Camp Fremont and WWI Stanford’S Creative Writing Program in This Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palo Alto Activity Guide

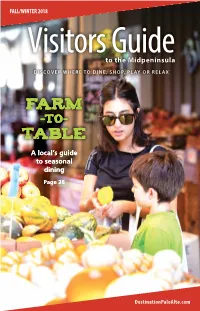

FALL/WINTER 2018 Visitors Guide to the Midpeninsula DISCOVER WHERE TO DINE, SHOP, PLAY OR RELAX Fa r m -to- table A local’s guide to seasonal dining Page 26 DestinationPaloAlto.com TOO MAJOR TOO MINOR JUST RIGHT FOR HOME FOR HOSPITAL FOR STANFORD EXPRESS CARE When an injury or illness needs quick Express Care is attention but not in the Emergency available at two convenient locations: Department, call Stanford Express Care. Stanford Express Care Staffed by doctors, nurses, and physician Palo Alto assistants, Express Care treats children Hoover Pavilion (6+ months) and adults for: 211 Quarry Road, Suite 102 Palo Alto, CA 94304 • Respiratory illnesses • UTIs (urinary tract tel: 650.736.5211 infections) • Cold and flu Stanford Express Care • Stomach pain • Pregnancy tests San Jose River View Apartment Homes • Fever and headache • Flu shots 52 Skytop Street, Suite 10 • Back pain • Throat cultures San Jose, CA 95134 • Cuts and sprains tel: 669.294.8888 Open Everyday Express Care accepts most insurance and is by Appointment Only billed as a primary care, not emergency care, 9:00am–9:00pm appointment. Providing same-day fixes every day, 9:00am to 9:00pm. Spend the evening at THE VOICE Best of MOUNTAIN VIEW 2018 THE THE VOICE Best of VOICE Best of MOUNTAIN MOUNTAIN VIEW VIEW 2016 2017 Castro Street’s Best French and Italian Food 650.968.2300 186 Castro Street, www.lafontainerestaurant.com Mountain View Welcome The Midpeninsula offers something for everyone hether you are visiting for business or pleasure, or W to attend a conference or other event at Stanford University, you will quickly discover the unusual blend of intellect, innovation, culture and natural beauty that makes up Palo Alto and the rest of the Midpeninsula. -

Ftitdw~ Flu PUBLISHED DAILY Ander Order of the PIREJZDENT of the UNITED STATES by COMMITTEE an PUBLIC INFORMATION GEORGE CREEL, Chairman * * * COMPLETE Record of U

(1)ftitdW~ flu PUBLISHED DAILY ander order of THE PIREJZDENT of THE UNITED STATES by COMMITTEE an PUBLIC INFORMATION GEORGE CREEL, Chairman * * * COMPLETE Record of U. S. GOVERNMENT Activities VOL. 2 WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, JULY 19, 1918. No. 364 CONTRACTS FOR 61 VESSELS U. S. TROOPS ADVANCE U.S. S. WESTOVER SUNK OF 439,800 DEAD-WEIGHT TONS IN COUNTER ATTACK BY TORPEDO ON JULY 11 LET BY THE SHIPPING BOARD WITH GREATEST DASH INEUROPEAN WATERS; 47 TO BE OF STEEL CONSTRUCTION The Secretary of War made the following statement to the TEN OF CREW MISSING Skinner and Eddy Corporation of press yesterday afternoon: WAS A SUPPLY VESSEL Seattle to Build Thirty-Five of The department has received from Gen. Pershing an official the Ships-Fourteen, of 47,000 confirmation of the opening of Ship Was Eastbound When Tons, to be Wooden Vessels. the counteroffensive along the Sunk-Eighty-Two qf the lines carried in the newspaper Crew Rescued-Assistant dispatches. American troops are The Shipping Board authorizes the fol- Paymaster R. H. Halstead Jowing: participating both as complete During the week ending July 18 con- divisions and as units in associa- and Ensign R. D. Caldwell tion with the French. The first tracts for 61 vessels, representing 439,800 -Among Those Missing. dead-weight tons, were let by the United objectives seem everywhere to have been attained, and while States Shipping Board and Emergency The Navy Department authorizes the Fleet Corporation. Of this tonnage 392,- no accurate count has been made it is clear that many prisoners following: 800 will go into steel construction, the The Navy Department is informed rest into wooden ships. -

