Laozi, a Lost Prophet?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dictionary of Chinese Deities

THE DICTIONARY OF CHINESE DEITIES HAROLD LIU For everyone who love Chinese myth A Amitabha Amitabha is is a celestial buddha described in the scriptures of the Mahayana school of Buddhism. Amitabha is the principal buddha in the Pure Land sect, a branch of Buddhism practiced mainly in East Asia. An Qisheng An immortal who had live 1.000 year at he time of Qin ShiHuang. According to the Liexian Zhuan, Qin Shi Huang spoke with him for three entire days (including nights), and offered Anqi jade and gold. He later sent an expedition under Xu Fu to find him and his highly sought elixir of life. Ao Guang The dragon king of East sea. He is the leader of four dragon king. His son Ao Bing killed by Nezha, when his other two son was also incapitated by Eight Immortals. Ao Run The dragon king of West Sea. His crown prine named Mo Ang and help Sun Wukong several times in journey to the West story.His 3th son follow monk XuanZhang as hisdragon horse during Xuan Zhang's journey to the West. Ao Qin The dragon king of South sea AoShun The dragon King of North sea. Azzure dragon (Qing Long) One of four mythical animal in China, he reincanated many times as warrior such as Shan Xiongxin and Yom Kaesomun, amighty general from Korea who foiled Chinese invasion. It eleemnt is wood B Bai He Tongzhu (white crane boy) Young deity disciple of Nanji Xianweng (god of longevity), he act as messenger in heaven Bai Mudan (White peony) Godess of temptress Famous prostitute who sucesfully tempt immortal Lu Dongbin to sleep with her and absorb his yang essence. -

Yu-Huang -- the Jade Emperor

יו הואנג يو هوانج https://www.scribd.com/doc/55142742/16-Daily-Terms ヒスイ天使 Yu-huang -- The Jade Emperor Yu-huang is the great High God of the Taoists -- the Jade Emperor. He rules Heaven as the Emperor doe Earth. All other gods must report to him. His chief function is to distribute justice, which he does through the court system of Hell where evil deeds and thoughts are punished. Yu- huang is the Lord of the living and the dead and of all the Buddhas, all the gods, all the spectres and all the demons. According to legend he was the son of an emperor Ch'ing-te and his wife Pao Yueh-kuang who from his birth exhibited great compassion. When he had been a few years on the throne he abdicated and retired as a hermit spending his time dispensing medicine and knowledge of the Taoist texts. Some scholars see in this a myth of the sacred union of the sun and the moon, their son being the ruler of all Nature. "The good who fulfill the doctrine of love, and who nourish Yu-huang with incense, flowers, candles and fruit; who praise his holy name with respect and propriety -- such people will receive thirty kinds of very wonderful rewards." --Folkways in China L Holdus. http://www.chebucto.ns.ca/Philosophy/Taichi/gods.html Jade Emperor The Jade Emperor (Chinese: 玉皇; pinyin: Yù Huáng of the few myths in which the Jade Emperor really shows or 玉帝, Yù Dì) in Chinese culture, traditional religions his might. and myth is one of the representations of the first god (太 In the beginning of time, the earth was a very difficult 帝 tài dì). -

Appendix 2 Chinese Deities and Spirits

Appendix 2 Chinese deities and spirits This appendix includes a selection of the most common and important gods, goddesses, Buddhas, bodhisattvas, ancestors, and spirits that one can find in reli- gious sites across China. For each major religion, I present the most important deities of the pantheon as people would encounter them in a temple or other sacred space. Of course, there are many other deities presented in temples across China; yet, these are some of the most common of the range of deities – which ultimately cover all aspects of people’s physical and spiritual lives. Animistic ideas (referring to the idea of having or expecting mutually recip- rocal relationships of respect, gift-exchange, and communication; see Harvey 2013) in China stem at least as far back as the proto-Daoist text, the Zhua¯ngzi 庄子, from around 300 BCE, the first seven, inner chapters of which scholars think were written by Zhua¯ ng Zho¯u 庄周 (c. 369 BCE – c. 286 BCE). This text explains ideas about carefree living, naturalness, and relativity of perceptions, and Zhua¯ ngzi seems to attempt to get people to recognize that they live in a multi- species symbiotic community in which each aspect is in relationship and that each deserves respect. The Zhua¯ ngzi continues to be a widely-read and influential book among contemporary Chinese readers. Other popular literary texts include religiously-informed animistic ideas as well. Journey to the West (Xı¯yóujì 西游记), The Investiture of the Gods (Fe¯ngshén Yaˇnyì 封神演义), Dream of the Red Chamber (Hónglóu mèng 红楼梦), and the Water Margin (Shuıˇ huˇ zhuàn 水浒传; aka., Outlaws of the Marsh), all contain examples of some natural phenomenon such as a rock, animal, or flower, which has absorbed the essence of the cosmos for so long that it becomes a spirit being and chooses to incarnate in the human world to experience life in a human form. -

