The Glorious Revolution Pdf, Epub, Ebook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brycheiniog Vol 42:44036 Brycheiniog 2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 1

68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 1 BRYCHEINIOG Cyfnodolyn Cymdeithas Brycheiniog The Journal of the Brecknock Society CYFROL/VOLUME XLII 2011 Golygydd/Editor BRYNACH PARRI Cyhoeddwyr/Publishers CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG A CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY AND MUSEUM FRIENDS 68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 2 CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG a CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY and MUSEUM FRIENDS SWYDDOGION/OFFICERS Llywydd/President Mr K. Jones Cadeirydd/Chairman Mr J. Gibbs Ysgrifennydd Anrhydeddus/Honorary Secretary Miss H. Gichard Aelodaeth/Membership Mrs S. Fawcett-Gandy Trysorydd/Treasurer Mr A. J. Bell Archwilydd/Auditor Mrs W. Camp Golygydd/Editor Mr Brynach Parri Golygydd Cynorthwyol/Assistant Editor Mr P. W. Jenkins Curadur Amgueddfa Brycheiniog/Curator of the Brecknock Museum Mr N. Blackamoor Pob Gohebiaeth: All Correspondence: Cymdeithas Brycheiniog, Brecknock Society, Amgueddfa Brycheiniog, Brecknock Museum, Rhodfa’r Capten, Captain’s Walk, Aberhonddu, Brecon, Powys LD3 7DS Powys LD3 7DS Ôl-rifynnau/Back numbers Mr Peter Jenkins Erthyglau a llyfrau am olygiaeth/Articles and books for review Mr Brynach Parri © Oni nodir fel arall, Cymdeithas Brycheiniog a Chyfeillion yr Amgueddfa piau hawlfraint yr erthyglau yn y rhifyn hwn © Except where otherwise noted, copyright of material published in this issue is vested in the Brecknock Society & Museum Friends 68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 3 CYNNWYS/CONTENTS Swyddogion/Officers -

Why Did Britain Become a Republic? > New Government

Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Why did Britain become a republic? Case study 2: New government Even today many people are not aware that Britain was ever a republic. After Charles I was put to death in 1649, a monarch no longer led the country. Instead people dreamed up ideas and made plans for a different form of government. Find out more from these documents about what happened next. Report on the An account of the Poem on the arrest of setting up of the new situation in Levellers, 1649 Commonwealth England, 1649 Portrait & symbols of Cromwell at the The setting up of Cromwell & the Battle of the Instrument Commonwealth Worcester, 1651 of Government http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Page 1 Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Case study 2: New government - Source 1 A report on the arrest of some Levellers, 29 March 1649 (Catalogue ref: SP 25/62, pp.134-5) What is this source? This is a report from a committee of MPs to Parliament. It explains their actions against the leaders of the Levellers. One of the men they arrested was John Lilburne, a key figure in the Leveller movement. What’s the background to this source? Before the war of the 1640s it was difficult and dangerous to come up with new ideas and try to publish them. However, during the Civil War censorship was not strongly enforced. Many political groups emerged with new ideas at this time. One of the most radical (extreme) groups was the Levellers. -

Cromwelliana 2012

CROMWELLIANA 2012 Series III No 1 Editor: Dr Maxine Forshaw CONTENTS Editor’s Note 2 Cromwell Day 2011: Oliver Cromwell – A Scottish Perspective 3 By Dr Laura A M Stewart Farmer Oliver? The Cultivation of Cromwell’s Image During 18 the Protectorate By Dr Patrick Little Oliver Cromwell and the Underground Opposition to Bishop 32 Wren of Ely By Dr Andrew Barclay From Civilian to Soldier: Recalling Cromwell in Cambridge, 44 1642 By Dr Sue L Sadler ‘Dear Robin’: The Correspondence of Oliver Cromwell and 61 Robert Hammond By Dr Miranda Malins Mrs S C Lomas: Cromwellian Editor 79 By Dr David L Smith Cromwellian Britain XXIV : Frome, Somerset 95 By Jane A Mills Book Reviews 104 By Dr Patrick Little and Prof Ivan Roots Bibliography of Books 110 By Dr Patrick Little Bibliography of Journals 111 By Prof Peter Gaunt ISBN 0-905729-24-2 EDITOR’S NOTE 2011 was the 360th anniversary of the Battle of Worcester and was marked by Laura Stewart’s address to the Association on Cromwell Day with her paper on ‘Oliver Cromwell: a Scottish Perspective’. ‘Risen from Obscurity – Cromwell’s Early Life’ was the subject of the study day in Huntingdon in October 2011 and three papers connected with the day are included here. Reflecting this subject, the cover illustration is the picture ‘Cromwell on his Farm’ by Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893), painted in 1874, and reproduced here courtesy of National Museums Liverpool. The painting can be found in the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight Village, Wirral, Cheshire. In this edition of Cromwelliana, it should be noted that the bibliography of journal articles covers the period spring 2009 to spring 2012, addressing gaps in the past couple of years. -

