The Pity of Partition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema CISCA thanks Professor Nirmal Kumar of Sri Venkateshwara Collega and Meghnath Bhattacharya of AKHRA Ranchi for great assistance in bringing the films to Aarhus. For questions regarding these acquisitions please contact CISCA at [email protected] (Listed by title) Aamir Aandhi Directed by Rajkumar Gupta Directed by Gulzar Produced by Ronnie Screwvala Produced by J. Om Prakash, Gulzar 2008 1975 UTV Spotboy Motion Pictures Filmyug PVT Ltd. Aar Paar Chak De India Directed and produced by Guru Dutt Directed by Shimit Amin 1954 Produced by Aditya Chopra/Yash Chopra Guru Dutt Production 2007 Yash Raj Films Amar Akbar Anthony Anwar Directed and produced by Manmohan Desai Directed by Manish Jha 1977 Produced by Rajesh Singh Hirawat Jain and Company 2007 Dayal Creations Pvt. Ltd. Aparajito (The Unvanquished) Awara Directed and produced by Satyajit Raj Produced and directed by Raj Kapoor 1956 1951 Epic Productions R.K. Films Ltd. Black Bobby Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali Directed and produced by Raj Kapoor 2005 1973 Yash Raj Films R.K. Films Ltd. Border Charulata (The Lonely Wife) Directed and produced by J.P. Dutta Directed by Satyajit Raj 1997 1964 J.P. Films RDB Productions Chaudhvin ka Chand Dev D Directed by Mohammed Sadiq Directed by Anurag Kashyap Produced by Guru Dutt Produced by UTV Spotboy, Bindass 1960 2009 Guru Dutt Production UTV Motion Pictures, UTV Spot Boy Devdas Devdas Directed and Produced by Bimal Roy Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali 1955 2002 Bimal Roy Productions -

Muhammad Umar Memon Bibliographic News

muhammad umar memon Bibliographic News Note: (R) indicates that the book is reviewed elsewhere in this issue. Abbas, Azra. ìYouíre Where Youíve Always Been.î Translated by Muhammad Umar Memon. Words Without Borders [WWB] (November 2010). [http://wordswithoutborders.org/article/youre-where-youve-alwaysbeen/] Abbas, Sayyid Nasim. ìKarbala as Court Case.î Translated by Richard McGill Murphy. WWB (July 2004). [http://wordswithoutborders.org/article/karbala-as-court-case/] Alam, Siddiq. ìTwo Old Kippers.î Translated by Muhammad Umar Memon. WWB (September 2010). [http://wordswithoutborders.org/article/two-old-kippers/] Alvi, Mohammad. The Wind Knocks and Other Poems. Introduction by Gopi Chand Narang. Selected by Baidar Bakht. Translated from Urdu by Baidar Bakht and Marie-Anne Erki. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 2007. 197 pp. Rs. 150. isbn 978-81-260-2523-7. Amir Khusrau. In the Bazaar of Love: The Selected Poetry of Amir Khusrau. Translated by Paul Losensky and Sunil Sharma. New Delhi: Penguin India, 2011. 224 pp. Rs. 450. isbn 9780670082360. Amjad, Amjad Islam. Shifting Sands: Poems of Love and Other Verses. Translated by Baidar Bakht and Marie Anne Erki. Lahore: Packages Limited, 2011. 603 pp. Rs. 750. isbn 9789695732274. Bedi, Rajinder Singh. ìMethun.î Translated by Muhammad Umar Memon. WWB (September 2010). [http://wordswithoutborders.org/article/methun/] Chughtai, Ismat. Masooma, A Novel. Translated by Tahira Naqvi. New Delhi: Women Unlimited, 2011. 152 pp. Rs. 250. isbn 978-81-88965-66-3. óó. ìOf Fists and Rubs.î Translated by Muhammad Umar Memon. WWB (Sep- tember 2010). [http://wordswithoutborders.org/article/of-fists-and-rubs/] Granta. 112 (September 2010). -

The Concept of the Perfect Man in the Thought of Ibn 'Arabiand Muhammad Iqbal: a Comparative Study

