The Concept of the Perfect Man in the Thought of Ibn 'Arabiand Muhammad Iqbal: a Comparative Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ALAN WILLIAMS Full Interview Final

The Operation of Divine Love An Interview with Alan Williams by David Hornsby, January 2020 What would you say is the profound and universal message of the Masnavi? I’ve been thinking about this for a very long time. The main message cannot easily be put into intellectual terms, and that is the problem, and why Rumi addresses the reader through poetry: poetry immediately addresses a different level of the mind from the literal, intellectual mind. The message is intended for the inner being or higher mind. And, to hear this message, one has to be very patient and attentive. The message is about the realisation of union with our true reality – but that is a conditional promise of a result, if you like, because we have to give up everything in order to know union, and very few of us are able or prepared to do that. Rumi went to great pains to explain what he meant in the best possible way, through ordinary language, through stories and fables, but also by direct conversation with his readers, guiding them along the way. This is really what I talk about in my Introduction to the first book, that he has a way of leading the reader into a receptive state so that it is easier to understand what he has to say: to contemplate subtle realities that are much subtler than what we are normally used to reading in ordinary literature, even in other Persian, Sufi poetry. One of the people commenting on your books, Ahmad Karimi Hakkak, has said that they are “intensely relevant not just to our time, but to all humanity through the millennia”. -

1St Merit List Open Candidates (Emergency Radio RT Dialysis).Pdf

1ST MERIT LIST OF OPEN CANDIDATES (DIALYSIS) DISCIPLINE SESSION 2020 DURAN PUR CAMPUS SHORTLISTED CANDIDATES ARE REQUIRED TO APPEAR BEFORE THE ADMISSION COMMITTEE ALONG WITH ORIGINAL DOCUMENTS ON 09 DECEMBER, 2020 AT 09:00 AM, IN THE OFFICE OF THE DIRECTOR, KMU-IPMS, DURANPUR, PESHAWAR, POSITIVELY. Errors & omissions are subject to subsequent ractification s# (10%) (50%) (40%) Name Marks Obtain MARKS MARKS Domicile (M/D/Y) SSC Total REMARKS Entry Test Entry Test HSSC Total SSC Obtain HSSC %age IMPROVED Merit Merit Score %age Marks HSSC Obtain HSSC Obtain Passing Year Passing Year Passing Date of Date Birth of Gender (M/F) Gender Father's Name Father's SCC weightage Weightage Test Weightage Adjusted Marks Adjusted Entry Test Total Weightage HSSC Weightage SSC % age Marks SHORTLISTED FOR INTERVIEW 1 Areeba Mukhtar Mukhtar Hussain F 9/17/2000 Mansehra 1009 1100 2017 91.73 932 1100 2019 932 84.73 81 100 81.00 9.17 42.36 32.4 83.94 SHORTLISTED FOR INTERVIEW 2 Waqas khan Khaliq dad khan M 1/8/2002 Swat 946 1100 2018 86.00 944 1100 2020 944 85.82 80 100 80.00 8.60 42.91 32 83.51 SHORTLISTED FOR INTERVIEW 3 Salman Ahmad Abdul Hamid M 3/6/1999 Swat 952 1100 2015 86.55 939 1100 2018 929 84.45 81 100 81.00 8.65 42.23 32.4 83.28 MI SHORTLISTED FOR INTERVIEW 4 Muhammad Arsalan Azam Rizwan Ullah M 3/4/2002 Charsadda 1030 1100 2017 93.64 930 1100 2019 930 84.55 78 100 78.00 9.36 42.27 31.2 82.84 SHORTLISTED FOR INTERVIEW 5 Abdul Haseeb Khatak Farman Ullah M 11/4/2000 Peshawar 1006 1100 2017 91.45 937 1100 2020 927 84.27 78 100 78.00 9.15 42.14 31.2 -

