German Prisoners of War in Michigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise and Fall of Hitler's Germany

In collaboration with The National WWII Museum Travel & featuring award-winning author Alexandra Richie, DPhil PHOTO: RUSSIAN SOLDIERS LOOKING AT A TORN DOWN GERMAN NAZI EAGLE WITH SWASTIKA EMBLEM WITH SWASTIKA GERMAN NAZI EAGLE DOWN A TORN AT RUSSIAN SOLDIERS LOOKING PHOTO: OF BERLIN—1945, BERLIN, GERMANY. AFTER THE FALL IN THE RUINS OF REICH CHANCELLERY LYING The Rise and Fall of Hitler’s Germany MAY 25 – JUNE 5, 2020 A journey that takes you from Berlin to Auschwitz to Warsaw, focused on the devastating legacy of the Holocaust, the bombing raids, and the last battles. Save $1,000 per couple when booked by December 6, 2019 Howdy, Ags! In the 1930’s, the journey to World War II began in the private meeting rooms in Berlin and raucous public stadiums across Germany where the Nazis concocted and then promoted their designs for a new world order, one founded on conquest for land and racial-purity ideals. As they launched the war in Europe by invading Poland on September 1, 1939, Hitler and his followers unleashed a hell that would return to its birthplace in Berlin fewer than six years later. The Traveling Aggies are honored to partner with The National WWII Museum on a unique and poignant travel program, The Rise and Fall of Hitler’s Germany. This emotional journey will be led by WWII scholar and author Dr. Alexandra Richie, an expert on the Eastern Front and the Holocaust. Guests will travel through Germany and Poland, exploring historical sites and reflecting on how it was possible for the Nazis to rise to power and consequently bring destruction and misery across Europe. -

The Daily Egyptian, September 13, 1985

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC September 1985 Daily Egyptian 1985 9-13-1985 The aiD ly Egyptian, September 13, 1985 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_September1985 Volume 71, Issue 20 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, September 13, 1985." (Sep 1985). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1985 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in September 1985 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KGB defector reveals spy network Gus Bode LONDON CUPI ) - The chief diplomats, officials and Danish intelligence. dievski's defection, Haosp.n of the Soviet KGB spy journalists, who were given " I would say that he has said. " It has been very im operation in London has three weeks to leave the been the West's most im- portant for our common defected to the West , un country. 0rtant source of in security to have this in masking at least 25 Soviet f,ormation," Hansen said in a formation." he said. ffQ agents, the government an· WITHIN HOURS of the television Interview. •'There nounced Thursday. Denmark announcement, Danish Justice has been a close connection said the defector was a long Minister Erik Nigg Hansen hetween Gordievski and the Gordievski served in various time Western double agent. said in Copenhagen tha t Danish intelligence 'for a long diplomat.ic posts in The defection of Oleg Gor Gordievski. who served 10 time. He has given us a wealth Copenhagen from 1966 to 1970, ~ 46, dievski, and the exposure of years as a Soviet diploma t in of information." and again from 1972 to 1978, Qu. -

Episode 711, Story 1: Stalag 17 Portrait Eduardo

Episode 711, Story 1: Stalag 17 Portrait Eduardo: Our first story looks at a portrait made by an American POW in a World War Two German prison camp. 1943, as American air attacks against Germany increase; the Nazis move the growing number of captured American airmen into prisoner of war camps, called Stalags. Over 4,000 airmen ended up in Stalag 17-b, just outside of Krems, Austria, in barracks made for 240 men. How did these men survive the deprivation and hardships of one of the most infamous prisoner of war camps of the Nazi regime? 65 years after her father George Silva became a prisoner of war, Gloria Mack of Tempe, Arizona has this portrait of him drawn by another POW while they were both prisoners in Stalag 17-b. Gloria: I thought what a beautiful thing to come out of the middle of a prison camp. Eduardo: Hi, I’m Eduardo Pagan from History Detectives. Gloria: Oh, it’s nice to meet you. Eduardo: It’s nice to meet you, too! Gloria: Come on in. Eduardo: Thank you. I’M curious to see Gloria’s sketch, and hear her father’s story. It’s a beautiful portrait. When was this portrait drawn? Gloria: It was drawn in 1944. 1 Eduardo: How did you learn about this story of how he got this portrait? Gloria: Because of this little story on the back. It says, “Print from an original portrait done in May of 1944 by Gil Rhoden. We were POW’s in Stalag 17 at Krems, Austria. -

