Science Fiction and the Black Political Imagination A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Awarded Action Grants Fiscal Year 2021, Q1

Awarded Action Grants Fiscal Year 2021, Q1 Total Awarded: $159,692 Capital Region Thomas Cole National Historic Site, $5,000 Full House: Illuminating Underrepresented Voices The TCNHS will launch three interpretive tours that encourage group discussion and bring to light underrepresented voices in this nation’s history by illuminating the diverse residents of the historic property. Schenectady County Historical Society, $5,000 Fashion and Identity: Redesigning Historic Dress at SCHS An exhibition by SCHS, in partnership with SUNY Oneonta Fashion & Textile students, will explore the historic importance of women’s fashion in the expression of cultural values and identity, and examine how those ideals have changed over time. Electronic Body Arts, $2,500 50 years of Creativity and Community: eba- Electronic Body Arts. The eba exhibition will highlight how a small arts organization impacted life in the city of Albany over the past 50 years. The exhibition will showcase the performing arts, social interactions, community building, and socio-economic impact of eba. Colonie Senior Service Centers, $5,000 Let's Have a Conversation - Older Women Leading Extraordinary Lives An oral history of the Village of Hamilton, NY, told through stories told by residents about the streets on which they live. Central New York Arts at the Palace, $5,000 Street by Street: A Village as Remembered by Storytellers An oral history of the Village of Hamilton, NY, told through stories told by residents about the streets on which they live. 1 Finger Lakes Friends of Ganondagan $5,000 Haudenosaunee Film Festival The Haudenosaunee Film Festival provides Haudenosaunee filmmakers a culturally significant venue to share reflections of the Haudenosaunee experience engaging both Indigenous and non-Native audiences and will include Q&As and a Youth Workshop. -

Ephemera Labels WWAR EPHEMERA LABELS 1 EXTENDED LABELS

We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85 Ephemera Labels WWAR EPHEMERA LABELS 1 EXTENDED LABELS Larry Neal (Born 1937 in Atlanta; died 1981 in Hamilton, New York) “Any Day Now: Black Art and Black Liberation,” Ebony, August 1969 Jet, January 28, 1971 Printed magazines Collection of David Lusenhop During the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements, publications marketed toward black audiences chronicled social, cultural, and political developments, covering issues of particular concern to their readership in depth. The activities and development of the Black Arts Movement can be traced through articles in Ebony, Black World, and Jet, among other publications; in them, artists documented the histories of their collectives and focused on the purposes and significance of art made by and for people of color. WWAR EPHEMERA LABELS 2 EXTENDED LABELS Weusi Group Portrait, early 1970s Photographic print Collection of Ronald Pyatt and Shelley Inniss This portrait of the Weusi collective was taken during the years in which Kay Brown was the sole female member. She is seated on the right in the middle row. WWAR EPHEMERA LABELS 3 EXTENDED LABELS First Group Showing: Works in Black and White, 1963 Printed book Collection of Emma Amos Jeanne Siegel (Born 1929 in United States; died 2013 in New York) “Why Spiral?,” Art News, September 1966 Facsimile of printed magazine Brooklyn Museum Library Spiral’s name, suggested by painter Hale Woodruff, referred to “a particular kind of spiral, the Archimedean one, because, from a starting point, it moves outward embracing all directions yet constantly upward.” Diverse in age, artistic styles, and interests, the artists in the group rarely agreed; they clashed on whether a black artist should be obliged to create political art. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 This

We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 This exhibition presents the work of more than forty artists and activists who built their careers—and committed themselves to political change—during a time of social tumult in the United States. Beginning in the 1960s, a number of movements to combat social injustice emerged, with the Black Power, Civil Rights, and Women’s Movements chief among them. As active participants in the contemporary art world, the artists in this exhibition created their own radical feminist thinking—working broadly, on multiple fronts—to combat sexism, racism, homophobia, and classism in the art world and within their local communities. As the second-wave Feminist Movement gained strength in the 1970s, women of color found themselves working with, and at times in opposition to, the largely white, middle- class women primarily responsible for establishing the tone, priorities, and methods of the fight for gender equity in the United States. Whether the term feminism was used or not— and in communities of color, it often was not—black women envisioned a revolution against the systems of oppression they faced in the art world and the culture at large. The artists of We Wanted a Revolution employed the emerging methods of conceptual art, performance, film, and video, along with more traditional forms, including printmaking, photography, and painting. Whatever the medium, their innovative artmaking reflected their own aesthetic, cultural, and political priorities. Favoring radical transformation over reformist gestures, these activist artists wanted more than just recognition within the existing professional art world. Instead, their aim was to revolutionize the art world itself, making space for the many and varied communities of people it had largely ignored. -

