The Ideology of Jury Law-Finding in the Interregnum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

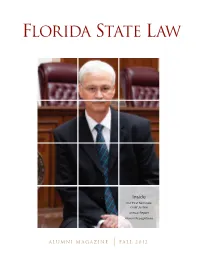

Fall 2012 Florida State Law Magazine

FLORIDA STATE LAW Inside Our First Seminole Chief Justice Annual Report Alumni Recognitions ALUMNI MAGAZINE FALL 2012 Message from the Dean Jobs, Alumni, Students and Admissions Players in the Jobs Market Admissions and Rankings This summer, the Wall Street The national press has highlighted the related phenomena Journal reported that we are the of the tight legal job market and rising student indebtedness. nation’s 25th best law school when it More prospective applicants are asking if a law degree is worth comes to placing our new graduates the cost, and law school applications are down significantly. in jobs that require law degrees. Just Ours have fallen by approximately 30% over the past two years. this month, Law School Transparency Moreover, our “yield” rate has gone down, meaning that fewer ranked us the nation’s 26th best law students are accepting our offers of admission. Our research school in terms of overall placement makes clear: prime competitor schools can offer far more score, and Florida’s best. Our web generous scholarship packages. To attract the top students, page includes more detailed information on our placement we must limit our enrollment and increase scholarship awards. outcomes. In short, we rank very high nationally in terms We are working with our university administration to limit of the number of students successfully placed. Although our our enrollment, which of course has financial implications average starting salary of $58,650 is less than those at the na- both for the law school and for the central university. It is tion’s most elite private law schools, so is our average student also imperative to increase our endowment in a way that will indebtedness, which is $73,113. -

Political Ideas and Movements That Created the Modern World

harri+b.cov 27/5/03 4:15 pm Page 1 UNDERSTANDINGPOLITICS Understanding RITTEN with the A2 component of the GCE WGovernment and Politics A level in mind, this book is a comprehensive introduction to the political ideas and movements that created the modern world. Underpinned by the work of major thinkers such as Hobbes, Locke, Marx, Mill, Weber and others, the first half of the book looks at core political concepts including the British and European political issues state and sovereignty, the nation, democracy, representation and legitimacy, freedom, equality and rights, obligation and citizenship. The role of ideology in modern politics and society is also discussed. The second half of the book addresses established ideologies such as Conservatism, Liberalism, Socialism, Marxism and Nationalism, before moving on to more recent movements such as Environmentalism and Ecologism, Fascism, and Feminism. The subject is covered in a clear, accessible style, including Understanding a number of student-friendly features, such as chapter summaries, key points to consider, definitions and tips for further sources of information. There is a definite need for a text of this kind. It will be invaluable for students of Government and Politics on introductory courses, whether they be A level candidates or undergraduates. political ideas KEVIN HARRISON IS A LECTURER IN POLITICS AND HISTORY AT MANCHESTER COLLEGE OF ARTS AND TECHNOLOGY. HE IS ALSO AN ASSOCIATE McNAUGHTON LECTURER IN SOCIAL SCIENCES WITH THE OPEN UNIVERSITY. HE HAS WRITTEN ARTICLES ON POLITICS AND HISTORY AND IS JOINT AUTHOR, WITH TONY BOYD, OF THE BRITISH CONSTITUTION: EVOLUTION OR REVOLUTION? and TONY BOYD WAS FORMERLY HEAD OF GENERAL STUDIES AT XAVERIAN VI FORM COLLEGE, MANCHESTER, WHERE HE TAUGHT POLITICS AND HISTORY. -

