China Perspectives, 55 | September - October 2004 the Debate Between Liberalism and Neo-Leftism at the Turn of the Century 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Fukan As a Chinese Public Sphere: Zhang Dongsun and Learning Light

Journal of the Indiana Academy of the Social Sciences Volume 20 Issue 1 Article 6 2017 Building Fukan as a Chinese Public Sphere: Zhang Dongsun and Learning Light Nuan Gao Hanover College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jiass Recommended Citation Gao, Nuan (2017) "Building Fukan as a Chinese Public Sphere: Zhang Dongsun and Learning Light," Journal of the Indiana Academy of the Social Sciences: Vol. 20 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jiass/vol20/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Indiana Academy of the Social Sciences by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Building Fukan as a Chinese Public Sphere: Zhang Dongsun and Learning Light* NUAN GAO Hanover College ABSTRACT This article attempts to explore the relevance of the public sphere, conceptualized by Jürgen Habermas, in the Chinese context. The author focuses on the case of Learning Light (Xuedeng), one of the most reputable fukans, or newspaper supplements, of the May Fourth era (1915–1926), arguing that fukan served a very Habermasian function, in terms of its independence from power intervention and its inclusiveness of incorporating voices across political and social strata. Through examining the leadership of Zhang Dongsun, editor in chief of Learning Light, as well as the public opinions published in this fukan, the author also discovers that, in constructing China’s public sphere, both the left and moderate intellectuals of the May Fourth era used conscious effort and shared the same moral courage, although their roles were quite different: The left was more prominent as passionate and idealist spiritual leaders shining in the center of the historic stage, whereas in comparison, the moderates acted as pragmatic and rational organizers, ensuring a benevolent environment for the stage. -

The Web That Has No Weaver

THE WEB THAT HAS NO WEAVER Understanding Chinese Medicine “The Web That Has No Weaver opens the great door of understanding to the profoundness of Chinese medicine.” —People’s Daily, Beijing, China “The Web That Has No Weaver with its manifold merits … is a successful introduction to Chinese medicine. We recommend it to our colleagues in China.” —Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China “Ted Kaptchuk’s book [has] something for practically everyone . Kaptchuk, himself an extraordinary combination of elements, is a thinker whose writing is more accessible than that of Joseph Needham or Manfred Porkert with no less scholarship. There is more here to think about, chew over, ponder or reflect upon than you are liable to find elsewhere. This may sound like a rave review: it is.” —Journal of Traditional Acupuncture “The Web That Has No Weaver is an encyclopedia of how to tell from the Eastern perspective ‘what is wrong.’” —Larry Dossey, author of Space, Time, and Medicine “Valuable as a compendium of traditional Chinese medical doctrine.” —Joseph Needham, author of Science and Civilization in China “The only approximation for authenticity is The Barefoot Doctor’s Manual, and this will take readers much further.” —The Kirkus Reviews “Kaptchuk has become a lyricist for the art of healing. And the more he tells us about traditional Chinese medicine, the more clearly we see the link between philosophy, art, and the physician’s craft.” —Houston Chronicle “Ted Kaptchuk’s book was inspirational in the development of my acupuncture practice and gave me a deep understanding of traditional Chinese medicine. -

What's Wrong with the Study of China/Countries

Asian Studies II (XVIII), 1 (2014), pp. 151–185 What’s Wrong with the Study of China/Countries Hans KUIJPER* Abstract In this paper 1 the thesis is submitted that there is something fundamentally amiss in Western Sinology (Zhōngguóxué, as distinct from Hànxué, which is a kind of old- fashioned philology): ‘China experts’ either pretend to be knowledgeable about everything related to China, in which case they cannot be taken seriously, or–– eventually––admit not to be scientific all-rounders with respect to the country, in which case they cannot be called ‘China experts’. The author expects no tenured professor of Chinese Studies/History to share this view. Having exposed the weakness, indeed the scandal of old-style Sinology, he also points out the way junior Sinologists should go. The fork in that road is two-pronged: translating or collaborating. Keywords: Sinology, area/country studies, complexity, scientific collaboration, e-research Izvleček V tem članku avtor predstavi tezo, da je nekaj bistveno narobe v zahodni sinologiji (Zhōngguóxué, za razliko od Hànxué, ki je nekakšna staromodna filologija): »Kitajski strokovnjaki« se bodisi pretvarjajo, da so dobro obveščeni o vsem v zvezi s Kitajsko, in v tem primeru jih ni mogoče jemati resno, ali pa na koncu priznajo, da niso vsestransko znanstveni o državi, in jih v tem primeru ne moremo imenovati »Kitajske strokovnjake«. Avtor pričakuje, da nihče od univerzitetnih profesorjev kitajskih študij ali kitajske zgodovine ne deli tega stališča z njim. Z izpostavljenostjo šibkosti, kar je škandal za sinologijo starega sloga, opozarja tudi na pot, po kateri naj bi šli mladi sinologi. Na tej poti sta dve smeri, in sicer prevajanje ali sodelovanje. -