Vivian Browne’S Tantrum-Throwing Subjects Epitomize White-Male Privilege by Victoria L

Artist Vivian Browne’s Tantrum-Throwing Subjects Epitomize White-Male Privilege by Victoria L. Valentine May 12, 2019 “Seven Deadly Sins” (c. 1968) by Vivian Browne WHEN AFRICAN AMERICAN ARTISTS were weighing issues of race and representation in the 1960s, Vivian Browne (1929-1993) went in a unique direction. She began making drawings and paintings of white men in various states of rant, rage, and rebellion. Their white dress shirts and neckties indicate a certain professional status. They are men of privilege and power whose behavior is debasing. Considered her first major body of work, Browne called the series Little Men. Her subjects clench their fists and cross their arms in frustration, guzzle sloppily from bottles, and grasp their crotches pleasuring themselves. One holds his mouth wide open performing a vocal tantrum. In “Seven Deadly Sins,” a subject literally puts his foot in his mouth. Another work is titled “Wall Street Jump,” indicating the social realm, mindset, and financial status of its subjects. The expressive images make a political statement about white male patriarchy. Meanwhile, Browne’s masterful use of color serves a variety of purposes—defining space, indicating emotion, and guiding the viewer’s eye. The scenes that unfold across the 50-year-old works portray stereotyped personas that resonate today, calling to mind 21st century phenomena—the actions of those who might rail against “reverse” discrimination, the shameful and more blatant behavior exhibited by targets of the #MeToo Movement, and the brazen conduct of the current President of the United States. Installation view of “Vivian Browne: Little Men,” (Feb. -

Press Release March 2017

Press Release March 2017 The Brooklyn Museum Presents We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 Groundbreaking exhibition featuring more than forty artists opens April 21 A Year of Yes: Reimagining Feminism at the Brooklyn Museum continues with We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85. Focusing on the work of more than forty black women artists from an under- recognized generation, the exhibition highlights a remarkable group of artists who committed themselves to activism during a period of profound social change marked by the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements, the Women’s Movement, the Anti-War Movement, and the Gay Liberation Movement, among others. The groundbreaking exhibition reorients conversations around race, feminism, political action, art production, and art history, writing a broader, bolder story of the Jan van Raay (American, born 1942). Faith Ringgold (right) and Michele Wallace (middle) at Art Workers Coalition Protest, Whitney Museum, 1971. Courtesy of Jan van multiple feminisms that shaped this period. Raay, Portland, OR, 305-37. © Jan van Raay Curated by Catherine Morris, Sackler Family Senior Curator for the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist printmaking, reflecting the aesthetics, politics, cultural Art, and Rujeko Hockley, Assistant Curator at the priorities, and social imperatives of this period. It begins Whitney Museum of American Art and former Assistant in the mid-1960s, as younger activists began shifting Curator of Contemporary Art at the Brooklyn Museum, from the peaceful public disobedience favored by the We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 is Civil Rights Movement to the more forceful tactics of on view April 21 through September 17, 2017. -

LORRAINE O'grady with Jarrett Earnest | the Brooklyn Rail

LORRAINE O’GRADY with Jarrett Earnest | The Brooklyn Rail http://www.brooklynrail.org/2016/02/art/lorraine-ogrady-with-ja... Art February 3rd, 2016 LORRAINE O’GRADY with Jarrett Earnest Lorraine O’Grady crashed into the New York art world as Mademoiselle Bourgeoise Noire in 1980, shouting poems and whipping herself to the distinct displeasure of fellow exhibition-goers. In the subsequent thirty-five years, she’s created an elaborate and tremendously important body of performances, photos, collages, and writing. Her most famous, and much anthologized, 1992 essay, “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity,” is a staple of feminist art history. She recently had a survey exhibition, Lorraine O’Grady: Where Margins Become Centers, at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard University; forty photographs from her 1983 performance Art Is. .(where she entered her own float into the African-American Day Parade in Harlem) are on display at the Studio Museum in Harlem through March 6; and her series “Cutting Out the New York Times” (1977/2010) is included in CUT-UP: Contemporary Collage and Cut-Up Histories Through A Feminist Lens, at Franklin Street Works in Stamford, Connecticut (through April 3). O’Grady met with Jarrett Earnest to discuss Flannery O’Connor as a philosopher of the margins, emotions in Egyptian sculpture, and the genius of Michael Jackson. Jarrett Earnest (Rail): A lot of your work relates to archives, both in content and form. When you started putting together your own website, were you thinking about it in terms of framing it as an archive? Lorraine O’Grady: I did it because I thought I’d disappeared in many people’s minds—Connie Butler being one exception. -

