Paper 2: Power: Monarchy and Democracy in Britain C1000-2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War of Roses: a House Divided

Stanford Model United Nations Conference 2014 War of Roses: A House Divided Chairs: Teo Lamiot, Gabrielle Rhoades Assistant Chair: Alyssa Liew Crisis Director: Sofia Filippa Table of Contents Letters from the Chairs………………………………………………………………… 2 Letter from the Crisis Director………………………………………………………… 4 Introduction to the Committee…………………………………………………………. 5 History and Context……………………………………………………………………. 5 Characters……………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Topics on General Conference Agenda…………………………………..……………. 9 Family Tree ………………………………………………………………..……………. 12 Special Committee Rules……………………………………………………………….. 13 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………. 14 Letters from the Chairs Dear Delegates, My name is Gabrielle Rhoades, and it is my distinct pleasure to welcome you to the Stanford Model United Nations Conference (SMUNC) 2014 as members of the The Wars of the Roses: A House Divided Joint Crisis Committee! As your Wars of the Roses chairs, Teo Lamiot and I have been working hard with our crisis director, Sofia Filippa, and SMUNC Secretariat members to make this conference the best yet. If you have attended SMUNC before, I promise that this year will be even more full of surprise and intrigue than your last conference; if you are a newcomer, let me warn you of how intensely fun and challenging this conference will assuredly be. Regardless of how you arrive, you will all leave better delegates and hopefully with a reinvigorated love for Model UN. My own love for Model United Nations began when I co-chaired a committee for SMUNC (The Arab Spring), which was one of my very first experiences as a member of the Society for International Affairs at Stanford (the umbrella organization for the MUN team), and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Later that year, I joined the intercollegiate Model United Nations team. -

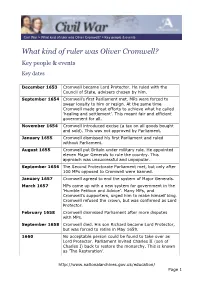

What Kind of Ruler Was Oliver Cromwell? > Key People & Events

Civil War > What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? > Key people & events What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? Key people & events Key dates December 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector. He ruled with the Council of State, advisers chosen by him. September 1654 Cromwell’s first Parliament met. MPs were forced to swear loyalty to him or resign. At the same time Cromwell made great efforts to achieve what he called ‘healing and settlement’. This meant fair and efficient government for all. November 1654 Cromwell introduced excise (a tax on all goods bought and sold). This was not approved by Parliament. January 1655 Cromwell dismissed his first Parliament and ruled without Parliament. August 1655 Cromwell put Britain under military rule. He appointed eleven Major Generals to rule the country. This approach was unsuccessful and unpopular. September 1656 The Second Protectorate Parliament met, but only after 100 MPs opposed to Cromwell were banned. January 1657 Cromwell agreed to end the system of Major Generals. March 1657 MPs came up with a new system for government in the ‘Humble Petition and Advice’. Many MPs, and Cromwell’s supporters, urged him to make himself king. Cromwell refused the crown, but was confirmed as Lord Protector. February 1658 Cromwell dismissed Parliament after more disputes with MPs. September 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was forced to retire in May 1659. 1660 No acceptable person could be found to take over as Lord Protector. Parliament invited Charles II (son of Charles I) back to restore the monarchy. This is known as ‘The Restoration’. -

Why Did Britain Become a Republic? > New Government

Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Why did Britain become a republic? Case study 2: New government Even today many people are not aware that Britain was ever a republic. After Charles I was put to death in 1649, a monarch no longer led the country. Instead people dreamed up ideas and made plans for a different form of government. Find out more from these documents about what happened next. Report on the An account of the Poem on the arrest of setting up of the new situation in Levellers, 1649 Commonwealth England, 1649 Portrait & symbols of Cromwell at the The setting up of Cromwell & the Battle of the Instrument Commonwealth Worcester, 1651 of Government http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Page 1 Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Case study 2: New government - Source 1 A report on the arrest of some Levellers, 29 March 1649 (Catalogue ref: SP 25/62, pp.134-5) What is this source? This is a report from a committee of MPs to Parliament. It explains their actions against the leaders of the Levellers. One of the men they arrested was John Lilburne, a key figure in the Leveller movement. What’s the background to this source? Before the war of the 1640s it was difficult and dangerous to come up with new ideas and try to publish them. However, during the Civil War censorship was not strongly enforced. Many political groups emerged with new ideas at this time. One of the most radical (extreme) groups was the Levellers. -

