Anglo-Saxons and English Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Liberty in England and Revolutionary America

P1: IwX/KaD 0521827450agg.xml CY395B/Ward 0 521 82745 0 May 7, 2004 7:37 The Politics of Liberty in England and Revolutionary America LEE WARD Campion College University of Regina iii P1: IwX/KaD 0521827450agg.xml CY395B/Ward 0 521 82745 0 May 7, 2004 7:37 published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Lee Ward 2004 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2004 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Sabon 10/12 pt. System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Ward, Lee, 1970– The politics of liberty in England and revolutionary America / Lee Ward p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. isbn 0-521-82745-0 1. Political science – Great Britain – Philosophy – History – 17th century. 2. Political science – Great Britain – Philosophy – History – 18th century. 3. Political science – United States – Philosophy – History – 17th century. 4. Political science – United States – Philosophy – History – 18th century. 5. United States – History – Revolution, 1775–1783 – Causes. -

Paper 2: Power: Monarchy and Democracy in Britain C1000-2014

Paper 2: Power: Monarchy and democracy in Britain c1000-2014. 1. Describe the Anglo-Saxon system of government. [4] • Witan –The relatives of the King, the important nobles (Earls) and churchmen (Bishops) made up the Kings council which was known as the WITAN. These men led the armies and ruled the shires on behalf of the king. In return, they received wealth, status and land. • At local level the lesser nobles (THEGNS) carried out the roles of bailiffs and estate management. Each shire was divided into HUNDREDS. These districts had their own law courts and army. • The Church handled many administrative roles for the King because many churchmen could read and write. The Church taught the ordinary people about why they should support the king and influence his reputation. They also wrote down the history of the period. 2. Explain why the Church was important in Anglo-Saxon England. [8] • The church was flourishing in Aethelred’s time (c.1000). Kings and noblemen gave the church gifts of land and money. The great MINSTERS were in Rochester, York, London, Canterbury and Winchester. These Churches were built with donations by the King. • Nobles provided money for churches to be built on their land as a great show of status and power. This reminded the local population of who was in charge. It hosted community events as well as religious services, and new laws or taxes would be announced there. Building a church was the first step in building a community in the area. • As churchmen were literate some of the great works of learning, art and culture. -

Swivel-Eyed Loons Had Found Their Cheerleader at Last: Like Nobody Else, Boris Could Put a Jolly Gloss on Their Ugly Tale of Brexit As Cultural Class- War

DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, MCQs, Magazines www.thecsspoint.com Download CSS Notes Download CSS Books Download CSS Magazines Download CSS MCQs Download CSS Past Papers The CSS Point, Pakistan’s The Best Online FREE Web source for All CSS Aspirants. Email: [email protected] BUY CSS / PMS / NTS & GENERAL KNOWLEDGE BOOKS ONLINE CASH ON DELIVERY ALL OVER PAKISTAN Visit Now: WWW.CSSBOOKS.NET For Oder & Inquiry Call/SMS/WhatsApp 0333 6042057 – 0726 540141 FPSC Model Papers 50th Edition (Latest & Updated) By Imtiaz Shahid Advanced Publishers For Order Call/WhatsApp 03336042057 - 0726540141 CSS Solved Compulsory MCQs From 2000 to 2020 Latest & Updated Order Now Call/SMS 03336042057 - 0726540141 Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power & Peace By Hans Morgenthau FURTHER PRAISE FOR JAMES HAWES ‘Engaging… I suspect I shall remember it for a lifetime’ The Oldie on The Shortest History of Germany ‘Here is Germany as you’ve never known it: a bold thesis; an authoritative sweep and an exhilarating read. Agree or disagree, this is a must for anyone interested in how Germany has come to be the way it is today.’ Professor Karen Leeder, University of Oxford ‘The Shortest History of Germany, a new, must-read book by the writer James Hawes, [recounts] how the so-called limes separating Roman Germany from non-Roman Germany has remained a formative distinction throughout the post-ancient history of the German people.’ Economist.com ‘A daring attempt to remedy the ignorance of the centuries in little over 200 pages... not just an entertaining canter -

