Page, Canvas, Wall: Visualising the History of Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Press Release

Press Contacts Patrick Milliman 212.590.0310, [email protected] Alanna Schindewolf 212.590.0311, [email protected] THE MORGAN HOSTS MAJOR EXHIBITION OF MASTER DRAWINGS FROM MUNICH’S FAMED STAATLICHE GRAPHISCHE SAMMLUNG SHOW INCLUDES WORKS FROM THE RENAISSANCE TO THE MODERN PERIOD AND MARKS THE FIRST TIME THE GRAPHISCHE SAMMLUNG HAS LENT SUCH AN IMPORTANT GROUP OF DRAWINGS TO AN AMERICAN MUSEUM Dürer to de Kooning: 100 Master Drawings from Munich October 12, 2012–January 6, 2013 **Press Preview: Thursday, October 11, 10 a.m. until 11:30 a.m.** RSVP: (212) 590-0393, [email protected] New York, NY, August 25, 2012—This fall, The Morgan Library & Museum will host an extraordinary exhibition of rarely- seen master drawings from the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich, one of Europe’s most distinguished drawings collections. On view October 12, 2012– January 6, 2013, Dürer to de Kooning: 100 Master Drawings from Munich marks the first time such a comprehensive and prestigious selection of works has been lent to a single exhibition. Johann Friedrich Overbeck (1789–1869) Italia and Germania, 1815–28 Dürer to de Kooning was conceived in Inv. 2001:12 Z © Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München exchange for a show of one hundred drawings that the Morgan sent to Munich in celebration of the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung’s 250th anniversary in 2008. The Morgan’s organizing curators were granted unprecedented access to the Graphische Sammlung’s vast holdings, ultimately choosing one hundred masterworks that represent the breadth, depth, and vitality of the collection. The exhibition includes drawings by Italian, German, French, Dutch, and Flemish artists of the Renaissance and baroque periods; German draftsmen of the nineteenth century; and an international contingent of modern and contemporary draftsmen. -

Oil Sketches and Paintings 1660 - 1930 Recent Acquisitions

Oil Sketches and Paintings 1660 - 1930 Recent Acquisitions 2013 Kunsthandel Barer Strasse 44 - D-80799 Munich - Germany Tel. +49 89 28 06 40 - Fax +49 89 28 17 57 - Mobile +49 172 890 86 40 [email protected] - www.daxermarschall.com My special thanks go to Sabine Ratzenberger, Simone Brenner and Diek Groenewald, for their research and their work on the text. I am also grateful to them for so expertly supervising the production of the catalogue. We are much indebted to all those whose scholarship and expertise have helped in the preparation of this catalogue. In particular, our thanks go to: Sandrine Balan, Alexandra Bouillot-Chartier, Corinne Chorier, Sue Cubitt, Roland Dorn, Jürgen Ecker, Jean-Jacques Fernier, Matthias Fischer, Silke Francksen-Mansfeld, Claus Grimm, Jean- François Heim, Sigmar Holsten, Saskia Hüneke, Mathias Ary Jan, Gerhard Kehlenbeck, Michael Koch, Wolfgang Krug, Marit Lange, Thomas le Claire, Angelika and Bruce Livie, Mechthild Lucke, Verena Marschall, Wolfram Morath-Vogel, Claudia Nordhoff, Elisabeth Nüdling, Johan Olssen, Max Pinnau, Herbert Rott, John Schlichte Bergen, Eva Schmidbauer, Gerd Spitzer, Andreas Stolzenburg, Jesper Svenningsen, Rudolf Theilmann, Wolf Zech. his catalogue, Oil Sketches and Paintings nser diesjähriger Katalog 'Oil Sketches and Paintings 2013' erreicht T2013, will be with you in time for TEFAF, USie pünktlich zur TEFAF, the European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht, the European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht. 14. - 24. März 2013. TEFAF runs from 14-24 March 2013. Die in dem Katalog veröffentlichten Gemälde geben Ihnen einen The selection of paintings in this catalogue is Einblick in das aktuelle Angebot der Galerie. Ohne ein reiches Netzwerk an designed to provide insights into the current Beziehungen zu Sammlern, Wissenschaftlern, Museen, Kollegen, Käufern und focus of the gallery’s activities. -