Chapter 4 English History Anglo Saxon: 450 – 1066 A.D. – Mixed With

Chapter 4 English History Anglo Saxon: 450 – 1066 A.D. – mixed with the natives of the island Native Brits + Germans = rule the Island of England 1066 A.D. – Norman Conquest: William of Normandy France conquers the Island of England (the Anglo Saxons) 1st Norman King – King William I Kings are technically Warlords - to become King you need to kill = own all the land Feudalism King = protection Kings Army (Dukes – Knights) = in charge of making money, make sure the serfs are doing their job Money = Scutage = Tax Serf = work the land Everyone under the King = King’s subjects 1189 – 1199 A.D. – King Richard (Lionheart) died in battle in France Lionheart was part of the 3rd Crusade 1199 – 1216 A.D. King John (Lackland) Tyrant King – abused his power Taxed his nobles relentlessly - 1215 A.D. Baronial Revolt – Nobles rebelled against the King and make him sign a document. They created the Magna Carta (Great Charter) – Gives rights to the Nobles. This lessens the kings power. At this time a middle class is being created, but HOW? This middle class becomes the downfall of feudalism. The middle class is called the Yeoman. (Human bowmen). Went and fought in the war, but got paid. They were smarter and had some money. 1216 – 1272 A.D. King Henry III He was 9 years old when he became King. 1258 – Henry’s cousin, a noble, Simon de Montforte, assembled many of the other Nobles, Knights, and Clergy to create what is now called the House of Lords. The House of Lords represents the nobles/wealthy people. -

History Term 4

History: Why were Kings back in Fashion by 1660? Year 7 Term 4 Timeline Key Terms Key Questions 1625 Charles I becomes King of England. Civil War A war between people of the same country. What Caused the English Civil War? The Divine Right of Kings — Charles I felt that God had given him Charles closes Parliament. The Eleven Years of This is a belief that the King or Queen is the most 1629 Divine Right of the power to rule and so Parliament should follow his leadership. Tyranny begin. powerful person on earth as God put them into Kings Parliament disagreed with the King over the Divine Right of Kings. power. Parliament believed it should have an important role in running the Charles reopens Parliament in order to raise 1640 country. money for war. Parliament tried to limit the King’s power. Charles responded by Eleven Years Charles I ruled England without Parliament for declaring war on Parliament in 1642. Tyranny eleven years. Charles I attempts to arrest 5 members of 1642 parliament. The English Civil War begins. Why did Parliament Win the War? A government where a King or Queen is the Head of Monarchy 1644 Parliamentarians win the Battle of Marston Moor. State. The New Model Army was created by Parliamentarians in 1645. These soldiers were paid for their services and trained well. 1645 Parliamentarians win the Battle of Naseby. A group in the UK elected by the people. They have Parliament had more money. They controlled the south of England Parliament which was much richer in resources. -

Abbreviations, 188 Accounts of the Society, 162-3 Aethelred II, Coins Of

INDEX Abbreviations, 188 COWELL, M.R. and E.M. BESLY, The metrology of the Accounts of the Society, 162-3 English Civil War coinages of Charles I, 57-75 Aethelred II, coins of, 124, 153 CUDDEFORD, M.J., Contributions to the Coin Register, 143, Alnage seals, 31-6 145, 149-50, 155 Aquitaine, coins of, 151-2, 155 Cunobelin, coins of, 144-6 ARCHIBALD, MARION M., Contributions to the Coin Regis- ter, 150-2, 154 DAVIES, J.A., Contributions to the Coin Register, 151-5 — Dating Stephen's first type, 9-22 DICKINSON, M., Contributions to paper by Greenall, 94-120 ATTWOOD, P., Robert Johnson and a railway centenary Dublin mint of Edward I, 23-30 medal, 139-40 DUNGER, G.T., Contributions to the Coin Register, 152,155 Austria, coins of, 88, 136 Eadwald of E. Anglia, coin of, 152 Edinburgh, mint, 126-9 Baldred, coin of, 153 Edward the Elder, coin of, 153 Bar, coin of, 155 Edward the Martyr, coin of, 153 BARBER, P., Review of Woolf's The medallic record of the Edward VI, coins of, 79, 86 Jacobite movement, 156-7 EGAN, G., Alnage seals and the national coinage - some BARCLAY, C.P., A Civil War hoard from Grewelthorpe, parallels in design, 31-6 North Yorkshire, 76-81 Elizabeth I, coins of, 79, 86, 134 — Review of Attwood's British Museum Occasional Paper Eppillus, coins of, 146 76, Acquisitions of Badges (1983-1987), 158 BATESON, J.D., The 1991 Kelso Treasure Trove, 82-9 EEARON, D., Review of Attwood's British Museum Occa- — A late seventeenth century hoard from Fauldhouse, West sional Paper 78, Acquisitions of Medals (1983-1987), Lothian, 133-6 157-8 Bellovaci, coin of, 143 Finds (for single finds, see the geographical index to the Beonna of E. -

