Remembering King Charles I: History, Art and Polemics from the Restoration to the Reform Act T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War of Roses: a House Divided

Stanford Model United Nations Conference 2014 War of Roses: A House Divided Chairs: Teo Lamiot, Gabrielle Rhoades Assistant Chair: Alyssa Liew Crisis Director: Sofia Filippa Table of Contents Letters from the Chairs………………………………………………………………… 2 Letter from the Crisis Director………………………………………………………… 4 Introduction to the Committee…………………………………………………………. 5 History and Context……………………………………………………………………. 5 Characters……………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Topics on General Conference Agenda…………………………………..……………. 9 Family Tree ………………………………………………………………..……………. 12 Special Committee Rules……………………………………………………………….. 13 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………. 14 Letters from the Chairs Dear Delegates, My name is Gabrielle Rhoades, and it is my distinct pleasure to welcome you to the Stanford Model United Nations Conference (SMUNC) 2014 as members of the The Wars of the Roses: A House Divided Joint Crisis Committee! As your Wars of the Roses chairs, Teo Lamiot and I have been working hard with our crisis director, Sofia Filippa, and SMUNC Secretariat members to make this conference the best yet. If you have attended SMUNC before, I promise that this year will be even more full of surprise and intrigue than your last conference; if you are a newcomer, let me warn you of how intensely fun and challenging this conference will assuredly be. Regardless of how you arrive, you will all leave better delegates and hopefully with a reinvigorated love for Model UN. My own love for Model United Nations began when I co-chaired a committee for SMUNC (The Arab Spring), which was one of my very first experiences as a member of the Society for International Affairs at Stanford (the umbrella organization for the MUN team), and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Later that year, I joined the intercollegiate Model United Nations team. -

Paper 2: Power: Monarchy and Democracy in Britain C1000-2014

Paper 2: Power: Monarchy and democracy in Britain c1000-2014. 1. Describe the Anglo-Saxon system of government. [4] • Witan –The relatives of the King, the important nobles (Earls) and churchmen (Bishops) made up the Kings council which was known as the WITAN. These men led the armies and ruled the shires on behalf of the king. In return, they received wealth, status and land. • At local level the lesser nobles (THEGNS) carried out the roles of bailiffs and estate management. Each shire was divided into HUNDREDS. These districts had their own law courts and army. • The Church handled many administrative roles for the King because many churchmen could read and write. The Church taught the ordinary people about why they should support the king and influence his reputation. They also wrote down the history of the period. 2. Explain why the Church was important in Anglo-Saxon England. [8] • The church was flourishing in Aethelred’s time (c.1000). Kings and noblemen gave the church gifts of land and money. The great MINSTERS were in Rochester, York, London, Canterbury and Winchester. These Churches were built with donations by the King. • Nobles provided money for churches to be built on their land as a great show of status and power. This reminded the local population of who was in charge. It hosted community events as well as religious services, and new laws or taxes would be announced there. Building a church was the first step in building a community in the area. • As churchmen were literate some of the great works of learning, art and culture. -

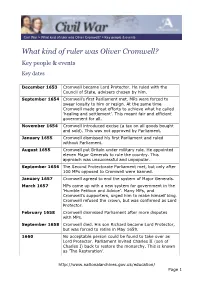

What Kind of Ruler Was Oliver Cromwell? > Key People & Events

Civil War > What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? > Key people & events What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? Key people & events Key dates December 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector. He ruled with the Council of State, advisers chosen by him. September 1654 Cromwell’s first Parliament met. MPs were forced to swear loyalty to him or resign. At the same time Cromwell made great efforts to achieve what he called ‘healing and settlement’. This meant fair and efficient government for all. November 1654 Cromwell introduced excise (a tax on all goods bought and sold). This was not approved by Parliament. January 1655 Cromwell dismissed his first Parliament and ruled without Parliament. August 1655 Cromwell put Britain under military rule. He appointed eleven Major Generals to rule the country. This approach was unsuccessful and unpopular. September 1656 The Second Protectorate Parliament met, but only after 100 MPs opposed to Cromwell were banned. January 1657 Cromwell agreed to end the system of Major Generals. March 1657 MPs came up with a new system for government in the ‘Humble Petition and Advice’. Many MPs, and Cromwell’s supporters, urged him to make himself king. Cromwell refused the crown, but was confirmed as Lord Protector. February 1658 Cromwell dismissed Parliament after more disputes with MPs. September 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was forced to retire in May 1659. 1660 No acceptable person could be found to take over as Lord Protector. Parliament invited Charles II (son of Charles I) back to restore the monarchy. This is known as ‘The Restoration’. -