Cromwelliana 2012

CROMWELLIANA 2012 Series III No 1 Editor: Dr Maxine Forshaw CONTENTS Editor’s Note 2 Cromwell Day 2011: Oliver Cromwell – A Scottish Perspective 3 By Dr Laura A M Stewart Farmer Oliver? The Cultivation of Cromwell’s Image During 18 the Protectorate By Dr Patrick Little Oliver Cromwell and the Underground Opposition to Bishop 32 Wren of Ely By Dr Andrew Barclay From Civilian to Soldier: Recalling Cromwell in Cambridge, 44 1642 By Dr Sue L Sadler ‘Dear Robin’: The Correspondence of Oliver Cromwell and 61 Robert Hammond By Dr Miranda Malins Mrs S C Lomas: Cromwellian Editor 79 By Dr David L Smith Cromwellian Britain XXIV : Frome, Somerset 95 By Jane A Mills Book Reviews 104 By Dr Patrick Little and Prof Ivan Roots Bibliography of Books 110 By Dr Patrick Little Bibliography of Journals 111 By Prof Peter Gaunt ISBN 0-905729-24-2 EDITOR’S NOTE 2011 was the 360th anniversary of the Battle of Worcester and was marked by Laura Stewart’s address to the Association on Cromwell Day with her paper on ‘Oliver Cromwell: a Scottish Perspective’. ‘Risen from Obscurity – Cromwell’s Early Life’ was the subject of the study day in Huntingdon in October 2011 and three papers connected with the day are included here. Reflecting this subject, the cover illustration is the picture ‘Cromwell on his Farm’ by Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893), painted in 1874, and reproduced here courtesy of National Museums Liverpool. The painting can be found in the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight Village, Wirral, Cheshire. In this edition of Cromwelliana, it should be noted that the bibliography of journal articles covers the period spring 2009 to spring 2012, addressing gaps in the past couple of years. -

Steven CA Pincus James A. Robinson Working Pape

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES WHAT REALLY HAPPENED DURING THE GLORIOUS REVOLUTION? Steven C.A. Pincus James A. Robinson Working Paper 17206 http://www.nber.org/papers/w17206 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 July 2011 This paper was written for Douglass North’s 90th Birthday celebration. We would like to thank Doug, Daron Acemoglu, Stanley Engerman, Joel Mokyr and Barry Weingast for their comments and suggestions. We are grateful to Dan Bogart, Julian Hoppit and David Stasavage for providing us with their data and to María Angélica Bautista and Leslie Thiebert for their superb research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2011 by Steven C.A. Pincus and James A. Robinson. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. What Really Happened During the Glorious Revolution? Steven C.A. Pincus and James A. Robinson NBER Working Paper No. 17206 July 2011 JEL No. D78,N13,N43 ABSTRACT The English Glorious Revolution of 1688-89 is one of the most famous instances of ‘institutional’ change in world history which has fascinated scholars because of the role it may have played in creating an environment conducive to making England the first industrial nation. -

The Complexities of Whig and Tory Anti-Catholicism in Late Seventeenth-Century England

THE COMPLEXITIES OF WHIG AND TORY ANTI-CATHOLICISM IN LATE SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND By Matthew L. Levine, B.A. Misericordia University A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History to the Office of Graduate and Extended Studies of East Stroudsburg University of Pennsylvania December 14, 2019 ABSTRACT A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History to the Office of Graduate and Extended Studies of East Stroudsburg University of Pennsylvania Student’s Name: Matthew Levine Title: The Complexities of Whig and Tory Anti-Catholicism in Late Seventeenth-Century England Date of Graduation: December 14, 2019 Thesis Chair: Christopher Dudley, Ph.D. Thesis Member: Shannon Frystak, Ph.D. Abstract The purpose of my research is to analyze anti-Catholicism in late seventeenth-century England in order to comprehend how complex it was. I analyzed primary (published) sources such as dialogues, diaries, histories, letters, pamphlets, royal proclamations, and sermons to get my results. Based on this research, I argue that Whiggish anti-Catholicism remained mostly static over time, while the Toryish variant changed in four different ways; this reflected each party’s different approach to anti-Catholicism. The Whigs focused on Francophobia, the threat that Catholicism posed to Protestant liberties, and toleration of all Protestants, while the Tories focused on loyalty to Anglicanism and the threat that Catholics and Dissenters posed to Anglicanism. While the Whigs did not change with different contexts, the Tories did so four times. The significance is that, while the core principles might have remained fairly static, the presentation and impact of those ideas changed with different circumstances. -

Grant Tapsell.Pdf (49.35Kb)

