Dokumentvorlage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Center 5 Research Reports and Record of Activities

National Gallery of Art Center 5 Research Reports and Record of Activities ~ .~ I1{, ~ -1~, dr \ --"-x r-i>- : ........ :i ' i 1 ~,1": "~ .-~ National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Center 5 Research Reports and Record of Activities June 1984---May 1985 Washington, 1985 National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Washington, D.C. 20565 Telephone: (202) 842-6480 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without thc written permission of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20565. Copyright © 1985 Trustees of the National Gallery of Art, Washington. This publication was produced by the Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, Washington. Frontispiece: Gavarni, "Les Artistes," no. 2 (printed by Aubert et Cie.), published in Le Charivari, 24 May 1838. "Vois-tu camarade. Voil~ comme tu trouveras toujours les vrais Artistes... se partageant tout." CONTENTS General Information Fields of Inquiry 9 Fellowship Program 10 Facilities 13 Program of Meetings 13 Publication Program 13 Research Programs 14 Board of Advisors and Selection Committee 14 Report on the Academic Year 1984-1985 (June 1984-May 1985) Board of Advisors 16 Staff 16 Architectural Drawings Advisory Group 16 Members 16 Meetings 21 Members' Research Reports Reports 32 i !~t IJ ii~ . ~ ~ ~ i.~,~ ~ - ~'~,i'~,~ ii~ ~,i~i!~-i~ ~'~'S~.~~. ,~," ~'~ i , \ HE CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS was founded T in 1979, as part of the National Gallery of Art, to promote the study of history, theory, and criticism of art, architecture, and urbanism through the formation of a community of scholars. -

Winckelmann, Greek Masterpieces, and Architectural Sculpture

Winckelmann, Greek masterpieces, and architectural sculpture. Prolegomena to a history of classical archaeology in museums Book or Report Section Accepted Version Smith, A. C. (2017) Winckelmann, Greek masterpieces, and architectural sculpture. Prolegomena to a history of classical archaeology in museums. In: Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. (eds.) The Diversity of Classical Archaeology. Studies in Classical Archaeology, 1. Brepols. ISBN 9782503574936 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/70169/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: http://www.brepols.net/Pages/ShowProduct.aspx?prod_id=IS-9782503574936-1 Publisher: Brepols All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Winckelmann, Greek Masterpieces, and Architectural Sculpture Prolegomena to a History of Classical Archaeology in Museums∗ Amy C. Smith ‘Much that we might imagine as ideal was natural for them [the ancient Greeks].’1 ♣ Just as Johann Joachim Winckelmann mourned the loss of antiquity, so have subsequent generations mourned his passing at the age of fifty, in 1768, as he was planning his first journey to Greece. His deification through — not least — the placement of his profile head, as if carved out of a gemstone, on the title page of the first volume of his Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums (‘History of Ancient Art’) in 1776 (the second edition, published posthumously) made him the poster boy for the study of classical art history and its related branches, Altertumswissenschaft or classical studies, history of art, and classical 2 archaeology. -

Francia. Band 44

Francia. Forschungen zur Westeuropäischen Geschichte. Herausgegeben vom Deutschen Historischen Institut Paris (Institut historique allemand) Band 44 (2017) »L’Éloge de la folie«, version trilingue DOI: 10.11588/fr.2017.0.69017 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. François Labbé »L’ÉLOGE DE LA FOLIE«, VERSION TRILINGUE Publié par Jean-Jacques Thurneisen, avec Jean-Charles Laveaux pour traducteur de la version française Jean-Charles Laveaux (1749–1829) est peu connu et rarement cité. Quand on le fait, c’est prin- cipalement en raison de son activité de dictionnariste pendant le dernier quart de sa vie, quand il réussit à publier un »Dictionnaire de la langue française« (1802) bien supérieur à celui que l’Institut avait fait péniblement paraître peu avant. Pourtant, vingt-cinq ans plus tôt, il entamait une extraordinaire carrière littéraire à Bâle, carrière qui devait l’emmener à Berlin (où il sera »Professeur royal«), Stuttgart (Professeur au Carolinum) puis Strasbourg (âme des jacobins et directeur du »Courrier de Strasbourg«) et Paris (Directeur du »Journal de la Montagne«, édi- teur, imprimeur, historien, …)1. Né à Troyes dans une famille de la petite bourgeoisie de la ville, après des études chez les ora- toriens, il entre dans les ordres, devient professeur de théologie, enseigne à Paris mais doit quit- ter cette ville pour de probables raisons de cœur. -

