Treason and Power in Tudor England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue of the Earl Marshal's Papers at Arundel

CONTENTS CONTENTS v FOREWORD by Sir Anthony Wagner, K.C.V.O., Garter King of Arms vii PREFACE ix LIST OF REFERENCES xi NUMERICAL KEY xiii COURT OF CHIVALRY Dated Cases 1 Undated Cases 26 Extracts from, or copies of, records relating to the Court; miscellaneous records concerning the Court or its officers 40 EARL MARSHAL Office and Jurisdiction 41 Precedence 48 Deputies 50 Dispute between Thomas, 8th Duke of Norfolk and Henry, Earl of Berkshire, 1719-1725/6 52 Secretaries and Clerks 54 COLLEGE OF ARMS General Administration 55 Commissions, appointments, promotions, suspensions, and deaths of Officers of Arms; applications for appointments as Officers of Arms; lists of Officers; miscellanea relating to Officers of Arms 62 Office of Garter King of Arms 69 Officers of Arms Extraordinary 74 Behaviour of Officers of Arms 75 Insignia and dress 81 Fees 83 Irregularities contrary to the rules of honour and arms 88 ACCESSIONS AND CORONATIONS Coronation of King James II 90 Coronation of King George III 90 Coronation of King George IV 90 Coronation of Queen Victoria 90 Coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra 90 Accession and Coronation of King George V and Queen Mary 96 Royal Accession and Coronation Oaths 97 Court of Claims 99 FUNERALS General 102 King George II 102 Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales 102 King George III 102 King William IV 102 William Ewart Gladstone 103 Queen Victoria 103 King Edward VII 104 CEREMONIAL Precedence 106 Court Ceremonial; regulations; appointments; foreign titles and decorations 107 Opening of Parliament -

War of Roses: a House Divided

Stanford Model United Nations Conference 2014 War of Roses: A House Divided Chairs: Teo Lamiot, Gabrielle Rhoades Assistant Chair: Alyssa Liew Crisis Director: Sofia Filippa Table of Contents Letters from the Chairs………………………………………………………………… 2 Letter from the Crisis Director………………………………………………………… 4 Introduction to the Committee…………………………………………………………. 5 History and Context……………………………………………………………………. 5 Characters……………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Topics on General Conference Agenda…………………………………..……………. 9 Family Tree ………………………………………………………………..……………. 12 Special Committee Rules……………………………………………………………….. 13 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………. 14 Letters from the Chairs Dear Delegates, My name is Gabrielle Rhoades, and it is my distinct pleasure to welcome you to the Stanford Model United Nations Conference (SMUNC) 2014 as members of the The Wars of the Roses: A House Divided Joint Crisis Committee! As your Wars of the Roses chairs, Teo Lamiot and I have been working hard with our crisis director, Sofia Filippa, and SMUNC Secretariat members to make this conference the best yet. If you have attended SMUNC before, I promise that this year will be even more full of surprise and intrigue than your last conference; if you are a newcomer, let me warn you of how intensely fun and challenging this conference will assuredly be. Regardless of how you arrive, you will all leave better delegates and hopefully with a reinvigorated love for Model UN. My own love for Model United Nations began when I co-chaired a committee for SMUNC (The Arab Spring), which was one of my very first experiences as a member of the Society for International Affairs at Stanford (the umbrella organization for the MUN team), and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Later that year, I joined the intercollegiate Model United Nations team. -

Paper 2: Power: Monarchy and Democracy in Britain C1000-2014

Paper 2: Power: Monarchy and democracy in Britain c1000-2014. 1. Describe the Anglo-Saxon system of government. [4] • Witan –The relatives of the King, the important nobles (Earls) and churchmen (Bishops) made up the Kings council which was known as the WITAN. These men led the armies and ruled the shires on behalf of the king. In return, they received wealth, status and land. • At local level the lesser nobles (THEGNS) carried out the roles of bailiffs and estate management. Each shire was divided into HUNDREDS. These districts had their own law courts and army. • The Church handled many administrative roles for the King because many churchmen could read and write. The Church taught the ordinary people about why they should support the king and influence his reputation. They also wrote down the history of the period. 2. Explain why the Church was important in Anglo-Saxon England. [8] • The church was flourishing in Aethelred’s time (c.1000). Kings and noblemen gave the church gifts of land and money. The great MINSTERS were in Rochester, York, London, Canterbury and Winchester. These Churches were built with donations by the King. • Nobles provided money for churches to be built on their land as a great show of status and power. This reminded the local population of who was in charge. It hosted community events as well as religious services, and new laws or taxes would be announced there. Building a church was the first step in building a community in the area. • As churchmen were literate some of the great works of learning, art and culture. -

