Daoism in the Twentieth Century Between Eternity and Modernity Edited by David A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

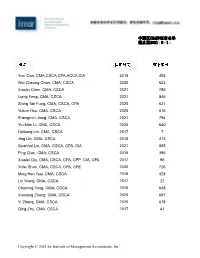

中国区cma持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日

中国区CMA持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日 Yixu Cao, CMA,CSCA,CPA,ACCA,CIA 2019 492 Wai Cheung Chan, CMA, CSCA 2020 622 Xiaolin Chen, CMA, CSCA 2021 785 Liang Feng, CMA, CSCA 2021 845 Shing Tak Fung, CMA, CSCA, CPA 2020 621 Yukun Hsu, CMA, CSCA 2020 676 Shengmin Jiang, CMA, CSCA 2021 794 Yiu Man Li, CMA, CSCA 2020 640 Huikang Lin, CMA, CSCA 2017 7 Jing Lin, CMA, CSCA 2018 415 Quanhui Liu, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CIA 2021 855 Ping Qian, CMA, CSCA 2018 396 Xiaolei Qiu, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CFP, CIA, CFA 2017 96 Yufei Shan, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CFE 2020 726 Ming Han Tsai, CMA, CSCA 2018 428 Lin Wang, CMA, CSCA 2017 22 Chunling Yang, CMA, CSCA 2020 648 Xiaolong Zhang, CMA, CSCA 2020 697 Yi Zhang, CMA, CSCA 2020 678 Qing Zhu, CMA, CSCA 2017 41 Copyright © 2021 by Institute of Management Accountants, Inc. 中国区CMA持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日 Siha A, CMA 2020 81134 Bei Ai, CMA 2020 84918 Danlu Ai, CMA 2021 94445 Fengting Ai, CMA 2019 75078 Huaqin Ai, CMA 2019 67498 Jie Ai, CMA 2021 94013 Jinmei Ai, CMA 2020 79690 Qingqing Ai, CMA 2019 67514 Weiran Ai, CMA 2021 99010 Xia Ai, CMA 2021 97218 Xiaowei Ai, CMA, CIA 2019 75739 Yizhan Ai, CMA 2021 92785 Zi Ai, CMA 2021 93990 Guanfei An, CMA 2021 99952 Haifeng An, CMA 2021 92781 Haixia An, CMA 2016 51078 Haiying An, CMA 2021 98016 Jie An, CMA 2012 38197 Jujie An, CMA 2018 58081 Jun An, CMA 2019 70068 Juntong An, CMA 2021 94474 Kewei An, CMA 2021 93137 Lanying An, CMA, CPA 2021 90699 Copyright © 2021 by Institute of Management Accountants, Inc. -

Performing Masculinity in Peri-Urban China: Duty, Family, Society

The London School of Economics and Political Science Performing Masculinity in Peri-Urban China: Duty, Family, Society Magdalena Wong A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London December 2016 1 DECLARATION I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/ PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 97,927 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help I confirm that different sections of my thesis were copy edited by Tiffany Wong, Emma Holland and Eona Bell for conventions of language, spelling and grammar. 2 ABSTRACT This thesis examines how a hegemonic ideal that I refer to as the ‘able-responsible man' dominates the discourse and performance of masculinity in the city of Nanchong in Southwest China. This ideal, which is at the core of the modern folk theory of masculinity in Nanchong, centres on notions of men's ability (nengli) and responsibility (zeren). -

Laozi Zhongjing)

A Study of the Central Scripture of Laozi (Laozi zhongjing) Alexandre Iliouchine A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts, Department of East Asian Studies McGill University January 2011 Copyright Alexandre Iliouchine © 2011 ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements......................................................................................... v Abstract/Résumé............................................................................................. vii Conventions and Abbreviations.................................................................... viii Introduction..................................................................................................... 1 On the Word ―Daoist‖............................................................................. 1 A Brief Introduction to the Central Scripture of Laozi........................... 3 Key Terms and Concepts: Jing, Qi, Shen and Xian................................ 5 The State of the Field.............................................................................. 9 The Aim of This Study............................................................................ 13 Chapter 1: Versions, Layers, Dates............................................................... 14 1.1 Versions............................................................................................. 15 1.1.1 The Transmitted Versions..................................................... 16 1.1.2 The Dunhuang Version........................................................ -