Texas POW Camp Hearne, Texas

Episode 2, 2005: Texas POW Camp Hearne, Texas Gwen: Our final story explores a forgotten piece of World War II history that unfolds on a mysterious plot of land deep in the heart of Texas. It’s summer, 1942, and Hitler’s armies are experiencing some of their first defeats, in North Africa. War offi- cials in Great Britain are in crisis. They have no more space to house the steadily mounting numbers of captured German soldiers. Finally, in August, America opened its borders to an emergency batch of prison- ers, marking the beginning of a little-known chapter in American history, when thousands of German soldiers marched into small town, U.S.A. More than 60 years later, that chapter is about to be reopened by a woman named Lisa Trampota, who believes the U.S. government planted a German prisoner of war camp right on her family land in Texas. Lisa Trampota: By the time I really got interested and wanted to learn more, everyone had died that knew anything about it. I’d love to learn more about my family’s history and how I’m connected with that property. Gwen: I’m Gwen Wright. I’ve come to Hearne, Texas, to find some answers to Lisa’s questions. Hi, Lisa? Lisa: Hi. Gwen: I’m Gwen. Lisa: Hi, Gwen, it’s very nice to meet you. Gwen: So, I got your phone call. Now tell me exactly what you’d like for me to find out for you. Lisa: Well, I heard, through family legend, that we owned some property outside of Hearne, and that in the 1940s the U.S. -

THE ARMY LAWYER Headquarters, Department of the Army

THE ARMY LAWYER Headquarters, Department of the Army Department of the Army Pamphlet 27-50-366 November 2003 Articles Military Commissions: Trying American Justice Kevin J. Barry, Captain (Ret.), U.S. Coast Guard Why Military Commissions Are the Proper Forum and Why Terrorists Will Have “Full and Fair” Trials: A Rebuttal to Military Commissions: Trying American Justice Colonel Frederic L. Borch, III Editorial Comment: A Response to Why Military Commissions Are the Proper Forum and Why Terrorists Will Have “Full and Fair” Trials Kevin J. Barry, Captain (Ret.), U.S. Coast Guard Afghanistan, Quirin, and Uchiyama: Does the Sauce Suit the Gander Evan J. Wallach Note from the Field Legal Cultures Clash in Iraq Lieutenant Colonel Craig T. Trebilcock The Art of Trial Advocacy Preparing the Mind, Body, and Voice Lieutenant Colonel David H. Robertson, The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center & School, U.S. Army CLE News Current Materials of Interest Editor’s Note An article in our April/May 2003 Criminal Law Symposium issue, Moving Toward the Apex: New Developments in Military Jurisdiction, discussed the recent ACCA and CAAF opinions in United States v. Sergeant Keith Brevard. These opinions deferred to findings the trial court made by a preponderance of the evidence to resolve a motion to dismiss, specifically that the accused obtained and presented forged documents to procure a fraudulent discharge. Since the publication of these opinions, the court-matial reached the ultimate issue of the guilt of the accused on remand. The court-martial acquitted the accused of fraudulent separation and dismissed the other charges for lack of jurisdiction. -

Daily Gazette Indicated a to -_____-- [ILY GAZII1[ *Call a Family Member Who Also Could Be Hazardous to Your Resident Was Charged Over $31 -S

DAILY S GAZETTE Guantanamo Bay, Cuba Vol. 41 - No. 172 -- U.S. Navy's only shore-based daily newspaper -- Wednesday, September It. t8 Benefits to affect future entrants By Mr. Casper Weinberger tion, the Congress, in its recent action on the pending .nthe past few months, there defense authorization bill, has has been considerable specula- mandated a reduction of $2.9 tion about potential changes to billion to the military the military retirement system. retirement fund. At the same The speculation, often well time, the Congress has directed intentioned but ill informed, the Department of Defense to has been based on criticism from submit options to make changes both the public and private in the retirement system for sectors about the perceived future entrants to achieve this generosity of the system. mandated reduction. The Joint Chiefs of Staff and Nonetheless, we will continue I have steadfastly maintained to insist that whatever changes that any recommendation for the Congress finally makes must change must take account of -- not adversely affect the combat first, the unique, dangerous and readiness of our forces, or vital contribution to the safety violate our firm pledges. of all of us that is made by our I want to emphasize to you service men and women: and the again, in the strongest terms, effect on combat readiness of that the dedicated men and women tampering with the effect on now serving and to those who combat readiness of tampering have retired before them, will th the retirement system. be fully protected in any nourrently we must honor the options we are required to absolute commitments that have submit to the Congress. -