Eine Aktuelle Sicht Auf Die 16000 Landkarten Des Johann Friedrich Von Ryhiner (1732–1803)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bern Open Repository and Information System (BORIS) 1 Thomas Klöti: Legenden zur Ausstellung der Weltensammler – eine aktuelle Sicht auf die 16000 Landkarten des Johann Friedrich von Ryhiner (1732–1803). Sonderausstellung vom 10. September bis 6. Dezember 1998 im Schweizerischen Alpinen Museum in Bern 1.1.1 Sammelband mit Titelblättern: Titelblatt des 3. Teils des 6- bändigen «Novus Atlas» aus dem Landkartenverlag Blaeu, 1642–1656 Das Titelblatt zeigt die Geographen Claudius Ptolemäus (mit Armillarsphäre und Zirkel) sowie Marinus von Tyrus (mit Karte). In der Renaissance wurde die «Geographie» von Ptolemäus wiederentdeckt: Der darin enthaltene Grundstock an antiken Karten wurde anschliessend immer mehr mit modernen Karten erweitert. Das 17. Jahrhundert gilt als das Jahrhundert der grossen und prachtvoll ausgestatteten Atlanten. (Bern, Sammlung Ryhiner) Recueil factice formé des pages de titre de la Collection Ryhiner: Page de titre du tome III du «Novus Atlas» – un ouvrage en 6 tomes, paru aux éditions cartographiques Blaeu, entre 1642 et 1656 La page de titre représente deux personnages de l’antiquité, les géographes Claude Ptolémée portant la sphère armillaire et le compas, et Marin de Tyr, une carte à la main. La «Géographie» de Ptolémée a été redécouverte au cours de la Renaissance: Le fonds de cartes provenant effectivement de l’antiquité a été successivement élargi par des cartes plus récentes de provenance diverse. Le XVIIe siècle est l’âge d’or des atlas monumentaux, présentés sous des décors somptueux. | downloaded: 13.3.2017 (Berne, Collection Ryhiner) 1.1.2 Stehpult mit Manuskript, Tintenfass und Federkiel Das zweibändige Manuskript «Geographische Nachrichten» enthält von Ryhiners allgemeine Erd- und Kartenkunde. -

Winckelmann Und Die Schweiz Internationales Kolloquium in Zürich, 18

Winckelmann und die Schweiz Internationales Kolloquium in Zürich, 18. und 19. Mai 2017 Schweizerisches Institut für Kunstwissenschaft (SIK-ISEA) Zollikerstrasse 32 (Nähe Kreuzplatz), CH-8032 Zürich T +41 44 388 51 51 / F +41 44 381 52 50, [email protected], www.sik-isea.ch Konzept und Organisation SIK-ISEA, Zürich Dr. Matthias Oberli lic. phil. Regula Krähenbühl Winckelmann-Gesellschaft, Stendal Prof. Dr. Max Kunze Dr. Adelheid Müller Kunsthistorisches Seminar der Universität Basel Prof. Dr. Andreas Beyer Finanzielle Unterstützung leisten Frey-Clavel-Stiftung, Basel Schweizerische Akademie der Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaften (SAGW) Winckelmann-Gesellschaft, Stendal Winckelmann-Ausstellung in der Bibliothek Werner Oechslin Luegeten 11, CH-8840 Einsiedeln In der Bibliothek Werner Oechslin wird am 20. Mai 2017 eine Ausstellung zu Winckelmann eröffnet, die in rund 100 Exponaten dessen Entwicklung vom Bibliothekar zur Gründerfigur der deutschen Kunstwissenschaft herausstellt. In besonderer Weise thematisiert wird dabei der Kontrast zwischen der Figur des Antiquars, der sich gemäss Caylus der «Physique» der Kunstgegenstände bis in alle Verästelungen hinein widmen soll, und dem nach Höherem strebenden, idealisch denkenden Winckelmann; darauf beziehen sich sowohl die Vorstellung des Klassischen wie ein ethisch begründeter Schönheitsbegriff mit Wirkungen bis in unsere Zeit. Die Ausstellung dauert bis Ende 2017; für Öffnungszeiten, Führungen, Adressen: [email protected]; http://www.bibliothek-oechslin.ch 1 Donnerstag, 18. Mai -

Die Kaiserliche Gemäldegalerie in Wien Und Die Anfänge Des Öffentlichen Kunstmuseums

