Training Evaluation Model: Evaluating and Improving Criminal Justice Training

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil Rights2018v2.Key

UNITED STATES HISTORY Civil Rights Era Jackie Robinson Integrates “I Have a Dream” MLB 1945-1975 March on Washington Little Rock Nine 1963 1957 Brown vs Board of Ed. 1954 Civil Rights Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Workers Murdered born 1929 - assassinated1968 1964 Vocabulary • Separate, but Equal - Supreme Court decision that said that separate (but equal) facilities, institutions, and laws for people of different races were were permitted by the Constitution • Segregation - separation of people into groups by race. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, riding public transportation, or any public activity • Jim Crow laws - State and local laws passed between 1876 and 1965 that required racial segregation in all public facilities in Southern states that created “legal separate but equal" treatment for African Americans • Integration laws requiring public facilities to be available to people of all races; It’s the opposite of segregation Vocabulary • Civil Disobedience - Refusing to obey certain laws, demands, and commands of a government as a form of non-violent protest - it was used by Gandhi in India and Dr. King in the USA • 13th Amendment - Constitutional amendment that abolished slavery - passed in 1865 • 14th Amendment - Constitutional amendment that guaranteed equal protection of the law to all citizens - passed in 1868 • Lynching - murder by a mob, usually by hanging. Often used by racists to terrorize and intimidate African Americans • Civil Rights Act of 1964 - Law proposed by President Kennedy and eventually made law under President Johnson. The law guaranteed voting rights and fair treatment of African Americans especially in the Southern States People • Mohandus Gandhi (1869-1948) - Used non-violent civil disobedience; Led India to independence and inspired movements for non-violence, civil rights and freedom across the world; his life influenced Dr. -

SPRING 2013 CONTENTS Spring 2013

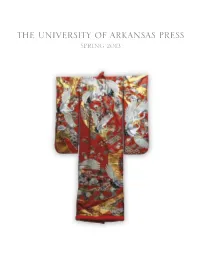

THE UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS PRESS SPRING 2013 CONTENTS spring 2013 New University of Arkansas Press Books 1–15 DISTRIBUTED PRESSES: Butler Center Books 16–19 Moon City Press 20–21 UpSet Press 22 Ozark Society Foundation 23 DVDs 23 John exhorting his runners from his usual spot behind the first curve at the Tyson Center. Photo courtesy of University of Arkansas Media Relations. Selected Backlist 24–26 Notable Reviews 27 “John McDonnell is not only one of Order Form 28 the greatest track and cross-country Sales Representatives 29 coaches ever but a national treasure Ordering Information 29 whose influence on the sport and on the young men he’s nurtured will last for generations. McDonnell’s life story illuminates the subtle ways in which he acquired and expanded on the knowledge that led to a record The University of Arkansas Press number of NCAA titles while gaining is moving to electronic catalogs. insights into both the psychology and physiology that produced peak perfor- To continue to receive our catalog, mances. A fascinating book.” make sure you are on our e-mail list. —MARC BLOOM, track and field journalist and Send your name and email address to author of God on the Starting Line [email protected] facebook.com/uarkpress @uarkpress COVER: Vintage kimono owned by Miyoko Sasaki McDonald, mother of Jan Morrill, author of The Red Kimono (page 4). Miyoko was seven years old when she and her family were relocated to Tule Lake Internment Camp in California. They were later The Razorback track team is greeted by Arkansas governor Bill moved to Topaz Internment Camp in Utah. -

Remarks on Signing Legislation to Establish the Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site November 6, 1998

