 Volunteers make tremendous contributions to our North End Community. Our Community Partners offer a variety of volun- teer opportunities in the pages of this edition of the Breezes. If you would like to make a difference in 2013, just contact the Breezes’ community partner of your choice. Phone numbers and email addresses are published in their articles. You can visit Female Annas Humming Bird, above left their web pages for more details, too. Inside this issue: Feeding baby, above right Male Annas Humming Bird, Page 4 Book Club Corner left. Page 5 Randle Reef Photo by R. Wraight Page 8 April 8 to 14–Young Poets Week Pages 10 & 11 Community Event Listings Duck pair, getting ready for spring 2013 Photos by Dave Stevens CONNECTING SUPPORTING ENGAGING CREDITS & CONTACTS North End Breezes APRIL 2013 North End Breezes is published on the first day of LEAP (Low Income Energy Assistance Program) Are each month (except August) at: you at risk of having your Hydro disconnected? PAGE 2 Families and individuals needing financial assistance to pay their Hydro Bill can find information about the LEAP 438 Hughson Street North. Hamilton, Hamilton Community Legal Clinic Program at North Hamilton Community Health Centre.