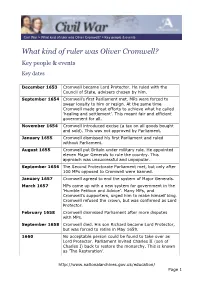

What Kind of Ruler Was Oliver Cromwell? > Key People & Events

Civil War > What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? > Key people & events What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? Key people & events Key dates December 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector. He ruled with the Council of State, advisers chosen by him. September 1654 Cromwell’s first Parliament met. MPs were forced to swear loyalty to him or resign. At the same time Cromwell made great efforts to achieve what he called ‘healing and settlement’. This meant fair and efficient government for all. November 1654 Cromwell introduced excise (a tax on all goods bought and sold). This was not approved by Parliament. January 1655 Cromwell dismissed his first Parliament and ruled without Parliament. August 1655 Cromwell put Britain under military rule. He appointed eleven Major Generals to rule the country. This approach was unsuccessful and unpopular. September 1656 The Second Protectorate Parliament met, but only after 100 MPs opposed to Cromwell were banned. January 1657 Cromwell agreed to end the system of Major Generals. March 1657 MPs came up with a new system for government in the ‘Humble Petition and Advice’. Many MPs, and Cromwell’s supporters, urged him to make himself king. Cromwell refused the crown, but was confirmed as Lord Protector. February 1658 Cromwell dismissed Parliament after more disputes with MPs. September 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was forced to retire in May 1659. 1660 No acceptable person could be found to take over as Lord Protector. Parliament invited Charles II (son of Charles I) back to restore the monarchy. This is known as ‘The Restoration’. -

Why Did Britain Become a Republic? > New Government

Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Why did Britain become a republic? Case study 2: New government Even today many people are not aware that Britain was ever a republic. After Charles I was put to death in 1649, a monarch no longer led the country. Instead people dreamed up ideas and made plans for a different form of government. Find out more from these documents about what happened next. Report on the An account of the Poem on the arrest of setting up of the new situation in Levellers, 1649 Commonwealth England, 1649 Portrait & symbols of Cromwell at the The setting up of Cromwell & the Battle of the Instrument Commonwealth Worcester, 1651 of Government http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Page 1 Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Case study 2: New government - Source 1 A report on the arrest of some Levellers, 29 March 1649 (Catalogue ref: SP 25/62, pp.134-5) What is this source? This is a report from a committee of MPs to Parliament. It explains their actions against the leaders of the Levellers. One of the men they arrested was John Lilburne, a key figure in the Leveller movement. What’s the background to this source? Before the war of the 1640s it was difficult and dangerous to come up with new ideas and try to publish them. However, during the Civil War censorship was not strongly enforced. Many political groups emerged with new ideas at this time. One of the most radical (extreme) groups was the Levellers. -

Cromwelliana 2012

CROMWELLIANA 2012 Series III No 1 Editor: Dr Maxine Forshaw CONTENTS Editor’s Note 2 Cromwell Day 2011: Oliver Cromwell – A Scottish Perspective 3 By Dr Laura A M Stewart Farmer Oliver? The Cultivation of Cromwell’s Image During 18 the Protectorate By Dr Patrick Little Oliver Cromwell and the Underground Opposition to Bishop 32 Wren of Ely By Dr Andrew Barclay From Civilian to Soldier: Recalling Cromwell in Cambridge, 44 1642 By Dr Sue L Sadler ‘Dear Robin’: The Correspondence of Oliver Cromwell and 61 Robert Hammond By Dr Miranda Malins Mrs S C Lomas: Cromwellian Editor 79 By Dr David L Smith Cromwellian Britain XXIV : Frome, Somerset 95 By Jane A Mills Book Reviews 104 By Dr Patrick Little and Prof Ivan Roots Bibliography of Books 110 By Dr Patrick Little Bibliography of Journals 111 By Prof Peter Gaunt ISBN 0-905729-24-2 EDITOR’S NOTE 2011 was the 360th anniversary of the Battle of Worcester and was marked by Laura Stewart’s address to the Association on Cromwell Day with her paper on ‘Oliver Cromwell: a Scottish Perspective’. ‘Risen from Obscurity – Cromwell’s Early Life’ was the subject of the study day in Huntingdon in October 2011 and three papers connected with the day are included here. Reflecting this subject, the cover illustration is the picture ‘Cromwell on his Farm’ by Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893), painted in 1874, and reproduced here courtesy of National Museums Liverpool. The painting can be found in the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight Village, Wirral, Cheshire. In this edition of Cromwelliana, it should be noted that the bibliography of journal articles covers the period spring 2009 to spring 2012, addressing gaps in the past couple of years. -

