Empirical Studies of Nature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Press Release

Press Contacts Patrick Milliman 212.590.0310, [email protected] Alanna Schindewolf 212.590.0311, [email protected] THE MORGAN HOSTS MAJOR EXHIBITION OF MASTER DRAWINGS FROM MUNICH’S FAMED STAATLICHE GRAPHISCHE SAMMLUNG SHOW INCLUDES WORKS FROM THE RENAISSANCE TO THE MODERN PERIOD AND MARKS THE FIRST TIME THE GRAPHISCHE SAMMLUNG HAS LENT SUCH AN IMPORTANT GROUP OF DRAWINGS TO AN AMERICAN MUSEUM Dürer to de Kooning: 100 Master Drawings from Munich October 12, 2012–January 6, 2013 **Press Preview: Thursday, October 11, 10 a.m. until 11:30 a.m.** RSVP: (212) 590-0393, [email protected] New York, NY, August 25, 2012—This fall, The Morgan Library & Museum will host an extraordinary exhibition of rarely- seen master drawings from the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich, one of Europe’s most distinguished drawings collections. On view October 12, 2012– January 6, 2013, Dürer to de Kooning: 100 Master Drawings from Munich marks the first time such a comprehensive and prestigious selection of works has been lent to a single exhibition. Johann Friedrich Overbeck (1789–1869) Italia and Germania, 1815–28 Dürer to de Kooning was conceived in Inv. 2001:12 Z © Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München exchange for a show of one hundred drawings that the Morgan sent to Munich in celebration of the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung’s 250th anniversary in 2008. The Morgan’s organizing curators were granted unprecedented access to the Graphische Sammlung’s vast holdings, ultimately choosing one hundred masterworks that represent the breadth, depth, and vitality of the collection. The exhibition includes drawings by Italian, German, French, Dutch, and Flemish artists of the Renaissance and baroque periods; German draftsmen of the nineteenth century; and an international contingent of modern and contemporary draftsmen. -

Oil Sketches and Paintings 1660 - 1930 Recent Acquisitions

Oil Sketches and Paintings 1660 - 1930 Recent Acquisitions 2013 Kunsthandel Barer Strasse 44 - D-80799 Munich - Germany Tel. +49 89 28 06 40 - Fax +49 89 28 17 57 - Mobile +49 172 890 86 40 [email protected] - www.daxermarschall.com My special thanks go to Sabine Ratzenberger, Simone Brenner and Diek Groenewald, for their research and their work on the text. I am also grateful to them for so expertly supervising the production of the catalogue. We are much indebted to all those whose scholarship and expertise have helped in the preparation of this catalogue. In particular, our thanks go to: Sandrine Balan, Alexandra Bouillot-Chartier, Corinne Chorier, Sue Cubitt, Roland Dorn, Jürgen Ecker, Jean-Jacques Fernier, Matthias Fischer, Silke Francksen-Mansfeld, Claus Grimm, Jean- François Heim, Sigmar Holsten, Saskia Hüneke, Mathias Ary Jan, Gerhard Kehlenbeck, Michael Koch, Wolfgang Krug, Marit Lange, Thomas le Claire, Angelika and Bruce Livie, Mechthild Lucke, Verena Marschall, Wolfram Morath-Vogel, Claudia Nordhoff, Elisabeth Nüdling, Johan Olssen, Max Pinnau, Herbert Rott, John Schlichte Bergen, Eva Schmidbauer, Gerd Spitzer, Andreas Stolzenburg, Jesper Svenningsen, Rudolf Theilmann, Wolf Zech. his catalogue, Oil Sketches and Paintings nser diesjähriger Katalog 'Oil Sketches and Paintings 2013' erreicht T2013, will be with you in time for TEFAF, USie pünktlich zur TEFAF, the European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht, the European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht. 14. - 24. März 2013. TEFAF runs from 14-24 March 2013. Die in dem Katalog veröffentlichten Gemälde geben Ihnen einen The selection of paintings in this catalogue is Einblick in das aktuelle Angebot der Galerie. Ohne ein reiches Netzwerk an designed to provide insights into the current Beziehungen zu Sammlern, Wissenschaftlern, Museen, Kollegen, Käufern und focus of the gallery’s activities. -

