HENRY ANSGAR KELLY Annotated Writings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spirit in the Liturgy by 2020, It Is Estimated That 41 Million of All U.S

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION of PASTORAL MUSICIANS PASTORAL March 2011 Music The Spirit in the Liturgy By 2020, it is estimated that 41 million of all U.S. Catholics will be Hispanic. 41million Are you ready to serve the worship needs of the fastest-growing segment in the Church? Join over two-thirds of the U.S. Catholic churches who turn to OCP for missals and hymnals to engage, unite and inspire their assembly in worship. 1-800-LITURGY (548-8749) | OCP.ORG NPM-January 2011:Layout 1 11/18/10 1:29 PM Page 1 Peter’s Way Tours Inc. Specializing in Custom Performance Tours and Pilgrimages Travel with the leader, as choirs have done for more than 25 years! This could be Preview a Choir Tour! ROME, ASSISI, VATICAN CITY your choir in Rome! Roman Polyphony JANUARY 19 - 26, 2012 • $795 (plus tax) HOLY LAND - Songs of Scriptures JANUARY 26-FEBRUARY 4, 2012 • $1,095 (plus tax) IRELAND - Land of Saints and Scholars FEBRUARY 14 - 20, 2012 • $995/$550* (plus tax) Continuing Education Programs for Music Directors Enjoy these specially designed programs at substantially reduced rates. Refundable from New York when you return with your own choir! *Special Price by invitation to directors bringing their choir within two years. 500 North Broadway • Suite 221 • Jericho, NY 11753 New York Office: 1-800-225-7662 Special dinner with our American and Peter’s Way Tours Inc. ERuerqopueeasnt Pau berio Ccahnutorere:s A gnronueptste a@llopweitnegr sfowr aysales.com Visit us at: www.petersway.com or call Midwest Office: 1-800-443-6018 positions have a responsibility to learn as much as we can about the new translation before we begin leading others to sing and pray with these new words. -

The Mysteries of Baptism and Chrismation

The Mysteries of Baptism and Chrismation 1 THE OFFICE FOR RECEIVING THOSE COMING TO THE ORTHODOX CHURCH FROM THE ANGLICAN CONFESSION The Priest shall stand at the doors of the church in epitrachelion and phelonion. And he questions the one converting to the Orthodox faith, saying: Priest: Do you wish to renounce the transgressions and errors of the Anglican Confession? Convert: I do. Priest: Do you wish to enter into union with the Orthodox-Catholic Faith? Convert: I do. Then the Priest blesses him (her), making the sign of the Cross with his right hand, saying: In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen. And laying his hand upon the bowed head of the convert, he recites the following prayer: Deacon: Let us pray to the Lord. Choir: Lord, have mercy. Priest: O Lord, God of truth, look down upon Thy servant (handmaiden), N., who seeks to make haste unto Thy Holy Orthodox Church, and to take refuge under her shelter. Turn him (her) from his (her) former error to the path of true faith in Thee, and grant him (her) to walk in all Thy commandments. Let Thine eyes ever look down upon him (her) with mercy, and let Thine ears hearken unto the voice of his (her) supplication, that he (she) may be numbered with Thine elect flock. For all the Powers of Heaven hymn Thee, and Thine is the glory: of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, now and ever, and unto the ages of ages. -

Cycle B Lectionary

FIRST SUNDAY OF ADVENT First Reading: Isaiah 63:16-17, 64:1-8 A reading from the book of the prophet Isaiah. You, YHWH , are our mother and father; “Our Redeemer Forever” is your name. YHWH , why do you let us wander from your ways and let our hearts grow too hard to revere you? Return to us for the sake of your children, the tribes of your heritage! Oh, that you would rend the heavens and come down, that the mountains would shake before you! As fire kindles the brushwood and the fire makes water boil, make your Name known to your adversaries, and let the nations tremble before you! When you did awesome things that we could not have expected, you came down, and the mountains quaked in your presence! From ages past no ear has ever heard, no eye ever seen any God but you intervening for those who wait for you! Oh, that you would find us doing right, that we would be mindful of you in our ways! You are angry because we are sinful; we sinned for so long — how can we be saved? All of us became unclean and soiled, even our good deeds are polluted. We have all withered like leaves, and our guilt carries us away like the wind. No one calls upon your Name, there are none who cling to you, for you hid your face from us and delivered us into the hands of our sins. Yet, you are our mother and father, YHWH ; we are the clay and you are the potter, we are all the work of your hands. -

