Usurper Or Peacekeeper? Redefining Oliver Cromwell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brycheiniog Vol 42:44036 Brycheiniog 2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 1

68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 1 BRYCHEINIOG Cyfnodolyn Cymdeithas Brycheiniog The Journal of the Brecknock Society CYFROL/VOLUME XLII 2011 Golygydd/Editor BRYNACH PARRI Cyhoeddwyr/Publishers CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG A CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY AND MUSEUM FRIENDS 68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 2 CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG a CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY and MUSEUM FRIENDS SWYDDOGION/OFFICERS Llywydd/President Mr K. Jones Cadeirydd/Chairman Mr J. Gibbs Ysgrifennydd Anrhydeddus/Honorary Secretary Miss H. Gichard Aelodaeth/Membership Mrs S. Fawcett-Gandy Trysorydd/Treasurer Mr A. J. Bell Archwilydd/Auditor Mrs W. Camp Golygydd/Editor Mr Brynach Parri Golygydd Cynorthwyol/Assistant Editor Mr P. W. Jenkins Curadur Amgueddfa Brycheiniog/Curator of the Brecknock Museum Mr N. Blackamoor Pob Gohebiaeth: All Correspondence: Cymdeithas Brycheiniog, Brecknock Society, Amgueddfa Brycheiniog, Brecknock Museum, Rhodfa’r Capten, Captain’s Walk, Aberhonddu, Brecon, Powys LD3 7DS Powys LD3 7DS Ôl-rifynnau/Back numbers Mr Peter Jenkins Erthyglau a llyfrau am olygiaeth/Articles and books for review Mr Brynach Parri © Oni nodir fel arall, Cymdeithas Brycheiniog a Chyfeillion yr Amgueddfa piau hawlfraint yr erthyglau yn y rhifyn hwn © Except where otherwise noted, copyright of material published in this issue is vested in the Brecknock Society & Museum Friends 68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 3 CYNNWYS/CONTENTS Swyddogion/Officers -

War of Roses: a House Divided

Stanford Model United Nations Conference 2014 War of Roses: A House Divided Chairs: Teo Lamiot, Gabrielle Rhoades Assistant Chair: Alyssa Liew Crisis Director: Sofia Filippa Table of Contents Letters from the Chairs………………………………………………………………… 2 Letter from the Crisis Director………………………………………………………… 4 Introduction to the Committee…………………………………………………………. 5 History and Context……………………………………………………………………. 5 Characters……………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Topics on General Conference Agenda…………………………………..……………. 9 Family Tree ………………………………………………………………..……………. 12 Special Committee Rules……………………………………………………………….. 13 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………. 14 Letters from the Chairs Dear Delegates, My name is Gabrielle Rhoades, and it is my distinct pleasure to welcome you to the Stanford Model United Nations Conference (SMUNC) 2014 as members of the The Wars of the Roses: A House Divided Joint Crisis Committee! As your Wars of the Roses chairs, Teo Lamiot and I have been working hard with our crisis director, Sofia Filippa, and SMUNC Secretariat members to make this conference the best yet. If you have attended SMUNC before, I promise that this year will be even more full of surprise and intrigue than your last conference; if you are a newcomer, let me warn you of how intensely fun and challenging this conference will assuredly be. Regardless of how you arrive, you will all leave better delegates and hopefully with a reinvigorated love for Model UN. My own love for Model United Nations began when I co-chaired a committee for SMUNC (The Arab Spring), which was one of my very first experiences as a member of the Society for International Affairs at Stanford (the umbrella organization for the MUN team), and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Later that year, I joined the intercollegiate Model United Nations team. -

Being a Thesis Submitted for the Degree Of

The tJni'ers1ty of Sheffield Depaz'tient of Uistory YORKSRIRB POLITICS, 1658 - 1688 being a ThesIs submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by CIthJUL IARGARRT KKI August, 1990 For my parents N One of my greater refreshments is to reflect our friendship. "* * Sir Henry Goodricke to Sir Sohn Reresby, n.d., Kxbr. 1/99. COff TENTS Ackn owl edgements I Summary ii Abbreviations iii p Introduction 1 Chapter One : Richard Cromwell, Breakdown and the 21 Restoration of Monarchy: September 1658 - May 1660 Chapter Two : Towards Settlement: 1660 - 1667 63 Chapter Three Loyalty and Opposition: 1668 - 1678 119 Chapter Four : Crisis and Re-adjustment: 1679 - 1685 191 Chapter Five : James II and Breakdown: 1685 - 1688 301 Conclusion 382 Appendix: Yorkshire )fembers of the Coir,ons 393 1679-1681 lotes 396 Bibliography 469 -i- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Research for this thesis was supported by a grant from the Department of Education and Science. I am grateful to the University of Sheffield, particularly the History Department, for the use of their facilities during my time as a post-graduate student there. Professor Anthony Fletcher has been constantly encouraging and supportive, as well as a great friend, since I began the research under his supervision. I am indebted to him for continuing to supervise my work even after he left Sheffield to take a Chair at Durham University. Following Anthony's departure from Sheffield, Professor Patrick Collinson and Dr Mark Greengrass kindly became my surrogate supervisors. Members of Sheffield History Department's Early Modern Seminar Group were a source of encouragement in the early days of my research. -