Washington National Guard Pamphlet

WASH ARNG PAM 870-1-5 WASH ANG PAM 210-1-5 WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD PAMPHLET THE OFFICIAL HISTORY OF THE WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD VOLUME 5 WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD IN WORLD WAR I HEADQUARTERS MILITARY DEPARTMENT STATE OF WASHINGTON OFFICE OF THE ADJUTANT GENERAL CAMP MURRAY, TACOMA 33, WASHINGTON THIS VOLUME IS A TRUE COPY THE ORIGINAL DOCUMENT ROSTERS HEREIN HAVE BEEN REVISED BUT ONLY TO PUT EACH UNIT, IF POSSIBLE, WHOLLY ON A SINGLE PAGE AND TO ALPHABETIZE THE PERSONNEL THEREIN DIGITIZED VERSION CREATED BY WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME 5 WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD IN WORLD WAR I. CHAPTER PAGE I WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD IN THE POST ..................................... 1 PHILIPPINE INSURRECTION PERIOD II WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD MANEUVERS ................................. 21 WITH REGULAR ARMY 1904-12 III BEGINNING OF THE COAST ARTILLERY IN ........................................... 34 THE WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD IV THE NAVAL MILITIA OF THE WASHINGTON .......................................... 61 NATIONAL GUARD V WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD IN THE ............................................. 79 MEXICAN BORDER INCIDENT VI WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD IN THE ........................................... 104 PRE - WORLD WAR I PERIOD VII WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD IN WORLD WAR I .......................114 - i - - ii - CHAPTER I WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD IN THE POST PHILIPPINE INSURRECTION PERIOD It may be recalled from the previous chapter that with the discharge of members of the Washington National Guard to join the First Regiment of United States Volunteers and the federalizing of the Independent Washington Battalion, the State was left with no organized forces. Accordingly, Governor Rogers, on 22 July 1898, directed Adjutant General William J. Canton to re-establish a State force in Conformity with the Military Code of Washington. -

Community Development

AGENDA ITEM L1 Community Development STAFF REPORT City Council Meeting Date: 4/17/2018 Staff Report Number: 18-073-CC Informational Item: Update on 241 El Camino Real (The Oasis) and 201- 211 El Camino Real/610 Cambridge Ave. Recommendation This is an informational item and does not require City Council action. Policy Issues Mayor Pro Tem Ray Mueller has asked for a status update on the subject property, where The Oasis restaurant and lounge ceased operations as of March 7, 2018. Specifically inquiring if the existing building is eligible for historic designation for the National Register of Historic Places and the California Register of Historical Resources. Additional information has been requested for a proposed mixed-use development at an adjacent property located at 201-211 El Camino Real/610 Cambridge Ave. Background The subject building has been evaluated as being eligible for both the federal and California Historic Registers. A 1990 historic resources inventory and a 2013 Historic Resource Evaluation (HRE) confirmed the building’s historic eligibility. As a result, any exterior alterations/additions would need to be conducted in compliance with the secretary of the interior’s standards for rehabilitation, as evaluated by a qualified architectural historian. Demolition of the building would likely not be permitted without an environmental impact report (EIR) and associated statement of overriding considerations. In 2001, the Planning Commission granted a use permit and architectural control for new wireless equipment, specifically new cell antennas within an enclosure were added to the building’s roof. In 2012- 2013, Sprint applied for a use permit revision to replace the previously-installed antennas with new enclosed roof-mounted antennas. -

WWI Serviceman Glossary

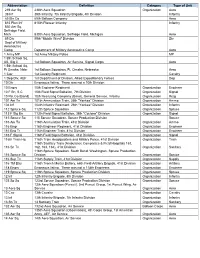

Abbreviation Definition Category Type of Unit 239 Aer Sq 238th Aero Squadron Organization Aero 39 Inf 39th Infantry, 7th Infantry Brigade, 4th Division Infantry 65 Bln Co 65th Balloon Company Aero 815 Pion Inf 815th Pioneer Infantry Infantry 830 Aer Sq, Selfridge Field, Mich 830th Aero Squadron, Selfridge Field, Michigan Aero 89 Div 89th "Middle West" Division Div Dept of Military Aeronautics Camp Department of Military Aeronautics Camp Aero 1 Army MP 1st Army Military Police MP 1 Bln School Sq, AS, Sig C 1st Balloon Squadron, Air Service, Signal Corps Aero 1 Bln School Sq, Ft Omaha, Nebr 1st Balloon Squadron, Ft. Omaha, Nebraska Aero 1 Cav 1st Cavalry Regiment Cavalry 1 Dep Div, AEF 1st Department of Division, Allied Expeditionary Forces Dep 10 Div Erroneous listing. There was not a 10th Division 10 Engrs 10th Engineer Regiment Organization Engineer 10 F Bn, S C 10th Field Signal Battalion, 7th Division Organization Signal 10 Rct Co (Band) 10th Recruiting Company (Band), General Service, Infantry Organization Rctg 101 Am Tn 101th Ammunition Train, 26th "Yankee" Division Organization Ammo 104 Inf 104th Infantry Regiment, 26th "Yankee" Division Organization Infantry 112 Spruce Sq 112th Spruce Squadron Organization Spruce 113 F Sig Bn 113th Field Signal Battalion, 38th "Cyclone" Division Organization Signal 115 Spruce Sq 115 Spruce Squadron, Spruce Production Division Spruce 116 Am Tn 116th Ammunition Train, 41st Division Organization Ammo 116 Engr 116th Engineer Regiment, 41st Division Organization Engineer 116 Eng Tr 116th Engineer Train, -