GUDRUN SWOBODA (HG.) Die kaiserliche Gemäldegalerie in Wien und die Anfänge des öffentlichen Kunstmuseums BAND II EUROPÄISChe MUSEUMSKULTUREN UM 1800 Die kaiserliche Gemäldegalerie in Wien und die Anfänge des öffentlichen Kunstmuseums 2013 BÖHLAU VERLAG WIEN KÖLN WEIMAR GUDRUN SWOBODA (HG.) Die kaiserliche Gemäldegalerie in Wien und die Anfänge des öffentlichen Kunstmuseums BAND 2 EUROPÄISCHE MUSEUMSKULTUREN UM 1800 2013 BÖHLAU VERLAG WIEN KÖLN WEIMAR IMPRESSUM Gudrun Swoboda (Hg.) Die kaiserliche Gemäldegalerie in Wien und die Anfänge des öffentlichen Kunstmuseums Band 1 Die kaiserliche Galerie im Wiener Belvedere (1776–1837) Band 2 Europäische Museumskulturen um 1800 Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Wien 2013 Redaktion Gudrun Swoboda, Kristine Patz, Nora Fischer Lektorat Karin Zeleny Art-Direktion Stefan Zeisler Graphische Gestaltung Johanna Kopp, Maria Theurl Covergestaltung Brigitte Simma Bildbearbeitung Tom Ritter, Michael Eder, Sanela Antic Hervorgegangen aus einem Projekt des Förderprogramms forMuse, gefördert vom Bundesministerium für Wissenschaft und Forschung Veröffentlicht mit Unterstützung des Austrian Science Fund (FWF): PUB 121-V21/PUB 122-V21 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://portal.dnb.de abrufbar. Abbildungen auf der Eingangsseite Bernardo Bellotto, Wien, vom Belvedere aus gesehen. Öl auf Leinwand, um 1758/61. Wien, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie Inv.-Nr. 1669, Detail Druck und Bindung: Holzhausen Druck Gmbh, Wien Gedruckt auf chlor- und säurefreiem Papier Printed in Austria ISBN 978-3-205-79534-6 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist unzulässig. © 2013 Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien – www.khm.at © 2013 by Böhlau Verlag Ges.m.b.H. -

1B.-Rynek-Sztuki... EN.Pdf

Konrad Niemira THE ART MARKET IN WARSAW DURING THE TIMES OF STanisłaW II AUGUST1 When reading publications devoted to artistic culture in eighteenth-century Warsaw, one may sometimes get the impression that the art market in this city was rather ‘backward’ and ‘underdeveloped’.2 This dark legend was originated, or at least codified, by a pioneering researcher on the subject, the outstanding art historian Andrzej Ryszkiewicz. Ryszkiewicz devotes some room to the period in question in the first chapter of his monograph on the paintings trade in nine- teenth-century Warsaw. According to this scholar, there were only two shops that offered paintings for sale at the end of the eighteenth century: Ernst Christopher Bormann’s and Karol Hampel’s, although it must be stressed that neither mer- 1 This article could not have been written without the support of Prof. Andrzej Pieńkos and Piotr Skowroński, who invited me to take part in the academic seminar of the Ośrodek Badań nad Epoką Stanisławowską in 2017. I am grateful to both of them. Further work on the text as well as additional archival research would not have been possible without a scholarship from the Burlington Magazine, whose Council I would also like to thank here. 2 A. Ryszkiewicz, Początki handlu obrazami w środowisku warszawskim, Wrocław 1953; A. Magier, Este- tyka miasta stołecznego Warszawy, Warszawa 1963, p. 280, footnote 1; J. Białostocki, M. Walicki, Ma- larstwo europejskie w zbiorach polskich, Warszawa 1958, p. 23; S. Bołdok, Antykwariaty artystyczne, salony i domy aukcyjne, Warszawa, 2004 pp. 17–27; T. de Rosset describes the Warsaw paintings market as ‘miserable’, dominated by itinerant picturists of second-rate quality. -