Twenty-Four Conservative-Liberal Thinkers Part I Hannes H

Hannes H. Gissurarson Twenty-Four Conservative-Liberal Thinkers Part I Hannes H. Gissurarson Twenty-Four Conservative-Liberal Thinkers Part I New Direction MMXX CONTENTS Hannes H. Gissurarson is Professor of Politics at the University of Iceland and Director of Research at RNH, the Icelandic Research Centre for Innovation and Economic Growth. The author of several books in Icelandic, English and Swedish, he has been on the governing boards of the Central Bank of Iceland and the Mont Pelerin Society and a Visiting Scholar at Stanford, UCLA, LUISS, George Mason and other universities. He holds a D.Phil. in Politics from Oxford University and a B.A. and an M.A. in History and Philosophy from the University of Iceland. Introduction 7 Snorri Sturluson (1179–1241) 13 St. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) 35 John Locke (1632–1704) 57 David Hume (1711–1776) 83 Adam Smith (1723–1790) 103 Edmund Burke (1729–1797) 129 Founded by Margaret Thatcher in 2009 as the intellectual Anders Chydenius (1729–1803) 163 hub of European Conservatism, New Direction has established academic networks across Europe and research Benjamin Constant (1767–1830) 185 partnerships throughout the world. Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850) 215 Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–1859) 243 Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) 281 New Direction is registered in Belgium as a not-for-profit organisation and is partly funded by the European Parliament. Registered Office: Rue du Trône, 4, 1000 Brussels, Belgium President: Tomasz Poręba MEP Executive Director: Witold de Chevilly Lord Acton (1834–1902) 313 The European Parliament and New Direction assume no responsibility for the opinions expressed in this publication. -

Local Authority in the Han Dynasty: Focus on the Sanlao

Local Authority in the Han Dynasty: Focus on the Sanlao Jiandong CHEN 㱩ڎ暒 School of International Studies Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Technology Sydney Australia A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Technology Sydney Sydney, Australia 2018 Certificate of Original Authorship I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. This thesis is the result of a research candidature conducted with another University as part of a collaborative Doctoral degree. Production Note: Signature of Student: Signature removed prior to publication. Date: 30/10/2018 ii Acknowledgements The completion of the thesis would not have been possible without the help and support of many people. Firstly, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor, Associate Professor Jingqing Yang for his continuous support during my PhD study. Many thanks for providing me with the opportunity to study at the University of Technology Sydney. His patience, motivation and immense knowledge guided me throughout the time of my research. I cannot imagine having a better supervisor and mentor for my PhD study. Besides my supervisor, I would like to thank the rest of my thesis committee: Associate Professor Chongyi Feng and Associate Professor Shirley Chan, for their insightful comments and encouragement; and also for their challenging questions which incited me to widen my research and view things from various perspectives. -

Brazilian Images of the United States, 1861-1898: a Working Version of Modernity?

Brazilian images of the United States, 1861-1898: A working version of modernity? Natalia Bas University College London PhD thesis I, Natalia Bas, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Abstract For most of the nineteenth-century, the Brazilian liberal elites found in the ‘modernity’ of the European Enlightenment all that they considered best at the time. Britain and France, in particular, provided them with the paradigms of a modern civilisation. This thesis, however, challenges and complements this view by demonstrating that as early as the 1860s the United States began to emerge as a new model of civilisation in the Brazilian debate about modernisation. The general picture portrayed by the historiography of nineteenth-century Brazil is still today inclined to overlook the meaningful place that U.S. society had from as early as the 1860s in the Brazilian imagination regarding the concept of a modern society. This thesis shows how the images of the United States were a pivotal source of political and cultural inspiration for the political and intellectual elites of the second half of the nineteenth century concerned with the modernisation of Brazil. Drawing primarily on parliamentary debates, newspaper articles, diplomatic correspondence, books, student journals and textual and pictorial advertisements in newspapers, this dissertation analyses four different dimensions of the Brazilian representations of the United States. They are: the abolition of slavery, political and civil freedoms, democratic access to scientific and applied education, and democratic access to goods of consumption. -