![Tao Te Ching [1] and the Founder of 老子 Philosophical Taoism, but He Is Also Revered As a Deity in Religious Taoism and Traditional Chinese Religions](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9996/tao-te-ching-1-and-the-founder-of-philosophical-taoism-but-he-is-also-revered-as-a-deity-in-religious-taoism-and-traditional-chinese-religions-1579996.webp)

Tao Te Ching [1] and the Founder of 老子 Philosophical Taoism, but He Is Also Revered As a Deity in Religious Taoism and Traditional Chinese Religions

老子天使 לאו דזה 老子 ﻻو تسي Λάου-Τζε Laozi - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lao_Tzu Laozi From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Lao Tzu) Laozi (also Lao-Tzu, Lao-Tsu , or Lao-Tze ) was a philosopher and poet of ancient China. He is best known as Laozi the reputed author of the Tao Te Ching [1] and the founder of 老子 philosophical Taoism, but he is also revered as a deity in religious Taoism and traditional Chinese religions. Although a legendary figure, he is usually dated to around the 6th century BC and reckoned a contemporary of Confucius, but some historians contend that he actually lived during the Warring States period of the 5th or 4th century BC. [2] A central figure in Chinese culture, Laozi is claimed by both the emperors of the Tang dynasty and modern people of the Li surname as a founder of their lineage. Throughout history, Laozi's work has been embraced by various anti-authoritarian movements. [3] Contents 1 Names 2 Historical views Laozi, depicted as Daode Tianzun 3 Tao Te Ching Born Zhou Dynasty 3.1 Taoism Died Zhou Dynasty 4 Influence 4.1 Eremitism Era Ancient philosophy 4.2 Politics Region Chinese philosophy 5 References School Taoism 5.1 Footnotes Notable ideas Wu wei 5.2 Bibliography Influenced 6 Further reading 7 External links Names [4] In traditional accounts, Laozi's personal name is usually given as Li Er (李耳, Old *Rəʔ N əʔ, Mod. Lǐ Ěr) and [4] his courtesy name as Boyang (trad. 伯陽, simp. -

The Taoist Religion

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/taoistreligionOOpark : ,The Taoist Religion BY E. H. PARKER {Professor of Chinese at the Owens College). I REPRINTED FROM THE "DUBLIN REVIEW. PRICE Is. 6d. / Xonfcon LUZAC & CO., OREIGN AND ORIENTAL PUBLISHERS, ETC., 46 GREAT RUSSELL STREET, W. {Opposite the British Museum.) : The Taoist Religion i E. H.^ PARKER (Professor of Chinese at the Owens College). REPRINTED FROM THE "DUBLIN REVIEW." PRICE Is. 6<L Xonfcon LUZAC & CO., FOREIGN AND ORIENTAL PUBLISHERS, ETC., 46 GREAT RUSSELL STREET, W. (Opposite the British Museum.) 1925 ?37 59B278 8 a .54 THE TAOIST RELIGION, little is a significant fact that, whilst comparatively so IT has yet been done in the fields of Chinese etymology and history, where an ample supply of exact knowledge is at hand, almost every foreigner who has either seriously studied or superficially toyed with Chinese philosophical literature, where everything is so vague, considers himself at liberty to expatiate upon Taoism, although Confucius himself frankly declared it to be rather beyond his compre- hension, even when explained by the Taoist prophet him- self. Personally I have, for better or for worse, succeeded in surviving the nineteenth century without falling a victim if, thirty-five years to the fashionable cacoethes ; and after of dalliance with Chinese books, I at last yield to the tempter, I may at least be permitted to plead in palliation that I only commit in my approaching dotage that rash act which others have perpetrated in the heyday of their youth and fame. -

Guidelines for Setting up a Daoist Altar

Guidelines for Setting up a Daoist Altar By Chris Grabowski, Daoshi Wu Wei Lin, ADGL Altars are very personal things, and form the locus for one’s daily spiritual practice. It contains symbolic representations of deities or concepts held sacred to the adept. It also contains ritual implements to aid in paying homage to those deities or concepts. There are many articles on the Internet regarding Buddhist altars, but there are far fewer resources for Daoists. Here are some guidelines for setting up an altar specific to the practice of Quanzhen Daoism, its proper care, maintenance, and use. Throughout this article I will make reference to the altar in my shrine/meditation room. As indicated in the title, these are guidelines and they are meant to be just that, not dogmatic rules. First, a word about the actual altar itself. I use a small cherry wood end table, about one foot deep, two feet wide, and three feet high. It has a two shelves; an upper one designed with a slight angle for storing books, and a lower one which I use for storing candles and incense. I have draped over the top a silk brocade altar cloth, which helps keep incense ashes and candle wax off the table surface, and adds to its beauty. I got this table at a garage sale 25 years ago and have used it as an altar table ever since. Any similar sized table will serve nicely. Simple or fancy does not matter. Central to a shrine or altar is an image of the concept or deities one holds sacred. -