Reform of the Elected Judiciary in Boss Tweed’S New York

File: 3 Lerner - Corrected from Soft Proofs.doc Created on: 10/1/2007 11:25:00 PM Last Printed: 10/7/2007 6:34:00 PM 2007] 109 FROM POPULAR CONTROL TO INDEPENDENCE: REFORM OF THE ELECTED JUDICIARY IN BOSS TWEED’S NEW YORK Renée Lettow Lerner* INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................... 111 I. THE CONSTITUTION OF 1846: POPULAR CONTROL...................... 114 II. “THE THREAT OF HOPELESS BARBARISM”: PROBLEMS WITH THE NEW YORK JUDICIARY AND LEGAL SYSTEM AFTER THE CIVIL WAR .................................................. 116 A. Judicial Elections............................................................ 118 B. Abuse of Injunctive Powers............................................. 122 C. Patronage Problems: Referees and Receivers................ 123 D. Abuse of Criminal Justice ............................................... 126 III. THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION OF 1867-68: JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE............................................................. 130 A. Participation of the Bar at the Convention..................... 131 B. Natural Law Theories: The Law as an Apolitical Science ................................... 133 C. Backlash Against the Populist Constitution of 1846....... 134 D. Desire to Lengthen Judicial Tenure................................ 138 E. Ratification of the Judiciary Article................................ 143 IV. THE BAR’S REFORM EFFORTS AFTER THE CONVENTION ............ 144 A. Railroad Scandals and the Times’ Crusade.................... 144 B. Founding -

Telling the Truth About Class

TELLING THE TRUTH ABOUT CLASS G. M. TAMÁS ne of the central questions of social theory has been the relationship Obetween class and knowledge, and this has also been a crucial question in the history of socialism. Differences between people – acting and knowing subjects – may influence our view of the chances of valid cognition. If there are irreconcilable discrepancies between people’s positions, going perhaps as far as incommensurability, then unified and rational knowledge resulting from a reasoned dialogue among persons is patently impossible. The Humean notion of ‘passions’, the Nietzschean notions of ‘resentment’ and ‘genealogy’, allude to the possible influence of such an incommensurability upon our ability to discover truth. Class may be regarded as a problem either in epistemology or in the philosophy of history, but I think that this separation is unwarranted, since if we separate epistemology and the philosophy of history (which is parallel to other such separations characteristic of bourgeois society itself) we cannot possibly avoid the rigidly-posed conundrum known as relativism. In speak- ing about class (and truth, and class and truth) we are the heirs of two socialist intellectual traditions, profoundly at variance with one another, although often intertwined politically and emotionally. I hope to show that, up to a point, such fusion and confusion is inevitable. All versions of socialist endeavour can and should be classified into two principal kinds, one inaugurated by Rousseau, the other by Marx. The two have opposite visions of the social subject in need of liberation, and these visions have determined everything from rarefied epistemological posi- tions concerning language and consciousness to social and political attitudes concerning wealth, culture, equality, sexuality and much else. -

Brycheiniog Vol 42:44036 Brycheiniog 2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 1

68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 1 BRYCHEINIOG Cyfnodolyn Cymdeithas Brycheiniog The Journal of the Brecknock Society CYFROL/VOLUME XLII 2011 Golygydd/Editor BRYNACH PARRI Cyhoeddwyr/Publishers CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG A CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY AND MUSEUM FRIENDS 68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 2 CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG a CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY and MUSEUM FRIENDS SWYDDOGION/OFFICERS Llywydd/President Mr K. Jones Cadeirydd/Chairman Mr J. Gibbs Ysgrifennydd Anrhydeddus/Honorary Secretary Miss H. Gichard Aelodaeth/Membership Mrs S. Fawcett-Gandy Trysorydd/Treasurer Mr A. J. Bell Archwilydd/Auditor Mrs W. Camp Golygydd/Editor Mr Brynach Parri Golygydd Cynorthwyol/Assistant Editor Mr P. W. Jenkins Curadur Amgueddfa Brycheiniog/Curator of the Brecknock Museum Mr N. Blackamoor Pob Gohebiaeth: All Correspondence: Cymdeithas Brycheiniog, Brecknock Society, Amgueddfa Brycheiniog, Brecknock Museum, Rhodfa’r Capten, Captain’s Walk, Aberhonddu, Brecon, Powys LD3 7DS Powys LD3 7DS Ôl-rifynnau/Back numbers Mr Peter Jenkins Erthyglau a llyfrau am olygiaeth/Articles and books for review Mr Brynach Parri © Oni nodir fel arall, Cymdeithas Brycheiniog a Chyfeillion yr Amgueddfa piau hawlfraint yr erthyglau yn y rhifyn hwn © Except where otherwise noted, copyright of material published in this issue is vested in the Brecknock Society & Museum Friends 68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 3 CYNNWYS/CONTENTS Swyddogion/Officers -