Birth of a Tragedy Kashmir 1947

A TRAGEDY MIR BIRTH OF A TRAGEDY KASHMIR 1947 Alastair Lamb Roxford Books Hertingfordbury 1994 O Alastair Lamb, 1994 The right of Alastair Lamb to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published in 1994 by Roxford Books, Hertingfordbury, Hertfordshire, U.K. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the publishers. ISBN 0 907129 07 2 Printed in England by Redwood Books, Trowbridge, Wiltshire Typeset by Create Publishing Services Ltd, Bath, Avon Contents Acknowledgements vii I Paramountcy and Partition, March to August 1947 1 1. Introductory 1 2. Paramountcy 4 3. Partition: its origins 13 4. Partition: the Radcliffe Commission 24 5. Jammu & Kashmir and the lapse of Paramountcy 42 I1 The Poonch Revolt, origins to 24 October 1947 54 I11 The Accession Crisis, 24-27 October 1947 81 IV The War in Kashmir, October to December 1947 104 V To the United Nations, October 1947 to 1 January 1948 1 26 VI The Birth of a Tragedy 165 Maps 1. The State of Jammu & Kashmir in relation to its neighbours. ix 2. The State ofJammu & Kashmir. x 3. Stages in the creation of the State ofJammu and Kashmir. xi 4. The Vale of Kashmir. xii ... 5. Partition boundaries in the Punjab, 1947. xlll Acknowledgements ince the publication of my Karhmir. A Disputed Legmy 1846-1990 in S199 1, I have been able to carry out further research into the minutiae of those events of 1947 which resulted in the end ofthe British Indian Empire, the Partition of the Punjab and Bengal and the creation of Pakistan, and the opening stages of the Kashmir dispute the consequences of which are with us still. -

125390877.Pdf

PETER LAMBORN WILSON IBLIS, THE BLACK LIGHT SATANISM IN ISLAM I had a Persian friend in Tehran, an avant-garde playwright and member of a sect called Ahl-i Haqq (“People of Truth” or “People of God,” “haqq” being a divine name) who traveled to the valley of the Satan-worshippers in the mid-1970s. A Kurdish sect influenced by extreme Shi'ism, Sufism, Iranian gnosticism, and native shamanism, the Ahl-i Haqq consists of a number of subgroups, most of whose adherents are non-literate peasants. With no Sacred Book to unite these subgroups in their remote valleys, they often developed widely divergent versions of the Ahl-i Haqq myths and teachings. One subgroup venerates Satan. I know of almost nothing written about the Shaitan-parastiyyan or “Satan-worshippers,”1 and not much has been done on the Ahl-i Haqq in general.2 Many secrets remain unknown to outsiders. The Tehran Ahl-i Haqq were led by a Kurdish pir, Ustad Nur Ali Elahi, a great musician and teacher.3 Some old-fashioned Ahl-i Haqq considered him a renegade because he revealed secrets to outsiders, i.e., non-Kurds, and even published them in books. When my friend asked him about the Satan-worshippers, however, Elahi gently rebuffed him: “Don't worry about Shaitan; worry about the shay-ye tan” (literally “the thing of the body,” the carnal soul, the separative ego). My Friend ignored this doubtless good advice, and with his brother set off for Kurdestan in their Land Rover. You have no idea how remote some parts of Asia can be unless you've been there; not even a helicopter could penetrate those jagged peaks and dedicated ravines. -

Muhammad Iqbal – Reconstructing Islam Along Occidental Lines of Thought

Interdisciplinary Journal for Religion and Transformation in Contemporary Society 5 (2019) 201–229 brill.com/jrat Muhammad Iqbal – Reconstructing Islam along Occidental Lines of Thought Stephan Popp Institute of Iranian Studies, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Hollandstrasse 11–13, 1020 Vienna, Austria [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract The philosopher Muhammad Iqbal is officially seen as the inventor of the idea of Pakistan and is considered to be the national poet of the country. Indeed, he is one of the most important Islamic modernists, a source of inspiration for enlightened Islam today, and one of the great philosophers of life in the first half of the 20th century. This article explains the main concepts of philosophy: “self”, “love”, “intuition”, his philoso- phy of time, his concept of Islam, and his critique of the West. It then traces the in- fluences on his thought from Islamic thinkers, from the Western philosophers Fichte, Kant, Nietzsche, and Bergson, and the Influence of the Indian society he was living in. Iqbal claimed that all his ideas derived from his thorough reading of the Quran. However, the questions that shaped his answers were very much in the form of the European philosophy of the time, and in that of the discourses of his society too. Keywords Philosophy (1900–1940) – Pakistan – modern Islam – Allama Muhammad Iqbal 1 Introduction Muhammad Iqbal from Lahore, then British India, is not very well known in German- speaking countries. Yet, he can be regarded as one of the great rep- resentatives of the philosophy of life (“Lebensphilosophie”) beside Nietzsche and Bergson, both of whom he had studied. -