Page, Canvas, Wall: Visualising the History Of

Title Page, Canvas, Wall: Visualising the History of Art Type Article URL https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/15882/ Dat e 2 0 2 0 Citation Giebelhausen, Michaela (2020) Page, Canvas, Wall: Visualising the History of Art. FNG Research (4/2020). pp. 1-14. ISSN 2343-0850 Cr e a to rs Giebelhausen, Michaela Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected] . License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author Issue No. 4/2020 Page, Canvas, Wall: Visualising the History of Art Michaela Giebelhausen, PhD, Course Leader, BA Culture, Criticism and Curation, Central St Martins, University of the Arts, London Also published in Susanna Pettersson (ed.), Inspiration – Iconic Works. Ateneum Publications Vol. 132. Helsinki: Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum, 2020, 31–45 In 1909, the Italian poet and founder of the Futurist movement, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti famously declared, ‘[w]e will destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind’.1 He compared museums to cemeteries, ‘[i]dentical, surely, in the sinister promiscuity of so many bodies unknown to one another… where one lies forever beside hated or unknown beings’. This comparison of the museum with the cemetery has often been cited as an indication of the Futurists’ radical rejection of traditional institutions. It certainly made these institutions look dead. With habitual hyperbole Marinetti claimed: ‘We stand on the last promontory of the centuries!… Why should we look back […]? Time and Space died yesterday.’ The brutal breathlessness of Futurist thinking rejected all notions of a history of art. -

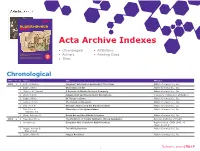

Acta Archive Indexes Directory

VOLUME 50, NO. 1 | 2017 ALDRICHIMICA ACTA Acta Archive Indexes • Chronological • Affiliations 4-Substituted Prolines: Useful Reagents in Enantioselective HIMICA IC R A Synthesis and Conformational Restraints in the Design of D C L T Bioactive Peptidomimetics A A • Authors • Painting Clues Recent Advances in Alkene Metathesis for Natural Product Synthesis—Striking Achievements Resulting from Increased 1 7 9 1 Sophistication in Catalyst Design and Synthesis Strategy 68 20 • Titles The life science business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany operates as MilliporeSigma in the U.S. and Canada. Chronological YEAR Vol. No. Authors Title Affiliation 1968 1 1 Buth, William F. Fragment Information Retrieval of Structures Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 1 Bader, Alfred Chemistry and Art Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 1 Higbee, W. Edward A Portrait of Aldrich Chemical Company Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 2 West, Robert Squaric Acid and the Aromatic Oxocarbons University of Wisconsin at Madison 2 Bader, Alfred Of Things to Come Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 3 Koppel, Henry The Compleat Chemists Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 3 Biel, John H. Biogenic Amines and the Emotional State Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 4 Biel, John H. Chemistry of the Quinuclidines Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. Warawa, E.J. 4 Clark, Anthony M. Dutch Art and the Aldrich Collection Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 1969 2 1 May, Everette L. The Evolution of Totally Synthetic, Strong Analgesics National Institutes of Health 1 Anonymous Computer Aids Search for R&D Chemicals Reprinted from C&EN 1968, 46 (Sept. 2), 26-27 2 Hopps, Harvey B. The Wittig Reaction Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. Biel, John H. -

Bernheimer – Colnaghi Announce Their Collection Being Exhibited at TEFAF, Maastricht, 7 – 16 March 2008. Submitted By: Cassleton Elliott Thursday, 14 February 2008

Bernheimer – Colnaghi announce their collection being exhibited at TEFAF, Maastricht, 7 – 16 March 2008. Submitted by: Cassleton Elliott Thursday, 14 February 2008 Among the highlights of the Bernheimer-Colnaghi stand at TEFAF, Maastricht, is Lucas Cranach the Elder’s Aristotle and Phyllis. The humiliation of the Greek philosopher Aristotle was one of the most powerful and popular pictorial examples of the theme of Weibermacht or the ‘Power of Women’. Aristotle is said to have admonished one of his students (traditionally identified as Alexander the Great) for paying too much attention to Phyllis, a woman of the court. She got her revenge by seducing the philosopher and persuading him to allow her to ride on his back in return for the promise of sexual favours. The picture can be linked to a group of paintings of similar subjects warning against the dangers of women painted by Cranach some of the earliest of which were commissioned for the bedchamber of prince Johann of Saxony in 1513. First published in 2003, the Colnaghi picture is a significant recent addition to the Cranach oeuvre. The Guardroom with Monkeys painted a century later by David Teniers II (Antwerp 1610-1690 Brussels) exposes another aspect of human folly: warfare. Monkeys wearing soldiers’ uniforms are grouped around tables, playing cards and back-gammon, one wearing a terracotta pot on his head, another a pewter funnel in place of a helmet, while on the right a cat has been taken prisoner and is escorted through the doorway by a group of monkey soldiers brandishing halberdiers. Despite the humour, there is a serious underlying message about the folly of war at a time when for most of the seventeenth century the Netherlands were occupied by troops. -