62 SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NEWS tional, if unstable, fantasy of reaffirmed loyalty to and (at the same time) escape from the traditions and authority attributed, out of filial-piety, to a venerated first generation of Puritan leaders. The Captive’s Position has been years in the making, with remarkable results. It meaningfully engages a wide range of pertinent prior scholarly work by others, and its uncommonly lucid sentences are crafted with care and skill. It is a book that takes the reader deeply into the investigative ruminations and convictions of its author but also, as in all good teaching, proceeds in a man- ner designed with an audience in mind. Toulouse’s opening question, implying a Newtonian world of simple cause and effect, gives way to a more subtle and complex encounter with hard-to-pin-down motives which necessarily remain as elusive as sub-atomic eventuation. The result, however, is a provocative psycho-cultural interpreta- tion comprised of diverse particles–historical details, circumstantial associa- tions and hypothetical propositions–strategically and imaginatively combined to convey a plausible cause-and-effect finale. Grant Tapsell. The Personal Rule of Charles II, 1681-85. Woodbridge and Rochester: Boydell, 2007. $90.00. Review by MOLLY MCCLAIN, UNIVERSITY OF SAN DIEGO. A more accurate title for this book would be “Whigs and Tories after the Exclusion Crisis.” Grant Tapsell does not deal with King Charles II as a historical figure nor does he pay much attention to “personal monarchy” as a concept. Instead, he provides a survey of political opinion in the early 1680s, relying heavily on the work of Tim Harris, Mark Knights, and Jonathan Scott. -

S. N. S. College, Jehanabad

S. N. S. COLLEGE, JEHANABAD (A Constituent unit of Magadh University, Bodh Gaya) DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY KEY-NOTES JAMES-I (1603-1625) FOR B.A. PART – I BY KRITI SINGH ANAND, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR, DEPTT. OF HISTORY, S.N. SINHA COLLEGE, JEHANABAD 1 James I (1603 - 1625) James VI King of Scotland was the great grandson of Margaret, the daughter of HenryVIII of England. The accession of James Stuart to the English throne as James I, on the death of Elizabeth in 1603, brought about the peaceful union of the rival monarchies of England and Scotland. He tried to make the union of two very different lands complete by assuming the title of King of Great Britain. There was peace in England and people did not fear any danger from a disputed succession inside the country or from external aggression. So strong monarchy was not considered essential for the welfare of the people. Even towards the end of the reign of Queen Elizabeth, Parliament began to oppose the royal will. The attempts of the new king to make the two lands to have one parliament, one church and one law failed miserably, because the Scots were not interested in the union and the English Parliament did not co- operate with him for it did not trust him. James I had experience as the King of Scotland and he knew very well the history of the absolute rule of the Tudor monarchs in England. So he was determined to rule with absolute powers. He believed in the theory of Divine Right Kingship and his own accession to the English throne was sanctioned by this theory. -

The English Civil Wars a Beginner’S Guide

The English Civil Wars A Beginner’s Guide Patrick Little A Oneworld Paperback Original Published in North America, Great Britain and Australia by Oneworld Publications, 2014 Copyright © Patrick Little 2014 The moral right of Patrick Little to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him/her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved Copyright under Berne Convention A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library ISBN 9781780743318 eISBN 9781780743325 Typeset by Siliconchips Services Ltd, UK Printed and bound in Denmark by Nørhaven A/S Oneworld Publications 10 Bloomsbury Street London WC1B 3SR England Stay up to date with the latest books, special offers, and exclusive content from Oneworld with our monthly newsletter Sign up on our website www.oneworld-publications.com Contents Preface vii Map of the English Civil Wars, 1642–51 ix 1 The outbreak of war 1 2 ‘This war without an enemy’: the first civil war, 1642–6 17 3 The search for settlement, 1646–9 34 4 The commonwealth, 1649–51 48 5 The armies 66 6 The generals 82 7 Politics 98 8 Religion 113 9 War and society 126 10 Legacy 141 Timeline 150 Further reading 153 Index 157 Preface In writing this book, I had two primary aims. The first was to produce a concise, accessible account of the conflicts collectively known as the English Civil Wars. The second was to try to give the reader some idea of what it was like to live through that trau- matic episode. -

Contextual Information Timelines and Family Trees Tudors to Windsors: British Royal Portraits 16 March – 14 July 2019