De Silvestre, Ritratto Di Augusto Il Forte (1670-1733) S.D

Antoine Pesne, Ritratto di Federico Giglielmo I 1733 Berlino, Deutsche Historisches Museum Il cosiddetto “Re soldato” regnò 1713-1740 De Silvestre, Ritratto di Augusto il Forte (1670-1733) s.d. Dresda, Galerie Alte Meister Il principe elettore di Sassonia nel 1696 divenne Augusto II re di Polonia I “Lange Kerls” di Federico Giglielmo I SOTTO: Dresda, la collezione di porcellana allo Zwinger (Bogengalerie) Antoine Pesne, Ritratto di Federico II e di sua sorella Guglielmina, 1720 u SOTTO: Autoritratto di Federico Guglielmo I, s.d. Il «re soldato» a un suo agente attivo sul mercato d’arte de L’Aia (s.d.): • «… pezzi di scuola olandese, anche quelli che abbiano un che di speculativo, ma nessun pezzo italiano. […] I pezzi che comprerete per me devono essere davvero buoni, ma non i più preziosi e costosi, ché io preferisco possedere molti buoni pezzi che pochi pezzi e molto cari». Federico II o Federico il Grande (nasce nel 1712, regna 1740-1786) SINISTRA: ritratto di Antoine Pesne, 1745 ca. Potsdam, Neue Palais DESTRA: ritratto di Anton Graff, 1780 Una biografia di piacevole lettura: • Alessandro Barbero, Federico il Grande, Palermo: Sellerio, 2007 (non più in commercio ma in diverse biblioteche trentine) DESTRA: Il ritratto del tenente Von Katte, amante del giovane Federico Alcuni dati sui progressi di Berlino nel corso del XVIII secolo: • Crescita demografica: da 90.000 abitanti nel 1745 a 145.000 nel 1786 • Crescita culturale: rispetto alla pubblicazioni di libri in Germania, Berlino balza dall’ottavo al secondo posto, subito dopo Lipsia “Potsdam, Potsdam, questo è ciò che ci serve per essere felici!” Federico II nel 1758 Il castello di Sanssouci (1745-47), arch. -

The Dance of Death

The Dance of Death Hans Holbein, Death goes forth The Dance of Death in Book Illustration by Marcia Collins Catalog to an Exhibition of the Collection in the Ellis Library of the University of Missouri-Columbia April 1 - 30, 1978 On the Occasion of the Annual Spring Meeting of the Midwest Chapter of the American Musicological Society The exhibition and catalog were sponsored by the Department of Music, the Ellis Library and the Graduate School of the University of Missouri Columbia. Photographs in the catalog were taken by Betty Scott. Ellis Library . University of Missouri Columbia, Missouri . 1978 University of Missouri Library Series, 27 Rudolf and Conrad Meyer, The Empress Preface or·several years, even before coming to Columbia, I was interested in a certain aspect of Renaissance icono graphy which I have identified as so cial typology. It had its origins in the humanism of the early Renaissance which first took shape in Italy and spread north throughout Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. In book illustration social typology- the graphic record of man's concern with man--began to present itself as a new and strong current only in the sixteenth century. The term social typology is one for which I must take personal responsibility. The understand ing of its various forms as closely related symp toms of man's understanding of his social position is, I believe, a new approach. By itself the word typology has a number of meanings. For art histor ians it usually means the iconographic juxtaposi tion of Old Testament prophecy and New Testament fulfillment as seen in the early illuminated manu scripts and picture books like the Biblia Pauperum and the Speculum Humanae Salvationis. -

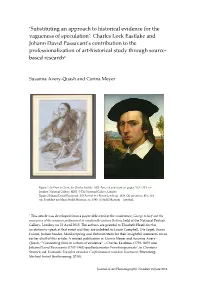

Charles Lock Eastlake and Johann David Passavant’S Contribution to the Professionalization of Art-Historical Study Through Source- Based Research1

‘Substituting an approach to historical evidence for the vagueness of speculation’: Charles Lock Eastlake and Johann David Passavant’s contribution to the professionalization of art-historical study through source- based research1 Susanna Avery-Quash and Corina Meyer Figure 1 Sir Francis Grant, Sir Charles Eastlake, 1853. Pen, ink and wash on paper, 29.3 x 20.3 cm. London: National Gallery, H202. © The National Gallery, London Figure 2 Johann David Passavant, Self-Portrait in a Roman Landscape, 1818. Oil on canvas, 45 x 31.6 cm. Frankfurt am Main: Städel Museum, no. 1585. © Städel Museum – Artothek 1 This article was developed from a paper delivered at the conference, George Scharf and the emergence of the museum professional in nineteenth-century Britain, held at the National Portrait Gallery, London, on 21 April 2015. The authors are grateful to Elizabeth Heath for the invitation to speak at that event and they are indebted to Lorne Campbell, Ute Engel, Susan Foister, Jochen Sander, Marika Spring and Deborah Stein for their insightful comments on an earlier draft of this article. A related publication is: Corina Meyer and Susanna Avery- Quash, ‘“Connecting links in a chain of evidence” – Charles Eastlakes (1793-1865) und Johann David Passavants (1787-1861) quellenbasierter Forschungsansatz’, in Christina Strunck, ed, Kulturelle Transfers zwischen Großbritannien und dem Kontinent, Petersberg: Michael Imhof (forthcoming, 2018). Journal of Art Historiography Number 18 June 2018 Avery-Quash and Meyer ‘Substituting an approach to historical evidence for the vagueness of speculation’ ... Introduction After Sir Charles Eastlake (1793-1865; Fig. 1) was appointed first director of the National Gallery in 1855, he spent the next decade radically transforming the institution from being a treasure house of acknowledged masterpieces into a survey collection which could tell the story of the development of western European painting. -