Frauke Josenhans, Vers Le Sud : Le Voyage De Johann Georg Von Dillis

RIHA Journal 0026 | 08 July 2011 Vers le Sud: Le voyage de Johann Georg von Dillis à travers la France, la Suisse et l'Italie en 18 !1 Frau"e Josenhans #eer revie$ and editing organized by: Institut national d'histoire de l'art (INHA), Paris 'evie$ers: Hu ertus !ohle, Julie Ra"os (&stract Southern France, and Provence in particular, started to lure painters as early as in the 18th century, first and foremost French ones, and then increasingly foreign painters, notably the German landscapist Johann Georg von Dillis. In 18!", he undertoo# a $ourney in the South of France in the company of the %avarian cro&n prince, the future 'ud&ig I. Dillis' $ourney is #no&n from t&o different sources: a group of dra&ings #no&n as the Voyage pittoresque dans le Midi de la France dessiné par Dillis *Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, +unich, and his unpublished correspondence &ith his brother Ignaz Dillis. .he dra&ings, &hich &ere ordered by the prince as a visual souvenir of his tour, reflect 'ud&ig(s interest in /oman 0nti1uity and thus include numerous vie&s of ancient monuments, such as the Maison Carrée in 23mes, the arc de triomphe in 4range and the ruins in Saint5/6my5de5Provence. 0part from this group there is another body of dra&ings, &hich Dillis also made during the $ourney, but that he chose not to include in the Voyage pittoresque. .hese sheets attest to the draughtsman(s attentiveness and sensibility for nature more obviously than the commissioned dra&ings. 0n official commission, the Voyage pittoresque is an e7ceptional artistic testimony of travel in the early 18th century. -

Die Münchner Akademie Der Bildenden Künste Vor 1808 Inhalt

Monika Meine-Schawe "... alles zu leisten, was man in Kunstsachen nur verlangen kan" Die Münchner Akademie der bildenden Künste vor 1808 Inhalt Die Forschung | Die Bittschrift | Die "Zeichnungs Schule respective Ma- ler= und Bildhauer academie" | Die Abgusssamlung der frühen Jahre | Der Umzug 1783/84 | Kopieren in der Galerie | Stipendien, Ausstellungen und Wettbewerbe | Die Professoren bis um 1800 | Die Abgusssammlung bis 1808 | Reformbestrebungen | Das Jahr 1808 | ANHANG 1 Die Bittschrift | ANHANG 2 Schülerliste | ANHANG 3 Gipsabgusssammlung | Verzeich- nis der abgekürzt zitierten Literatur | Abkürzungen | Abbildungen Erstpublikation in: Oberbayerisches Archiv, Bd. 128 (2004), S. 125-181. Die Forschung Die Münchner Akademie der bildenden Künste gilt als späte Gründung unter den deutschen Akademien1. Nur die 1808 ins Leben gerufene Institution hat ih- ren Platz im Bewusstsein der Öffentlichkeit (Abb. 1). Es ist die Akademie Jo- hann Peter von Langers (1756-1824, geadelt 1808) und Peter von Cornelius' (1783-1867). Zahlreiche Künstlergrößen gingen daraus hervor, die die süddeut- sche Kunstlandschaft des 19. Jahrhunderts nachhaltig prägten. Doch hatte diese Einrichtung ihre Vorgeschichte, die weit in das 18. Jahrhundert, noch vor die 1770 durch Kurfürst Maximilian III. Joseph (reg. 1745-1777) gegründete soge- nannte "Zeichnungsschule" zurückreicht, die die Bezeichnung "Akademie" be- reits im Namen trug ("Zeichnungs Schule respective Maler= und Bildhauer aca- demie"). Die Geschichte dieser älteren Institution ist, anders als die der spä- teren, nur unzureichend erforscht. Dies liegt einerseits sicherlich an der schwer zu überblickenden und lückenhaften dokumentarischen Überlieferung. Andererseits hat der lange Schatten der Akademie des 19. Jahrhunderts das Seinige dazu beigetragen, dass die Vorgängerin kaum zur Kenntnis genommen, 1 Zur Geschichte der Akademien siehe Pevsner 1986, hier S. -

