A Dictionary of Philosophy of Religion by Charles Taliaferro and Elsa J. Marty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Fukan As a Chinese Public Sphere: Zhang Dongsun and Learning Light

Journal of the Indiana Academy of the Social Sciences Volume 20 Issue 1 Article 6 2017 Building Fukan as a Chinese Public Sphere: Zhang Dongsun and Learning Light Nuan Gao Hanover College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jiass Recommended Citation Gao, Nuan (2017) "Building Fukan as a Chinese Public Sphere: Zhang Dongsun and Learning Light," Journal of the Indiana Academy of the Social Sciences: Vol. 20 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jiass/vol20/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Indiana Academy of the Social Sciences by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Building Fukan as a Chinese Public Sphere: Zhang Dongsun and Learning Light* NUAN GAO Hanover College ABSTRACT This article attempts to explore the relevance of the public sphere, conceptualized by Jürgen Habermas, in the Chinese context. The author focuses on the case of Learning Light (Xuedeng), one of the most reputable fukans, or newspaper supplements, of the May Fourth era (1915–1926), arguing that fukan served a very Habermasian function, in terms of its independence from power intervention and its inclusiveness of incorporating voices across political and social strata. Through examining the leadership of Zhang Dongsun, editor in chief of Learning Light, as well as the public opinions published in this fukan, the author also discovers that, in constructing China’s public sphere, both the left and moderate intellectuals of the May Fourth era used conscious effort and shared the same moral courage, although their roles were quite different: The left was more prominent as passionate and idealist spiritual leaders shining in the center of the historic stage, whereas in comparison, the moderates acted as pragmatic and rational organizers, ensuring a benevolent environment for the stage. -

Schelling's Naturalism: Motion, Space, and the Volition of Thought

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholarship@Western Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-23-2015 12:00 AM Schelling's Naturalism: Motion, Space, and the Volition of Thought Ben Woodard The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Tilottama Rajan The University of Western Ontario Joint Supervisor Joan Steigerwald The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Theory and Criticism A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Ben Woodard 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the History of Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Woodard, Ben, "Schelling's Naturalism: Motion, Space, and the Volition of Thought" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3314. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3314 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Schelling's Naturalism: Motion, Space, and the Volition of Thought (Thesis Format: Monograph) by Benjamin Graham Woodard A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy in Theory and Criticism The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Ben Woodard 2015 Abstract: This dissertation examines F.W.J. von Schelling's Philosophy of Nature (or Naturphilosophie) as a form of early, and transcendentally expansive, naturalism that is, simultaneously, a naturalized transcendentalism. -

SACRED SPACES and OBJECTS: the VISUAL, MATERIAL, and TANGIBLE George Pati

SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART | APRIL 13 — MAY 8, 2016 WE AT THE BRAUER MUSEUM are grateful for the opportunity to present this exhibition curated by George Pati, Ph.D., Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and Valparaiso University associate professor of theology and international studies. Through this exhibition, Professor Pati shares the fruits of his research conducted during his recent sabbatical and in addition provides valuable insights into sacred objects, sites, and practices in India. Professor Pati’s photographs document specific places but also reflect a creative eye at work; as an artist, his documents are also celebrations of the particular spaces that inspire him and capture his imagination. Accompanying the images in the exhibition are beautiful textiles and objects of metalware that transform the gallery into its own sacred space, with respectful and reverent viewing becoming its own ritual that could lead to a fuller understanding of the concepts Pati brings to our attention. Professor Pati and the Brauer staff wish to thank the Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and the Partners for the Brauer Museum of Art for support of this exhibition. In addition, we wish to thank Gretchen Buggeln and David Morgan for the insights and perspectives they provide in their responses to Pati's essay and photographs. Gregg Hertzlieb, Director/Curator Brauer Museum of Art 2 | BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati George Pati, Ph.D., Valparaiso University Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad 6:23 Only in a man who has utmost devotion for God, and who shows the same devotion for teacher as for God, These teachings by the noble one will be illuminating. -