Why Did Britain Become a Republic? > New Government

Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Why did Britain become a republic? Case study 2: New government Even today many people are not aware that Britain was ever a republic. After Charles I was put to death in 1649, a monarch no longer led the country. Instead people dreamed up ideas and made plans for a different form of government. Find out more from these documents about what happened next. Report on the An account of the Poem on the arrest of setting up of the new situation in Levellers, 1649 Commonwealth England, 1649 Portrait & symbols of Cromwell at the The setting up of Cromwell & the Battle of the Instrument Commonwealth Worcester, 1651 of Government http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Page 1 Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Case study 2: New government - Source 1 A report on the arrest of some Levellers, 29 March 1649 (Catalogue ref: SP 25/62, pp.134-5) What is this source? This is a report from a committee of MPs to Parliament. It explains their actions against the leaders of the Levellers. One of the men they arrested was John Lilburne, a key figure in the Leveller movement. What’s the background to this source? Before the war of the 1640s it was difficult and dangerous to come up with new ideas and try to publish them. However, during the Civil War censorship was not strongly enforced. Many political groups emerged with new ideas at this time. One of the most radical (extreme) groups was the Levellers. -

Pierce, Helen. "Text and Image: William Marshall's Frontispiece to the Eikon Basilike (1649)." Censorship Moments: R

Pierce, Helen. "Text and Image: William Marshall’s Frontispiece to the Eikon Basilike (1649)." Censorship Moments: Reading Texts in the History of Censorship and Freedom of Expression. Ed. Geoff Kemp. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015. 79–86. Textual Moments in the History of Political Thought. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 6 May 2019. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472593078.ch-011>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 6 May 2019, 11:54 UTC. Copyright © Geoff Kemp and contributors 2015. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher. 10 Text and Image: William Marshall’s Frontispiece to the Eikon Basilike (1649) Helen Pierce © The Trustees of the British Museum On the morning of 30 January 1649, King Charles I of England stepped out of the Banqueting House on London’s Whitehall and onto a hastily assembled scaffold dominated by the executioner’s block. One onlooker reported that as the king’s head was separated from his body, ‘there was such a grone by the thousands then present as I never heard before and desire I may never hear 80 Censorship Moments again’; subsequent images of the scene produced in print and paint show members of the crowd weeping and fainting, as others reach forwards to salvage drops of the king’s blood as precious relics.1 The shaping of Charles’s posthumous reputation as royal martyr may appear to have originated with the relic-hunters at the scaffold, but both its catalyst and its fuel was the publication of a book. -

John Denham: New Letters and Documents

JOHN DENHAM: NEW LETTERS AND DOCUMENTS HILTON KELLIHER IT was inevitable that the fundamental divisions made in English society by the Civil Wars should affect the ranks of the poets and playwrights, and unsurprising that the former largely and the latter almost entirely would adhere to the king's party. Not that, from our more distant vantage-point at least, the literary advantage lay with the larger faction. When the lines were drawn the Parliamentarians could muster Milton, Marvell, the young Dryden, and, proximum longo intervalloj the elderly George Wither, who had done his best work in the reign of James L Edmund Waller occupied an unenviable position between the two camps; while Cowley, Denham, Fanshawe, Lovelace, Quarks, and Suckling, along with the dramatists Davenant, the two Killigrews and Shirley, are the most notable of those who either served Charles I or his successor in exile or suffered directly on their behalf. Among the latter party John Denham (fig. i) occupied in political terms a moderately distinguished place, acting as agent at home and as envoy abroad to both Charles Stuarts in turn. As a poet he is chiefly remembered as the author of Cooper^s Hill^ the first great topographical poem in the language, and he is sometimes said to be the one who did most to promote the transition of English verse from the Metaphysical to the Augustan mode. The purpose of the present rather disjointed notes is to supplement the very different but equally indispensable accounts given by his earliest biographer, John Aubrey,^ and his latest, Brendan O'Hehir,^ with some letters and documents that have recently come to light, more especially relating to his life in exile on the Continent between September 1648 and March 1653. -