Page, Canvas, Wall: Visualising the History Of

Title Page, Canvas, Wall: Visualising the History of Art Type Article URL https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/15882/ Dat e 2 0 2 0 Citation Giebelhausen, Michaela (2020) Page, Canvas, Wall: Visualising the History of Art. FNG Research (4/2020). pp. 1-14. ISSN 2343-0850 Cr e a to rs Giebelhausen, Michaela Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected] . License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author Issue No. 4/2020 Page, Canvas, Wall: Visualising the History of Art Michaela Giebelhausen, PhD, Course Leader, BA Culture, Criticism and Curation, Central St Martins, University of the Arts, London Also published in Susanna Pettersson (ed.), Inspiration – Iconic Works. Ateneum Publications Vol. 132. Helsinki: Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum, 2020, 31–45 In 1909, the Italian poet and founder of the Futurist movement, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti famously declared, ‘[w]e will destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind’.1 He compared museums to cemeteries, ‘[i]dentical, surely, in the sinister promiscuity of so many bodies unknown to one another… where one lies forever beside hated or unknown beings’. This comparison of the museum with the cemetery has often been cited as an indication of the Futurists’ radical rejection of traditional institutions. It certainly made these institutions look dead. With habitual hyperbole Marinetti claimed: ‘We stand on the last promontory of the centuries!… Why should we look back […]? Time and Space died yesterday.’ The brutal breathlessness of Futurist thinking rejected all notions of a history of art. -

Center 5 Research Reports and Record of Activities

National Gallery of Art Center 5 Research Reports and Record of Activities ~ .~ I1{, ~ -1~, dr \ --"-x r-i>- : ........ :i ' i 1 ~,1": "~ .-~ National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Center 5 Research Reports and Record of Activities June 1984---May 1985 Washington, 1985 National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Washington, D.C. 20565 Telephone: (202) 842-6480 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without thc written permission of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20565. Copyright © 1985 Trustees of the National Gallery of Art, Washington. This publication was produced by the Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, Washington. Frontispiece: Gavarni, "Les Artistes," no. 2 (printed by Aubert et Cie.), published in Le Charivari, 24 May 1838. "Vois-tu camarade. Voil~ comme tu trouveras toujours les vrais Artistes... se partageant tout." CONTENTS General Information Fields of Inquiry 9 Fellowship Program 10 Facilities 13 Program of Meetings 13 Publication Program 13 Research Programs 14 Board of Advisors and Selection Committee 14 Report on the Academic Year 1984-1985 (June 1984-May 1985) Board of Advisors 16 Staff 16 Architectural Drawings Advisory Group 16 Members 16 Meetings 21 Members' Research Reports Reports 32 i !~t IJ ii~ . ~ ~ ~ i.~,~ ~ - ~'~,i'~,~ ii~ ~,i~i!~-i~ ~'~'S~.~~. ,~," ~'~ i , \ HE CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS was founded T in 1979, as part of the National Gallery of Art, to promote the study of history, theory, and criticism of art, architecture, and urbanism through the formation of a community of scholars. -

Winckelmann, Greek Masterpieces, and Architectural Sculpture

Winckelmann, Greek masterpieces, and architectural sculpture. Prolegomena to a history of classical archaeology in museums Book or Report Section Accepted Version Smith, A. C. (2017) Winckelmann, Greek masterpieces, and architectural sculpture. Prolegomena to a history of classical archaeology in museums. In: Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. (eds.) The Diversity of Classical Archaeology. Studies in Classical Archaeology, 1. Brepols. ISBN 9782503574936 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/70169/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: http://www.brepols.net/Pages/ShowProduct.aspx?prod_id=IS-9782503574936-1 Publisher: Brepols All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Winckelmann, Greek Masterpieces, and Architectural Sculpture Prolegomena to a History of Classical Archaeology in Museums∗ Amy C. Smith ‘Much that we might imagine as ideal was natural for them [the ancient Greeks].’1 ♣ Just as Johann Joachim Winckelmann mourned the loss of antiquity, so have subsequent generations mourned his passing at the age of fifty, in 1768, as he was planning his first journey to Greece. His deification through — not least — the placement of his profile head, as if carved out of a gemstone, on the title page of the first volume of his Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums (‘History of Ancient Art’) in 1776 (the second edition, published posthumously) made him the poster boy for the study of classical art history and its related branches, Altertumswissenschaft or classical studies, history of art, and classical 2 archaeology. -