Remembering King Charles I: History, Art and Polemics from the Restoration to the Reform Act T

REMEMBERING KING CHARLES I: HISTORY, ART AND POLEMICS FROM THE RESTORATION TO THE REFORM ACT T. J. Allen Abstract: The term Restoration can be used simply to refer to the restored monarchy under Charles II, following the Commonwealth period. But it can also be applied to a broader programme of restoring the crown’s traditional prerogatives and rehabilitating the reign of the king’s father, Charles I. Examples of this can be seen in the placement of an equestrian statue of Charles I at Charing Cross and a related poem by Edmund Waller. But these works form elements in a process that continued for 200 years in which the memory of Charles I fused with contemporary constitutional debates. The equestrian statue of Charles I at Charing Cross, produced by the French sculptor Hubert Le Sueur c1633 and erected in 1675. Photograph: T. J. Allen At the southern end of Trafalgar Square, looking towards Whitehall, stands an equestrian statue of Charles I. This is set on a pedestal whose design has been attributed to Sir Christopher Wren and was carved by Joshua Marshall, Master Mason to Charles II. The bronze figure was originally commissioned by Richard Weston (First Earl of Portland, the king’s Lord High Treasurer) and was produced by the French sculptor Hubert Le Sueur in the early 1630s. It originally stood in 46 VIDES 2014 the grounds of Weston’s house in Surrey, but as a consequence of the Civil War was later confiscated and then hidden. The statue’s existence again came to official attention following the Restoration, when it was acquired by the crown, and in 1675 placed in its current location. -

PLEASE NOTE This Is a Draft Paper Only and Should Not Be Cited Without

PLEASE NOTE This is a draft paper only and should not be cited without the author’s express permission THE SHORT-TERM IMPACT OF THE >GLORIOUS REVOLUTION= ON THE ENGLISH JUDICIAL SYSTEM On February 14, 1689, The day after William and Mary were recognized by the Convention Parliament as King and Queen, the first members of their Privy Council were sworn in. And, during the following two to three weeks, all of the various high offices in the government and the royal household were filled. Most of the politically powerful posts went either to tories or to moderates. The tory Earl of Danby was made Lord President of the Council and another tory, the Earl of Nottingham was made Secretary of State for the Southern Department. The office of Lord Privy Seal was given to the Atrimming@ Marquess of Halifax, whom dedicated whigs had still not forgiven for his part in bringing about the disastrous defeat of the exclusion bill in the Lords= house eight years earlier. Charles Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, who was named Principal Secretary of State, can really only be described as tilting towards the whigs at this time. But, at the Admiralty and the Treasury, both of which were put into commission, in each case a whig stalwart was named as the first commissioner--Lord Mordaunt and Arthur Herbert respectivelyBand also in each case a number of other leading whigs were named to the commission as well.i Whig lawyers, on the whole, did rather better than their lay fellow-partisans. Devonshire lawyer and Inner Temple Bencher Henry Pollexfen was immediately appointed Attorney- General, and his cousin, Middle Templar George Treby, Solicitor General. -

Muhlenberg College Digital Repository

Muhlenberg College Digital Repository Tighe, William J. “Five Elizabethan Courtiers, Their Catholic Connections, and Their Careers.” British Catholic History 33.02 (2016): 211–227. NOTE: This is the peer-reviewed post-print (author’s final manuscript), identical in textual content to the publisher PDF available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british- catholic-history . Copyright 2016 Cambridge UP. The post-print has been deposited in this repository in accordance with publisher policy. Use of this publication is governed by copyright law and license agreements. COVER SHEET William J. Tighe, Ph.D. History Department Muhlenberg College 2400 Chew Street Allentown, PA 18104-5586 UNITED STATES E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: 001.1.484.664.3325 Academic affiliation: Associate Professor, History Department, Muhlenberg College ABSTRACT This article briefly surveys men and women holding positions in the Privy Chamber of Elizabeth I and men holding significant positions in the (outer) Chamber for evidence of Catholic beliefs, sympathies or family connections before going on to discuss the careers of five men who at various times in her reign were members of the Band of Gentlemen Pensioners and whose court careers were decisively affected for weal or for woe by their Catholic beliefs (or, in one case, temporary repudiation of Catholicism) or connections. The men’s careers witness both to a fluidity of religious identity which might facilitate their advancement at Court, but also to its narrowing over the course of the reign. KEY WORDS Elizabethan Catholic courtiers. Religious identity. 1 FIVE ELIZABETHAN COURTIERS, THEIR CATHOLIC CONNECTIONS, AND THEIR CAREERS This article is a preliminary investigation of the careers of known or suspected Catholics in the upper reaches of the Elizabethan Court, among those closest to the Queen in the Privy Chamber and Chamber. -