Cromwelliana 2012

CROMWELLIANA 2012 Series III No 1 Editor: Dr Maxine Forshaw CONTENTS Editor’s Note 2 Cromwell Day 2011: Oliver Cromwell – A Scottish Perspective 3 By Dr Laura A M Stewart Farmer Oliver? The Cultivation of Cromwell’s Image During 18 the Protectorate By Dr Patrick Little Oliver Cromwell and the Underground Opposition to Bishop 32 Wren of Ely By Dr Andrew Barclay From Civilian to Soldier: Recalling Cromwell in Cambridge, 44 1642 By Dr Sue L Sadler ‘Dear Robin’: The Correspondence of Oliver Cromwell and 61 Robert Hammond By Dr Miranda Malins Mrs S C Lomas: Cromwellian Editor 79 By Dr David L Smith Cromwellian Britain XXIV : Frome, Somerset 95 By Jane A Mills Book Reviews 104 By Dr Patrick Little and Prof Ivan Roots Bibliography of Books 110 By Dr Patrick Little Bibliography of Journals 111 By Prof Peter Gaunt ISBN 0-905729-24-2 EDITOR’S NOTE 2011 was the 360th anniversary of the Battle of Worcester and was marked by Laura Stewart’s address to the Association on Cromwell Day with her paper on ‘Oliver Cromwell: a Scottish Perspective’. ‘Risen from Obscurity – Cromwell’s Early Life’ was the subject of the study day in Huntingdon in October 2011 and three papers connected with the day are included here. Reflecting this subject, the cover illustration is the picture ‘Cromwell on his Farm’ by Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893), painted in 1874, and reproduced here courtesy of National Museums Liverpool. The painting can be found in the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight Village, Wirral, Cheshire. In this edition of Cromwelliana, it should be noted that the bibliography of journal articles covers the period spring 2009 to spring 2012, addressing gaps in the past couple of years. -

Remembering King Charles I: History, Art and Polemics from the Restoration to the Reform Act T

REMEMBERING KING CHARLES I: HISTORY, ART AND POLEMICS FROM THE RESTORATION TO THE REFORM ACT T. J. Allen Abstract: The term Restoration can be used simply to refer to the restored monarchy under Charles II, following the Commonwealth period. But it can also be applied to a broader programme of restoring the crown’s traditional prerogatives and rehabilitating the reign of the king’s father, Charles I. Examples of this can be seen in the placement of an equestrian statue of Charles I at Charing Cross and a related poem by Edmund Waller. But these works form elements in a process that continued for 200 years in which the memory of Charles I fused with contemporary constitutional debates. The equestrian statue of Charles I at Charing Cross, produced by the French sculptor Hubert Le Sueur c1633 and erected in 1675. Photograph: T. J. Allen At the southern end of Trafalgar Square, looking towards Whitehall, stands an equestrian statue of Charles I. This is set on a pedestal whose design has been attributed to Sir Christopher Wren and was carved by Joshua Marshall, Master Mason to Charles II. The bronze figure was originally commissioned by Richard Weston (First Earl of Portland, the king’s Lord High Treasurer) and was produced by the French sculptor Hubert Le Sueur in the early 1630s. It originally stood in 46 VIDES 2014 the grounds of Weston’s house in Surrey, but as a consequence of the Civil War was later confiscated and then hidden. The statue’s existence again came to official attention following the Restoration, when it was acquired by the crown, and in 1675 placed in its current location. -

S. N. S. College, Jehanabad

S. N. S. COLLEGE, JEHANABAD (A Constituent unit of Magadh University, Bodh Gaya) DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY KEY-NOTES JAMES-I (1603-1625) FOR B.A. PART – I BY KRITI SINGH ANAND, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR, DEPTT. OF HISTORY, S.N. SINHA COLLEGE, JEHANABAD 1 James I (1603 - 1625) James VI King of Scotland was the great grandson of Margaret, the daughter of HenryVIII of England. The accession of James Stuart to the English throne as James I, on the death of Elizabeth in 1603, brought about the peaceful union of the rival monarchies of England and Scotland. He tried to make the union of two very different lands complete by assuming the title of King of Great Britain. There was peace in England and people did not fear any danger from a disputed succession inside the country or from external aggression. So strong monarchy was not considered essential for the welfare of the people. Even towards the end of the reign of Queen Elizabeth, Parliament began to oppose the royal will. The attempts of the new king to make the two lands to have one parliament, one church and one law failed miserably, because the Scots were not interested in the union and the English Parliament did not co- operate with him for it did not trust him. James I had experience as the King of Scotland and he knew very well the history of the absolute rule of the Tudor monarchs in England. So he was determined to rule with absolute powers. He believed in the theory of Divine Right Kingship and his own accession to the English throne was sanctioned by this theory. -

OLIVER CROMWELL: CHANGE and CONTINUITY a Master's Thesis Presented to the School of Graduate Studies Department Ofhistory Indian