The Case of Zhang Yiwu

ASIA 2016; 70(3): 921–941 Giorgio Strafella* Postmodernism as a Nationalist Conservatism? The Case of Zhang Yiwu DOI 10.1515/asia-2015-1014 Abstract: The adoption of postmodernist and postcolonial theories by China’s intellectuals dates back to the early 1990s and its history is intertwined with that of two contemporaneous trends in the intellectual sphere, i. e. the rise of con- servatism and an effort to re-define the function of the Humanities in the country. This article examines how these trends merge in the political stance of a key figure in that process, Peking University literary scholar Zhang Yiwu, through a critical discourse analysis of his writings from the early and mid- 1990s. Pointing at his strategic use of postmodernist discourse, it argues that Zhang Yiwu employed a legitimate critique of the concept of modernity and West-centrism to advocate a historical narrative and a definition of cultural criticism that combine Sino-centrism and depoliticisation. The article examines programmatic articles in which the scholar articulated a theory of the end of China’s “modernity”. It also takes into consideration other parallel interventions that shed light on Zhang Yiwu’s political stance towards modern China, globalisation and post-1992 economic reforms, including a discussion between Zhang Yiwu and some of his most prominent detractors. The article finally reflects on the implications of Zhang Yiwu’s writings for the field of Chinese Studies, in particular on the need to look critically and contextually at the adoption of “foreign” theoretical discourse for national political agendas. Keywords: China, intellectuals, postmodernism, Zhang Yiwu, conservatism, nationalism 1 Introduction This article looks at the early history and politics of the appropriation of post- modernist discourse in the Chinese intellectual sphere, thus addressing the plurality of postmodernity via the plurality of postmodernism. -

The Danger of Deconsolidation Roberto Stefan Foa and Yascha Mounk Ronald F

July 2016, Volume 27, Number 3 $14.00 The Danger of Deconsolidation Roberto Stefan Foa and Yascha Mounk Ronald F. Inglehart The Struggle Over Term Limits in Africa Brett L. Carter Janette Yarwood Filip Reyntjens 25 Years After the USSR: What’s Gone Wrong? Henry E. Hale Suisheng Zhao on Xi Jinping’s Maoist Revival Bojan Bugari¡c & Tom Ginsburg on Postcommunist Courts Clive H. Church & Adrian Vatter on Switzerland Daniel O’Maley on the Internet of Things Delegative Democracy Revisited Santiago Anria Catherine Conaghan Frances Hagopian Lindsay Mayka Juan Pablo Luna Alberto Vergara and Aaron Watanabe Zhao.NEW saved by BK on 1/5/16; 6,145 words, including notes; TXT created from NEW by PJC, 3/18/16; MP edits to TXT by PJC, 4/5/16 (6,615 words). AAS saved by BK on 4/7/16; FIN created from AAS by PJC, 4/25/16 (6,608 words). PGS created by BK on 5/10/16. XI JINPING’S MAOIST REVIVAL Suisheng Zhao Suisheng Zhao is professor at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver. He is executive director of the univer- sity’s Center for China-U.S. Cooperation and editor of the Journal of Contemporary China. When Xi Jinping became paramount leader of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 2012, some Chinese intellectuals with liberal lean- ings allowed themselves to hope that he would promote the cause of political reform. The most optimistic among them even thought that he might seek to limit the monopoly on power long claimed by the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP). -

Governance and Politics of China

Copyrighted material – 978–1–137–44527–8 © Tony Saich 2001, 2004, 2011, 2015 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identifi ed as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First edition 2001 Second edition 2004 Third edition 2011 Fourth edition 2015 Published by PALGRAVE Palgrave in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of 4 Crinan Street, London, N1 9XW. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave is a global imprint of the above companies and is represented throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978–1–137–44528–5 hardback ISBN 978–1–137–44527–8 paperback This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. -