Palo Alto Activity Guide

FALL/WINTER 2018 Visitors Guide to the Midpeninsula DISCOVER WHERE TO DINE, SHOP, PLAY OR RELAX Fa r m -to- table A local’s guide to seasonal dining Page 26 DestinationPaloAlto.com TOO MAJOR TOO MINOR JUST RIGHT FOR HOME FOR HOSPITAL FOR STANFORD EXPRESS CARE When an injury or illness needs quick Express Care is attention but not in the Emergency available at two convenient locations: Department, call Stanford Express Care. Stanford Express Care Staffed by doctors, nurses, and physician Palo Alto assistants, Express Care treats children Hoover Pavilion (6+ months) and adults for: 211 Quarry Road, Suite 102 Palo Alto, CA 94304 • Respiratory illnesses • UTIs (urinary tract tel: 650.736.5211 infections) • Cold and flu Stanford Express Care • Stomach pain • Pregnancy tests San Jose River View Apartment Homes • Fever and headache • Flu shots 52 Skytop Street, Suite 10 • Back pain • Throat cultures San Jose, CA 95134 • Cuts and sprains tel: 669.294.8888 Open Everyday Express Care accepts most insurance and is by Appointment Only billed as a primary care, not emergency care, 9:00am–9:00pm appointment. Providing same-day fixes every day, 9:00am to 9:00pm. Spend the evening at THE VOICE Best of MOUNTAIN VIEW 2018 THE THE VOICE Best of VOICE Best of MOUNTAIN MOUNTAIN VIEW VIEW 2016 2017 Castro Street’s Best French and Italian Food 650.968.2300 186 Castro Street, www.lafontainerestaurant.com Mountain View Welcome The Midpeninsula offers something for everyone hether you are visiting for business or pleasure, or W to attend a conference or other event at Stanford University, you will quickly discover the unusual blend of intellect, innovation, culture and natural beauty that makes up Palo Alto and the rest of the Midpeninsula. -

Love Lane Bidder Can't Meet Price

«0 - MANCHESTER HERALD. Tuesday. Sept. 10, 1985 KIT ‘N’ CARLYLE ®by Lgrry Wright MANCHESTER SPORTS WEATHER HOMES FOCUS HELP WANTED FOR SALE INESS & SERVICE DIRECTORY OH No! «*T MACC, hospital get When it’s lunchtime, 11 EC football again Clear, cool tonight; i l M • H i staying cool Thursday KfflflCIS PAiNTINR/ CAT' mental health grants mother knows best 11 senior dominated PAPERIN8 Dental Receptionist — By Owner — 3 year old, OFFQKO N ... page 2 Someone to work Sotur- l4S0 sq.ft., 7 room, 2</2 ... page 4 1 ... page 171 I ... page 11 dovs only. Monchester Pt. bath Raised Ranch. One Odd lobs. Trucking. Interior Pointing 8, Wal Corpontry and rofttodol office. Please send re Good Quality Bockhoe acre lot near East Hart- Horn* repairs. You nome lpapering — (^11 even Ing sorvlces— Qimpibto sume to Box T , c/o Man ford/Glastonbury line. ond 6kCdvotlng Work. NEuy, W, we do It. Free estf- ings, Gary McHugh, home repairs ond remo chester Herald. Quiet cul-de-sac, 2 car Bockhoe, excavation and snow plowing. No prob mafes. insured. 643-0304. 643-9321. deling. Quality work. Ref garage, flreolaced family • >. ... : . , .. • ... lem, Call Independent erences. licensed and In Hairstylist — Three full room and appliances. John Deerr'— • Painting sured. Calf 646411^. time for busy Manchester Construction Co., 456- Lawnmowers repaired - Asking $119,950. Call 649- FreeVlck up and delivery. contractor, Interior, exte salon, no following neces 0593. 10 percent senior dis rior, Insured. QuoMty All types remodeling or sary. Good benefits. Call count. Expert service. work, otf season- rotes. r(K>otrs -r- Complete kit SO Manager, Command Per Immaculate 3 bedroom Free estimates. -

The Enemy in Colorado: German Prisoners of War, 1943-46

The Enemy in Colorado: German Prisoners of War, 1943-46 BY ALLEN W. PASCHAL On 7 December 1941 , the day that would "live in infamy," the United States became directly involved in World War II. Many events and deeds, heroic or not, have been preserved as historic reminders of that presence in the world conflict. The imprisonment of American sol diers captured in combat was a postwar curiosity to many Americans. Their survival, living conditions, and treatment by the Germans became major considerations in intensive and highly publicized investigations. However, the issue of German prisoners of war (POWs) interned within the United States has been consistently overlooked. The internment centers for the POWs were located throughout the United States, with different criteria determining the locations of the camps. The first camps were extensions of large military bases where security was more easily accomplished. When the German prisoners proved to be more docile than originally believed, the camps were moved to new locations . The need for laborers most specifically dic tated the locations of the camps. The manpower that was available for needs other than the armed forces and the war industries was insuffi cient, and Colorado, in particular, had a large agricultural industry that desperately needed workers. German prisoners filled this void. There were forty-eight POW camps in Colorado between 1943 and 1946.1 Three of these were major base camps, capable of handling large numbers of prisoners. The remaining forty-five were agricultural or other work-related camps . The major base camps in Colorado were at Colorado Springs, Trinidad, and Greeley. -