Fall Saturday Morning Historic Walking Tours New Stops! New Leaders! Best of All, There Are No Conflicts with Football Games

PAST News Vol. 30, No. 2 P.O. Box 308 • Palo Alto, California 94302 Summer 2018 Fall Saturday Morning Historic Walking Tours New stops! New leaders! Best of all, there are no conflicts with football games. (Stanford’s schedule is full of night football.) Tours are free, although donations are always welcome! Join us for a fun and friendly walk through town — We look forward to seeing you. College Terrace Led by Carolyn George Oct. 6 Meet at 1181 College (corner of College and Harvard) Downtown Led by Margaret Feuer and Bo Crane Oct. 13 Meet at City Hall Plaza, 250 Hamilton Avenue (See page 5 for a tidbit from this tour) Professorville Led by Bo Crane and Anne Gregor Oct. 20 Meet at 1005 Bryant (corner of Bryant and Addison) Homer Avenue Led by Steve Emslie Nov. 2 Meet at The Woman’s Club, 475 Homer Avenue Rain or shine! – All tours start at 10 a.m. Thirty years after PAST’s beginning when planning for the 1988 CPF Conference, we were honored to contribute $5,000 to be a Capital Sponsor of the 2018 conference when it returned to Palo Alto-Stanford in May. Our participation included an information table at the headquarters, leading two tours, Downtown and Professorville, a Homer Avenue seminar, and providing the speaker for the kickoff reception. (See page 6 for excerpts from Barbara Wilcox’s talk.) The conference theme was Deep Roots in Dynamic Times. President’s Letter want to thank you for your support of While the price of solar panels has be- PAST Heritage during 2018. -

Yosemite Nature Notes

Yosemite Nature Notes Ex. ma JULY, 1951 IaiA: 7 Flynt() I . The Camp Fremont Treaty, Mariposa Creek, March 19, 1851 (Chart hared on mat s " California I, " IHtlr Aauunl Report Iiurrnu American Iitirn,rlortV, Parl 2, 1899). This treaty was signed on the some day that the Mariposa Battalion set out upon the exped: Lion which resulted in the discovery of Yosemite Valley . By its terms six tribes gave up land: which extended from the coast eastward to the crest of the Sierra (No. 274 of chart). In Ili, region of the present Yosemite National Park the Merced drainage basin constituted the souther limits of the ceded lands and the Tuolumne River system formed the northern boundary . 1.. " reservation" to be occupied by these tribes was designated on lands north and northee: of the present city of Merced which included the sites of the present towns of Snelling an Merced Falls (No . 273 of chart) . George Belt, as Belt and Company, obtained exclusive rights i trade with the tribes involved in this treaty . Two of the tribes or bands, the Si-yan-te and lh ' Po-to-yan-ti, established their rancheria in the vicinity of Belt 's place of business near th ' present-day Merced Falls . The others, the Co-co-noon, A-pang-as-se, Ap-la-che, and A-wal-a-che set themselves up on the Tuolumne River at a locality above Dickerson's Ferry where a secon: Belt and Co . store was operated by William J. Howard, a partner in the company . One of ihi few literary treasures which stem from the brief trading post era in California history is Id' book, Sam Ward in the Gold Rush, Stanford University Press, 1949 . -

World War I: Two Soldiers Write Home Our Vision Table of Contents to Discover the Past and Imagine the Future