In England, Scotland, and Wales: Texts, Purpose, Context, 1138-1530

Victoria Shirley The Galfridian Tradition(s) in England, Scotland, and Wales: Texts, Purpose, Context, 1138-1530 A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature Cardiff University 2017 i Abstract This thesis examines the responses to and rewritings of the Historia regum Britanniae in England, Scotland, and Wales between 1138 and 1530, and argues that the continued production of the text was directly related to the erasure of its author, Geoffrey of Monmouth. In contrast to earlier studies, which focus on single national or linguistic traditions, this thesis analyses different translations and adaptations of the Historia in a comparative methodology that demonstrates the connections, contrasts and continuities between the various national traditions. Chapter One assesses Geoffrey’s reputation and the critical reception of the Historia between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries, arguing that the text came to be regarded as an authoritative account of British history at the same time as its author’s credibility was challenged. Chapter Two analyses how Geoffrey’s genealogical model of British history came to be rewritten as it was resituated within different narratives of English, Scottish, and Welsh history. Chapter Three demonstrates how the Historia’s description of the island Britain was adapted by later writers to construct geographical landscapes that emphasised the disunity of the island and subverted Geoffrey’s vision of insular unity. Chapter Four identifies how the letters between Britain and Rome in the Historia use argumentative rhetoric, myths of descent, and the discourse of freedom to establish the importance of political, national, or geographical independence. Chapter Five analyses how the relationships between the Arthur and his immediate kin group were used to challenge Geoffrey’s narrative of British history and emphasise problems of legitimacy, inheritance, and succession. -

Introduction to British History I

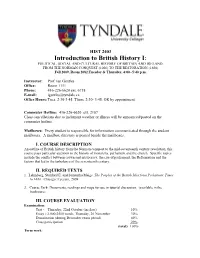

HIST 2403 Introduction to British History I: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND, FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST (1066) TO THE RESTORATION (1660) Fall 2009, Room 2082,Tuesday & Thursday, 4:00--5:40 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Ian Gentles Office: Room 1111 Phone: 416-226-6620 ext. 6718 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:30-3:45, Thurs. 2:30- 3:45, OR by appointment Commuter Hotline: 416-226-6620 ext. 2187 Class cancellations due to inclement weather or illness will be announced/posted on the commuter hotline. Mailboxes: Every student is responsible for information communicated through the student mailboxes. A mailbox directory is posted beside the mailboxes. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION An outline of British history from the Norman conquest to the mid-seventeenth century revolution, this course pays particular attention to the history of monarchy, parliament and the church. Specific topics include the conflict between crown and aristocracy, the rise of parliament, the Reformation and the factors that led to the turbulence of the seventeenth century. II. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Lehmberg, Stanford E. and Samantha Meigs. The Peoples of the British Isles from Prehistoric Times to 1688 . Chicago: Lyceum, 2009 2. Course Pack: Documents, readings and maps for use in tutorial discussion. (available in the bookstore) III. COURSE EVALUATION Examination : Test - Thursday, 22nd October (in class) 10% Essay - 2,000-2500 words, Thursday, 26 November 30% Examination (during December exam period) 40% Class participation 20% (total) 100% Term work : a. You are expected to attend the tutorials, preparing for them through the lectures and through assigned reading. -

Of BNJ Contents 1903-2016

CONTENTS OF THE BRITISH NUMISMATIC JOURNAL VOLUMES 1 TO 86 (1903/4 - 2016) Edited for the British Numismatic Society by R. H. Thompson, FSA, MCLIP. 2011-16 Additions by R. Page, MSc, DIC. 2019 © THE BRITISH NUMISMATIC SOCIETY 2011 INTRODUCTION This listing is confined to the principal contributions to the Journal, including short articles and notes, but omitting reviews, exhibitions, and other proceedings of the Society; presidential addresses, however, have been included to the extent that they treat specific subjects. This list does not pretend to be an index; and users may like to note that there are (in addition to the indexes in each volume) cumulated indexes to each series as follows: Volumes 1-10 In vol. 10, pp. 393-402 11-20 20, pp. 397-410 21-30 30, pp. 396-417 31-40 40, pp. 209-239 41-50 50, pp. 161-185 51-60 60, pp.191-209 61-70 70, pp. 203-213. 71-80 81, pp. 319-333 In the references the volume number is given in arabic numerals, the roman numerals of the first fifty volumes being converted into arabic. The year is the titular date of the volume, not the date of publication, nor (where they differ) the years of the proceedings contained in that volume. The numbers of plates given in the references are the pages of illustrations (including charts, facsimiles, and maps) which are additional to the text pages; in Volumes 52-57, and occasionally elsewhere, the plates are incorporated in the numbering of pages. The aim of the subject arrangement is to display the contents under convenient headings, subdivided where references are numerous; and most papers appear in one place only. -