The Web That Has No Weaver

THE WEB THAT HAS NO WEAVER Understanding Chinese Medicine “The Web That Has No Weaver opens the great door of understanding to the profoundness of Chinese medicine.” —People’s Daily, Beijing, China “The Web That Has No Weaver with its manifold merits … is a successful introduction to Chinese medicine. We recommend it to our colleagues in China.” —Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China “Ted Kaptchuk’s book [has] something for practically everyone . Kaptchuk, himself an extraordinary combination of elements, is a thinker whose writing is more accessible than that of Joseph Needham or Manfred Porkert with no less scholarship. There is more here to think about, chew over, ponder or reflect upon than you are liable to find elsewhere. This may sound like a rave review: it is.” —Journal of Traditional Acupuncture “The Web That Has No Weaver is an encyclopedia of how to tell from the Eastern perspective ‘what is wrong.’” —Larry Dossey, author of Space, Time, and Medicine “Valuable as a compendium of traditional Chinese medical doctrine.” —Joseph Needham, author of Science and Civilization in China “The only approximation for authenticity is The Barefoot Doctor’s Manual, and this will take readers much further.” —The Kirkus Reviews “Kaptchuk has become a lyricist for the art of healing. And the more he tells us about traditional Chinese medicine, the more clearly we see the link between philosophy, art, and the physician’s craft.” —Houston Chronicle “Ted Kaptchuk’s book was inspirational in the development of my acupuncture practice and gave me a deep understanding of traditional Chinese medicine. -

The Cultural and Religious Background of Sexual Vampirism in Ancient China

Theology & Sexuality Volume 12(3): 285-308 Copyright © 2006 SAGE Publications London, Thousand Oaks CA, New Delhi http://TSE.sagepub.com DOI: 10.1177/1355835806065383 The Cultural and Religious Background of Sexual Vampirism in Ancient China Paul R. Goldin [email protected] Abstract This paper considers sexual macrobiotic techniques of ancient China in their cultural and religious milieu, focusing on the text known as Secret Instructions ofthe Jade Bedchamber, which explains how the Spirit Mother of the West, originally an ordinary human being like anyone else, devoured the life force of numerous young boys by copulating with them, and there- by transformed herself into a famed goddess. Although many previous studies of Chinese sexuality have highlighted such methods (the noted historian R.H. van Gulik was the first to refer to them as 'sexual vampirism'), it has rarely been asked why learned and intelligent people of the past took them seriously. The inquiry here, by considering some of the most common ancient criticisms of these practices, concludes that practitioners did not regard decay as an inescapable characteristic of matter; consequently it was widely believed that, if the cosmic processes were correctly under- stood, one could devise techniques that may forestall senectitude indefinitely. Keywords: sexual vampirism, macrobiotics, sex practices, Chinese religion, qi, Daoism Secret Instructions ofthe Jade Bedchamber {Yufang bijue S Ml^^) is a macro- biotic manual, aimed at men of leisure wealthy enough to own harems, outlining a regimen of sexual exercises that is supposed to confer immor- tality if practiced over a sufficient period. The original work is lost, but substantial fragments of it have been preserved in Ishimpo B'O:^, a Japanese chrestomathy of Chinese medical texts compiled by Tamba Yasuyori ^MMU (912-995) in 982. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/28/2021 09:41:18AM Via Free Access 102 M

Asian Medicine 7 (2012) 101–127 brill.com/asme Palpable Access to the Divine: Daoist Medieval Massage, Visualisation and Internal Sensation1 Michael Stanley-Baker Abstract This paper examines convergent discourses of cure, health and transcendence in fourth century Daoist scriptures. The therapeutic massages, inner awareness and visualisation practices described here are from a collection of revelations which became the founding documents for Shangqing (Upper Clarity) Daoism, one of the most influential sects of its time. Although formal theories organised these practices so that salvation superseded curing, in practice they were used together. This blending was achieved through a series of textual features and synæsthesic practices intended to address existential and bodily crises simultaneously. This paper shows how therapeutic inter- ests were fundamental to soteriology, and how salvation informed therapy, thus drawing atten- tion to the entanglements of religion and medicine in early medieval China. Keywords Massage, synæsthesia, visualisation, Daoism, body gods, soteriology The primary sources for this paper are the scriptures of the Shangqing 上清 (Upper Clarity), an early Daoist school which rose to prominence as the fam- ily religion of the imperial family. The soteriological goal was to join an elite class of divine being in the Shangqing heaven, the Perfected (zhen 真), who were superior to Transcendents (xianren 仙). Their teachings emerged at a watershed point in the development of Daoism, the indigenous religion of 1 I am grateful for the insightful criticisms and comments on draughts of this paper from Robert Campany, Jennifer Cash, Charles Chase, Terry Kleeman, Vivienne Lo, Johnathan Pettit, Pierce Salguero, and Nathan Sivin. -