RAPHAEL VRBINAS 1520 – 2020 (Intro) Raphael Celebrated The

RAPHAEL VRBINAS 1520 – 2020 (Intro) Raphael celebrated the greatest success with his art in Rome where he died 500 years ago. The many panel paintings and wall frescoes that he managed to complete there in little more than a decade have secured his international fame to this day – especially the painting of the so-called Stanze in the Vatican Palace and large altar paintings such as the Sistine Madonna. Raffaelo Sanzio, who was born in 1483, started his career, however, in Umbria and Tuscany. It is uncertain whether he completed his apprenticeship in the workshop of his father, who worked as a painter in Urbino, or under PIETRO PERUGINO in Perugia. He doubtlessly showed exceptional technical skill as a painter at an early age and ambitiously modelled his works on those of prominent colleagues such as Perugino, Pinturicchio and Signorelli. Between 1504 and 1508 Raphael remained mostly in Florence and explored Leonardo da Vinci’s and Michelangelo’s spectacular creations in his compositions. He also used his sound knowledge of FRA BARTOLOMMEO’s works equally masterfully for his own pictorial inventions. In this way he upheld his position among Florentine painters and attracted significant commissions for private devotional paintings, several portraits and an altar painting. This exhibition is devoted to Raphael’s depiction of the Holy Family commissioned by a Florentine merchant. As the painter of pictures of sublime beauty Raphael attained cult status in the 19th century, in particular. Ludwig I of Bavaria and his gallery director, Johann Georg von Dillis, revered him as the ‘king of painting’. The 500th anniversary of Raphael’s death provides an occasion to recall the history of his fame and to reflect on the extent his works influenced the pictorial language of the western world in the modern period. -

Olevano, Die Erste Künstlerkolonie Europas

„Es ist, als wenn mit der weichen, ermattenden und doch erfrischenden Luft Italiens eine andere Seele ein zöge, als wenn mein inneres Gemüt auch einen ewigen Frühling hervortriebe, wie er von außen um mich glänzt und schwillt und sich treibend blüht. Der Himmel hier ist fast immer heiter, alle Wolken ziehn nach Norden, so auch Olevano, die Sorgen […] In Italien ist es, wo die Wollust die Vögel zum Singen an treibt, wo jeder kühle Baumschatten Liebe die erste Künstlerkolonie duftet, wo es dem Bache in den Mund gelegt ist, von Wonne zu rieseln und zu scherzen.“ Europas Ludwig Tieck (Franz Sternbalds Wanderungen, 1798) 1 „Viele Örter auf den sonnigen Höhen angela windholz oder in den dunklen Falten der Ge - birge; Burgen, Klöster und Städte wie spielend in die Luft gehoben. Eine epische Ruhe überall. Die Linien dieser Gebirge am reinsten Blau des Him mels sind so scharf und klar, daß sie das Auge bezaubern; man möchte hinü ber, auf den leuchtenden Kanten und Flächen in der Frische jener hohen 95 Himmelszone einherzuschreiten. Über andern; auch das Kastell Pagliano [sic!] entdeckungslustiger Künstler zu einem der den Senkungen der Serra hebt sich hie ist schon erblaßt; aber hinter ihm flim - beliebtesten Reiseziele der Landschaftsmaler und da ein beschneites, sanft violen - mert die Abendsonne noch in den ganz Europas. Auf unzähligen Leinwänden farbenes Berghaupt aus der Wildnis Fenstern einer dunklen Stadt, die in wurden die Städtchen, ihre Aussichten, die der Abruzzen, noch eine andere Ferne meilenweiter Ferne auf einem Hügel Baum-, Fels- -