Meisterkatalog 2021-1

MEISTERGRAPHIK MASTERPRINTS BÜCHER BOOKS ZEICHNUNGEN DRAWINGS SCHWEIZER ANSICHTEN SWISS VIEWS August Laube Buch- und Kunstantiquariat WOLF TRAUT Ca. 1485 Nürnberg 1520 1 l Bildnis des Kurfürsten Friedrich Portrait of the Elector Frederick of von Sachsen nach Lukas Cranach Saxony after Lucas Cranach the El- MEISTERGRAPHIK d.Ae. 1510. Holzschnitt. Wz.: «Ochsen der. 1510. Woodcut. Watermark: “Bull’s MASTERPRINTS kopf». 12,2:9,1 cm. head”. 12,2:9,1 cm. B.134; (fälschlich als Cranach); C. Dodg B.134 (there as Cranach); C. Dodgson. I, son. I, S. 507, Nr. 7; Kat. Cranach Ba p. 507 no. 7; Cat. Cranach Basel 1974, sel 1974, 105; Vgl. Bartrum, German 105; Comp.: Bartrum, German Renais Renaissance Prints 1490–1550, London sance Prints 1490–1550, London 1995 1995, S. 81–83. p. 8183. Dieses Exemplar wurde in der Cranach This woodcut was exhibited in the Lu ausstellung in Basel 1974 ausgestellt cas Cranach exhibition held in Basel in (Bd. I, Nr. 105). Holzschnitt nach Lukas 1974 (Vol. I, No. 105) and was executed Cranachs Kupferstich von 1509. Der after Cranach’s engraving of 1509. The Holzschnitt erschien in Ulrich Pinder‘s woodcut was published in Ulrich Pin «Registrum speculi intellectualis felicita der's “Registrum speculi intellectualis tis humanae... Nuremberg 1510», wel felicitatis humanae... Nuremberg 1510”, ches Friedrich von Sachsen gewidmet where it was dedicated to Friedrich of war. Pinder wurde 1493 Leibarzt des Saxony. In 1493, Pinder became the per Kurfürsten Friedrich und noch im selben sonal physician of the Elector Friedrich Jahr Stadtarzt von Nürnberg, was er bis and held also of the city of Nuremberg. -

Page, Canvas, Wall: Visualising the History of Art

Issue No. 4/2020 Page, Canvas, Wall: Visualising the History of Art Michaela Giebelhausen, PhD, Course Leader, BA Culture, Criticism and Curation, Central St Martins, University of the Arts, London Also published in Susanna Pettersson (ed.), Inspiration – Iconic Works. Ateneum Publications Vol. 132. Helsinki: Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum, 2020, 31–45 In 1909, the Italian poet and founder of the Futurist movement, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti famously declared, ‘[w]e will destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind’.1 He compared museums to cemeteries, ‘[i]dentical, surely, in the sinister promiscuity of so many bodies unknown to one another… where one lies forever beside hated or unknown beings’. This comparison of the museum with the cemetery has often been cited as an indication of the Futurists’ radical rejection of traditional institutions. It certainly made these institutions look dead. With habitual hyperbole Marinetti claimed: ‘We stand on the last promontory of the centuries!… Why should we look back […]? Time and Space died yesterday.’ The brutal breathlessness of Futurist thinking rejected all notions of a history of art. This essay considers how the history of art, embodied in art-historical canons, schools, periods, and aesthetic standards, has been conceptualised through writing, the organisation of collections, and the decoration of new museum buildings. It examines some of the moments in which the page, the canvas and the wall offer seminal and selective visualisations of the history of art and deploy notions of time and space that are complex and contradictory, and far from dead. Writing the history of art The history of art began as a history of artists.