HISTORY MEDIUM TERM PLAN (MTP) YEAR 4 2020: Taught 1St Half of Each Term HISTORY MTP Y4 Autumn 1: 8 WEEKS Spring 1: 6 WEEKS Su

HISTORY MEDIUM TERM PLAN (MTP) YEAR 4 2020: Taught 1st half of each term HISTORY Autumn 1: 8 WEEKS Spring 1: 6 WEEKS Summer 1: 6 WEEKS MTP Y4 Topic Title: Anglo-Saxons / Scots Topic Title: Vikings Topic Title: UK Parliament Taken from the Year Key knowledge: Key knowledge: Key knowledge: group • Roman withdrawal from Britain in CE • Viking raids and the resistance of Alfred the Great and • Establishment of the parliament - division of the curriculum 410 and the fall of the western Roman Athelstan. Houses of Lords and Commons. map Empire. • Edward the Confessor and his death in 1066 - prelude to • Scots invasions from Ireland to north the Battle of Hastings. Key Skills: Britain (now Scotland). • Anglo-Saxons invasions, settlements and Key Skills: kingdoms; place names and village life • Choose reliable sources of information to find out culture and Christianity (eg. Canterbury, about the past. Iona, and Lindisfarne) • Choose reliable sources of information to find out about • Give own reasons why changes may have occurred, the past. backed up by evidence. • Give own reasons why changes may have occurred, • Describe similarities and differences between people, Key Skills: backed up by evidence. events and artefacts. • Describe similarities and differences between people, • Describe how historical events affect/influence life • Choose reliable sources of information events and artefacts. today. to find out about the past. • Describe how historical events affect/influence life today. Chronological understanding • Give own reasons why changes may Chronological understanding • Understand that a timeline can be divided into BCE have occurred, backed up by evidence. • Understand that a timeline can be divided into BCE and and CE. -

Paper 2: Power: Monarchy and Democracy in Britain C1000-2014

Paper 2: Power: Monarchy and democracy in Britain c1000-2014. 1. Describe the Anglo-Saxon system of government. [4] • Witan –The relatives of the King, the important nobles (Earls) and churchmen (Bishops) made up the Kings council which was known as the WITAN. These men led the armies and ruled the shires on behalf of the king. In return, they received wealth, status and land. • At local level the lesser nobles (THEGNS) carried out the roles of bailiffs and estate management. Each shire was divided into HUNDREDS. These districts had their own law courts and army. • The Church handled many administrative roles for the King because many churchmen could read and write. The Church taught the ordinary people about why they should support the king and influence his reputation. They also wrote down the history of the period. 2. Explain why the Church was important in Anglo-Saxon England. [8] • The church was flourishing in Aethelred’s time (c.1000). Kings and noblemen gave the church gifts of land and money. The great MINSTERS were in Rochester, York, London, Canterbury and Winchester. These Churches were built with donations by the King. • Nobles provided money for churches to be built on their land as a great show of status and power. This reminded the local population of who was in charge. It hosted community events as well as religious services, and new laws or taxes would be announced there. Building a church was the first step in building a community in the area. • As churchmen were literate some of the great works of learning, art and culture. -