Thought, Word and Deed in the Mid-Tudor Commonwealth : Sir Thomas Smith and Sir William Cecil in the Reign of Edward VI

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1979 Thought, word and deed in the mid-Tudor Commonwealth : Sir Thomas Smith and Sir William Cecil in the reign of Edward VI Ann B. Clark Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Economic History Commons, and the European History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Clark, Ann B., "Thought, word and deed in the mid-Tudor Commonwealth : Sir Thomas Smith and Sir William Cecil in the reign of Edward VI" (1979). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2776. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2772 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. / AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Ann B. Clarke for the Master of Arts in History presented 18 May 1979. l I· Title: Thought, Word and Deed in the Mid-Tudor Commonwealth: Sir Thomas Smith:and Sir William Cecil in the Reign of Edward VI. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COlfiMITTEE: Ann Weikel, Chairman Charles LeGuin · Michael Reardon This thesis examines the general economic and intel- lectual climate of the mid-Tudor Commonwealth as a background for a specific study of the financial reforms instituted by Edward VI's government while the Duke of Northumberland controlled the Privy Council. The philosophy behind these measures parallels the principles expressed in A Discourse of the Commonweal of this Realm of England, a treatise written in 1549 by Sir Thomas Smith, Secretary to King Edward. -

Behavioural Sciences, Research Methods

ROUTLEDGE Behavioural Sciences and Research Methods Catalogue 2021 January - June New and Forthcoming Titles www.routledge.com Welcome THE EASY WAY TO ORDER Welcome to the January to June 2021 Behavioural Sciences and Book orders should be addressed to the Research Methods catalogue. Taylor & Francis Customer Services Department at Bookpoint, or the appropriate overseas offices. We welcome your feedback on our publishing programme, so please do not hesitate to get in touch – whether you want to read, write, review, adapt or buy, we want to hear from you, so please visit our website below or please contact your local sales representative for Contacts more information. UK and Rest of World: Bookpoint Ltd www.routledge.com Tel: +44 (0) 1235 400524 Email: [email protected] USA: Taylor & Francis Tel: 800-634-7064 Email: [email protected] Asia: Taylor & Francis Asia Pacific Tel: +65 6508 2888 Email: [email protected] China: Taylor & Francis China Prices are correct at time of going to press and may be subject to change without Tel: +86 10 58452881 notice. Some titles within this catalogue may not be available in your region. Email: [email protected] India: Taylor & Francis India Tel: +91 (0) 11 43155100 eBooks Partnership Opportunities at Email: [email protected] We have over 50,000 eBooks available across the Routledge Humanities, Social Sciences, Behavioural Sciences, At Routledge we always look for innovative ways to Built Environment, STM and Law, from leading support and collaborate with our readers and the Imprints, including Routledge, Focal Press and organizations they represent. Psychology Press. -

The Elizabethan Court Day by Day--1587

1587 1587 At GREENWICH PALACE, Kent. Jan 1,Sun New Year gifts. Gift Roll not extant, but Lord Lumley gave the Queen ‘A book wherein are divers Psalms in Latin written, the boards great, enclosed all over on the outside with gold enamelled cut-work, with divers colours, and one little clasp’. Works: ‘Setting up a table 40 foot long in the Privy Gallery to lay the New Year’s Gifts for her Majesty to see them...Setting up the banquet-table’. Also Jan 1: play, by the Queen’s Men.T John Pigeon, Jewel-house Officer, went to the goldsmiths for a present for ‘Monsieur Bellièvre, Ambassador from the French King’.T The French had planned to leave on December 30, but ‘when we were all ready and booted’ the Queen sent two of her gentlemen to ask them to wait another two or three days. Jan 1: Another conspiracy to murder the Queen discovered. William Harrison’s description: ‘Another conspiracy is detected upon New Year’s Day wherein the death of our Queen is once again intended by Stafford and others at the receipt of her New Year’s gifts, but as God hath taken upon him the defence of his own cause so hath he in extraordinary manner from time to time preserved her Majesty from the treason and traitorous practices of her adversaries and wonderfully betrayed their devices’. [Chronology, f.264]. The conspiracy is described in notes by Lord Burghley, February 17, as ‘a practice betwixt the French Ambassador and a lewd young miscontented person named William Stafford, and one Moody, a prisoner in Newgate, a mischievous resolute person, how her Majesty’s life should be taken away’.