Administration of William J. Clinton, 1998 / Nov. 6 Remarks on Signing Legislation To Establish the Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site November 6, 1998 Thank you very much. You know, when Ernie rorist attack. No nation should live under the was up here introducing me, I remembered that threat of violence and terror that they live under he was the only senior among the Little Rock every day. Nine. He graduated in the spring in 1958, and When Prime Minister Netanyahu and Chair- when they called him up to receive his diploma, man Arafat signed the Wye River agreement, the whole auditorium was quiet, not a single they knew they would face this moment. They person clapped. But we're all clapping for you knew when they went home both of them would today, buddy. be under more danger and the terrorists would I would like to thank all the members of target innocent civilians. They knew they would the Little Rock Nine who are here, including have to muster a lot of courage in their people Elizabeth Eckford, Carlotta LaNier, Jefferson to stick to the path of peace in the face of Thomas, Minnijean Trickey, Terrence Roberts. repeated acts of provocation. Melba Pattillo Beals is not here. Gloria Ray There are some people, you know, who have Karlmark is not here. Thelma Mothershed-Wair a big stake in the continuing misery and hatred is not here. I think we should give all of them in the Middle East, and indeed everywhere else another hand. [Applause] in this whole world, just like some people had I would like to thank Congressman Elijah a big stake in continuing it in Little Rock over Cummings, Congressman Gregory Meeks for 40 years ago. -

Kimberly West-Faulcon PROFESSIONAL ACADEMIC

Kimberly West-Faulcon JAMES P. BRADLEY CHAIR IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW AND PROFESSOR OF LAW LOYOLA LAW SCHOOL 919 ALBANY STREET LOS ANGELES, CA 90015 (213) 736-8172 • [email protected] • http://www.lls.edu/academics/faculty/west-faulcon.html PROFESSIONAL ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE LOYOLA LAW SCHOOL Los Angeles, CA 2011-Present James P. Bradley Chair in Constitutional Law 2010-Present Professor of Law 2005-2010 Associate Professor of Law Courses: Constitutional Law; Advanced Topics in Constitutional Law: Originalism; Advanced Topics in Constitutional Law: Abortion, Race, Sex, & Gender Identity; Advanced Topics in Constitutional Law: Second Amendment, Equal Protection, & Religion; Constitutional Law I ⅈ Intelligence, Testing, and the Law; Employment Discrimination Law; Principles of Social Justice; Social Justice Lawyering USC GOULD SCHOOL OF LAW Los Angeles, CA 2016-2019 Visiting Professor Course: Constitutional Law: Rights (Fall 2016, Spring 2018, & Fall 2019) SOUTHWESTERN LAW SCHOOL Los Angeles, CA 2017 Visiting Professor Courses: Constitutional Law II (Fall 2017) UCLA SCHOOL OF LAW Los Angeles, CA 2013-2015 Visiting Professor Courses: Constitutional Law I (Fall 2013); Employment Discrimination Law (Fall 2014), Civil Rights (Spring 2015) 2010 Visiting Professor Course: Intelligence, Testing, and the Law 2004 Visiting Lecturer Course: Race-Conscious Remedies (with Professor Cheryl Harris) EDUCATION 1992-1995 YALE LAW SCHOOL New Haven, CT Juris Doctor Yale Law Journal, Senior Editor Research Assistant to Sterling Professor of Law Owen M. Fiss Project SAT, Founder, Director and Tutor (free SAT tutoring program for New Haven youth) Black Law Students Association, Community Outreach Chair Frederick Douglass Moot Court 1988-1992 DUKE UNIVERSITY Durham, NC Bachelor of Arts, summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa GPA: 3.9 (Class Rank: 9 of 1182) President, Duke Democrats Dukes and Duchesses, Duchess Student Ambassador C.H.A.N.C.E. -