Francia. Band 44

Francia. Forschungen zur Westeuropäischen Geschichte. Herausgegeben vom Deutschen Historischen Institut Paris (Institut historique allemand) Band 44 (2017) »L’Éloge de la folie«, version trilingue DOI: 10.11588/fr.2017.0.69017 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. François Labbé »L’ÉLOGE DE LA FOLIE«, VERSION TRILINGUE Publié par Jean-Jacques Thurneisen, avec Jean-Charles Laveaux pour traducteur de la version française Jean-Charles Laveaux (1749–1829) est peu connu et rarement cité. Quand on le fait, c’est prin- cipalement en raison de son activité de dictionnariste pendant le dernier quart de sa vie, quand il réussit à publier un »Dictionnaire de la langue française« (1802) bien supérieur à celui que l’Institut avait fait péniblement paraître peu avant. Pourtant, vingt-cinq ans plus tôt, il entamait une extraordinaire carrière littéraire à Bâle, carrière qui devait l’emmener à Berlin (où il sera »Professeur royal«), Stuttgart (Professeur au Carolinum) puis Strasbourg (âme des jacobins et directeur du »Courrier de Strasbourg«) et Paris (Directeur du »Journal de la Montagne«, édi- teur, imprimeur, historien, …)1. Né à Troyes dans une famille de la petite bourgeoisie de la ville, après des études chez les ora- toriens, il entre dans les ordres, devient professeur de théologie, enseigne à Paris mais doit quit- ter cette ville pour de probables raisons de cœur. -

Eine Aktuelle Sicht Auf Die 16000 Landkarten Des Johann Friedrich Von Ryhiner (1732–1803)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bern Open Repository and Information System (BORIS) 1 Thomas Klöti: Legenden zur Ausstellung der Weltensammler – eine aktuelle Sicht auf die 16000 Landkarten des Johann Friedrich von Ryhiner (1732–1803). Sonderausstellung vom 10. September bis 6. Dezember 1998 im Schweizerischen Alpinen Museum in Bern 1.1.1 Sammelband mit Titelblättern: Titelblatt des 3. Teils des 6- bändigen «Novus Atlas» aus dem Landkartenverlag Blaeu, 1642–1656 Das Titelblatt zeigt die Geographen Claudius Ptolemäus (mit Armillarsphäre und Zirkel) sowie Marinus von Tyrus (mit Karte). In der Renaissance wurde die «Geographie» von Ptolemäus wiederentdeckt: Der darin enthaltene Grundstock an antiken Karten wurde anschliessend immer mehr mit modernen Karten erweitert. Das 17. Jahrhundert gilt als das Jahrhundert der grossen und prachtvoll ausgestatteten Atlanten. (Bern, Sammlung Ryhiner) Recueil factice formé des pages de titre de la Collection Ryhiner: Page de titre du tome III du «Novus Atlas» – un ouvrage en 6 tomes, paru aux éditions cartographiques Blaeu, entre 1642 et 1656 La page de titre représente deux personnages de l’antiquité, les géographes Claude Ptolémée portant la sphère armillaire et le compas, et Marin de Tyr, une carte à la main. La «Géographie» de Ptolémée a été redécouverte au cours de la Renaissance: Le fonds de cartes provenant effectivement de l’antiquité a été successivement élargi par des cartes plus récentes de provenance diverse. Le XVIIe siècle est l’âge d’or des atlas monumentaux, présentés sous des décors somptueux. | downloaded: 13.3.2017 (Berne, Collection Ryhiner) 1.1.2 Stehpult mit Manuskript, Tintenfass und Federkiel Das zweibändige Manuskript «Geographische Nachrichten» enthält von Ryhiners allgemeine Erd- und Kartenkunde. -