Local Authority in the Han Dynasty: Focus on the Sanlao

Local Authority in the Han Dynasty: Focus on the Sanlao Jiandong CHEN 㱩ڎ暒 School of International Studies Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Technology Sydney Australia A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Technology Sydney Sydney, Australia 2018 Certificate of Original Authorship I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. This thesis is the result of a research candidature conducted with another University as part of a collaborative Doctoral degree. Production Note: Signature of Student: Signature removed prior to publication. Date: 30/10/2018 ii Acknowledgements The completion of the thesis would not have been possible without the help and support of many people. Firstly, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor, Associate Professor Jingqing Yang for his continuous support during my PhD study. Many thanks for providing me with the opportunity to study at the University of Technology Sydney. His patience, motivation and immense knowledge guided me throughout the time of my research. I cannot imagine having a better supervisor and mentor for my PhD study. Besides my supervisor, I would like to thank the rest of my thesis committee: Associate Professor Chongyi Feng and Associate Professor Shirley Chan, for their insightful comments and encouragement; and also for their challenging questions which incited me to widen my research and view things from various perspectives. -

Rostislav Berezkin Baojuan Publishing By

Rostislav Berezkin Baojuan publishing by Shanghai and Ningbo publishers (1911-1940) and its connection with the expansion and changes of the genre Abstract In the period between 1911 and 1940, a considerable number of baojuan (precious scrolls), the texts with primarily religious contents originally intended for oral presentation, was printed in Shanghai and nearby cities. Baojuan were often printed with the use of modern print technologies: lithographic and typeset press. The lithographic and typeset publishers specializing in baojuan printing appeared at that time. These publishers also were engaged in collecting and editing the baojuan texts as well as in retailing their print production. Looking at several cases of baojuan publishing, this paper explores the special features of this print production, especially in connection with the new trends in the work of publishers and the ways of consumption of baojuan editions. Due to the paucity of materials, the paper makes use mainly of the information in the original editions of baojuan which the author studied in collections of baojuan editions in several countries. 1 Introduction In the period between 1911 and 1940 several publishers in Shanghai and other cities of the Lower Yangtze region published numerous editions of baojuan (ਮ, precious scrolls). Baojuan are texts with primarily religious content originally intended for oral presentation. Baojuan is an old literary form that formed approximately in the 13 th -14 th centuries but still flourished at the beginning of the 20 th century. Scholars divide the history of baojuan into three periods. In the first one (ca. 13 th -15 th centuries), they propagated Buddhist doctrines. -

Religion in China BKGA 85 Religion Inchina and Bernhard Scheid Edited by Max Deeg Major Concepts and Minority Positions MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.)

Religions of foreign origin have shaped Chinese cultural history much stronger than generally assumed and continue to have impact on Chinese society in varying regional degrees. The essays collected in the present volume put a special emphasis on these “foreign” and less familiar aspects of Chinese religion. Apart from an introductory article on Daoism (the BKGA 85 BKGA Religion in China prototypical autochthonous religion of China), the volume reflects China’s encounter with religions of the so-called Western Regions, starting from the adoption of Indian Buddhism to early settlements of religious minorities from the Near East (Islam, Christianity, and Judaism) and the early modern debates between Confucians and Christian missionaries. Contemporary Major Concepts and religious minorities, their specific social problems, and their regional diversities are discussed in the cases of Abrahamitic traditions in China. The volume therefore contributes to our understanding of most recent and Minority Positions potentially violent religio-political phenomena such as, for instance, Islamist movements in the People’s Republic of China. Religion in China Religion ∙ Max DEEG is Professor of Buddhist Studies at the University of Cardiff. His research interests include in particular Buddhist narratives and their roles for the construction of identity in premodern Buddhist communities. Bernhard SCHEID is a senior research fellow at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. His research focuses on the history of Japanese religions and the interaction of Buddhism with local religions, in particular with Japanese Shintō. Max Deeg, Bernhard Scheid (eds.) Deeg, Max Bernhard ISBN 978-3-7001-7759-3 Edited by Max Deeg and Bernhard Scheid Printed and bound in the EU SBph 862 MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.) RELIGION IN CHINA: MAJOR CONCEPTS AND MINORITY POSITIONS ÖSTERREICHISCHE AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN PHILOSOPHISCH-HISTORISCHE KLASSE SITZUNGSBERICHTE, 862. -

Transmission of Han Pictorial Motifs Into the Western Periphery: Fuxi and Nüwa in the Wei-Jin Mural Tombs in the Hexi Corridor*8