Winter 2017-2018 LaThe Journal of the SanPeninsula Mateo County Historical Association, Volume xlv, No. 2 World War I: Two Soldiers Write Home Our Vision Table of Contents To discover the past and imagine the future. With Love to All, Iler: Letters from a Camp Fremont Soldier ............................. 3 by Iler Owen Watson Our Mission Sketches from World War I: A Burlingame Soldier’s Experience ...................... 13 To inspire wonder and by Alvin Page Colby discovery of the cultural and natural history of San Mateo County. Accredited By the American Alliance of Museums. The San Mateo County Historical Association Board of Directors Barbara Pierce, Chairwoman; Mark Jamison, Vice Chairman; John Blake, Secretary; Christine Williams, Treasurer; Jennifer Acheson; Thomas Ames; Alpio Barbara; Keith Bautista; Sandra McLellan Behling; Elaine Breeze; Chonita E. Cleary; Tracy De Leuw; The San Mateo County Shawn DeLuna; Dee Eva; Ted Everett; Greg Galli; Tania Gaspar; Peggy Bort Jones; Historical Association John LaTorra; Emmet W. MacCorkle; Olivia Garcia Martinez; Rick Mayerson; Karen S. McCown; Gene Mullin; Mike Paioni; John Shroyer; Bill Stronck; Ellen Ulrich; Joseph operates the San Mateo Welch III; Darlynne Wood and Mitchell P. Postel, President. County History Museum and Archives at the old San President’s Advisory Board Mateo County Courthouse Albert A. Acena; Arthur H. Bredenbeck; David Canepa; John Clinton; T. Jack Foster, located in Redwood City, Jr.; Umang Gupta; Douglas Keyston; Greg Munks; Phill Raiser; Patrick Ryan; Cynthia L. California, and administers Schreurs and John Schrup. two county historical sites, Leadership Council the Sanchez Adobe in Arjun Gupta, Arjun Gupta Community Foundation; Paul Barulich, Barulich Dugoni Law Pacifica and the Woodside Group Inc; Tracey De Leuw, DPR Construction; Jenny Johnson, Franklin Templeton Store in Woodside. -

SERVICE RECORD ~ United States Army, Navy and Marines J

SERVICE RECORD ~ United States Army, Navy and Marines J Pullman, Washington ·'.. ' January, 1920 ( \ ) ' A record of the alumni, former students and faculty of the State College of Wash ington, who were in the military service of the Allied Countries, during the war with the Central Powers. ' ' Every effort has been made to locate per sons whose names should appear in this book. O n account of uncertain addresses, :cs mistakes are bound to occur and omissions be made. One copy of this record, with corrections, will be kept on file with the ... college librarian, and will serve as a history of the State College men in the war. Cor rections should be sent to the Librarian. ., 'I WILLIAM H. AM:os, Engineers, son of PERCY DOSH, Infantry, son of Mr. and Mr. and Mrs. A. J. Amos. Received Mrs. Charles Dosh of Palouse, Wash. training Washington Barracl-:s·, Wash Entered service October, 1918. Received ington, D. C. Died from influenza in training in S. A . T. C., State College of New York City in l\iovember, 1 918. Washington, Pullman, Wash. Died from influenza at Pullman, Wash., November, RICHARD BURBANK, Infantry, son of Mr. 1918. and Mrs. D. b. Burbank of Edmonds, Wash. E ntered service October, 1918. CARL C. DUNHAM (Pvt.); 28th Infantry, son of Mr. and Mrs. S. Dunham of Received training in S. A. T. C., State vV . Adna, Wash. Received training at College of Washington, Pullman, Wasl1. Ca mp Mills, N. Y ., and in France. Killed Died from influenza at .l:'ullman, Wash., in action on Ju1y 23 , 1918. -

653 Soldiers, Sailors and Marines Cvancara

653 Soldiers, Sailors and Marines Cvancara CVANCARA, JOSEPH G. Army number 2,560,220; registrant, Moun.- trail county; born, Prague, Bohemia, Nov. 14, 1896; naturalized citizen; occupation, farmer; inducted at Stanley on March 29, 1918; sent to Camp Dodge, Iowa; served in 163rd Depot Brigade, to April 19, 1918; Medical Department, to discharge. Discharged at Fort Des Moines, Iowa, on Oct. 21, 1919, as a Private. CYRUS, CURTIS. WILLARD. Army number 559,223•, registrant, Ward county; born, Howard Lake, Minn., May 11, 1896, of American parents; occupation, farmer; enlisted at Minot, on March 1, 1918; sent to Camp Greene, N. C.; served in Company G, 58th Infantry, to discharge. Grade: Private 1st Class, June 8, 1918; overseas from May 7, 1918, to Jan. 1, 1919; wounded, severely„ July 18, 1918. Engagement: Offensive: Aisne-Marne. Discharged at Camp Dodge, Iowa, on Feb. 3, 1919, as a Private 1st Class. CYRUS, JOSEPH ADOLPH. Army number 4,036,121; registrant, Steele county; born, Hope, N. Dak., Oct. 4, 1893, of German parents; occupation, farmer; inducted at Sherbrooke on July 22, 1918; sent to Camp Custer, Mich.; served in 160th Depot Brigade to Aug. 18, 1918; Headquarters Com- pany, 41st Field Artillery, to discharge. Grade: Corporal, Sept. 16, 1918. Discharged at Camp Dodge, Iowa, on Feb. 7, 1919, as a Corporal. CYSEWSKI, ANDREW BEN. Army number 3,083,119; not a registrant; born, Jamestown, N. Dak., April 2, 1900, of Polish parents; occupation., auto mechanic; enlisted at Minot on June 18, 1918; sent to Jefferson Bar- racks, Mo.; served in Medical Department, to discharge; overseas from Aug. -