Choices in LITTLE ROCK

3434_LittleRock_cover_F 5/27/05 12:58 PM Page 1 Choices IN LITTLE ROCK A FACING HISTORY AND OURSELVES TEACHING GUIDE ••••••••• CHOICES IN LITTLE ROCK i Acknowledgments Facing History and Ourselves would like to offer special thanks to The Yawkey Foundation for their support of Choices in Little Rock. Facing History and Ourselves would like to acknowledge the valuable assistance it received from the Boston Public Schools in creating Choices in Little Rock. We are particularly appreciative of the team that consulted on the development of the unit under the leadership of Sidney W. Smith, Director, Curriculum and Instructional Practices, and Judith Berkowitz, Ed.D., Project Director for Teaching American History. Patricia Artis, history coach Magda Donis, language acquisitions coach Meira Levinson, Ph.D., teacher, McCormack Middle School Kris Taylor, history coach Mark Taylor, teacher, King Middle School Facing History and Ourselves would also like to offer special thanks to the Boston Public School teachers who piloted the unit and provided valuable suggestions for its improvement. Constance Breeden, teacher, Irving Middle School Saundra Coaxum, teacher, Edison Middle School Gary Fisher, teacher, Timilty Middle School Adam Gibbons, teacher, Lyndon School Meghan Hendrickson, history coach, former teacher, Dearborn Middle School Wayne Martin, Edwards Middle School Peter Wolf, Curley Middle School Facing History and Ourselves values the efforts of its staff in producing and implementing the unit. We are grateful to Margot Strom, Marc Skvirsky, Jennifer Jones Clark, Fran Colletti, Phyllis Goldstein, Jimmie Jones, Melinda Jones-Rhoades, Tracy O’Brien, Jenifer Snow, Jocelyn Stanton, Chris Stokes, and Adam Strom. Design: Carter Halliday Associates www.carterhalliday.com Printed in the United States of America 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 November 2009 ISBN-13: 978-0-9798440-5-8 ISBN-10: 0-9798440-5-3 Copyright © 2008 Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation, Inc. -

Modern Civil Rights

Contents: Modern Civil Rights Limited progress, early court cases Thurgood Marshall Welcome! Briggs & Bolling cases Brown case/Earl Warren These mini-lectures are an overview of your Reactions to Brown assigned readings—they should provide Rosa Parks & Montgomery better understanding of what you are reading! Martin Luther King/SCLC Little Rock desegregation/reactions Just listen (if audio is provided, it plays Sit-ins/Freedom Rides automatically), then read the slide, and use James Meredith & universities the next arrowhead. If you are viewing this in March on Washington PDF, use the down arrow at the top of the pdf. Assassination/LBJ Great Society Conclusions. & A brief post test. Civil Rights... • Race laws based on 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson…separate but equal • Very few early challenges –W.E.B. DuBois created NAACP 1905 –Racial issues delayed in emergencies of world wars and depression ch29,Holland 2 Limited Progress, 1930s... • FDR & Eleanor Roosevelt gave limited support to Civil Rights • Margold Report (NAACP), 1933 –suggested tactics to challenge Plessy • Legal Defense Fund (LDF) started in 1939 ch29,Holland 3 First Challenges... • NAACP planned to challenge the separation of public education… • Thurgood Marshall and others collected facts for a court case... • President Truman’s Civil Rights Commission supported action ch29,Holland 4 Thurgood Marshall and NAACP lawyers gather evidence. Lead counsel, Thurgood Marshall whom LBJ would later make a Supreme Court Justice Law School Case... • 1946--Univ. Texas Law School denied admission to blacks • NAACP sued & Texas opened a small black law school; • Texas won the law suit since separate schools were legally provided ch29,Holland 7 Shall We Target Public Schools...? • By the 1950s four approaches to separating the races in schools… –Northern states required integration –Southern states required segregation –Border states like Kansas allowed county option –Western states had no law either way ch29,Holland 8 1949 Briggs v. -

Choosing to Participate and the Re-Release of This Book Which Has Been Developed to Give Educators a Tool to Explore the Role of Citizenship in Democracy