{FREE} Divine Governance of the Human Kingdom

DIVINE GOVERNANCE OF THE HUMAN KINGDOM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Muhyi al-Din Muhammad ibn 'Ali Ibn al-'Arabi | 302 pages | 19 Jan 2001 | Fons Vitae,US | 9781887752053 | English | Kentucky, United States Divine Governance of the Human Kingdom Published by Fons Vitae I was however heartened to read later on that Ibn Arabi actively encourage people to work as opposed to sitting down and praying. All in all, a good expose into the inner and outer world of Ibn Arabi. Feb 23, Lumumba Shakur rated it really liked it Shelves: sufi-studies , second-look. This is probably the most accessible treatise by Ibn Arabi that I've had the good pleasure to have read. That may be due to Shaykh Tosun Bayrak's translation style. It has been a while since I have read it, but I do recall that I enjoined all three selections that are in this publication. This is translation of Ibn Arabi's that I want to read again. Dec 25, Leon Del canto rated it it was amazing. Very accessible and highly recommended to those interested in Islamic spirituality. Faraaz rated it liked it Dec 06, Mahmoud Khalifa rated it it was amazing Jan 01, Bilal rated it it was amazing Mar 17, Qasem rated it it was amazing Dec 27, Andrew rated it it was amazing Oct 13, Zayn Gregory rated it liked it Dec 17, Miraltaf rated it it was ok Feb 13, Muara rated it it was amazing Jan 12, Yasmine Kamel rated it it was amazing Mar 19, Daaniyaal rated it it was amazing Nov 06, Roz Tremain rated it it was amazing Nov 14, Mechthild von Magdeburg rated it it was amazing Nov 05, Ibnalarabi Greatestmaster rated it it -

6455.Pdf, PDF, 1.27MB

Overall List Along With Domicile and Post Name Father Name District Post Shahab Khan Siraj Khan PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Sana Ullah Muhammad Younas Lower Dir 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Mahboob Ali Fazal Rahim Swat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Tahir Saeed Saeed Ur Rehman Kohat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Owais Qarni Raham Dil Lakki Marwat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Ashfaq Ahmad Zarif Khan Charsadda 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Saud Khan Haji Minak Khan Khyber 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Qamar Jan Syed Marjan Kurram 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Kamil Khan Wakeel Khan PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Waheed Gul Muhammad Qasim Lakki Marwat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Tanveer Ahmad Mukhtiar Ahmad Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muhammad Faheem Muhammad Aslam PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muslima Bibi Jan Gul Dera Ismail Khan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muhammad Zahid Muhammad Saraf Batagram 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Riaz Khan Muhammad Anwar Lower Dir 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Bakht Taj Abdul Khaliq Shangla 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Hidayat Ullah Fazal Ullah Swabi 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Wajid Ali Malang Jan Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Sahar Rashed Abdur Rasheed Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Afsar Khan Afridi Ghulam Nabi PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Adnan Khan Manazir Khan Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Liaqat Ali Malik Aman Charsadda 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Adnan Iqbal Parvaiz Khan Mardan 01. -