THE CONCEPT OF THE PERFECT MAN IN THE THOUGHT OF IBN 'ARABIAND MUHAMMAD IQBAL: A COMPARATIVE STUDY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate St udies and Research in partial fulfîllment of the requiremeat for the degree of Mast er of Arts Institut e of Islamic St udies Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research McGill University Mont real May 1997 National Library Bibliothbque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OnaiwaON K1AW CNtawaON K1AW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive Licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microforni, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfichelfilm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT Author : Iskandar Amel Tit le : "The Concept of the Perfect Man in the Thought of Ibn '~rabiand Muhammad Iqbal: A Comparative Study" Department : Inst it ute of Islamic St udies, McGill University, Montreal, Canada Degree : Master of Arts (M.A.) This thesis deals with the concept of the Pcrfect Man in the thought of both Ibn '~rabi(%O/ 1 165-63811 240) and Iqbal ( 1877- 1938). -

Book Pakistanonedge.Pdf

Pakistan Project Report April 2013 Pakistan on the Edge Copyright © Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, 2013 Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg, Delhi Cantt., New Delhi - 110 010 Tel. (91-11) 2671-7983 Fax.(91-11) 2615 4191 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.idsa.in ISBN: 978-93-82512-02-8 First Published: April 2013 Cover shows Data Ganj Baksh, popularly known as Data Durbar, a Sufi shrine in Lahore. It is the tomb of Syed Abul Hassan Bin Usman Bin Ali Al-Hajweri. The shrine was attacked by radical elements in July 2010. The photograph was taken in August 2010. Courtesy: Smruti S Pattanaik. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this Report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute or the Government of India. Published by: Magnum Books Pvt Ltd Registered Office: C-27-B, Gangotri Enclave Alaknanda, New Delhi-110 019 Tel.: +91-11-42143062, +91-9811097054 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.magnumbooks.org All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, sorted in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA). Contents Preface 5 Abbreviations 7 Introduction 9 Chapter 1 Political Scenario: The Emerging Trends Amit Julka, Ashok K. Behuria and Sushant Sareen 13 Chapter 2 Provinces: A Strained Federation Sushant Sareen and Ashok K. Behuria 29 Chapter 3 Militant Groups in Pakistan: New Coalition, Old Politics Amit Julka and Shamshad Ahmad Khan 41 Chapter 4 Continuing Religious Radicalism and Ever Widening Sectarian Divide P. -

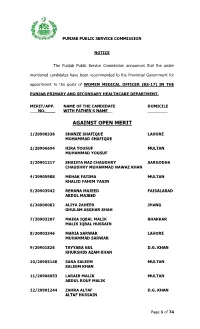

Against Open Merit

PUNJAB PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION NOTICE The Punjab Public Service Commission announces that the under mentioned candidates have been recommended to the Provincial Government for appointment to the posts of WOMEN MEDICAL OFFICER (BS-17) IN THE PUNJAB PRIMARY AND SECONDARY HEALTHCARE DEPARTMENT. MERIT/APP. NAME OF THE CANDIDATE DOMICILE NO.____ WITH FATHER'S NAME ________ AGAINST OPEN MERIT 1/20900338 SHANZE SHAFIQUE LAHORE MOHAMMAD SHAFIQUE 2/20906694 HIRA YOUSUF MULTAN MUHAMMAD YOUSUF 3/20901217 SHAISTA NAZ CHAUDHRY SARGODHA CHAUDHRY MUHAMMAD NAWAZ KHAN 4/20905988 MEHAK FATIMA MULTAN KHALID FAHIM YASIN 5/20903942 REHANA MAJEED FAISALABAD ABDUL MAJEED 6/20900082 ALIYA ZAHEER JHANG GHULAM ASGHAR SHAH 7/20903207 MAIRA IQBAL MALIK BHAKKAR MALIK IQBAL HUSSAIN 8/20903346 MARIA SARWAR LAHORE MUHAMMAD SARWAR 9/20901826 TAYYABA GUL D.G. KHAN KHURSHID AZAM KHAN 10/20905148 SARA SALEEM MULTAN SALEEM KHAN 11/20906053 LARAIB MALIK MULTAN ABDUL ROUF MALIK 12/20901244 ZAHRA ALTAF D.G. KHAN ALTAF HUSSAIN Page 1 of 74 From Pre-page 1315 posts of Women Medical Officer (BS-17) in the Punjab Primary & Secondary Healthcare Department MERIT/APP. NAME OF THE CANDIDATE DOMICILE NO.__ WITH FATHER'S NAME ________ 13/20903132 ZAHRA MUSHTAQ RAWALPINDI MUHAMMAD MUSHTAQ AHMAD 14/20901604 MARIA FATIMA OKARA QURBAN ALI 15/20901854 HAFIZA AMMARA SIDDIQI FAISALABAD MUHAMMAD SIDDIQUE 16/20904115 QURAT-UL-AIN SARWAR LAHORE MANZOOR SARWAR CHAUDHARY 17/20901733 AALIA BASHIR D.G. KHAN SHEIKH DAUD ALI 18/20905234 FARVA KOMAL M. GARH GHULAM HAIDER KHAN 19/20901333 SADIA MALIK SARGODHA GHULAM MUHAMMAD 20/20904405 ZARA MAHMOOD RAWALPINDI MAHMOOD AKHTER 21/20900565 MARIA IRSHAD HAFIZABAD IRSHAD ULLAH 22/20902101 FARYAL ASIF SARGODHA ASIF ILYAS 23/20901525 MAHAM FATIMA M. -