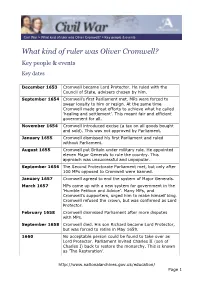

What Kind of Ruler Was Oliver Cromwell? > Key People & Events

Civil War > What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? > Key people & events What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? Key people & events Key dates December 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector. He ruled with the Council of State, advisers chosen by him. September 1654 Cromwell’s first Parliament met. MPs were forced to swear loyalty to him or resign. At the same time Cromwell made great efforts to achieve what he called ‘healing and settlement’. This meant fair and efficient government for all. November 1654 Cromwell introduced excise (a tax on all goods bought and sold). This was not approved by Parliament. January 1655 Cromwell dismissed his first Parliament and ruled without Parliament. August 1655 Cromwell put Britain under military rule. He appointed eleven Major Generals to rule the country. This approach was unsuccessful and unpopular. September 1656 The Second Protectorate Parliament met, but only after 100 MPs opposed to Cromwell were banned. January 1657 Cromwell agreed to end the system of Major Generals. March 1657 MPs came up with a new system for government in the ‘Humble Petition and Advice’. Many MPs, and Cromwell’s supporters, urged him to make himself king. Cromwell refused the crown, but was confirmed as Lord Protector. February 1658 Cromwell dismissed Parliament after more disputes with MPs. September 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was forced to retire in May 1659. 1660 No acceptable person could be found to take over as Lord Protector. Parliament invited Charles II (son of Charles I) back to restore the monarchy. This is known as ‘The Restoration’. -

Why Did Britain Become a Republic? > New Government

Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Why did Britain become a republic? Case study 2: New government Even today many people are not aware that Britain was ever a republic. After Charles I was put to death in 1649, a monarch no longer led the country. Instead people dreamed up ideas and made plans for a different form of government. Find out more from these documents about what happened next. Report on the An account of the Poem on the arrest of setting up of the new situation in Levellers, 1649 Commonwealth England, 1649 Portrait & symbols of Cromwell at the The setting up of Cromwell & the Battle of the Instrument Commonwealth Worcester, 1651 of Government http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Page 1 Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Case study 2: New government - Source 1 A report on the arrest of some Levellers, 29 March 1649 (Catalogue ref: SP 25/62, pp.134-5) What is this source? This is a report from a committee of MPs to Parliament. It explains their actions against the leaders of the Levellers. One of the men they arrested was John Lilburne, a key figure in the Leveller movement. What’s the background to this source? Before the war of the 1640s it was difficult and dangerous to come up with new ideas and try to publish them. However, during the Civil War censorship was not strongly enforced. Many political groups emerged with new ideas at this time. One of the most radical (extreme) groups was the Levellers. -

Cromwelliana 2012

CROMWELLIANA 2012 Series III No 1 Editor: Dr Maxine Forshaw CONTENTS Editor’s Note 2 Cromwell Day 2011: Oliver Cromwell – A Scottish Perspective 3 By Dr Laura A M Stewart Farmer Oliver? The Cultivation of Cromwell’s Image During 18 the Protectorate By Dr Patrick Little Oliver Cromwell and the Underground Opposition to Bishop 32 Wren of Ely By Dr Andrew Barclay From Civilian to Soldier: Recalling Cromwell in Cambridge, 44 1642 By Dr Sue L Sadler ‘Dear Robin’: The Correspondence of Oliver Cromwell and 61 Robert Hammond By Dr Miranda Malins Mrs S C Lomas: Cromwellian Editor 79 By Dr David L Smith Cromwellian Britain XXIV : Frome, Somerset 95 By Jane A Mills Book Reviews 104 By Dr Patrick Little and Prof Ivan Roots Bibliography of Books 110 By Dr Patrick Little Bibliography of Journals 111 By Prof Peter Gaunt ISBN 0-905729-24-2 EDITOR’S NOTE 2011 was the 360th anniversary of the Battle of Worcester and was marked by Laura Stewart’s address to the Association on Cromwell Day with her paper on ‘Oliver Cromwell: a Scottish Perspective’. ‘Risen from Obscurity – Cromwell’s Early Life’ was the subject of the study day in Huntingdon in October 2011 and three papers connected with the day are included here. Reflecting this subject, the cover illustration is the picture ‘Cromwell on his Farm’ by Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893), painted in 1874, and reproduced here courtesy of National Museums Liverpool. The painting can be found in the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight Village, Wirral, Cheshire. In this edition of Cromwelliana, it should be noted that the bibliography of journal articles covers the period spring 2009 to spring 2012, addressing gaps in the past couple of years. -

Rump Ballads and Official Propaganda (1660-1663)

Ezra’s Archives | 35 A Rhetorical Convergence: Rump Ballads and Official Propaganda (1660-1663) Benjamin Cohen In October 1917, following the defeat of King Charles I in the English Civil War (1642-1649) and his execution, a series of republican regimes ruled England. In 1653 Oliver Cromwell’s Protectorate regime overthrew the Rump Parliament and governed England until his death in 1659. Cromwell’s regime proved fairly stable during its six year existence despite his ruling largely through the powerful New Model Army. However, the Protectorate’s rapid collapse after Cromwell’s death revealed its limited durability. England experienced a period of prolonged political instability between the collapse of the Protectorate and the restoration of monarchy. Fears of political and social anarchy ultimately brought about the restoration of monarchy under Charles I’s son and heir, Charles II in May 1660. The turmoil began when the Rump Parliament (previously ascendant in 1649-1653) seized power from Oliver Cromwell’s ineffectual son and successor, Richard, in spring 1659. England’s politically powerful army toppled the regime in October, before the Rump returned to power in December 1659. Ultimately, the Rump was once again deposed at the hands of General George Monck in February 1660, beginning a chain of events leading to the Restoration.1 In the following months Monck pragmatically maneuvered England toward a restoration and a political 1 The Rump Parliament refers to the Parliament whose membership was composed of those Parliamentarians that remained following the expulsion of members unwilling to vote in favor of executing Charles I and establishing a commonwealth (republic) in 1649. -