A Study of the Early Vedic Age in Ancient India

Journal of Arts and Culture ISSN: 0976-9862 & E-ISSN: 0976-9870, Volume 3, Issue 3, 2012, pp.-129-132. Available online at http://www.bioinfo.in/contents.php?id=53. A STUDY OF THE EARLY VEDIC AGE IN ANCIENT INDIA FASALE M.K.* Department of Histroy, Abasaheb Kakade Arts College, Bodhegaon, Shevgaon- 414 502, MS, India *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: December 04, 2012; Accepted: December 20, 2012 Abstract- The Vedic period (or Vedic age) was a period in history during which the Vedas, the oldest scriptures of Hinduism, were composed. The time span of the period is uncertain. Philological and linguistic evidence indicates that the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas, was com- posed roughly between 1700 and 1100 BCE, also referred to as the early Vedic period. The end of the period is commonly estimated to have occurred about 500 BCE, and 150 BCE has been suggested as a terminus ante quem for all Vedic Sanskrit literature. Transmission of texts in the Vedic period was by oral tradition alone, and a literary tradition set in only in post-Vedic times. Despite the difficulties in dating the period, the Vedas can safely be assumed to be several thousands of years old. The associated culture, sometimes referred to as Vedic civilization, was probably centred early on in the northern and northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent, but has now spread and constitutes the basis of contemporary Indian culture. After the end of the Vedic period, the Mahajanapadas period in turn gave way to the Maurya Empire (from ca. -

What's Wrong with the Study of China/Countries

Asian Studies II (XVIII), 1 (2014), pp. 151–185 What’s Wrong with the Study of China/Countries Hans KUIJPER* Abstract In this paper 1 the thesis is submitted that there is something fundamentally amiss in Western Sinology (Zhōngguóxué, as distinct from Hànxué, which is a kind of old- fashioned philology): ‘China experts’ either pretend to be knowledgeable about everything related to China, in which case they cannot be taken seriously, or–– eventually––admit not to be scientific all-rounders with respect to the country, in which case they cannot be called ‘China experts’. The author expects no tenured professor of Chinese Studies/History to share this view. Having exposed the weakness, indeed the scandal of old-style Sinology, he also points out the way junior Sinologists should go. The fork in that road is two-pronged: translating or collaborating. Keywords: Sinology, area/country studies, complexity, scientific collaboration, e-research Izvleček V tem članku avtor predstavi tezo, da je nekaj bistveno narobe v zahodni sinologiji (Zhōngguóxué, za razliko od Hànxué, ki je nekakšna staromodna filologija): »Kitajski strokovnjaki« se bodisi pretvarjajo, da so dobro obveščeni o vsem v zvezi s Kitajsko, in v tem primeru jih ni mogoče jemati resno, ali pa na koncu priznajo, da niso vsestransko znanstveni o državi, in jih v tem primeru ne moremo imenovati »Kitajske strokovnjake«. Avtor pričakuje, da nihče od univerzitetnih profesorjev kitajskih študij ali kitajske zgodovine ne deli tega stališča z njim. Z izpostavljenostjo šibkosti, kar je škandal za sinologijo starega sloga, opozarja tudi na pot, po kateri naj bi šli mladi sinologi. Na tej poti sta dve smeri, in sicer prevajanje ali sodelovanje. -

The Golden Cord

THE GOLDEN CORD A SHORT BOOK ON THE SECULAR AND THE SACRED ' " ' ..I ~·/ I _,., ' '4 ~ 'V . \ . " ': ,., .:._ C HARLE S TALIAFERR O THE GOLDEN CORD THE GOLDEN CORD A SHORT BOOK ON THE SECULAR AND THE SACRED CHARLES TALIAFERRO University of Notre Dame Press Notre Dame, Indiana Copyright © 2012 by the University of Notre Dame Press Notre Dame, Indiana 46556 www.undpress.nd.edu All Rights Reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Taliaferro, Charles. The golden cord : a short book on the secular and the sacred / Charles Taliaferro. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-268-04238-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-268-04238-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. God (Christianity) 2. Life—Religious aspects—Christianity. 3. Self—Religious aspects—Christianity. 4. Redemption—Christianity. 5. Cambridge Platonism. I. Title. BT103.T35 2012 230—dc23 2012037000 ∞ The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 CHAPTER 1 Love in the Physical World 15 CHAPTER 2 Selves and Bodies 41 CHAPTER 3 Some Big Pictures 61 CHAPTER 4 Some Real Appearances 81 CHAPTER 5 Is God Mad, Bad, and Dangerous to Know? 107 CHAPTER 6 Redemption and Time 131 CHAPTER 7 Eternity in Time 145 CHAPTER 8 Glory and the Hallowing of Domestic Virtue 163 Notes 179 Index 197 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply grateful for the patience, graciousness, support, and encour- agement of the University of Notre Dame Press’s senior editor, Charles Van Hof. -