English Renaissance

1 ENGLISH RENAISSANCE Unit Structure: 1.0 Objectives 1.1 The Historical Overview 1.2 The Elizabethan and Jacobean Ages 1.2.1 Political Peace and Stability 1.2.2 Social Development 1.2.3 Religious Tolerance 1.2.4 Sense and Feeling of Patriotism 1.2.5 Discovery, Exploration and Expansion 1.2.6 Influence of Foreign Fashions 1.2.7 Contradictions and Set of Oppositions 1.3 The Literary Tendencies of the Age 1.3.1 Foreign Influences 1.3.2 Influence of Reformation 1.3.3 Ardent Spirit of Adventure 1.3.4 Abundance of Output 1.4 Elizabethan Poetry 1.4.1 Love Poetry 1.4.2 Patriotic Poetry 1.4.3 Philosophical Poetry 1.4.4 Satirical Poetry 1.4.5 Poets of the Age 1.4.6 Songs and Lyrics in Elizabethan Poetry 1.4.7 Elizabethan Sonnets and Sonneteers 1.5 Elizabethan Prose 1.5.1 Prose in Early Renaissance 1.5.2 The Essay 1.5.3 Character Writers 1.5.4 Religious Prose 1.5.5 Prose Romances 2 1.6 Elizabethan Drama 1.6.1 The University Wits 1.6.2 Dramatic Activity of Shakespeare 1.6.3 Other Playwrights 1.7. Let‘s Sum up 1.8 Important Questions 1.0. OBJECTIVES This unit will make the students aware with: The historical and socio-political knowledge of Elizabethan and Jacobean Ages. Features of the ages. Literary tendencies, literary contributions to the different of genres like poetry, prose and drama. The important writers are introduced with their major works. With this knowledge the students will be able to locate the particular works in the tradition of literature, and again they will study the prescribed texts in the historical background. -

POLITICS, SOCIETY and CIVIL WAR in WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History

Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History Series editors ANTHONY FLETCHER Professor of History, University of Durham JOHN GUY Reader in British History, University of Bristol and JOHN MORRILL Lecturer in History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow and Tutor of Selwyn College This is a new series of monographs and studies covering many aspects of the history of the British Isles between the late fifteenth century and the early eighteenth century. It will include the work of established scholars and pioneering work by a new generation of scholars. It will include both reviews and revisions of major topics and books which open up new historical terrain or which reveal startling new perspectives on familiar subjects. It is envisaged that all the volumes will set detailed research into broader perspectives and the books are intended for the use of students as well as of their teachers. Titles in the series The Common Peace: Participation and the Criminal Law in Seventeenth-Century England CYNTHIA B. HERRUP Politics, Society and Civil War in Warwickshire, 1620—1660 ANN HUGHES London Crowds in the Reign of Charles II: Propaganda and Politics from the Restoration to the Exclusion Crisis TIM HARRIS Criticism and Compliment: The Politics of Literature in the Reign of Charles I KEVIN SHARPE Central Government and the Localities: Hampshire 1649-1689 ANDREW COLEBY POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, i620-1660 ANN HUGHES Lecturer in History, University of Manchester The right of the University of Cambridge to print and sell all manner of books was granted by Henry VIII in 1534. -