An Alternative Study of Chinese History: Two Daoist Temples

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2008 An alternative study of Chinese history: Two Daoist temples Joan Lorraine Mann University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Mann, Joan Lorraine, "An alternative study of Chinese history: Two Daoist temples" (2008). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2304. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/ryst-56ao This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ALTERNATIVE STUDY OF CHINESE HISTORY: TWO DAOIST TEMPLES by Joan Lorraine Mann Bachelor of Arts San Jose State University 1979 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Master of Arts Degree in History Department of History College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2008 UMI Number: 1456353 Copyright 2008 by Mann, Joan Lorraine All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

Modern Daoism 149 New Texts and Gods 150 Ritual Masters 152 Complete Perfection 154 Imperial Adaptations 157 an Expanded Pantheon 161

Contents Illustrations v Map of China vii Dynastic Chart viii Pronunciation Guide x Background to Daoism 1 Shang Ancestors and Divination 2 The Yijing 4 Ancient Philosophical Schools 8 Confucianism 10 Part I: Foundations 15 The Daoism That Can’t Be Told 16 The Text of the Daode Jing 17 The Dao 20 Creation and Decline 22 The Sage 23 Interpreting the Daode Jing 25 Lord Lao 28 Ritual Application 30 At Ease in Perfect Happiness 35 The Zhuangzi 36 The World of ZHuang ZHou 38 The Ideal Life 41 Poetic Adaptations 43 The Zen Connection 46 From Health to Immortality 50 i Body Energetics 51 Qi Cultivation 52 Healing Exercises 54 Magical Practitioners and Immortals 59 Major Schools of the Middle Ages 64 Celestial Masters 65 Highest Clarity 66 Numinous Treasure 68 The Theocracy 70 The Three Caverns 71 State Religion 74 Cosmos, Gods, and Governance 80 Yin and Yang 81 The Five Phases 82 The Chinese Calendar 85 Deities, Demons, and Divine Rulers 87 The Ideal of Great Peace 92 Cosmic Cycles 94 Part II: Development 96 Ethics and the Community 97 The Celestial Connection 98 Millenarian Structures 100 Self-Cultivation Groups 103 Lay Organizations 105 The Monastic Life 108 Creation and the Pantheon 114 Creation 115 Spells, Charts, and Talismans 118 Heavens and Hells 122 ii Gods, Ancestors, and Immortals 125 Religious Practices 130 Longevity Techniques 131 Breath and Sex 134 Forms of Meditation 136 Body Transformation 140 Ritual Activation 143 Part III: Modernity 148 Modern Daoism 149 New Texts and Gods 150 Ritual Masters 152 Complete Perfection 154 Imperial -

Shang Chu-Kuo Chiu-Min Tsung-Chen Pi-Yao (The Great One’S True Secret Essentials of Helping the Nation and Saving the People)

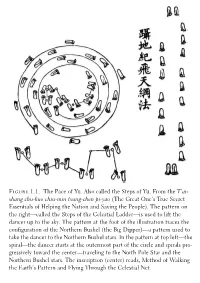

Shamanic Origins 13 Figure 1.1. The Pace of Yu¨. Also called the Steps of Yu¨. From the T’ai- shang chu-kuo chiu-min tsung-chen pi-yao (The Great One’s True Secret Essentials of Helping the Nation and Saving the People). The pattern on the right—called the Steps of the Celestial Ladder—is used to lift the dancer up to the sky. The pattern at the foot of the illustration traces the configuration of the Northern Bushel (the Big Dipper)—a pattern used to take the dancer to the Northern Bushel stars. In the pattern at top left—the spiral—the dancer starts at the outermost part of the circle and spirals pro- gressively toward the center—traveling to the North Pole Star and the Northern Bushel stars. The inscription (center) reads, Method of Walking the Earth’s Pattern and Flying Through the Celestial Net. ................. 5969$$ $CH1 12-15-10 09:17:26 PS PAGE 13 Transformation into Organized Religion 35 old Wu and Yu¨eh cultures that had survived even after these king- doms met their end in the late Spring and Autumn Period. Using talismanic water to heal the sick, Chang Tao-ling won a large following in Szechuan and the southern regions of China. Talis- manic water is water that contains the ashes of a talisman that was burned ceremonially. The talisman is a strip of yellow paper with a special script written on it in red (fig. 3.1). Most of the scripts are incantations or invocations of spirits and deities. This is how the power of the deity is channeled into the talisman. -

Researches Into Chinese Superstitions" Deals with the Form, Mode of Writing, and Explanation of Charms and Spells