The Significance of Satan: Eikonoklastes As a Guide to Reading the Character in Milton’S Paradise Lost

1 The Significance of Satan: Eikonoklastes as a Guide to Reading the Character in Milton’s Paradise Lost Emily Chow May 2012 Submitted to the Department of English at Mount Holyoke College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors. 2 Acknowledgements It is with utmost gratitude that I acknowledge and thank the following individuals who have played a role in shaping my thesis: Firstly, my academic and thesis advisor, Professor Eugene Hill, who introduced me to Milton and whose intellect and guidance proved invaluable throughout my thesis writing. All of this would not have been possible without you. To Professor Bill Quillian and Professor Nadia Margolis, many thanks for being on my defense committee. Additionally, thank you to Professor Heidi Holder as well for helping with the thesis edits. To LITS Liason Mary Stettner, my greatest appreciation for your help with references, citations, your patience and prompt email replies. To Miss Caroline, for teaching a plebeian the meaning of “plebeian.” To all of the amazing people who are my friends – of those here at Mount Holyoke to those scattered across the world from Canada to Australia, to the one who listened to my symposium presentation and the Little One who explained the Bible to me the best she could, from the one I’ve enjoyed conversations over beer and peanuts with to the one who kept me company online throughout those late nights, and finally to the one who indulged me with some Emily Chow time when it was much needed – I extend my sincerest and most heartfelt thank-yous. -

A History of the French in London Liberty, Equality, Opportunity

A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity Edited by Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity Edited by Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU First published in print in 2013. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978 1 909646 48 3 (PDF edition) ISBN 978 1 905165 86 5 (hardback edition) Contents List of contributors vii List of figures xv List of tables xxi List of maps xxiii Acknowledgements xxv Introduction The French in London: a study in time and space 1 Martyn Cornick 1. A special case? London’s French Protestants 13 Elizabeth Randall 2. Montagu House, Bloomsbury: a French household in London, 1673–1733 43 Paul Boucher and Tessa Murdoch 3. The novelty of the French émigrés in London in the 1790s 69 Kirsty Carpenter Note on French Catholics in London after 1789 91 4. Courts in exile: Bourbons, Bonapartes and Orléans in London, from George III to Edward VII 99 Philip Mansel 5. The French in London during the 1830s: multidimensional occupancy 129 Máire Cross 6. Introductory exposition: French republicans and communists in exile to 1848 155 Fabrice Bensimon 7. -

Cover Hubert Le Sueur Hercules and Telephus.Indd

benjamin proust fine art limited london benjamin proust fine art limited london attributed to HUBERT LE SUEUR Paris, 1580–1658 hercules and telephus circa 1630 Bronze 39.4 x 15.9 x 12.4 cm Inventory mark ‘8’ in red paint on lion skin tail provenance Most probably, François Le Vau (1613–1676), ‘Maison du Centaure’, 45 Quai de Bourbon, Paris, until his death; Most probably, Louis, Grand Dauphin de France (1661–1711), Château de Versailles, from at least 1689 and until his death, when sold; Most probably, Jean-Baptiste, Count du Barry (1723–1794), Paris; His sale, 21 November 1774, lot 142; Noble private collection, Provence, France, until 2017 comparative literature F. Souchal, Les Frères Coustou, Paris, 1980 G. Bresc-Bautier, ‘L’activité parisienne d’Hubert Le Sueur sculpteur du roi (connu de 1596 à 1658)’, in Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire de l’art français, 1985, pp. 35–54 C. Avery, ‘Hubert Le Sueur, the ‘Unworthy Praxiteles’ of King Charles I’, in Studies in European Sculpture II, London, 1988, pp. 145–235 J. Chlibec, ‘Small Italian Renaissance Bronzes in the Collection of the National Gallery in Prague’, in Bulletin of the National Gallery in Prague, III-IV (1993–94), pp. 36–52 A. Gallottini (ed.), ‘Philippe Thomassin: Antiquarum Statuarum Urbis Romae Liber Primus (1610–1622)’, in Bollettino d’Arte, 1995, pp. 21–23 S. Castelluccio, ‘La Collection de bronzes du Grand Dauphin’, in Curiosité: Édutes d’histoire de l’art en l’honneur d’Antoine Schnapper, Paris, 1998, pp. 355–63 S. Baratte, G. Bresc-Bautier et al., Les Bronzes de la Couronne, exh. -