Ebook Download New York City Magnetic Bookmark

NEW YORK CITY MAGNETIC BOOKMARK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Galison,Mariko Jesse | 6 pages | 29 Jan 2013 | Galison Books | 9780735336858 | English | New York, United States New York City Magnetic Bookmark PDF Book They are often unbearably crowded then, which can detract greatly from your enjoyment of the show. As the stars begin to shine, big city lights beckon from a myriad of restaurants, lounges, clubs, and theaters. Have dinner at the chic, art deco Odeon W Broadway, at Thomas in TriBeCa, which has been serving consistently good food since the s. When looking over its "Asian street food" menu, consider trying the ginger margaritas and the mushroom egg rolls. Run by actors, the place is a kind of shrine to the way Coney Island used to be. New Yorkers often come here to celebrate special events and although it's pricey, it's an unforgettable New York experience. From the spring through the fall, the Mets at Shea Stadium in Queens and the Yankees at Yankee Stadium in the Bronx often play day games on the weekends, while the horses run all afternoon at Belmont Park Tuesdays through Sundays. New York restaurants run the gamut, from the astronomically expensive to the inexpensive, from the enormous to the pocket-sized, from the snooty to the happy-to-serve, from haute cuisine to take-out food. But the truth is that even the most budget-conscious traveler can still have just as much fun during a trip to the Big Apple. If you can eat another bite, you can savor a plate of homemade chocolates. -

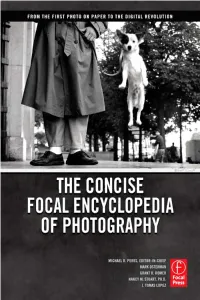

The Concise Focal Encyclopedia of Photography

The Concise Focal Encyclopedia of Photography Prelims-K80998.indd i 6/20/07 6:14:35 PM This page intentionally left blank The Concise Focal Encyclopedia of Photography From the First Photo on Paper to the Digital Revolution MICHAEL R. PERES, MARK OSTERMAN, GRANT B. R OMER, NANCY M. STUART , Ph.D., J. TOMAS LOPEZ AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • O XFORD • PARIS • S AN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • S INGAPORE • S YDNEY • TOKYO Focal Press is an imprint of Else vier Prelims-K80998.indd iii 6/20/07 6:14:37 PM Acquisitions Editor : Diane Heppner Publishing Ser vices Manager : George Mor rison Senior Project Manager : Brandy Lilly Associate Acquisitions Editor : Valerie Gear y Assistant Editor : Doug Shults Marketing Manager : Christine Degon V eroulis Cover Design: Alisa Andreola Interior Design: Alisa Andreola Focal Press is an imprint of Else vier 30 Cor porate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford O X2 8DP, UK Copyright © 2008, Else vier Inc. All rights reser ved. No par t of this publication ma y be reproduced, stored in a retrie val system, or transmitted in an y form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocop ying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written per mission of the publisher . Permissions ma y be sought directly from Else vier’s Science & T echnology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: ( ϩ44) 1865 843830, fax: ( ϩ44) 1865 853333, E-mail: per missions@else vier.com. You may also complete your request on-line via the Else vier homepage (http://else vier.com), by selecting “Suppor t & Contact” then “Cop yright and Permission” and then “Obtaining P ermissions. -