Defining Man As Animal Religiosum in English Religious Writing C. 1650–C

Accepted for publication in Church History for publication in September 2019. Title: Defining Man as Animal Religiosum in English Religious Writing c. 1650–c. 1700 Abstract: This article surveys the emergence and usage of the redefinition of man not as animal rationale (a rational animal) but as animal religiosum (a religious animal) by numerous English theologians between 1650 and 1700. Across the continuum of English protestant thought human nature was being re-described as unique due to its religious, not primarily its rational, capabilities. The article charts this appearance as a contribution to debates over man’s relationship with God; then its subsequent incorporation into the subsequent debate over the theological consequences of arguments in favor of animal rationality, as well as its uses in anti-atheist apologetics; and then the sudden disappearance of the definition of man as animal religiosum at the beginning of the eighteenth century. In doing so, the article hopes to make a useful contribution to our understanding of changing early modern understandings of human nature by reasserting the significance of theological debates within the context of seventeenth-century debate about the relationship between humans and beasts and by offering a more wide-ranging account of man as animal religiosum than the current focus on ‘Cambridge Platonism’ and ‘Latitudinarianism’ allows. Keywords: Animal rationality, reason, 17th c. England, Cambridge Platonism, Latitudinarianism. Contact Details: Dr R J W Mills Dept. of History, University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT United Kingdom [email protected] 1 Accepted for publication in Church History for publication in September 2019. -

The Ideal Observer Theory and Motivational Internalism

The Ideal Observer Theory and Motivational Internalism Daniel Ronnedal¨ Abstract In this paper I show that one version of motivational internalism follows from the so-called ideal observer theory. Let us call the version of the ideal observer theory used in this essay (IOT). According to (IOT), it is necessarily the case that it ought to be that A if and only if every ideal observer wants it to be the case that A. We shall call the version of motivational internalism that follows from (IOT) (moral) conditional belief motivational internalism (CBMI). According to (CBMI), it is necessarily the case that, for every x: if x were an ideal observer, it would be the case that x believes that it ought to be that A only if x wants it to be the case that A. Given that it is necessarily true that no ideal observer has any false beliefs, (IOT) entails (CBMI). Or, so I shall argue. Keywords: the ideal observer theory, motivational internalism, practical reason 1 Introduction In this paper I show that one version of motivational internalism follows from the so-called ideal observer theory. The classical modern formula- tion of the ideal observer theory is [16].1 According to Roderick Firth, If it is possible to formulate a satisfactory absolutist and dis- positional analysis of ethical statements, it must be possible [. ] to express the meaning of statements of the form \x is right" in terms of other statements which have the form: \Any ideal observer would react to x in such and such a way under such and such conditions." [16, 329] The main idea seems to be that an act is right if and only if (iff) it would be approved by any ideal observer, and more generally that an act has Kriterion { Journal of Philosophy, 2015, 29(1): 79{98. -