INTO CHINESE SUPEHSTITIOXS By Henry Dore, S.J. TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH V li I WITH NOTES, HISTORICAL. AND EXPLANATORY By M. Kennelly, S.J. In First Part SUPERSTITIOUS PRACTICES Profusely illustrated Vol. Ill T'USEWEI PRINTING PRESS Shanghai 1916 \ Gettysburg College Library Gettysburg, Pa. RARE BOOK COLLECTION Gift of Dr. Frank H. Kramer Accession 10l|l|8U Shelf DS721.D72 v.3 <x lev ic INTO CHINESE SUPERSTITIONS By Henry Dore, S.J. TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH WITH NOTES, HISTORICAL AND EXPLANATORY By M. Kennelly, S.J. First Part SUPERSTITIOUS PRACTICES Profusely illustrated Vol. Ill T'USEWEI PRINTING PRESS Shanghai 191(7 PREFACE. This third volume of "Researches into Chinese Superstitions" deals with the form, mode of writing, and explanation of charms and spells. Completing- as it does the doctrine and popular notions contained in the two preceding volumes, it finds its natural and logical place here. In the French series, the Author published it as Volume V. This was owing to the difficulty he experienced in elucidating the abstruse principles, the mythical and phantastic inventions, the medley of Taoist and Buddhist philosophy which form the basis of charm writing. Taoism has influenced Confu- cianism. Kw'ei-sing $| jj|, the God of Literature, and as such worshipped by all students, is of Taoist origin. In pictures of him, he is represented as a demon-like personage, standing on one leg, and with the other kicking the Dipper, which is regarded as his palace. He holds in one hand an immense pencil, and in the other a cap for graduates (I). -

Part 5 Esoteric Contexts and Knowledge Transmission

Part 5 Esoteric Contexts and Knowledge Transmission Patrice Fava - 9789004366183 Downloaded from Brill.com10/11/2021 03:52:00AM via free access Patrice Fava - 9789004366183 Downloaded from Brill.com10/11/2021 03:52:00AM via free access 25 TheBodyofLaoziandtheCourseofaTaoistJourneyThroughtheHeavens Patrice Fava* At the border of Hunan and Jiangxi, where Taoist (Daoist) Lingbao taiji lianmi 靈寶太極鏈秘 (Alchemical Secrets rituals and the Nuo tradition of masked theatre have under- of the Supreme Ultimate Tradition of the Sacred Jewel) gone a large scale revival in recent decades, a Taoist master in the collection of Hunan Taoist Master Yi Songyao 易松 of the Orthodox Zhengyi 正一 sect, Master Yi Songyao 易 堯 of the Orthodox Zhengyi 正一 sect. According to an 松堯, has preserved a number of rare ancient paintings attribution on the cover, it had been in the possession of and manuscripts that have been transmitted to him as the Master He Huaide 何懷德 whose ordination name (luming liturgical texts of his lineage; these include a map of the 籙名) was Yuanzhen 元真. He copied it in the middle of body of Laozi and a chart of the course of a Taoist journey the 19th century from a manuscript by Zhang Fazheng through the Heavens. The following brief introduction to 張法正, who received the text himself in the 36th year these two documents serves mainly as an example of how of the Kangxi reign period (1697). The entire manuscript, an intimate knowledge of Taoist ritual can provide a key which includes some 70 double sheets, and contains many to the performative nature of the charts and indicates the texts, illustrations and diagrams related to Taoist ritual, rich scope for future research. -

THE MAGNITUDE of MING Command, Allotment, and Fate in Chinese Culture

TheMagnitudeofMing THE MAGNITUDE OF MING Command, Allotment, and Fate in Chinese Culture Edited by Christopher Lupke University of Hawai`i Press Honolulu ( 2005 University of Hawai`i Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 050607080910654321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The magnitude of ming : command, allotment, and fate in Chinese culture / edited by Christopher Lupke. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8248-2739-2 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Fate and fatalism. 2. Philosophy, Chinese. I. Lupke, Christopher. BJ1461.M34 2005 1230.0951Ðdc22 2004014194 Publication of this book has been assisted by a grant from the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange. University of Hawai`i Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources. Designed by University of Hawai`i Press production staff Printed by The Maple-Vail Book Manufacturing Group For My Mother, Clara Lupke Contents Preface ix Diverse Modes of Ming: An Introduction Christopher Lupke 1 Part I The Foundations of Fate Early Chinese Conceptions of Ming 1 Command and the Content of Tradition David Schaberg 23 2 Following the Commands of Heaven: The Notion of Ming in Early China Michael Puett 49 3 Languages of Fate: Semantic Fields in Chinese and Greek Lisa Raphals 70 4 How to Steer through Life: Negotiating Fate in the Daybook Mu-chou Poo 107 Part II Escape Attempts from Finitude Ming in the Later Han and Six Dynasties