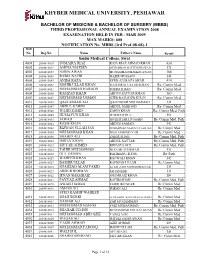

3Rd Prof MBBS 2008-A

KHYBER MEDICAL UNIVERSITY, PESHAWAR BACHELOR OF MEDICINE & BACHELOR OF SURGERY (MBBS) THIRD PROFESSIONAL ANNUAL EXAMINATION 2008 EXAMINATION HELD IN FEB - MAR 2009 MAX MARKS: 600 NOTIFICATION No. MBBS (3rd Prof-08-08)-1 Roll No. Reg.No. Name Father's Name Result Saidu Medical College, Swat 4001 2004810018 SUMAIRA RIAZ RAJA RIAZ AHMAD KHAN 434 4002 2004810019 AMINA MATEEN MUHAMMAD MATEEN KHAWAJA 376 4003 2004810053 SOBIA AWAN MUHAMMAD MASKIN AWAN 386 4004 2004810054 RABIA NAZIR NAZIR HUSSAIN 348 4005 2004810055 ANISA RAZA SYED ALI RAZA SHAH 414 4006 2004810052 MOHIB ULLAH KHAN HAJI SIRAJ ULLAH KHAN Re: Comm Med 4007 2004810051 MUHAMMAD HAROON SHERA KHAN Re: Comm Med 4008 2004810050 RAMZAN KHAN ABDUS SATTAR KHAN 363 4009 2004810049 MUHAMMAD USMAN SHER BAHADUR KHAN Re: Comm Med 4010 2004810048 QAZI AMJAD ALI QAZI NISAR MUHAMMAD 331 4011 2004810047 ABDUL KARIM ABDUL MABOOD Re: Comm Med 4012 2004810046 WAJID ZAHID ZAHID KHAN Re: Comm Med, Path 4013 2004810085 HUMAYUN KHAN WAHEED GUL 396 4014 2004810043 JAWAD MUKHTIAR HUSSAIN Re: Comm Med, Path 4015 2004810044 RASIF KHAN ABDUS SAMAD 342 4016 2004810042 RIZWAN ULLAH JAN MUHAMMAD NAEEM ULLAH JAN Re: Comm Med 4017 2004810038 MUHAMMAD KHAN MUHAMMAD YAR Re: Comm Med 4018 2004810036 SHAHID ALI ZAHIR SHAH Re: Comm Med, Path 4019 2004810034 IMRAN KHAN ABDUL SATTAR Re: Comm Med, Path 4020 2004810033 SIYYAR AHMED KHIASTA GUL Re: Comm Med, Path 4021 2004810032 TAHIR MUHAMMAD NIAZ MUHAMMAD 315 4022 2004810030 GUL ZAMAN RAHMANU-D-DIN Re: Path 4023 2004810029 WAHEED KHAN RAJ WALI KHAN 345 4024 2004810027 -

The Case of American Sufi Movements1

HYBRIDIDENTITY FORMATIONS IN MUSLIMAMERICA Hybrid Identity Formations in Muslim America: The Case of American Sufi Movements’ Marcia Hermansen Loyola University Chicago, Illinois he minimal attention given to Sufi movements in much previous scholarship on Muslims in America’ is indicative of the assumption T that these movements were marginal to the concerns of most Muslims living in the United States and insignificant in terms of their impact on American culture and institution^.^ At the same time, organizations and publications sponsored by the American Muslim community have largely ignored S~fism.~One academic study called Sufis “the hidden Muslims” of America since they had been largely overlooked by the few sociological studies of American Muslim communities, and because, in many cases, adherents do not attend mosques or belong to mainstream Islamic organi- zations .5 The following study contends that these movements are worthy of attention and that their impact in terms of both the Muslim community and American culture is significant and increasing. The literary output of American Sufi movements is by now so vast that it would require a volume rather than an essay to adequately present the history and doctrines of each of the groups in detail. I therefore aim to provide an overview of major groups, their history and their activities. There is a range of movements that can be considered Sufi-oriented, or that have been influenced to various degrees by the tradition of Islamic mysticism. It is not within the scope of this paper to evaluate the authentici- ty of any movement or individual. However, if the standard for terming a movement “Sufi”were to mean the practice of Islamic law, not all of these movements would be included. -