A Fundamental Problem for Skeptical Theism

A fundamental problem for skeptical theism Atle O. Søvik Det teologiske menighetsfakultet Postboks 5144 Majorstuen 0302 Oslo [email protected] Abstract: The argument from divine hiddenness says that since probably there is pointless divine hiding, then probably God does not exist. Francis Jonbäck argues that a good response to this argument is to deny that one can assign a probability value to the claim that there is pointless divine hiding. I argue in this article the opposite, and that we should instead choose a theodicy response. Keywords: Skeptical theism; divine hiddenness; value agnosticism; Francis Jonbäck; theodicy Introduction Skeptical theism is acknowledged by many as a good response to the problem of evil and the argument from divine hiddenness.1 Simply put, the problem of evil is that we would expect the world to be better given that there is a good and omnipotent God, while the argument from divine hiddenness is that we would expect to have more evidence of the existence of God given that there is a good and omnipotent God. Skeptical theism responds to these arguments by challenging the idea of what we have reason to expect. God may have good reasons for allowing evil or hiding which we have no reason to think that we should know, and thus these arguments are not good arguments against the existence of God, according to skeptical theism. In a recent clearly written and well structured book, Francis Jonbäck presents a defense of what he calls value agnosticism as a response to the argument from divine hiddenness.2 Value agnosticism says that we are not is a position to estimate how probable or not it is that God has good reasons for hiding. -

The Problem of Evil As a Moral Objection to Theism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository THE PROBLEM OF EVIL AS A MORAL OBJECTION TO THEISM by TOBY GEORGE BETENSON A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY. Department of Philosophy School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract: I argue that the problem of evil can be a moral objection to theistic belief. The thesis has three broad sections, each establishing an element in this argument. Section one establishes the logically binding nature of the problem of evil: The problem of evil must be solved, if you are to believe in God. And yet, I borrow from J. L. Mackie’s criticisms of the moral argument for the existence of God, and argue that the fundamentally evaluative nature of the premises within the problem of evil entails that it cannot be used to argue for the non- existence of God. -

The Argument from Logical Principles Against Materialism: a Version of the Argument from Reason

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2019-04-30 The Argument from Logical Principles Against Materialism: A Version of the Argument from Reason Hawkes, Gordon Hawkes, G. (2019). The Argument from Logical Principles Against Materialism: A Version of the Argument from Reason (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/110301 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Argument from Logical Principles Against Materialism: A Version of the Argument from Reason by Gordon Hawkes A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN PHILOSOPHY CALGARY, ALBERTA APRIL, 2019 © Gordon Hawkes 2019 i Abstract The argument from reason is the name given to a family of arguments against naturalism, materialism, or determinism, and often for theism or dualism. One version of the argument from reason is what Victor Reppert calls “the argument from the psychological relevance of logical laws,” or what I call “the argument from logical principles.” This argument has received little attention in the literature, despite being advanced by Victor Reppert, Karl Popper, and Thomas Nagel. -

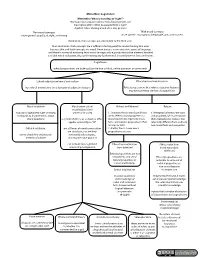

Ethical Realism/Moral Realism Ethical Propositions That Refer to Objective Features May Be True If They Are Free of Subjectivis

Metaethics: Cognitivism Metaethics: What is morality, or “right”? Normative (prescriptive) ethics: How should people act? Descriptive ethics: What do people think is right? Applied ethics: Putting moral ideas into practice Thin moral concepts Thick moral concepts more general: good, bad, right, and wrong more specic: courageous, inequitable, just, or dishonest Centralism- thin concepts are antecedent to the thick ones Non-centralism- thick concepts are a sucient starting point for understanding thin ones because thin and thick concepts are equal. Normativity is a non-excisable aspect of language and there is no way of analyzing thick moral concepts into a purely descriptive element attached to a thin moral evaluation, thus undermining any fundamental division between facts and norms. Cognitivism ethical propositions are truth-apt (can be true or false), unlike questions or commands Ethical subjectivism/moral anti-realism Ethical realism/moral realism True ethical propositions are a function of subjective features Ethical propositions that refer to objective features may be true if they are free of subjectivism Moral relativism Moral universalism/ Robust and Minimal Robust moral objectivism/ nobody is objectively right or wrong universal morality 1. Semantic thesis: moral predicates 3. Metaphysical thesis: the facts in regards to diagreements about are to refer to moral properties so and properties of #1 are robust-- moral questions a system of ethics, or a universal ethic, moral statements represent moral their metaphysical status is not applies universally to "all" facts, and express propositions that relevantly dierent from ordinary are true or false non-moral facts and properties Cultural relativism not all forms of moral universalism 2.