"This Court Doth Keep All England in Quiet": Star Chamber and Public Expression in Prerevolutionary England, 1625–1641 Nathaniel A

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2018 "This Court Doth Keep All England in Quiet": Star Chamber and Public Expression in Prerevolutionary England, 1625–1641 Nathaniel A. Earle Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Earle, Nathaniel A., ""This Court Doth Keep All England in Quiet": Star Chamber and Public Expression in Prerevolutionary England, 1625–1641" (2018). All Theses. 2950. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2950 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "THIS COURT DOTH KEEP ALL ENGLAND IN QUIET" STAR CHAMBER AND PUBLIC EXPRESSION IN PREREVOLUTIONARY ENGLAND 1625–1641 A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts History by Nathaniel A. Earle August 2018 Accepted by: Dr. Caroline Dunn, Committee Chair Dr. Alan Grubb Dr. Lee Morrissey ABSTRACT The abrupt legislative destruction of the Court of Star Chamber in the summer of 1641 is generally understood as a reaction against the perceived abuses of prerogative government during the decade of Charles I’s personal rule. The conception of the court as an ‘extra-legal’ tribunal (or as a legitimate court that had exceeded its jurisdictional mandate) emerges from the constitutional debate about the limits of executive authority that played out over in Parliament, in the press, in the pulpit, in the courts, and on the battlefields of seventeenth-century England. -

Why Did Britain Become a Republic? > New Government

Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Why did Britain become a republic? Case study 2: New government Even today many people are not aware that Britain was ever a republic. After Charles I was put to death in 1649, a monarch no longer led the country. Instead people dreamed up ideas and made plans for a different form of government. Find out more from these documents about what happened next. Report on the An account of the Poem on the arrest of setting up of the new situation in Levellers, 1649 Commonwealth England, 1649 Portrait & symbols of Cromwell at the The setting up of Cromwell & the Battle of the Instrument Commonwealth Worcester, 1651 of Government http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Page 1 Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Case study 2: New government - Source 1 A report on the arrest of some Levellers, 29 March 1649 (Catalogue ref: SP 25/62, pp.134-5) What is this source? This is a report from a committee of MPs to Parliament. It explains their actions against the leaders of the Levellers. One of the men they arrested was John Lilburne, a key figure in the Leveller movement. What’s the background to this source? Before the war of the 1640s it was difficult and dangerous to come up with new ideas and try to publish them. However, during the Civil War censorship was not strongly enforced. Many political groups emerged with new ideas at this time. One of the most radical (extreme) groups was the Levellers. -

Speakers of the House of Commons

Parliamentary Information List BRIEFING PAPER 04637a 21 August 2015 Speakers of the House of Commons Speaker Date Constituency Notes Peter de Montfort 1258 − William Trussell 1327 − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Styled 'Procurator' Henry Beaumont 1332 (Mar) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Sir Geoffrey Le Scrope 1332 (Sep) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Probably Chief Justice. William Trussell 1340 − William Trussell 1343 − Appeared for the Commons alone. William de Thorpe 1347-1348 − Probably Chief Justice. Baron of the Exchequer, 1352. William de Shareshull 1351-1352 − Probably Chief Justice. Sir Henry Green 1361-1363¹ − Doubtful if he acted as Speaker. All of the above were Presiding Officers rather than Speakers Sir Peter de la Mare 1376 − Sir Thomas Hungerford 1377 (Jan-Mar) Wiltshire The first to be designated Speaker. Sir Peter de la Mare 1377 (Oct-Nov) Herefordshire Sir James Pickering 1378 (Oct-Nov) Westmorland Sir John Guildesborough 1380 Essex Sir Richard Waldegrave 1381-1382 Suffolk Sir James Pickering 1383-1390 Yorkshire During these years the records are defective and this Speaker's service might not have been unbroken. Sir John Bussy 1394-1398 Lincolnshire Beheaded 1399 Sir John Cheyne 1399 (Oct) Gloucestershire Resigned after only two days in office. John Dorewood 1399 (Oct-Nov) Essex Possibly the first lawyer to become Speaker. Sir Arnold Savage 1401(Jan-Mar) Kent Sir Henry Redford 1402 (Oct-Nov) Lincolnshire Sir Arnold Savage 1404 (Jan-Apr) Kent Sir William Sturmy 1404 (Oct-Nov) Devonshire Or Esturmy Sir John Tiptoft 1406 Huntingdonshire Created Baron Tiptoft, 1426. -