Dokumentvorlage

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Classification as a principle: the transformation of the Vienna K.K. Bildergalerie into a 'visible history of art' (1772-1787) Meijers, D.J. Publication date 2011 Document Version Submitted manuscript Published in Kunst als Kulturgut. - Bd. 2: "Kunst" und "Staat" Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Meijers, D. J. (2011). Classification as a principle: the transformation of the Vienna K.K. Bildergalerie into a 'visible history of art' (1772-1787). In E. Weisser-Lohmann (Ed.), Kunst als Kulturgut. - Bd. 2: "Kunst" und "Staat" (pp. 161-180). (Neuzeit und Gegenwart). Fink. http://www.fernuni-hagen.de/KSW/opencontent/musealisierung/pdf/Meijers_Classification.pdf General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 DEBORA J. -

Winckelmann Und Die Schweiz Internationales Kolloquium in Zürich, 18

Winckelmann und die Schweiz Internationales Kolloquium in Zürich, 18. und 19. Mai 2017 Schweizerisches Institut für Kunstwissenschaft (SIK-ISEA) Zollikerstrasse 32 (Nähe Kreuzplatz), CH-8032 Zürich T +41 44 388 51 51 / F +41 44 381 52 50, [email protected], www.sik-isea.ch Konzept und Organisation SIK-ISEA, Zürich Dr. Matthias Oberli lic. phil. Regula Krähenbühl Winckelmann-Gesellschaft, Stendal Prof. Dr. Max Kunze Dr. Adelheid Müller Kunsthistorisches Seminar der Universität Basel Prof. Dr. Andreas Beyer Finanzielle Unterstützung leisten Frey-Clavel-Stiftung, Basel Schweizerische Akademie der Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaften (SAGW) Winckelmann-Gesellschaft, Stendal Winckelmann-Ausstellung in der Bibliothek Werner Oechslin Luegeten 11, CH-8840 Einsiedeln In der Bibliothek Werner Oechslin wird am 20. Mai 2017 eine Ausstellung zu Winckelmann eröffnet, die in rund 100 Exponaten dessen Entwicklung vom Bibliothekar zur Gründerfigur der deutschen Kunstwissenschaft herausstellt. In besonderer Weise thematisiert wird dabei der Kontrast zwischen der Figur des Antiquars, der sich gemäss Caylus der «Physique» der Kunstgegenstände bis in alle Verästelungen hinein widmen soll, und dem nach Höherem strebenden, idealisch denkenden Winckelmann; darauf beziehen sich sowohl die Vorstellung des Klassischen wie ein ethisch begründeter Schönheitsbegriff mit Wirkungen bis in unsere Zeit. Die Ausstellung dauert bis Ende 2017; für Öffnungszeiten, Führungen, Adressen: [email protected]; http://www.bibliothek-oechslin.ch 1 Donnerstag, 18. Mai -

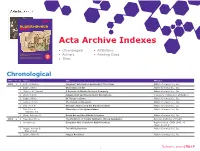

Acta Archive Indexes Directory

VOLUME 50, NO. 1 | 2017 ALDRICHIMICA ACTA Acta Archive Indexes • Chronological • Affiliations 4-Substituted Prolines: Useful Reagents in Enantioselective HIMICA IC R A Synthesis and Conformational Restraints in the Design of D C L T Bioactive Peptidomimetics A A • Authors • Painting Clues Recent Advances in Alkene Metathesis for Natural Product Synthesis—Striking Achievements Resulting from Increased 1 7 9 1 Sophistication in Catalyst Design and Synthesis Strategy 68 20 • Titles The life science business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany operates as MilliporeSigma in the U.S. and Canada. Chronological YEAR Vol. No. Authors Title Affiliation 1968 1 1 Buth, William F. Fragment Information Retrieval of Structures Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 1 Bader, Alfred Chemistry and Art Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 1 Higbee, W. Edward A Portrait of Aldrich Chemical Company Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 2 West, Robert Squaric Acid and the Aromatic Oxocarbons University of Wisconsin at Madison 2 Bader, Alfred Of Things to Come Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 3 Koppel, Henry The Compleat Chemists Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 3 Biel, John H. Biogenic Amines and the Emotional State Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 4 Biel, John H. Chemistry of the Quinuclidines Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. Warawa, E.J. 4 Clark, Anthony M. Dutch Art and the Aldrich Collection Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 1969 2 1 May, Everette L. The Evolution of Totally Synthetic, Strong Analgesics National Institutes of Health 1 Anonymous Computer Aids Search for R&D Chemicals Reprinted from C&EN 1968, 46 (Sept. 2), 26-27 2 Hopps, Harvey B. The Wittig Reaction Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. Biel, John H. -