Daxer & M Arschall 20 17

XXIV Daxer & Marschall 2017 Recent Acquisitions, Catalogue XXIV, 2017 Barer Strasse 44 | 80799 Munich | Germany Tel. +49 89 28 06 40 | Fax +49 89 28 17 57 | Mob. +49 172 890 86 40 [email protected] | www.daxermarschall.com 2 Paintings, Oil Sketches and Sculpture, 1760-1940 My special thanks go to Simone Brenner and Diek Groenewald for their research and their work on the text. I am also grateful to them for so expertly supervising the production of the catalogue. We are much indebted to all those whose scholarship and expertise have helped in the preparation of this catalogue. In particular, our thanks go to: Paolo Antonacci, Helmut Börsch-Supan, Thomas le Claire, Sue Cubitt, Eveline Deneer, Roland Dorn, Christine Farese Sperken, Stefan Hammenbeck, Kilian Heck, Gerhard Kehlenbeck, Rupert Keim, Cathrin Klingsöhr-Leroy, Isabel von Klitzing, Anna-Carola Krausse, Marit Lange, Bjørn Li, Philip Mansmann, Verena Marschall, Sascha Mehringer, Werner Murrer, Hans-Joachim Neidhardt, Max Pinnau, Klaus Rohrandt, Annegret Schmidt-Philipps, Anastasiya Shtemenko, Gerd Spitzer, Talabardon & Gautier, Niels Vodder, Vanessa Voigt, Diane Webb, Gregor J. M. Weber, Wolf Zech. Our latest catalogue Oil Sketches, Paintings and Unser diesjähriger Katalog Oil Sketches, Paintings and Sculpture, 2017 Sculpture, 2017 comes to you in good time for this erreicht Sie pünktlich zum Kunstmarktereignis des Jahres, TEFAF, The year’s TEFAF, The European Fine Art Fair in Maas- European Fine Art Fair, Maastricht, 9. - 19. März 2017. tricht. TEFAF is the international art market high point of the year. It runs from 9 to 19 March 2017. Der Katalog präsentiert Werke, die unseren qualitativen und ästhetischen Maßstäben gerecht werden. -

Alte Pinakothek Press Information Raphael 1520–2020 Collection Presentation to Mark the 500Th Anniversary of Raphael's Death

ALTE PINAKOTHEK PRESS INFORMATION RAPHAEL 1520–2020 COLLECTION PRESENTATION TO MARK THE 500TH ANNIVERSARY OF RAPHAEL’S DEATH IN THE FLORENTINE ROOM, 1ST FLOOR, ROOM IV ALTE PINAKOTHEK Raphael celebrated the greatest success with his art in Rome where he died 500 years ago. The many panel paintings and wall frescoes that he managed to complete there in little more than a decade have secured his international fame to this day. As the painter of pictures of sublime beauty Raphael attained cult status in the 19th century, in particular. Ludwig I of Bavaria and his gallery director, Johann Georg von Dillis, revered him as the ‘king of painting’. The 500th anniversary of Raphael’s death provides an occasion to recall the history of his fame and to reflect on the extent his works influenced the pictorial language of the western world in the modern period. For this reason, an early, major work by the great master, the so-called Canigiani Holy Family, forms the focal point of the Florentine Room at the Alte Pinakothek, the foundation stone of which was laid in 1826 on Raphael’s birthday. This focussed collection presentation with five works from the Alte Pinakothek, including two devotional pictures by Raphael, places the Canigiani Holy Family in dialogue with a painting by Friedrich Overbeck from the Neue Pinakothek and a loan from the Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung – a porcelain picture by Christian Adler. Together with an altar painting by Pietro Perugino and a work by Fra Bartolommeo the selection draws attention to the fact that the career of the artist, born Raffaelo Sanzio in Urbino in 1483, had its beginnings in Umbria and Tuscany. -

Page, Canvas, Wall: Visualising the History of Art

Issue No. 4/2020 Page, Canvas, Wall: Visualising the History of Art Michaela Giebelhausen, PhD, Course Leader, BA Culture, Criticism and Curation, Central St Martins, University of the Arts, London Also published in Susanna Pettersson (ed.), Inspiration – Iconic Works. Ateneum Publications Vol. 132. Helsinki: Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum, 2020, 31–45 In 1909, the Italian poet and founder of the Futurist movement, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti famously declared, ‘[w]e will destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind’.1 He compared museums to cemeteries, ‘[i]dentical, surely, in the sinister promiscuity of so many bodies unknown to one another… where one lies forever beside hated or unknown beings’. This comparison of the museum with the cemetery has often been cited as an indication of the Futurists’ radical rejection of traditional institutions. It certainly made these institutions look dead. With habitual hyperbole Marinetti claimed: ‘We stand on the last promontory of the centuries!… Why should we look back […]? Time and Space died yesterday.’ The brutal breathlessness of Futurist thinking rejected all notions of a history of art. This essay considers how the history of art, embodied in art-historical canons, schools, periods, and aesthetic standards, has been conceptualised through writing, the organisation of collections, and the decoration of new museum buildings. It examines some of the moments in which the page, the canvas and the wall offer seminal and selective visualisations of the history of art and deploy notions of time and space that are complex and contradictory, and far from dead. Writing the history of art The history of art began as a history of artists.