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform The Library of Sir Geoffrey Bindman, QC. Part I. BERNARD QUARITCH LTD MMXX BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 36 Bedford Row, London, WC1R 4JH tel.: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 email: [email protected] / [email protected] web: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC 1 Churchill Place London E14 5HP Sort code: 20-65-90 Account number: 10511722 Swift code: BUKBGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB71 BUKB 2065 9010 5117 22 Euro account: IBAN: GB03 BUKB 2065 9045 4470 11 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB19 BUKB 2065 9063 9924 44 VAT number: GB 322 4543 31 Front cover: from item 106 (Gillray) Rear cover: from item 281 (Peterloo Massacre) Opposite: from item 276 (‘Martial’) List 2020/1 Introduction My father qualified in medicine at Durham University in 1926 and practised in Gateshead on Tyne for the next 43 years – excluding 6 years absence on war service from 1939 to 1945. From his student days he had been an avid book collector. He formed relationships with antiquarian booksellers throughout the north of England. His interests were eclectic but focused on English literature of the 17th and 18th centuries. Several of my father’s books have survived in the present collection. During childhood I paid little attention to his books but in later years I too became a collector. During the war I was evacuated to the Lake District and my school in Keswick incorporated Greta Hall, where Coleridge lived with Robert Southey and his family. So from an early age the Lake Poets were a significant part of my life and a focus of my book collecting. -

C:\Users\User1\Documents

Date:June 3,2021 Last Web Update:September 2,2020 WHITLOCK FAMILY RESEARCH - PRINTED & ORIGINAL SOURCES R0001/20 Research by Wilfred John Whitlock - Whitlocks of Langtree, Devon to 1968 R0002/7 Whitlocks of Devon research by J.R. Powell Nov.1910 R0002A/5 Whitlocks of Warkleigh, Langtree, Parkham, Devon from Kate Johnson (nee Whitlock) June 1968 R0003/6 Photocopies of Whitelocke entries in Biographical Dictionary R0004/1 Whitlocks of Warkleigh with connection to Whitlocks of Illinois by Frank M. Whitlock 1936 R0004A/1 Whitlocks of Warkleigh descent from John Lake of Bradmore (Bodleian Library:Rawl D 287) R0004B/1 Whitlocks of Warkleigh descent from John Lake from Visitation of Devon (edit J.L. Vivian. Exeter 1895) R0005/4 Letter from M.M. Johns to Elmo Ashton re Whitlocks of Langtree, Devon R0006/2 Biography of Brand Whitlock (1869-1934) R0007/3 Whitlocks of Devon parish register extracts R0008/1 Biography of Percy Whitlock (1903-1946) from Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians from M.M. Johns R0009/1 Letter Dd. June 7,1906 from J. Stanley Wedlock of Stanley Bridge, P.E.I.. to John Whitlock of Holdsworthy (sic), Devon R0010/3 Whitlock extracts from Biographical Dictionaries from J.E.I. Wyatt R0011/2 Alumni Oxonienses, The Members of the University of Oxford, 1500-1714 by Joseph Foster from Ruth Spalding R0012/1 Biographical sketch of Thomas Whitlock (1806-1875)'s life by Rev.W.C.Beer R0013/54 Whitlocks of Berkshire descent from John Whitlock & Agnes De la Beche (M about 1454) from J. Wyatt 1969 R0014/ (renumbered) R0015/1 Newspaper clipping re 50th Wedding Anniversary of Mr.