Bernheimer – Colnaghi Announce Their Collection Being Exhibited at TEFAF, Maastricht, 7 – 16 March 2008. Submitted By: Cassleton Elliott Thursday, 14 February 2008

Bernheimer – Colnaghi announce their collection being exhibited at TEFAF, Maastricht, 7 – 16 March 2008. Submitted by: Cassleton Elliott Thursday, 14 February 2008 Among the highlights of the Bernheimer-Colnaghi stand at TEFAF, Maastricht, is Lucas Cranach the Elder’s Aristotle and Phyllis. The humiliation of the Greek philosopher Aristotle was one of the most powerful and popular pictorial examples of the theme of Weibermacht or the ‘Power of Women’. Aristotle is said to have admonished one of his students (traditionally identified as Alexander the Great) for paying too much attention to Phyllis, a woman of the court. She got her revenge by seducing the philosopher and persuading him to allow her to ride on his back in return for the promise of sexual favours. The picture can be linked to a group of paintings of similar subjects warning against the dangers of women painted by Cranach some of the earliest of which were commissioned for the bedchamber of prince Johann of Saxony in 1513. First published in 2003, the Colnaghi picture is a significant recent addition to the Cranach oeuvre. The Guardroom with Monkeys painted a century later by David Teniers II (Antwerp 1610-1690 Brussels) exposes another aspect of human folly: warfare. Monkeys wearing soldiers’ uniforms are grouped around tables, playing cards and back-gammon, one wearing a terracotta pot on his head, another a pewter funnel in place of a helmet, while on the right a cat has been taken prisoner and is escorted through the doorway by a group of monkey soldiers brandishing halberdiers. Despite the humour, there is a serious underlying message about the folly of war at a time when for most of the seventeenth century the Netherlands were occupied by troops. -

Die Kaiserliche Gemäldegalerie in Wien Und Die Anfänge Des Öffentlichen Kunstmuseums

GUDRUN SWOBODA (HG.) Die kaiserliche Gemäldegalerie in Wien und die Anfänge des öffentlichen Kunstmuseums BAND II EUROPÄISChe MUSEUMSKULTUREN UM 1800 Die kaiserliche Gemäldegalerie in Wien und die Anfänge des öffentlichen Kunstmuseums 2013 BÖHLAU VERLAG WIEN KÖLN WEIMAR GUDRUN SWOBODA (HG.) Die kaiserliche Gemäldegalerie in Wien und die Anfänge des öffentlichen Kunstmuseums BAND 2 EUROPÄISCHE MUSEUMSKULTUREN UM 1800 2013 BÖHLAU VERLAG WIEN KÖLN WEIMAR IMPRESSUM Gudrun Swoboda (Hg.) Die kaiserliche Gemäldegalerie in Wien und die Anfänge des öffentlichen Kunstmuseums Band 1 Die kaiserliche Galerie im Wiener Belvedere (1776–1837) Band 2 Europäische Museumskulturen um 1800 Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Wien 2013 Redaktion Gudrun Swoboda, Kristine Patz, Nora Fischer Lektorat Karin Zeleny Art-Direktion Stefan Zeisler Graphische Gestaltung Johanna Kopp, Maria Theurl Covergestaltung Brigitte Simma Bildbearbeitung Tom Ritter, Michael Eder, Sanela Antic Hervorgegangen aus einem Projekt des Förderprogramms forMuse, gefördert vom Bundesministerium für Wissenschaft und Forschung Veröffentlicht mit Unterstützung des Austrian Science Fund (FWF): PUB 121-V21/PUB 122-V21 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://portal.dnb.de abrufbar. Abbildungen auf der Eingangsseite Bernardo Bellotto, Wien, vom Belvedere aus gesehen. Öl auf Leinwand, um 1758/61. Wien, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie Inv.-Nr. 1669, Detail Druck und Bindung: Holzhausen Druck Gmbh, Wien Gedruckt auf chlor- und säurefreiem Papier Printed in Austria ISBN 978-3-205-79534-6 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist unzulässig. © 2013 Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien – www.khm.at © 2013 by Böhlau Verlag Ges.m.b.H.