PEAK PERFORMANCE AGE: a DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS of PAKISTAN TEST BATSMEN Imran Abbass

PEAK PERFORMANCE AGE: A DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS OF PAKISTAN TEST BATSMEN Imran Abbass ABSTRACT The study intended to explore the relationship of age and performance of test batsmen to know at what age they achieved the peak performance while playing test cricket. Qualitative data was collected through interviews and Secondary data sources were used of different ICC (International Cricket Council) websites and magazines. Sample comprised of top 12 test players of Pakistan from past and present era, who played for Pakistan with distinction. Time series and regression analysis was executed to find the significance of the relationship between their age and performance (Batting average).The findings of the study revealed a parabolic trajectory relationship between age and their performance, positive relationship at the start and then a plateau and then a negative relationship between age and performance. The rise and decline pattern varied and majority of the cricket players touched the peak between the ages of 28 to 34 years. The current study will provide solid grounds to account the role of age in producing expert performance and strongly suggested through the evidence of data analysis that to achieve the expert performance of the enrolled test batsmen, patience is required until and unless the cricket players meet a specific age limit. Key Words: Cricket, Test Batsmen, Peak Performance, Age INTRODUCTION score of 23, Aamer nicked one to On a bright sunny morning of the Bacher in the slips and in 1997-98 winters, stage was set to adding four runs Pakistan top topple the mighty South Africans four batsman were gone to the at eastern shores. -

Swakshar Edition 3

SCREENWRITERS ASSOCIATION NEWSLETTER M A R C H 2 0 2 0 E D I T I O N 3 SWA CELEBRATES ITS 'DIAMOND JUBILEE' IN YEAR 2020! S W A A W A R D S , C O N F E R E N C E , P I T C H F E S T , W O R K S H O P S A N D V A R I O U S E V E N T S L I N E D U P Established in 1954, by stalwarts like Ramanand Sagar, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, Shailendra, Sahir Ludhianvi, Majrooh Sultanpuri and Kamal Amrohi, the Screenwriters Association (SWA; formerly the Film Writers' Association) is the strongest and the most well known trade union of film, TV and digital media writers and lyricists working in India. While the constitution of the Association was adopted in the General Body Meeting held in 1956, Film Writers’ Association, Bombay, got registered as a trade union under the Trade Union Act 1926 with Registration No. 3726 only on May 13th 1960. Thus, 2020 marks the 60th year for SWA from the day of its official functioning. The Executive Committee of SWA has planned a series of events, like SWA Awards (launch year), screenwriting workshops in prominent cities, pitching fest, the 6th edition of the Indian Screenwriters Conference (6ISC) and other events to mark the occasion. Stay tuned to SWA's official website www.swaindia.org and official social media pages for upcoming announcements. An Award for the Writer, By the Writers! A LONG-CHERISHED DREAM OF INDIAN SCREENWRITERS & LYRICISTS COMES TRUE SWA Awards 2020 are the only awards in India dedicated Hon. -

Pakistan V England: Test Records at Lord's Cricket Ground, London As at 15 May 2018