16 March — 14 July 2019 British Royal Portraits Exhibition organised by the National Portrait Gallery, London Contextual Information Timelines and Family Trees Tudors to Windsors: British Royal Portraits 16 March – 14 July 2019 Tudors to Windsors traces the history of the British monarchy through the outstanding collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London. This exhibition highlights major events in British (and world) history from the sixteenth century to the present, examining the ways in which royal portraits were impacted by both the personalities of individual monarchs and wider historical change. Presenting some of the most significant royal portraits, the exhibition will explore five royal dynasties: the Tudors, the Stuarts, the Georgians, the Victorians and the Windsors shedding light on key figures and important historical moments. This exhibition also offers insight into the development of British art including works by the most important artists to have worked in Britain, from Sir Peter Lely and Sir Godfrey Kneller to Cecil Beaton and Annie Leibovitz. 2 UK WORLDWIDE 1485 Henry Tudor defeats Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field, becoming King Henry VII The Tudors and founding the Tudor dynasty 1492 An expedition led by Italian explorer Christopher Columbus encounters the Americas 1509 while searching for a Western passage to Asia Henry VII dies and is succeeded Introduction by King Henry VIII 1510 The Inca abandon the settlement of Machu Picchu in modern day Peru Between 1485 and 1603, England was ruled by 1517 Martin Luther nails his 95 theses to the five Tudor monarchs. From King Henry VII who won the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, crown in battle, to King Henry VIII with his six wives and a catalyst for the Protestant Reformation 1519 Elizabeth I, England’s ‘Virgin Queen’, the Tudors are some Hernando Cortes lands on of the most familiar figures in British history. -

LOCKE STUDIES Vol

LOCKE STUDIES Vol. 18 https://doi.org/10.5206/ls.2018.6177 | ISSN: 2561-925X Submitted: 27 NOVEMBER 2018 Published online: 8 DECEMBER 2018 For more information, see this article’s homepage. © 2018. D. N. DeLuna Shaftesbury, Locke, and Their Revolutionary Letter? [Corrigendum] D. N. DELUNA (UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON) Abstract: A correction of an article originally published in vol 17 (2017). In 1675, the anonymous Letter to a Person of Quality was condemned in the House of Lords and ordered to be burned by the public hangman. A propagandistic work that has long been attributed to Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, and less certainly to his secretary John Locke, it traduced hard-line Anglican legislation considered in Parliament that year— namely the Test Bill, proposing that office-holders and MPs swear off political militancy and indeed any efforts to reform the Church and State. Careful examination of the text of the Letter, and that of one of its sources in the Reasons against the Bill for the Test, also circulated in 1675, reveals the presence of highly seditious passages of covert historical allegory. Hitherto un-noted by modern scholars, this allegory compared King Charles II to the weak and intermittently mad Henry VI, while agitating for armed revolt against a government made prey to popish and French captors. The discovery compels modification, through chronological revision and also re-assessment of the probability of Locke’s authorship of the Letter, of Richard Ashcraft’s picture of Shaftesbury and Locke as first-time revolutionaries for the cause of religious tolerance in the early 1680s. -

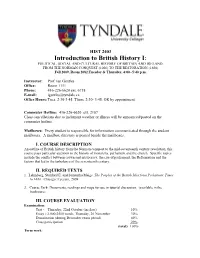

Introduction to British History I

HIST 2403 Introduction to British History I: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND, FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST (1066) TO THE RESTORATION (1660) Fall 2009, Room 2082,Tuesday & Thursday, 4:00--5:40 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Ian Gentles Office: Room 1111 Phone: 416-226-6620 ext. 6718 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:30-3:45, Thurs. 2:30- 3:45, OR by appointment Commuter Hotline: 416-226-6620 ext. 2187 Class cancellations due to inclement weather or illness will be announced/posted on the commuter hotline. Mailboxes: Every student is responsible for information communicated through the student mailboxes. A mailbox directory is posted beside the mailboxes. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION An outline of British history from the Norman conquest to the mid-seventeenth century revolution, this course pays particular attention to the history of monarchy, parliament and the church. Specific topics include the conflict between crown and aristocracy, the rise of parliament, the Reformation and the factors that led to the turbulence of the seventeenth century. II. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Lehmberg, Stanford E. and Samantha Meigs. The Peoples of the British Isles from Prehistoric Times to 1688 . Chicago: Lyceum, 2009 2. Course Pack: Documents, readings and maps for use in tutorial discussion. (available in the bookstore) III. COURSE EVALUATION Examination : Test - Thursday, 22nd October (in class) 10% Essay - 2,000-2500 words, Thursday, 26 November 30% Examination (during December exam period) 40% Class participation 20% (total) 100% Term work : a. You are expected to attend the tutorials, preparing for them through the lectures and through assigned reading.