Issue 1 2013

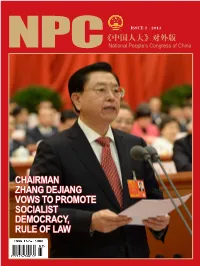

ISSUE 1 · 2013 NPC《中国人大》对外版 CHAIRMAN ZHANG DEJIANG VOWS TO PROMOTE SOCIALIST DEMOCRACY, RULE OF LAW ISSUE 4 · 2012 1 Chairman of the NPC Standing Committee Zhang Dejiang (7th, L) has a group photo with vice-chairpersons Zhang Baowen, Arken Imirbaki, Zhang Ping, Shen Yueyue, Yan Junqi, Wang Shengjun, Li Jianguo, Chen Changzhi, Wang Chen, Ji Bingxuan, Qiangba Puncog, Wan Exiang, Chen Zhu (from left to right). Ma Zengke China’s new leadership takes 6 shape amid high expectations Contents Special Report Speech In–depth 6 18 24 China’s new leadership takes shape President Xi Jinping vows to bring China capable of sustaining economic amid high expectations benefits to people in realizing growth: Premier ‘Chinese dream’ 8 25 Chinese top legislature has younger 19 China rolls out plan to transform leaders Chairman Zhang Dejiang vows government functions to promote socialist democracy, 12 rule of law 27 China unveils new cabinet amid China’s anti-graft efforts to get function reform People institutional impetus 15 20 28 Report on the work of the Standing Chairman Zhang Dejiang: ‘Power China defense budget to grow 10.7 Committee of the National People’s should not be aloof from public percent in 2013 Congress (excerpt) supervision’ 20 Chairman Zhang Dejiang: ‘Power should not be aloof from public supervision’ Doubling income is easy, narrowing 30 regional gap is anything but 34 New age for China’s women deputies ISSUE 1 · 2013 29 37 Rural reform helps China ensure grain Style changes take center stage at security Beijing’s political season 30 Doubling -

Confucianism, "Cultural Tradition" and Official Discourses in China at the Start of the New Century

China Perspectives 2007/3 | 2007 Creating a Harmonious Society Confucianism, "cultural tradition" and official discourses in China at the start of the new century Sébastien Billioud Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/2033 DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.2033 ISSN : 1996-4617 Éditeur Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 septembre 2007 ISSN : 2070-3449 Référence électronique Sébastien Billioud, « Confucianism, "cultural tradition" and official discourses in China at the start of the new century », China Perspectives [En ligne], 2007/3 | 2007, mis en ligne le 01 septembre 2010, consulté le 14 novembre 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/2033 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.2033 © All rights reserved Special feature s e v Confucianism, “Cultural i a t c n i e Tradition,” and Official h p s c r Discourse in China at the e p Start of the New Century SÉBASTIEN BILLIOUD This article explores the reference to traditional culture and Confucianism in official discourses at the start of the new century. It shows the complexity and the ambiguity of the phenomenon and attempts to analyze it within the broader framework of society’s evolving relation to culture. armony (hexie 和谐 ), the rule of virtue ( yi into allusions made in official discourse, we are interested de zhi guo 以德治国 ): for the last few years in another general and imprecise category: cultural tradi - Hthe consonance suggested by slogans and tion ( wenhua chuantong ) or traditional cul - 文化传统 themes mobilised by China’s leadership has led to spec - ture ( chuantong wenhua 传统文化 ). ((1) However, we ulation concerning their relationship to Confucianism or, are excluding from the domain of this study the entire as - more generally, to China’s classical cultural tradition. -

An Interdisciplinary Journal on Greater China

The China Review An Interdisciplinary Journal on Greater China Volume 14 Number 2 Fall 2014 Special Issue Doing Sinology in Former Socialist States, Reflections from the Czech Republic, Mongolia, Poland, and Russia: Introduction Chih-yu Shih (Guest Editor) Beyond Academia and Politics: Understanding China and Doing Sinology in Czechoslovakia after World War II Olga Lomová and Anna Zádrapová Surging between China and Russia: Legacies, Politics, and Turns of Sinology in Contemporary Mongolia Enkhchimeg Baatarkhuyag and Chih-yu Shih Volume 14 Number 2 Fall 2014 The Study of China in Poland after World War II: Toward the “New Sinology”? Anna Rudakowska The Lifting of the “Iron Veil” by Russian Sinologists During the Soviet Period (1917–1991) Materials Valentin C. Golovachev Soviet Sinology and Two Approaches to an Understanding of Chinese History An Interdisciplinary Alexander Pisarev Uneven Development vs. Searching for Integrity: Chinese Studies in Post-Soviet Russia Journal on Alexei D. Voskressenski Copyrighted Do We Need to Rethink Sinology? Views from the Eastern Bloc Fabio Lanza Press: Greater China Other Articles Professional Commitment and Job Satisfaction: An Analysis of the Chinese Judicial Reforms from the Perspective of the Criminal Defense University Hong Lu, Bin Liang, Yudu Li, and Ni (Phil) He The Discourse of Political Constitutionalism in Contemporary China: Gao Quanxi’s Studies on China’s Political Constitution Chinese Albert H. Y. Chen The State-of-the-Field Review Special Issue Research on Chinese Investigative Journalism,