Pakistan v England: Test Records at Lord's Cricket Ground, London As at 15 May 2018. Team Records Results P W L T D 14 4 4 0 6 Highest totals 445 2006 428-8* 1982 355 1962 Lowest totals 74 2010 87 1954 100 1962 Highest 4th innings totals 214-4 2006 (Drawn) 141-8 1992 (Won) 88-3 1967 (Drawn) Largest victory margins (by inns) None Largest victory margins (by runs) 164 runs 1996 75 runs 2016 Batting Highest scores 202 Mohammad Yousuf 2006 200 Mohsin Khan 1982 187* Hanif Mohammad 1967 Most runs Name M Inns NO Runs HS Avg 100 50 Inzamam-ul-Haq 4 8 1 384 148 54.85 1 3 Mohsin Khan 2 4 1 316 200 105.33 1 0 Mohammad Yousuf 3 6 0 292 202 48.66 1 0 Hanif Mohammad 3 5 1 283 187 * 70.75 1 0 Saeed Anwar 2 4 0 182 88 45.50 0 2 Most centuries No batsman has scored more than 1 century. Fastest fifty (balls) 40 Umar Akmal 2010 Fastest century (balls) 153 Mohsin Khan 1982 Record wicket partnerships 1st 136 Saeed Anwar and Shadab Kabir 1996 2nd 144 Mohsin Khan and Mansoor Akhtar 1982 3rd 130 Saeed Anwar and Inzamam-ul-Haq 1996 4th 153 Mohsin Khan and Zaheer Abbas 1982 5th 197 Javed Burki and Nasim-ul-Ghani 1962 6th 59 Mohammad Yousuf and Abdul Razzaq 2006 7th 99 Mohammad Yousuf and Kamran Akmal 2006 8th 130 Hanif Mohammad and Asif Iqbal 1967 9th 46* Wasim Akram and Waqar Younis 1992 10th 50 Rashid Latif and Ata-ur-Rehman 1996 10th 50 Umar Akmal and Mohammad Asif 2010 Bowling Best bowling in an innings 6-32 Mudassar Nazar 1982 6-72 Yasir Shah 2016 6-84 Mohammad Aamer 2010 Best bowling in a match 10-141 Yasir Shah 2016 8-154 Waqar Younis 1996 7-131 Waqar Younis -

1St Merit List Open Candidates (Emergency Radio RT Dialysis).Pdf

1ST MERIT LIST OF OPEN CANDIDATES (DIALYSIS) DISCIPLINE SESSION 2020 DURAN PUR CAMPUS SHORTLISTED CANDIDATES ARE REQUIRED TO APPEAR BEFORE THE ADMISSION COMMITTEE ALONG WITH ORIGINAL DOCUMENTS ON 09 DECEMBER, 2020 AT 09:00 AM, IN THE OFFICE OF THE DIRECTOR, KMU-IPMS, DURANPUR, PESHAWAR, POSITIVELY. Errors & omissions are subject to subsequent ractification s# (10%) (50%) (40%) Name Marks Obtain MARKS MARKS Domicile (M/D/Y) SSC Total REMARKS Entry Test Entry Test HSSC Total SSC Obtain HSSC %age IMPROVED Merit Merit Score %age Marks HSSC Obtain HSSC Obtain Passing Year Passing Year Passing Date of Date Birth of Gender (M/F) Gender Father's Name Father's SCC weightage Weightage Test Weightage Adjusted Marks Adjusted Entry Test Total Weightage HSSC Weightage SSC % age Marks SHORTLISTED FOR INTERVIEW 1 Areeba Mukhtar Mukhtar Hussain F 9/17/2000 Mansehra 1009 1100 2017 91.73 932 1100 2019 932 84.73 81 100 81.00 9.17 42.36 32.4 83.94 SHORTLISTED FOR INTERVIEW 2 Waqas khan Khaliq dad khan M 1/8/2002 Swat 946 1100 2018 86.00 944 1100 2020 944 85.82 80 100 80.00 8.60 42.91 32 83.51 SHORTLISTED FOR INTERVIEW 3 Salman Ahmad Abdul Hamid M 3/6/1999 Swat 952 1100 2015 86.55 939 1100 2018 929 84.45 81 100 81.00 8.65 42.23 32.4 83.28 MI SHORTLISTED FOR INTERVIEW 4 Muhammad Arsalan Azam Rizwan Ullah M 3/4/2002 Charsadda 1030 1100 2017 93.64 930 1100 2019 930 84.55 78 100 78.00 9.36 42.27 31.2 82.84 SHORTLISTED FOR INTERVIEW 5 Abdul Haseeb Khatak Farman Ullah M 11/4/2000 Peshawar 1006 1100 2017 91.45 937 1100 2020 927 84.27 78 100 78.00 9.15 42.14 31.2 -