Pennsylvania Magazine of HISTORY and BIOGRAPHY

THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY Governor John Blackwell: His Life in England and Ireland OHN BLACKWELL is best known to American readers as an early governor of Pennsylvania, the most recent account of his J governorship having been published in this Magazine in 1950. Little, however, has been written about his services to the Common- wealth government, first as one of Oliver Cromwell's trusted cavalry officers and, subsequently, as his Treasurer at War, a position of considerable importance and responsibility.1 John Blackwell was born in 1624,2 the eldest son of John Black- well, Sr., who exercised considerable influence on his son's upbringing and activities. John Blackwell, Sr., Grocer to King Charles I, was a wealthy London merchant who lived in the City and had a country house at Mortlake, on the outskirts of London.3 In 1640, when the 1 Nicholas B. Wainwright, "Governor John Blackwell," The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (PMHB), LXXIV (1950), 457-472.I am indebted to Professor Wallace Notestein for advice and suggestions. 2 John Blackwell, Jr., was born Mar. 8, 1624. Miscellanea Heraldica et Genealogica, New Series, I (London, 1874), 177. 3 John Blackwell, Sr., was born at Watford, Herts., Aug. 25, 1594. He married his first wife Juliana (Gillian) in 1621; she died in 1640, and was buried at St. Thomas the Apostle, London, having borne him ten children. On Mar. 9, 1642, he married Martha Smithsby, by whom he had eight children. Ibid.y 177-178. For Blackwell arms, see J. Foster, ed., Grantees 121 122, W. -

S. N. S. College, Jehanabad

S. N. S. COLLEGE, JEHANABAD (A Constituent unit of Magadh University, Bodh Gaya) DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY KEY-NOTES JAMES-I (1603-1625) FOR B.A. PART – I BY KRITI SINGH ANAND, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR, DEPTT. OF HISTORY, S.N. SINHA COLLEGE, JEHANABAD 1 James I (1603 - 1625) James VI King of Scotland was the great grandson of Margaret, the daughter of HenryVIII of England. The accession of James Stuart to the English throne as James I, on the death of Elizabeth in 1603, brought about the peaceful union of the rival monarchies of England and Scotland. He tried to make the union of two very different lands complete by assuming the title of King of Great Britain. There was peace in England and people did not fear any danger from a disputed succession inside the country or from external aggression. So strong monarchy was not considered essential for the welfare of the people. Even towards the end of the reign of Queen Elizabeth, Parliament began to oppose the royal will. The attempts of the new king to make the two lands to have one parliament, one church and one law failed miserably, because the Scots were not interested in the union and the English Parliament did not co- operate with him for it did not trust him. James I had experience as the King of Scotland and he knew very well the history of the absolute rule of the Tudor monarchs in England. So he was determined to rule with absolute powers. He believed in the theory of Divine Right Kingship and his own accession to the English throne was sanctioned by this theory. -

'A Chief Standard Work': the Rise and Fall of David Hume's' History of England'. 1754-C. 1900

’A CHIEF STANDARD WORK’: THE RISE AND FALL OF DAVID HUME’S HISTORY OF ENGLAND. 1754-C.1900. UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PhD THESIS JAMES ANDREW GEORGE BAVERSTOCK UNIVERSITY COLLEGE [LONOIK. ProQuest Number: 10018558 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10018558 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract. This thesis examines the influence of David Hume’s History of England during the century of its greatest popularity. It explores how far the long-term fortunes of Hume’s text matched his original aims for the work. Hume’s success in creating a classic popular narrative is demonstrated, but is contrasted with the History's failure to promote the polite ’coalition of parties’ he wished for. Whilst showing that Hume’s popularity contributed to tempering some of the teleological excesses of the ’whig version’ of English history, it is stressed that his work signally failed in dampening ’Whig’/ ’Tory’ conflict. Rather than provide a new frame of reference for British politics, as Hume had intended, the History was absorbed into national political culture as a ’Tory’ text - with important consequences for Hume’s general reputation as a thinker.