OLIVER CROMWELL: CHANGE AND CONTINUITY A Master's Thesis Presented to The School of Graduate Studies Department ofHistory Indiana State University Terre Haute, Indiana In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree by Kari L. Ellis May2002 INDIANA STATE UM!VERSITY UBRARY ll APPROVAL SHEET The thesis ofKari L. Ellis, Contribution to the School of Graduate Studies, Indiana State University, Series I, Number 2166, under the title Oliver Cromwell: Change and Continuity is approved as partial fulfillment of the Master of Arts Degree in the amount of six semester hours of graduate credit. Committee Chairperson r 111 ABSTRACT This study looks at the life of Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector ofEngland, in an effort to clarify the diverse and conflicting interpretations resulting from a lack of agreement between those who are biased for and against the Lord Protector. The purpose of the study of this conflicting information is not to settle whether Cromwell was a good figure or bad, but to define more clearly his time. Cromwell, clarified, creates a broader understanding of the seventeenth century Englishman. An introduction develops a brief summarization of Pre-Reformation Europe, the forces which brought changes, Reformation Europe and the Post-Reformation era in which Cromwell lived. The non-Cromwellian periods were included to develop a broader picture for the reader of the atmosphere into which Cromwell emerged. The study concentrates on six key points of conflict within the lifetime of Cromwell and discussion ofthose conflicts through use of periods or roles within his life. Cromwell's changeable nature does not lend itselfto a static, one-dimensional interpretation, but rather to one that attempts to incorporate the normal fluctuations of human nature and the continuity of change. -

Contextual Information Timelines and Family Trees Tudors to Windsors: British Royal Portraits 16 March – 14 July 2019

16 March — 14 July 2019 British Royal Portraits Exhibition organised by the National Portrait Gallery, London Contextual Information Timelines and Family Trees Tudors to Windsors: British Royal Portraits 16 March – 14 July 2019 Tudors to Windsors traces the history of the British monarchy through the outstanding collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London. This exhibition highlights major events in British (and world) history from the sixteenth century to the present, examining the ways in which royal portraits were impacted by both the personalities of individual monarchs and wider historical change. Presenting some of the most significant royal portraits, the exhibition will explore five royal dynasties: the Tudors, the Stuarts, the Georgians, the Victorians and the Windsors shedding light on key figures and important historical moments. This exhibition also offers insight into the development of British art including works by the most important artists to have worked in Britain, from Sir Peter Lely and Sir Godfrey Kneller to Cecil Beaton and Annie Leibovitz. 2 UK WORLDWIDE 1485 Henry Tudor defeats Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field, becoming King Henry VII The Tudors and founding the Tudor dynasty 1492 An expedition led by Italian explorer Christopher Columbus encounters the Americas 1509 while searching for a Western passage to Asia Henry VII dies and is succeeded Introduction by King Henry VIII 1510 The Inca abandon the settlement of Machu Picchu in modern day Peru Between 1485 and 1603, England was ruled by 1517 Martin Luther nails his 95 theses to the five Tudor monarchs. From King Henry VII who won the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, crown in battle, to King Henry VIII with his six wives and a catalyst for the Protestant Reformation 1519 Elizabeth I, England’s ‘Virgin Queen’, the Tudors are some Hernando Cortes lands on of the most familiar figures in British history. -

History Term 4

History: Why were Kings back in Fashion by 1660? Year 7 Term 4 Timeline Key Terms Key Questions 1625 Charles I becomes King of England. Civil War A war between people of the same country. What Caused the English Civil War? The Divine Right of Kings — Charles I felt that God had given him Charles closes Parliament. The Eleven Years of This is a belief that the King or Queen is the most 1629 Divine Right of the power to rule and so Parliament should follow his leadership. Tyranny begin. powerful person on earth as God put them into Kings Parliament disagreed with the King over the Divine Right of Kings. power. Parliament believed it should have an important role in running the Charles reopens Parliament in order to raise 1640 country. money for war. Parliament tried to limit the King’s power. Charles responded by Eleven Years Charles I ruled England without Parliament for declaring war on Parliament in 1642. Tyranny eleven years. Charles I attempts to arrest 5 members of 1642 parliament. The English Civil War begins. Why did Parliament Win the War? A government where a King or Queen is the Head of Monarchy 1644 Parliamentarians win the Battle of Marston Moor. State. The New Model Army was created by Parliamentarians in 1645. These soldiers were paid for their services and trained well. 1645 Parliamentarians win the Battle of Naseby. A group in the UK elected by the people. They have Parliament had more money. They controlled the south of England Parliament which was much richer in resources. -