DOI: 10.4312/as.2019.7.2.47-86 47 Transmission of Han Pictorial Motifs into the Western Periphery: Fuxi and Nüwa in the Wei-Jin Mural Tombs in the Hexi Corridor*8 ∗∗ Nataša VAMPELJ SUHADOLNIK 9 Abstract This paper examines the ways in which Fuxi and Nüwa were depicted inside the mu- ral tombs of the Wei-Jin dynasties along the Hexi Corridor as compared to their Han counterparts from the Central Plains. Pursuing typological, stylistic, and iconographic approaches, it investigates how the western periphery inherited the knowledge of the divine pair and further discusses the transition of the iconographic and stylistic design of both deities from the Han (206 BCE–220 CE) to the Wei and Western Jin dynasties (220–316). Furthermore, examining the origins of the migrants on the basis of historical records, it also attempts to discuss the possible regional connections and migration from different parts of the Chinese central territory to the western periphery. On the basis of these approaches, it reveals that the depiction of Fuxi and Nüwa in Gansu area was modelled on the Shandong regional pattern and further evolved into a unique pattern formed by an iconographic conglomeration of all attributes and other physical characteristics. Accordingly, the Shandong region style not only spread to surrounding areas in the central Chinese territory but even to the more remote border regions, where it became the model for funerary art motifs. Key Words: Fuxi, Nüwa, the sun, the moon, a try square, a pair of compasses, Han Dynasty, Wei-Jin period, Shandong, migration Prenos slikovnih motivov na zahodno periferijo: Fuxi in Nüwa v grobnicah s poslikavo iz obdobja Wei Jin na območju prehoda Hexi Izvleček Pričujoči prispevek v primerjalni perspektivi obravnava upodobitev Fuxija in Nüwe v grobnicah s poslikavo iz časa dinastij Wei in Zahodni Jin (220–316) iz province Gansu * The author acknowledges the financial support of the Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS) in the framework of the research core funding Asian languages and Cultures (P6-0243). -

Industrial Reform and Air Transport Development in China

INDUSTRIAL REFORM AND AIR TRANSPORT DEVELOPMENT IN CHINA Anming Zhang Department of Economics University of Victoria Victoria, BC Canada and Visiting Professor, 1996-98 Department of Economics and Finance City University of Hong Kong Hong Kong Occasional Paper #17 November 1997 Table of Contents Abstract ..................................................................... i Acknowledgements ............................................................ i I. INTRODUCTION .........................................................1 II. INDUSTRIAL REFORM ....................................................3 III. REFORMS IN THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY .....................................5 IV. AIR TRANSPORT DEVELOPMENT AND COMPETITION .......................7 A. Air Traffic Growth and Route Development ................................7 B. Market Structure and Route Concentration ................................10 C. Airline Operation and Competition ......................................13 V. CONCLUDING REMARKS ................................................16 References ..................................................................17 List of Tables Table 1: Model Split in Non-Urban Transport in China ................................2 Table 2: Traffic Volume in China's Airline Industry ...................................8 Table 3: Number of City-pair Routes in China's Airline Industry .........................8 Table 4: Overview of Chinese Airline Performance, 1980-94 ............................9 Table 5: Traffic Performed by China's Airlines -

The University of Chicago Practices of Scriptural Economy: Compiling and Copying a Seventh-Century Chinese Buddhist Anthology A

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRACTICES OF SCRIPTURAL ECONOMY: COMPILING AND COPYING A SEVENTH-CENTURY CHINESE BUDDHIST ANTHOLOGY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVINITY SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY ALEXANDER ONG HSU CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2018 © Copyright by Alexander Ong Hsu, 2018. All rights reserved. Dissertation Abstract: Practices of Scriptural Economy: Compiling and Copying a Seventh-Century Chinese Buddhist Anthology By Alexander Ong Hsu This dissertation reads a seventh-century Chinese Buddhist anthology to examine how medieval Chinese Buddhists practiced reducing and reorganizing their voluminous scriptural tra- dition into more useful formats. The anthology, A Grove of Pearls from the Garden of Dharma (Fayuan zhulin ), was compiled by a scholar-monk named Daoshi (?–683) from hundreds of Buddhist scriptures and other religious writings, listing thousands of quotations un- der a system of one-hundred category-chapters. This dissertation shows how A Grove of Pearls was designed by and for scriptural economy: it facilitated and was facilitated by traditions of categorizing, excerpting, and collecting units of scripture. Anthologies like A Grove of Pearls selectively copied the forms and contents of earlier Buddhist anthologies, catalogs, and other compilations; and, in turn, later Buddhists would selectively copy from it in order to spread the Buddhist dharma. I read anthologies not merely to describe their contents but to show what their compilers and copyists thought they were doing when they made and used them. A Grove of Pearls from the Garden of Dharma has often been read as an example of a Buddhist leishu , or “Chinese encyclopedia.” But the work’s precursors from the sixth cen- tury do not all fit neatly into this genre because they do not all use lei or categories consist- ently, nor do they all have encyclopedic breadth like A Grove of Pearls.