R evised E Praise for dition FACING HISTORY AND OURSELVES A FACING HISTORY AND OURSELVES PUBLICATION C We are well aware of the forces beyond our control—the attitudes, modes of H behavior, and unexamined assumptions that often, sadly, govern the larger OOSING society, and that undermine the school communities we seek to build. It is to this end that we find Facing History so powerful. From both discussions with teachers and observations of student interaction, it is clear that Facing TO History and Ourselves is a tremendously effective vehicle for engaging P ARTICI students in the critical dialogues essential for a tolerant and just society. Dan Isaacs P Former Assistant Superintendent ATE of the Los Angeles Unified School District • A Facing History and Facing History and Ourselves has become a standard for ambitious and CHOOSING TO courageous educational programming…. At a time when more and more of our population is ignorant about history, and when the media challenge PARTICIPA T E the distinction between truth and fiction—indeed, the very existence of REVISED EDITION truth—it is clear that you must continue to be the standard. Howard Gardner O Professor of Education, Harvard Graduate School of Education urselves Publication Teaching kids to fight intolerance and participate responsibly in their world is the most important work we can do. Matt Damon, Actor, Board of Trustees Member & Former Facing History and Ourselves Student Headquarters 16 Hurd Road Brookline, MA 02445 (617) 232-1595 www.facinghistory.com Visit choosingtoparticipate.org for additional resources, inspiring stories, ways to share your story, and a 3D immersive environment of the exhibition for use in the classroom and beyond. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 452 104 SO 031 665 AUTHOR Harris, Laurie Lanzen, Ed.; Abbey, Cherie D., Ed. TITLE Biography Today: Profiles of People of Interest to Young Readers, 2000. ISSN ISSN-1058-2347 PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 504p. AVAILABLE FROM Omnigraphics, 615 Griswold Street, Detroit, MI 48226 (one year subscription: three softbound issues, $55; hardbound annual compendium, $75; individual volumes, $39). Tel: 800-234-1340 (Toll Free); Fax: 800-875-1340 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.omnigraphics.com/. PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) Reference Materials General (130) JOURNAL CIT Biography Today; v9 n1-3 Jan-Sept 2000 EDRS PRICE MF02/PC21 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Literature; Biographies; Childrens Literature; Elementary Secondary Education; Individual Characteristics; Life Events; Popular Culture; *Profiles; Readability; Role Models; Social Studies; Student Interests IDENTIFIERS *Biodata; Obituaries ABSTRACT This is the ninth volume of a series designed and written for young readers ages 9 and above. It contains three issues and profiles individuals whom young people want to know about most: entertainers, athletes, writers, illustrators, cartoonists, and political leaders. The publication was created to appeal to young readers in a format they can enjoy reading and readily understand. Each entry provides at least one picture of the individual profiled, and bold-faced rubrics lead the reader to information on birth, youth, early memories, education, first jobs, marriage and family, career highlights, memorable experiences, hobbies, and honors and awards. Each entry ends with a list of easily accessible sources (both print and electronic) designed to guide the student to further reading on the individual. Obituary entries also are included, written to provide a perspective on an individual's entire career. -

鋢茚t茜 U苌闱 Ia U蓆躻 by Xw鈜t鄚汕

The Ipet-Isut Historical Preservation Foundation Presents à{ VÉÅÅxÅÉÜtà|Çz à{x HC TÇÇ|äxÜátÜç UÜÉãÇ iA UÉtÜw by Xwâvtà|ÉÇ ATTORNEY CHARLES HAMILTON HOUSTON THURGOOD MARSHALL, SUPREME COURT JUSTICE ATTORNEY WILLIAM MEREDITH HOLLAND You have a large number of people who never heard of Charlie Houston. But you're going to hear about him. That man was the engineer of all of it... if you do it legally, Charlie Houston made it possible.... -- Thurgood Marshall Historical Timeline of Black Education in Palm Beach County Florida Researched and Edited by Kimela I. Edwards Ineria E. Hudnell Margaret S. Newton Debbye G. R. Raing Copyright © 2004 The Ipet-Isut Historical Preservation Foundation All Rights Reserved “Discrimination in education is symbolic of all the more drastic discrimination in which Negroes suffer. In the American life, the equal protection clause in the 14th Amendment furnishes the key to ending separate schools.” Charles Hamilton Houston Brown itself is made up of five cases. This collection of cases was the culmination of years of legal groundwork laid by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in its work to end segregation. None of the cases would have been possible without individuals who were courageous enough to take a stand against the segregated system. Briggs v. Elliot The Briggs case was named for Harry Briggs, one of twenty parents who brought suit against R.W. Elliot, the president of the school board for Clarendon County, South Carolina. Initially, parents had only asked the county to provide school buses for the Black students as they did for Whites. -