A Stranger in My Own Country East Pakistan 1969-1974

A Stranger in Ny Own Contry East Pakistan, 1969-1971 repreoduced by Sani H. Panhwar A Stra nger inm yow n c ountry Ea stPa kista n, 1969-1971 Ma jor Genera l (Retd) Kha dim Hussa inRa ja Reproducedb y Sa niH. Pa nhw a r C O N TEN TS Introduction By Muhammad Reza Kazimi .. .. .. .. .. 1 Chapter 1 The Brewing Storm .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 Chapter 2 Prelude to the 1970 Elections .. .. .. .. .. .. 13 Chapter 3 The Rising Sun of the Awami League .. .. .. .. .. 22 Chapter 4 The Devastating Cyclone of November 1970 .. .. .. .. 26 Chapter 5 A No-Win Situation .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 28 Chapter 6 The Crisis Deepens .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 32 Chapter 7 Lt. Gen. Tikka Khan in Action .. .. .. .. .. .. 42 Chapter 8 Operation Searchlight .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 50 Chapter 9 Last Words . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 63 Appendix A .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 70 Appendix B .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 71 Appendix C .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 78 Introduction B y M uham m adReza Kazim i History, it is often said, 'is written by victors'. In the case of East Pakistan, it has been written by the losers. One general,1 one lieutenant general,2 four major generals,3 and two brigadiers4 have given their account of the events leading to the secession of East Pakistan. Some of their compatriots, who witnessed or participated in the event, are still reluctant to publish their impressions. The credibility of such accounts depends on whether they were written for self-justification or for introspection. The utility of such accounts depends on whether they are relevant. On both counts, these recollections of the late Major General Khadim Hussain Raja are of definite value. They are candid and revealing; they are also imbued with respect for the opposite point of view. -

A Linguistic Critique of Pakistani-American Fiction

CULTURAL AND IDEOLOGICAL REPRESENTATIONS THROUGH PAKISTANIZATION OF ENGLISH: A LINGUISTIC CRITIQUE OF PAKISTANI-AMERICAN FICTION By Supervisor Muhammad Sheeraz Dr. Muhammad Safeer Awan 47-FLL/PHDENG/F10 Assistant Professor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English To DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF LANGUAGES AND LITERATURE INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD April 2014 ii iii iv To my Ama & Abba (who dream and pray; I live) v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I owe special gratitude to my teacher and research supervisor, Dr. Muhammad Safeer Awan. His spirit of adventure in research, the originality of his ideas in regard to analysis, and the substance of his intellect in teaching have guided, inspired and helped me throughout this project. Special thanks are due to Dr. Kira Hall for having mentored my research works since 2008, particularly for her guidance during my research at Colorado University at Boulder. I express my deepest appreciation to Mr. Raza Ali Hasan, the warmth of whose company made my stay in Boulder very productive and a memorable one. I would also like to thank Dr. Munawar Iqbal Ahmad Gondal, Chairman Department of English, and Dean FLL, IIUI, for his persistent support all these years. I am very grateful to my honorable teachers Dr. Raja Naseem Akhter and Dr. Ayaz Afsar, and colleague friends Mr. Shahbaz Malik, Mr. Muhammad Hussain, Mr. Muhammad Ali, and Mr. Rizwan Aftab. I am thankful to my friends Dr. Abdul Aziz Sahir, Dr. Abdullah Jan Abid, Mr. Muhammad Awais Bin Wasi, Mr. Muhammad Ilyas Chishti, Mr. Shahid Abbas and Mr. -

PRINT CULTURE and LEFT-WING RADICALISM in LAHORE, PAKISTAN, C.1947-1971

PRINT CULTURE AND LEFT-WING RADICALISM IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN, c.1947-1971 Irfan Waheed Usmani (M.Phil, History, University of Punjab, Lahore) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my original work and it has been written by me in its entirety. I have duly acknowledged all the sources of information which have been used in the thesis. This thesis has also not been submitted for any degree in any university previously. _________________________________ Irfan Waheed Usmani 21 August 2015 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First I would like to thank God Almighty for enabling me to pursue my higher education and enabling me to finish this project. At the very outset I would like to express deepest gratitude and thanks to my supervisor, Dr. Gyanesh Kudaisya, who provided constant support and guidance to this doctoral project. His depth of knowledge on history and related concepts guided me in appropriate direction. His interventions were both timely and meaningful, contributing towards my own understanding of interrelated issues and the subject on one hand, and on the other hand, injecting my doctoral journey with immense vigour and spirit. Without his valuable guidance, support, understanding approach, wisdom and encouragement this thesis would not have been possible. His role as a guide has brought real improvements in my approach as researcher and I cannot measure his contributions in words. I must acknowledge that I owe all the responsibility of gaps and mistakes in my work. I am thankful to his wife Prof.