I 'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': a NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF

'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': A NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF JUSTICES OF THE PEACE IN MID-TUDOR ENGLAND, 1547-1582 _____________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _____________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _____________ By Clarissa Elisabeth Hinojosa May 2014 i 'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': A NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF JUSTICES OF THE PEACE IN MID-TUDOR ENGLAND, 1547-1582 _____________ An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _____________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _____________ By Clarissa Elisabeth Hinojosa May 2014 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is a national study of English justices of the peace (JPs) in the mid- Tudor era. It incorporates comparable data from the reigns of Edward VI, Mary I, and the Elizabeth I. Much of the analysis is quantitative in nature: chapters compare the appointments of justices of the peace during the reigns of Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I, and reveal that purges of the commissions of the peace were far more common than is generally believed. Furthermore, purges appear to have been religiously- based, especially during the reign of Elizabeth I. There is a gap in the quantitative data beginning in 1569, only eleven years into Elizabeth I’s reign, which continues until 1584. In an effort to compensate for the loss of quantitative data, this dissertation analyzes a different primary source, William Lambarde’s guidebook for JPs, Eirenarcha. The fourth chapter makes particular use of Eirenarcha, exploring required duties both in and out of session, what technical and personal qualities were expected of JPs, and how well they lived up to them. -

Richard Kilburne, a Topographie Or Survey of The

Richard Kilburne A topographie or survey of the county of Kent London 1659 <frontispiece> <i> <sig A> A TOPOGRAPHIE, OR SURVEY OF THE COUNTY OF KENT. With some Chronological, Histori= call, and other matters touching the same: And the several Parishes and Places therein. By Richard Kilburne of Hawk= herst, Esquire. Nascimur partim Patriæ. LONDON, Printed by Thomas Mabb for Henry Atkinson, and are to be sold at his Shop at Staple-Inn-gate in Holborne, 1659. <ii> <blank> <iii> TO THE NOBILITY, GEN= TRY and COMMONALTY OF KENT. Right Honourable, &c. You are now presented with my larger Survey of Kent (pro= mised in my Epistle to my late brief Survey of the same) wherein (among severall things) (I hope conducible to the service of that Coun= ty, you will finde mention of some memorable acts done, and offices of emi= <iv> nent trust borne, by severall of your Ancestors, other remarkeable matters touching them, and the Places of Habitation, and Interment of ma= ny of them. For the ready finding whereof, I have added an Alphabeticall Table at the end of this Tract. My Obligation of Gratitude to that County (wherein I have had a comfortable sub= sistence for above Thirty five years last past, and for some of them had the Honour to serve the same) pressed me to this Taske (which be= ing finished) If it (in any sort) prove servicea= ble thereunto, I have what I aimed at; My humble request is; That if herein any thing be found (either by omission or alteration) substantially or otherwise different from my a= foresaid former Survey, you would be pleased to be informed, that the same happened by reason of further or better information (tend= ing to more certaine truths) than formerly I had. -