'Hospitality Is the Best Form of Propaganda': German Prisoners Of

The Historical Journal of Massachusetts “Hospitality Is the Best Form of Propaganda”: German Prisoners of War in Western Massachusetts, 1944-1946.” Author: John C. Bonafilia Source: Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Volume 44, No. 1, Winter 2016, pp. 44-83. Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/number/date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.westfield.ma.edu/historical-journal/. 44 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2016 German POWs Arrive in Western Massachusetts Captured German troops enter Camp Westover Field in Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts. Many of the prisoners would go on to work as farmhands contracted out to farms in the Pioneer Valley. Undated photo. Courtesy of Air Force Historical Research Agency, Maxwell Air Force Base. 45 “Hospitality Is the Best Form of Propaganda”: German Prisoners of War in Western Massachusetts, 1944–1946 JOHN C. BONAFILIA Abstract: In October 1944, the first German prisoners of war (POWs) arrived at Camp Westover Field in Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts. Soon after, many of these prisoners were transported to farms throughout Hampshire, Franklin, and Hampden Counties to help local farmers with their harvest. The initial POW workforce numbered 250 Germans, but farmers quickly requested more to meet the demands of the community and to free up American soldiers for international service. -

MY SURVIVAL AS a PRISONER of WAR Written by Dana E

MY SURVIVAL AS A PRISONER OF WAR Written by Dana E. Morse 10136 Bryant Road Lithia, Fl. 33547 91st Bomb Group-401 Squadron Rank S/SGT Left Waist Gunner My story begins on March 6, 1944, when my plane "My Darling Also" was shot down. I heard many people coming in from all sides after I landed with a bullet hole-filled parachute, so I just lay there. I had lost a lot of blood and had no more strength. There were many civilians with guns pointed at me and they stripped me of my chute and any thing else that they wanted. The German Army came up and knocked the guns out of the hands of the civilians. I guess they were thinking of shooting me, because of all of the loud talking. I learned later that Hitler had given orders to shoot all Allied Airman. The German Army then placed me in an oxcart and it was not long before Sgt. Jim Davis came up and tried to give me some morphine, but they would not let him. By this time, I did not know if Sgt. Jim Davis had gone. All I know was that it took a long time and was a long ride. When I came to, I was on a stretcher in an old Theater, which the War Department called 9-C and was taken to a small room on the second floor where they held me down on a table. As I lay on the table, I thought that this was the end, so I fought like hell. -

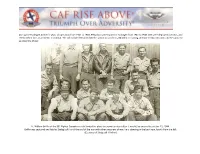

Learn More About the 32 Captured Tuskegee Airmen Pows

During the Tuskegee Airmen’s years of operation from 1941 to 1949, 992 pilots were trained in Tuskegee from 1941 to 1946. 450 were deployed overseas, and 150 lost their lives in accidents or combat. The toll included 66 pilots killed in action or accidents, 84 killed in training and non-combat missions and 32 captured as prisoners of war. Lt. William Griffin of the 99th Fighter Squadron crash-landed his plane in enemy territory after it was hit by enemy fire on Jan. 15, 1944. Griffin was captured and held at Stalag Luft I until the end of the war with other prisoners of war; he is standing in the back row, fourth from the left. (Courtesy of Stalg Luft I Online) PRISONER OF WAR MEDAL Established: 1986 Significance: Recognizes anyone who was a prisoner of war after April 5, 1917. Design: On the obverse, an American eagle with wings folded is enclosed by a ring. On the reverse, "Awarded to" is inscribed with space for the recipient's name, followed by "For honorable service while a prisoner of war" on three lines. The ribbon has a wide center stripe of black, flanked by a narrow white stripe, a thin blue stripe, a thin white stripe and a thin red stripe at the edge. Authorized device: Multiple awards are marked with a service star. MACR- Missing Air Crew Reports In May 1943, the Army Air Forces recommended the adoption of a special form, the Missing Air Crew Report (MACR), devised to record relevant facts of the last known circumstances regarding missing air crews, providing a means of integrating current data with information obtained later from other sources in an effort to conclusively determine the fate of the missing personnel.