The Ideology of Jury Law-Finding in the Interregnum

Conscience and the True Law: 5 The Ideology of Jury Law-Finding in the Interregnum The government that tried and condemned Charles I in January, 1649, found later the same year that it was unable to have its way with John Lilburne. As leader of the Levellers, the most imposing of the groups that clashed with the Cromwellian regime, Lilburne appealed to his jurors, in a celebrated phrase, "as judges of law as well as fact. " 1 When the jury acquitted him of treason, this claim to a "jury right"-a right of the jury to decide the law-brought the criminal trial jury for the first time into the forefront of English constitutional and political debate.2 The emergence of a theory of the jury's right to decide the law was not in any simple way a reaction to the transformation of criminal process in early modern England. On the one hand, much of what the radical reformers attacked predated the Tudor period; on the other, much of their program was inspired by the political crisis that accompanied the struggle against the Stuart monarchy .3 Nevertheless, the Leveller attack on the judiciary in criminal cases was a response to the power and behavior of the bench, and that power and behavior were largely owing to new forms of criminal procedure. 1. See below, text at nn. 67-77. On the Levellers see e.g. H. N. Brailsford, The Levellers and the English Revolution (London, 1961); Joseph Frank, The Levellers (Cambridge, Mass., 1955); G. E. Aylmer, ed., The Levellers in the English Revolution (London, 1975), pp. -

Key to London Map of Days

A London Map of Days This is the key to the daily details that feature on my etching A London Map of Days. I posted these every day on both Facebook and Twitter from the 9 February 2015 through to 8 February 2016. As the project continued, I began to enjoy myself and treat it more like a blog and so there is a marked difference between the amount of detail I have included at the beginning and the end of that year. 1 January 1660 Samuel Pepys begins writing his famous diary. He started the diary when he was only 26 years old and kept it for 10 years. He was a naval administrator and even though he had no maritime experience, he rose by a combination of hard work, patronage and talent for administration to be the Chief Secretary to the Admiralty under King Charles II and King James II. His diary, which was not published until the 19th century was written in a cryptic, personal shorthand and the first person to fully transcribe it, did so without the benefit of the key. It was not until 1970 that an unabridged version was published as previous editions had omitted passages deemed too obscene to print, usually involving Pepys sexual exploits. The diary combines personal anecdotes (often centred around drinking) with eyewitness accounts of great events such as the Great Plague of London, the Second Dutch War and the Great Fire of London. It is a glorious work and was a constant source of inspiration for my map. Daily detail from A London Map of Days. -

Radical Republicanism in England, America, and the Imperial Atlantic, 1624-1661

RADICAL REPUBLICANISM IN ENGLAND, AMERICA, AND THE IMPERIAL ATLANTIC, 1624-1661 by John Donoghue B.A., Westminster College, New Wilmington, PA, 1993 M.A., University of Pittsburgh, 1999 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2006 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Faculty of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by John Donoghue It was defended on December 2, 2005 and approved by William Fusfield, Associate Professor, Department of Communication Janelle Greenberg, Professor, Department of History Jonathan Scott, Professor, Department of History Dissertation Director: Marcus Rediker, Professor, Department of History ii Copyright by John Donoghue 2006 iii RADICAL REPUBLICANISM IN ENGLAND, AMERICA, AND THE IMPERIAL ATLANTIC, 1624-1661 John Donoghue, Ph.D. University of Pittsburgh, April 30, 2006 This dissertation links the radical politics of the English Revolution to the history of puritan New England. It argues that antinomians, by rejecting traditional concepts of social authority, created divisive political factions within the godly party while it waged war against King Charles I. At the same time in New England, antinomians organized a political movement that called for a democratic commonwealth to limit the power of ministers and magistrates in religious and civil affairs. When this program collapsed in Massachusetts, hundreds of colonists returned to an Old England engulfed by civil war. Joining English antinomians, they became lay preachers in London, New Model Army soldiers, and influential supporters of the republican Levellers. This dissertation also connects the study of republican political thought to the labor history of the first British Empire.