Andrew Marvell Newsletter | Vol

Andrew Marvell Newsletter | Vol. 6, No. 2 | Winter 2014 THE INSTABILITY OF MARVELL’S BERMUDAS BY TIMOTHY RAYLOR I How should we take Bermudas?1 Is it a straightforward propaganda poem, commemorating the commencement of the godly governorship of the newly appointed Somers Island commissioner and erstwhile colonist, John Oxenbridge? Or is the poem shot through with doubts and questions—with ironies that call into question the actions and purity of motive of its singing rowers? Both positions have been urged: the former especially in the nineteenth century, when Marvell came first to critical notice; the latter more commonly in the twentieth. The eighth edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1853-60), for example, cited the poem approvingly as “one of the finest strains of the Puritan muse.”2 But in the twentieth century challenges to the propagandistic reading came from two directions. One was the New Criticism, with its tendency to read any narrative frame, any instance of playful wit, as debilitating irony—an approach to which the poem lends ample ammunition. The second direction was historical. As the early history of the Bermuda colony came to be better understood, the gap between that history—natural, economic, and religious—and Marvell’s poetic recreation of it came to appear so pointed as to be explainable only in terms of an ironic counter-narrative.3 From the natural and economic historical points of view, high hopes of vast resources were soon dashed. From the point of view of religion, the colony was not predominantly or even notably Puritan, and although we find a small tradition of Puritan ministers, including Oxenbridge himself, making their way there during the century, the Bermudas were settled in the first instance largely by economic migrants. -

Poetical Works of Edmund Waller and Sir John Denham

Poetical Works of Edmund Waller and Sir John Denham Edmund Waller; John Denham The Project Gutenberg EBook of Poetical Works of Edmund Waller and Sir John Denham, by Edmund Waller; John Denham This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Poetical Works of Edmund Waller and Sir John Denham Author: Edmund Waller; John Denham Release Date: May 10, 2004 [EBook #12322] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK POETICAL WORKS *** Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Carol David and PG Distributed Proofreaders POETICAL WORKS OF EDMUND WALLER AND SIR JOHN DENHAM. WITH MEMOIR AND DISSERTATION, BY THE REV. GEORGE GILFILLAN. M.DCCC.LVII. Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. THE LIFE OF EDMUND WALLER. It is too true, after all, that the lives of poets are not, in general, very interesting. Could we, indeed, trace the private workings of their souls, and read the pages of their mental and moral development, no biographies could be richer in instruction, and even entertainment, than those of our greater bards. The inner life of every true poet must be poetical. But in proportion to the romance of their souls' story, is often the commonplace of their outward career. There have been poets, however, whose lives are quite as readable and as instructive as their poetry, and have even shed a reflex and powerful interest on their writings. -

I. Milton's Library

John Milton and the Cultures of Print An Exhibition of Books, Manuscripts, and Other Artifacts February 3, 2011 – May 31, 2011 Rutgers University Libraries Special Collections and University Archives Alexander Library Rutgers University Thomas Fulton Published by Rutgers University Libraries Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey New Brunswick, NJ John Milton at the age of 62, in The hisTory of BriTain (1670), by the english engraver WilliaM faithorne, taken froM life. Cover illustration: illustration by WilliaM blake froM Blake, MilTon a poeM (1804) Table of Contents Introduction . 1 I Milton’s Library . 3 II Milton’s Early Poetry . 7 III The Scribal Publication of Verse . 10 IV Pamphlet Wars . 12 V Divorce Tracts . 14 VI Revolution and the Freedom of the Press . 16 VII The Execution of Charles I . 19 VIII Milton and Sons: A Family Business . 22 IX The Restoration: Censorship and Paradise Lost . 23 X The Christian Doctrine . 26 XI Censorship and Milton’s Late Work . 27 XII J . Milton French: A Tribute . 29 Acknowledgements . 30 This exhibition was made possible by a grant from the New Jersey Council for the Humanities, a state partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities . Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations in the exhibition do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities or the New Jersey Council for the Humanities . ntroduction John Milton was born in 1608 to a century of revolution — in politics, in print media, in science and the arts . By the time he died in 1674, Britain had experienced the governments of three different Stuart monarchs, the protectorate of Oliver Cromwell, and a few short-lived experiments in republican government .