Eighty Third Field Artillery Battalion Ralph O

Bangor Public Library Bangor Community: Digital Commons@bpl World War Regimental Histories World War Collections 1946 Eighty Third Field Artillery Battalion Ralph O. Bates Follow this and additional works at: http://digicom.bpl.lib.me.us/ww_reg_his Recommended Citation Bates, Ralph O., "Eighty Third Field Artillery Battalion" (1946). World War Regimental Histories. 23. http://digicom.bpl.lib.me.us/ww_reg_his/23 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the World War Collections at Bangor Community: Digital Commons@bpl. It has been accepted for inclusion in World War Regimental Histories by an authorized administrator of Bangor Community: Digital Commons@bpl. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "NORT ENGLAND o Wor(~t~t~~.r "'B~r11.vth </ , ~t\h.Q..It'r\ /' oH11.1d~llxwq ____ / o. ~urnbu1-o A~b~ ~ '~ Wt.IZ<I.I'\bc_"!i ITALY ..... : . ! ........ .. .,. ~. .... ... .. - ' ..... ~ .. ; "' .. ... ... -............ ." March 18th 1920 From: The ~djutant General of the Army To: The Quartermaster General, Director of Purchase and Storage Subject: Coat of Arms for the 83rd Field Artillery 1. The Secretary of War approves the following Coat-of-arms for this regiment. Party per cheveron or and gules, a cheveronal azure between in the sinister chief a Cheyenne War Benet and in base a grizzly bear passant both proper. On a cantoon tinne'a dragoon passant of the first (tor the lst Cavalry) ' CREST: On a wreath of the colors a bison statant argent. MoUo: Flagranto Bello. (Glorious in Battle) DESCRIPTION: (a) The 83rd Field Artillery was organized from the 1st Cavalry in 1917, at Fort D. -

Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919 City Health Officer Dr

Summer 2020 LaThe Journal of the SanPeninsula Mateo County Historical Association, Volume xlviii, No. 1 The Influenza Epidemic in San Mateo County Our Vision Table of Contents To discover the past and imagine the future. The Influenza Epidemic in San Mateo County (1918-1919) .............................. 3 by Mitchell P. Postel Our Mission To educate and to inspire wonder and discovery of the cultural and natural history of San Mateo County. The San Mateo County Historical Association Board of Directors Chonita E. Cleary, Chairwoman; John LaTorra, Vice Chairman; Mark Jamison, Immediate Accredited Past Chairman; John Blake, Secretary; Christine Williams, Treasurer; Jennifer Acheson; By the American Alliance Thomas Ames; Alpio Barbara; Keith Bautista; Sandra McLellan Behling; Carlos Bolanos; Russ Castle; Donna Colson; Tracy De Leuw; Shawn DeLuna; Dee Eva; Greg Galli; Wally of Museums. Jansen; Olivia Garcia Martinez; Rick Mayerson; Karen S. McCown; Gene Mullin; Bill Nicolet; Laura Peterhans; Barbara Pierce; John Shroyer; Richard Shu; Joseph Welch III and Mitchell P. Postel, President. The San Mateo County President’s Advisory Board Historical Association Paul Barulich; Arthur H. Bredenbeck; David Canepa; John Clinton; T. Jack Foster, Jr.; operates the San Mateo Umang Gupta; Douglas Keyston; Mike Paioni; Patrick Ryan and Cynthia L. Schreurs. County History Museum and Archives at the old San Leadership Council Mateo County Courthouse Paul Barulich, Barulich Dugoni & Suttmann Law Group, Inc.; Joe Cotchett, Cotchett, Pitre & McCarthy LLP; Tracy De Leuw, DPR Construction; Robert Dressler, Wells Fargo located in Redwood City, Bank; Bob Gordon, Cypress Lawn Heritage Foundation and Jenny Johnson, Franklin California, and administers Templeton. two county historical sites, the Sanchez Adobe in Pacifica and the Woodside La Peninsula Store in Woodside.