York Clergy Ordinations 1374-1399

York Clergy Ordinations 1374-1399 Edited by David M. Smith 2020 www.york.ac.uk/borthwick archbishopsregisters.york.ac.uk Online images of the Archbishops’ Registers cited in this edition can be found on the York’s Archbishops’ Registers Revealed website. The conservation, imaging and technical development work behind the digitisation project was delivered thanks to funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Register of Alexander Neville 1374-1388 Register of Thomas Arundel 1388-1396 Sede Vacante Register 1397 Register of Robert Waldby 1397 Sede Vacante Register 1398 Register of Richard Scrope 1398-1405 YORK CLERGY ORDINATIONS 1374-1399 Edited by DAVID M. SMITH 2020 CONTENTS Introduction v Ordinations held 1374-1399 vii Editorial notes xiv Abbreviations xvi York Clergy Ordinations 1374-1399 1 Index of Ordinands 169 Index of Religious 249 Index of Titles 259 Index of Places 275 INTRODUCTION This fifth volume of medieval clerical ordinations at York covers the years 1374 to 1399, spanning the archiepiscopates of Alexander Neville, Thomas Arundel, Robert Waldby and the earlier years of Richard Scrope, and also including sede vacante ordinations lists for 1397 and 1398, each of which latter survive in duplicate copies. There have, not unexpectedly, been considerable archival losses too, as some later vacancy inventories at York make clear: the Durham sede vacante register of Alexander Neville (1381) and accompanying visitation records; the York sede vacante register after Neville’s own translation in 1388; the register of Thomas Arundel (only the register of his vicars-general survives today), and the register of Robert Waldby (likewise only his vicar-general’s register is now extant) have all long disappeared.1 Some of these would also have included records of ordinations, now missing from the chronological sequence. -

Nicholas Love’S “Mirrour of the Blessed Life of Jesu Criste”

Eötvös Loránd University Faculty of Humanities DOCTORAL DISSERTATION PÉRI-NAGY ZSUZSANNA VOX, IMAGO, LITTERA: NICHOLAS LOVE’S “MIRROUR OF THE BLESSED LIFE OF JESU CRISTE” PhD School of Literature and Literary Theory Dr. Kállay Géza CSc Medieval and Early Modern Literature Programme Dr. Kállay Géza CSc Members of the defence committee: Dr. Kállay Géza CSc, chair Dr.Karáth Tamás, PhD, opponent Dr.Velich Andrea, PhD, opponent Dr. Pődör Dóra PhD Dr. Kiricsi Ágnes PhD Dr. Pikli Natália PhD Consultant: Dr. Halácsy Katalin PhD i Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................. IV LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................ V LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ................................................................................................ VI INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 7 I. THE MIRROUR AND THE ORTHODOX REFORM: AIMS ................................................................ 7 II. SOURCES: THE TEXT OF THE MIRROUR AND THE TWO ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPTS ........... 16 CHAPTER I. BACKGROUNDS: LAY DEVOTION, LOLLARDY AND THE RESPONSE TO IT 20 I. 1. LAY DEVOTION AND THE MEDITATIONES VITAE CHRISTI .................................................... 20 I. 2. LOLLARDY ........................................................................................................................ -