Congressional Gold Medals, 1776-2016

Congressional Gold Medals, 1776-2016 Matthew Eric Glassman Analyst on the Congress February 13, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30076 Congressional Gold Medals, 1776-2015 Summary Senators and Representatives are frequently asked to support or sponsor proposals recognizing historic events and outstanding achievements by individuals or institutions. Among the various forms of recognition that Congress bestows, the Congressional Gold Medal is often considered the most distinguished. Through this venerable tradition, the occasional commissioning of individually struck gold medals in its name, Congress has expressed public gratitude on behalf of the nation for distinguished contributions for more than two centuries. Since 1776, this award, which initially was bestowed on military leaders, has also been given to such diverse individuals as Sir Winston Churchill and Bob Hope, George Washington and Robert Frost, Joe Louis and Mother Teresa of Calcutta. Members of Congress and their staff frequently ask questions concerning the nature, history, and contemporary application of the process for awarding Gold Medals. This report responds to congressional inquiries concerning this process, and includes a historical examination and chronological list of these awards. It is intended to assist Members of Congress and staff in their consideration of future Gold Medal proposals, and will be updated as Gold Medals are approved. Congressional Research Service Congressional Gold Medals, 1776-2015 Contents Practices Adopted During the -

Daily Digest

Thursday, September 24, 1998 Daily Digest HIGHLIGHTS The House agreed to the conference report on H.R. 4112, Legislative Branch Appropriations for FY 1999. The House agreed to the conference report on H.R. 3616, DOD Author- ization for FY 1999. The House passed H.R. 3736, Workforce Improvement and Protection Act. House Committee ordered reported 7 sundry measures. Senate Measures Passed: Chamber Action Congressional Gold Medal: Senate passed H.R. Routine Proceedings, pages S10865±S10943 3506, to award a congressional gold medal to Gerald Measures Introduced: Six bills and one resolution R. and Betty Ford, after agreeing to the following were introduced, as follows: S. 2514±2519 and S. amendment proposed thereto: Pages S10941±42 Res. 282. Pages S10920±21 McCain (for D'Amato) Amendment No. 3647, to Measures Reported: Reports were made as follows: award congressional gold medals to Jean Brown S. 1405, to provide for improved monetary policy Trickey, Carlotta Walls LaNier, Melba Patillo Beals, and regulatory reform in financial institution man- Terrence Roberts, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Thelma agement and activities, to streamline financial regu- Mothershed Wair, Ernest Green, Elizabeth Eckford, latory agency actions, to provide for improved con- and Jefferson Thomas, commonly referred to collec- sumer credit disclosure, and for other purposes, with tively as the ``Little Rock Nine'', on the occasion of an amendment in the nature of a substitute. (S. the 40th anniversary of the integration of the Cen- Rept. No. 105±346) tral High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. H.R. 378, for the relief of Heraclio Tolley. Pages S10941±42 H.R. -

Little Rock Nine

National Park Service Little Rock Central U.S. Department of the Interior Little Rock Central High School High School National Historic Site The Little Rock Nine The Little Rock Nine in front of Central High School, September 25, 1997. The Nine are l to r: Thelma Mothershed Wair, Minnijean Brown Trickey, Jefferson Thomas, Terrence Roberts, Carlotta Walls LaNier, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Ernest Green, Elizabeth Eckford, and Melba Pattillo Beals. Behind the Nine are, l to r: Little Rock Mayor Jim Dailey, Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee, and President William Jefferson Clinton. Photo by Isaiah Trickey. Who Are The Little Rock In 1957, nine ordinary teenagers walked out of their homes and stepped up to the front Nine? lines in the battle for civil rights for all Americans. The media coined the name “Little Rock Nine,” to identify the first African-American students to desegregate Little Rock Central High School. The End of Legal In 1954, the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka “[Blossom said] you’re not going to be able to go Segregation Supreme Court decision outlawed segregation in to the football games or basketball games. You’re public education. Little Rock School District not going to be able to participate in the choir or Superintendent Virgil Blossom devised a plan of drama club, or be on the track team. You can’t go gradual integration that would begin at Central to the prom. There were more cannots…” High School in 1957. The school board called for Carlotta Walls LaNier volunteers from all-black Dunbar Junior High and Horace Mann High School to attend Central.