Schuler Dissertation Final Document

COUNSEL, POLITICAL RHETORIC, AND THE CHRONICLE HISTORY PLAY: REPRESENTING COUNCILIAR RULE, 1588-1603 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Anne-Marie E. Schuler, B.M., M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor Richard Dutton, Advisor Professor Luke Wilson Professor Alan B. Farmer Professor Jennifer Higginbotham Copyright by Anne-Marie E. Schuler 2011 ABSTRACT This dissertation advances an account of how the genre of the chronicle history play enacts conciliar rule, by reflecting Renaissance models of counsel that predominated in Tudor political theory. As the texts of Renaissance political theorists and pamphleteers demonstrate, writers did not believe that kings and queens ruled by themselves, but that counsel was required to ensure that the monarch ruled virtuously and kept ties to the actual conditions of the people. Yet, within these writings, counsel was not a singular concept, and the work of historians such as John Guy, Patrick Collinson, and Ann McLaren shows that “counsel” referred to numerous paradigms and traditions. These theories of counsel were influenced by a variety of intellectual movements including humanist-classical formulations of monarchy, constitutionalism, and constructions of a “mixed monarchy” or a corporate body politic. Because the rhetoric of counsel was embedded in the language that men and women used to discuss politics, I argue that the plays perform a kind of cultural work, usually reserved for literature, that reflects, heightens, and critiques political life and the issues surrounding conceptions of conciliar rule. -

Mapmaking in England, Ca. 1470–1650

54 • Mapmaking in England, ca. 1470 –1650 Peter Barber The English Heritage to vey, eds., Local Maps and Plans from Medieval England (Oxford: 1525 Clarendon Press, 1986); Mapmaker’s Art for Edward Lyman, The Map- world maps maker’s Art: Essays on the History of Maps (London: Batchworth Press, 1953); Monarchs, Ministers, and Maps for David Buisseret, ed., Mon- archs, Ministers, and Maps: The Emergence of Cartography as a Tool There is little evidence of a significant cartographic pres- of Government in Early Modern Europe (Chicago: University of Chi- ence in late fifteenth-century England in terms of most cago Press, 1992); Rural Images for David Buisseret, ed., Rural Images: modern indices, such as an extensive familiarity with and Estate Maps in the Old and New Worlds (Chicago: University of Chi- use of maps on the part of its citizenry, a widespread use cago Press, 1996); Tales from the Map Room for Peter Barber and of maps for administration and in the transaction of busi- Christopher Board, eds., Tales from the Map Room: Fact and Fiction about Maps and Their Makers (London: BBC Books, 1993); and TNA ness, the domestic production of printed maps, and an ac- for The National Archives of the UK, Kew (formerly the Public Record 1 tive market in them. Although the first map to be printed Office). in England, a T-O map illustrating William Caxton’s 1. This notion is challenged in Catherine Delano-Smith and R. J. P. Myrrour of the Worlde of 1481, appeared at a relatively Kain, English Maps: A History (London: British Library, 1999), 28–29, early date, no further map, other than one illustrating a who state that “certainly by the late fourteenth century, or at the latest by the early fifteenth century, the practical use of maps was diffusing 1489 reprint of Caxton’s text, was to be printed for sev- into society at large,” but the scarcity of surviving maps of any descrip- 2 eral decades. -

BUTLER FAMILY HISTORY the Butler Family

BUTLER FAMILY HISTORY The Butler Family,(de Butler in Gaelic and French), whose name comes from the French word "bouteleur" or "butler" is a noble family of Anglo-Norman origin, famous in the history of Ireland, where she was established in 1206. It is the only one comparable to the Geraldine, who was its neighbor and her worst rival. The Butler family is the 20th oldest subsisting aristocratic family in France,and one of the oldest in England and Ireland,dating back to the Norman conquest by William the Conqueror. She has many existing branches, not only in the UK but also in France, Spain,Germany and America. Origin and history The Butler family, which is believed to be of the family of the Counts of Brionnel arrived in England with William the Conqueror in 1066 during the Norman conquest,and received many lands and titles after participating in the Battle of Hastings. It has a proven lineage that begins with Hervey Gaultier, who owned the manor of Newton in Suffolk at the time of King Henry II (1154-1189). From the large survey of 1212, he had married in 1160 his son Walteri or Galtier Matilda or Maud, daughter of Thibaud de Valognes, who became lord of Parham to Plomesgate in Suffolk County and whose sister had married Berthe Ranulf Glanville, chief justice of the king. There are three known sons, Hubert, Archbishop of Canterbury in 1193, Rotgier, Hamo and Theobald (1206). The latter became Grand Bouteiller (or "boteleur"),an hereditary office which will give the family name "Butler".