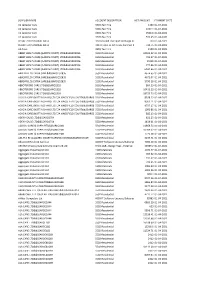

Payments to Suppliers Over £500 (ALL) April 2021

SUPPLIER NAME ACCOUNT DESCRIPTION NET AMOUNT PAYMENT DATE A1 Leicester Cars 3303-Taxi Hire 1160 01-04-2021 A1 Leicester Cars 3303-Taxi Hire 1037.4 01-04-2021 A1 Leicester Cars 3303-Taxi Hire 1504.8 01-04-2021 A1 Leicester Cars 3303-Taxi Hire 599.25 01-04-2021 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA 3201-Pooled Transport Recharge Inhouse 720 01-04-2021 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA 3113-Home to Sch Trans Contract Buses Sec 746.75 01-04-2021 AA Taxis 3303-Taxi Hire 1500 01-04-2021 ABBEY HEALTHCARE (AARON COURT) LTD&&SSARO2996 5502-Residential 34592.32 01-04-2021 ABBEY HEALTHCARE (AARON COURT) LTD&&SSARO2996 5502-Residential 703.57 01-04-2021 ABBEY HEALTHCARE (AARON COURT) LTD&&SSARO2996 5502-Residential 19218 01-04-2021 ABBEY HEALTHCARE (AARON COURT) LTD&&SSARO2996 5502-Residential 777.86 01-04-2021 ABBEY HEALTHCARE (AARON COURT) LTD&&SSARO2996 5502-Residential 6547.86 01-04-2021 ABBEYFIELDS EXTRA CARE&&SSAROE52835 5502-Residential 4674.65 01-04-2021 ABBEYFIELDS EXTRA CARE&&SSAROE52835 5502-Residential 4672.07 01-04-2021 ABBEYFIELDS EXTRA CARE&&SSAROE52835 5502-Residential 3790.28 01-04-2021 ABBOTSFORD CARE LTD&&SSARO2339 5502-Residential 864.29 01-04-2021 ABBOTSFORD CARE LTD&&SSARO2339 5502-Residential 10403.23 01-04-2021 ABBOTSFORD CARE LTD&&SSARO2339 5502-Residential 18725.73 01-04-2021 ACACIA CARE (NOTTINGHAM) LTD T/A KINGSFIELD COURT&&SSARO85405502-Residential 8528.12 01-04-2021 ACACIA CARE (NOTTINGHAM) LTD T/A KINGSFIELD COURT&&SSARO85405502-Residential 9052.71 01-04-2021 ACACIA CARE (NOTTINGHAM) LTD T/A KINGSFIELD COURT&&SSARO85405502-Residential 9707.17 -

Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.T65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-78218-0 - The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, Volume II 1100-1400 Edited by Nigel Morgan and Rodney M. Thomson Index More information General index A Description of England 371 A¨eliz de Cund´e 372 A talking of the love of God 365 Aelred of Rievaulx xviii, 6, 206, 322n17, 341, Abbey of the Holy Ghost 365 403n32 Abbo of Saint-Germain 199 Agnes (wife of Reginald, illuminator of Abel, parchmenter 184 Oxford) 178 Aberconwy (Wales) 393 Agnes La Luminore 178 Aberdeen 256 agrimensores 378, 448 University 42 Alan (stationer of Oxford) 177 Abingdon (Berks.), Benedictine abbey 111, Alan de Chirden 180–1 143, 200, 377, 427 Alan of Lille, Anticlaudianus 236 abbot of, see Faricius Proverbs 235 Chronicle 181, 414 Alan Strayler (illuminator) 166, 410 and n65 Accedence 33–4 Albion 403 Accursius 260 Albucasis 449 Achard of St Victor 205 Alcabitius 449 Adalbert Ranconis 229 ‘Alchandreus’, works on astronomy 47 Adam Bradfot 176 alchemy 86–8, 472 Adam de Brus 440 Alcuin 198, 206 Adam of Buckfield 62, 224, 453–4 Aldhelm 205 Adam Easton, Cardinal 208, 329 Aldreda of Acle 189 Adam Fraunceys (mayor of London) 437 Alexander, Romance of 380 Adam Marsh OFM 225 Alexander III, Pope 255, 372 Adam of Orleton (bishop of Hereford) 387 Alexander Barclay, Ship of Fools 19 Adam de Ros, Visio S. Pauli 128n104, 370 Alexander Nequam (abbot of Cirencester) 6, Adam Scot 180 34–5, 128n106, 220, 234, 238, 246, Adam of Usk 408 451–2 Adelard of Bath 163, 164n137, 447–8, De naturis rerum 246 450–2 De nominibus utensilium 33, 78–9 Naturales -

Revue Française De Civilisation Britannique, XVIII-1 | 2013 Orthodoxy, Heresy and Treason in Elizabethan England 2

Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique French Journal of British Studies XVIII-1 | 2013 Orthodoxie et hérésie dans les îles Britanniques Orthodoxy, Heresy and Treason in Elizabethan England Orthodoxie, hérésie et trahison dans l’Angleterre élisabéthaine Claire Cross Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/3561 DOI: 10.4000/rfcb.3561 ISSN: 2429-4373 Publisher CRECIB - Centre de recherche et d'études en civilisation britannique Printed version Date of publication: 1 March 2013 ISBN: 2-911580-37-0 ISSN: 0248-9015 Electronic reference Claire Cross, « Orthodoxy, Heresy and Treason in Elizabethan England », Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique [Online], XVIII-1 | 2013, Online since 01 March 2013, connection on 20 March 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/3561 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/rfcb.3561 This text was automatically generated on 20 March 2020. Revue française de civilisation britannique est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Orthodoxy, Heresy and Treason in Elizabethan England 1 Orthodoxy, Heresy and Treason in Elizabethan England Orthodoxie, hérésie et trahison dans l’Angleterre élisabéthaine Claire Cross 1 Despite the severe penalties laid down in the Acts of Supremacy and Uniformity of 1559, the Elizabethan Government initially displayed great unwillingness to proceed against Catholics for their religious beliefs, but changed its stance on the promulgation of the papal bull of 1570 which excommunicated the queen and released her subjects from their allegiance. At the beginning of the reign, Protestant and Catholic controversialists in their publications concentrated upon whether the English Church could be considered to be a true Church; after the State began prosecuting seminary priests and their lay protectors for treason, the debate moved on to whether Catholics were being put to death exclusively for a political crime or sacrificing their lives solely for their faith. -

1 Rev. Andrew D. Ciferni , O. Praem., STL, Ph.D

Rev. Andrew D. Ciferni , O. Praem., S.T.L., Ph.D. _________________________ Annotated Bibliography --2012— Ciferni, O. Praem., Andrew D., general editor. The Liturgy of the Hours for Daylesford Abbey (Paoli, PA), Santa Maria de la Vid Abbey (Albuquerque, NM, and Saint Norbert Abbey (De Pere, WI). Gaudeamus (2008), Celebrantes (2011), Laudate (2012). Paoli, PA: Daylesford Abbey. --2011— ___________ “Homily for the 24th Sunday in Ordinary Time: Tenth Anniversary Service of 9/11.” Communicator XXVIII:2. (December 2011). 47-49 --2010-- ___________ “Why a Pipe Organ?” Church of Saint Monica Bulletin. (February 2010). 5. --2009— ____________God Against Religion. By Matthew Myer Boulton. Book Review. Worship 83:2. March 2009. 188 – 189. ____________.“Even the Walls Can Teach.” Company. (Winter 2009 – 2010). 12 – 13. --2008— --2007— ___________ Preface to Norbert and Early Norbertine Spirituality selected and introduced by Theodore J. Antry, O.Praem., and Carol Neel. The Classics of Western Spirituality. New York and Mahwah: Paulist Press, 2007. xi – xii. ____________“The Lucernarium.” Monastic Liturgy Forum Newsletter. (Winter 2007). 1 – 5. ____________ “Some Reflections on What Distinguishes Norbertines or Premonstratensian Charism at st the Dawn of the 21 Century.” Communicator XXV:2 . (December 2007). 13-18. --2006— ___________ “Homily on the 39th Anniversary of the Dedication of the Daylesford Abbey Church.” Communicator XXIV:2.(December 2006). 64-66. 1 ___________ “Phyllis Martin, O. Praem. Obl. (1923 – 2006).” Communicator XXIV:2. (December 2006). 47-48 & 53. ____________This is the Night: Suffering, Salvation and the Liturgies of Holy Week. By James W. Farrell. Review. Worship. 80:1. (January 2006). 90 – 91. ____________“Holy People, Holy Places,” Church. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk i UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES School of History The Wydeviles 1066-1503 A Re-assessment by Lynda J. Pidgeon Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 15 December 2011 ii iii ABSTRACT Who were the Wydeviles? The family arrived with the Conqueror in 1066. As followers in the Conqueror’s army the Wydeviles rose through service with the Mowbray family. If we accept the definition given by Crouch and Turner for a brief period of time the Wydeviles qualified as barons in the twelfth century. This position was not maintained. By the thirteenth century the family had split into two distinct branches. The senior line settled in Yorkshire while the junior branch settled in Northamptonshire. The junior branch of the family gradually rose to prominence in the county through service as escheator, sheriff and knight of the shire.