The Seljukid, Karamanoğlu and the Ottoman Periods, 1200-1512

ZÂVİYE-KHANKÂHS AND RELIGIOUS ORDERS IN THE PROVINCE OF KARAMAN: THE SELJUKID, KARAMANOĞLU AND THE OTTOMAN PERIODS, 1200-1512 A Ph.D. Dissertation by FATİH BAYRAM Department of History Bilkent University Ankara September 2008 To my grandfather ZÂVİYE-KHANKÂHS AND RELIGIOUS ORDERS IN THE PROVINCE OF KARAMAN: THE SELJUKID, KARAMANOĞLU AND THE OTTOMAN PERIODS, 1200-1512 The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by FATİH BAYRAM In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BİLKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2008 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. -------------------------------- Prof. Dr. Halil İnalcık Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. -------------------------------- Prof. Dr. Mustafa Kara Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. -------------------------------- Asst. Prof. Mehmet Kalpaklı Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. -------------------------------- Asst. Prof. Evgeni R. Radushev Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. -

Unclaimed Deposit 2014

Details of the Branch DETAILS OF THE DEPOSITOR/BENEFICIARIYOF THE INSTRUMANT NAME AND ADDRESS OF DEPOSITORS DETAILS OF THE ACCOUNT DETAILS OF THE INSTRUMENT Transaction Federal/P rovincial Last date of Name of Province (FED/PR deposit or in which account Instrume O) Rate Account Type Currency Rate FCS Rate of withdrawal opened/instrume Name of the nt Type In case of applied Amount Eqv.PKR Nature of Deposit ( e.g Current, (USD,EUR,G Type Contract PKR (DD-MON- Code Name nt payable CNIC No/ Passport No Name Address Account Number applicant/ (DD,PO, Instrument NO Date of issue instrumen date Outstandi surrender (LCY,UFZ,FZ) Saving, Fixed BP,AED,JPY, (MTM,FC No (if conversio YYYY) Purchaser FDD,TDR t (DD-MON- ng ed or any other) CHF) SR) any) n , CO) favouring YYYY) the Governm ent 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 PRIX 1 Main Branch Lahore PB Dir.Livestock Quetta MULTAN ROAD, LAHORE. 54500 LCY 02011425198 CD-MISC PHARMACEUTICA TDR 0000000189 06-Jun-04 PKR 500 12-Dec-04 M/S 1 Main Branch Lahore PB MOHAMMAD YUSUF / 1057-01 LCY CD-MISC PKR 34000 22-Mar-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB BHATTI EXPORT (PVT) LTD M/S BHATTI EXPORT (PVT) LTD M/SLAHORE LCY 2011423493 CURR PKR 1184.74 10-Apr-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB ABDUL RAHMAN QURESHI MR ABDUL RAHMAN QURESHI MR LCY 2011426340 CURR PKR 156 04-Jan-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB HAZARA MINERAL & CRUSHING IND HAZARA MINERAL & CRUSHING INDSTREET NO.3LAHORE LCY 2011431603 CURR PKR 2764.85 30-Dec-04 "WORLD TRADE MANAGEMENT M/SSUNSET LANE 1 Main Branch Lahore PB WORLD TRADE MANAGEMENT M/S LCY 2011455219 CURR PKR 75 19-Mar-04 NO.4,PHASE 11 EXTENTION D.H.A KARACHI " "BASFA INDUSTRIES (PVT) LTD.FEROZE PUR 1 Main Branch Lahore PB 0301754-7 BASFA INDUSTRIES (PVT) LTD. -

Love in the Writings of Ibn 'Arabī

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2020-12-01 Love in the Writings of Ibn ‘Arabī Ibrahim, Hany Talaat Ahmed Ibrahim, H. T. A. (2020). Love in the Writings of Ibn ‘Arabī (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/112804 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Love in the Writings of Ibn ‘Arabī by Hany Talaat Ahmed Ibrahim A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA DECEMBER, 2020 © Hany Talaat Ahmed Ibrahim 2020 Abstract This thesis aims to explore the theory of love in the writings of the Andalusian Sufi Ibn ‘Arabī (d. 1240 CE). It begins by examining Love, both the nature of Divine and human love, as has been passionately declared in the writings of many of the Sufi masters that preceded Ibn ‘Arabī before turning to the views of the Sufi master himself. The doctrine of Divine love as outlined by many of the Sufis revolves mainly around two important Qur’anic verses, and three hadiths.