To Read Exhibition Catalog

1 Black Documents: Mosaic Literary Conference explores Black Documents historical and contemporary presentations of black Mosaic Literary Conference identity in literature and photography; and how self- Saturday, November 25, 2017, 11-6pm affirming imagery and text can counter negative Bronx Museum of the Arts stereotypes. The conference consists of workshops, 1040 Grand Concourse, Bronx, NYC panels, talks, and screenings. www.BlackDocuments.com To this end, the conference will also present photography exhibits Jamel Shabazz: Black Documents ALL EVENTS ARE FREE. and Black Documents: Freedom. This event is made possible with donations and public funds from Humanities New York, Citizens Committee for New York City. In-kind support is provided by The Bronx Museum of the Arts and The Andrew Freedman Home. Additional support has been provided by community partners AALBC.com, BxArts Factory, Bronx Cultural Collective, The Center for Black Literature, En Foco, The Laundromat Project, The Roew, WideVision Photography, and Word Up Bookstore. The Literary Freedom Project is a member of the Urban Arts Cooperative -supporting artists in underserved communities. 2 Jamel Shabazz: Black Documents Black Documents Opening Reception Photography exhibition November 25, 6-9pm November 25 to December 15, 2017 Andrew Freedman Home Andrew Freedman Home 1125 Grand Concourse, Bronx, NYC Black Documents: Freedom Artist Talks Photography exhibition Andrew Freedman Home November 25 to December 15, 2017 1125 Grand Concourse, Bronx, NYC Photographers: Laylah Amatullah Barrayn, Lola Flash, Danny Ramon Peralta, Thursday, November 30, 6-8pm Edwin Torres, and Michael Young Photographers from Black Documents: Andrew Freedman Home Freedom. Coreen Simpson, facilitator Thursday, December 7, 6-8pm Jamel Shabazz and Laura James, curator 3 Jamel Shabazz: Black Documents: Freedom This publication accompanies the exhibitions Jamel Shabazz: Black Documents and Black Documents: Freedom, organized by Laura James and Ron Kavanaugh. -

The Salon at Dc

THE SALON AT DC THE SALON AT THE W ING DC CURATED BY LOLITA CROS 1056 THOMAS JEFFERSON STREET NW, WASHINGTON, DC Table of Contents 2 Angela Alba 47 Senga Nengudi 5 Lana Barkin 48 Lorraine O’Grady 6 Katherine Blackburne 51 Erin O’Keefe 9 Nydia Blas 52 Elsa Hansen Oldham 10 Deborah Brown 55 Louise Parker 13 Carly Burnell 56 Tessa Perutz 14 Clara Claus 59 Erica Prince 17 Yasmine Diaz 60 Emma Ressel 18 Jameela Elfaki 65 Katherine Simóne Reynolds 21 Kristin Gaudio Endsley 66 Pauline de Roussy de Sales 22 Devra Freelander 71 Alexandra Rubinstein 25 Linnéa Gad 74 Jo Shane 28 Alba Hodsoll 77 Coreen Simpson 31 Emily Hope 78 Penny Slinger 32 February James 81 Nancy Spero 35 Rhea Karam 82 Katy Stubbs 87 Adrienne Elise Tarver 38 Izzy Leung 90 Suné Woods 43 Katrina Majkut 44 Laura McGinley The Salon at The Wing is a permanent exhibition with rotating artwork by female artists displayed all throughout the spaces. Despite their undeniable influence, women in the arts have long faced the same exclusion and marginalization as they have in other industries. The works in The Salon at The Wing stand as a statement to the power and creative force of these women. Curated by consultant and member Lolita Cros, the show includes 85 works by 38 female artists. Similar to the warmth of a collector’s home, the viewer is privy to the unique experience of seeing fashion photographers and painters displayed alongside sculptors and illustrators. Bringing established and up-and-coming artists together, Cros assembled the works to interact with each other, outside of the traditional hierarchy of the art world. -

The Black American Women Who Made Their Own Art World

The Black American Women Who Made Their Own Art World We Wanted a Revolution at the Brooklyn Museum tracks the shape-shifting radicalism of black women artists, authors, filmmakers, dancers, gallerists, and public figures between 1965 and 1985. by Jessica Bell Brown August 7, 2017 Howardena Pindell, Carnival at Ostende, 1977, mixed media on canvas, 93 1/2 x 117 1/4 inches On the heels of the Civil Rights movement, in a 1971 New York Times article, Toni Morrison made a terse assessment of the downstream effects of second-wave feminism, as observed by black women: What do black women feel about Women’s Lib? Distrust. It is white, therefore suspect. In spite of the fact that liberating movements in the black world have been catalysts for white feminism, too many movements and organizations have made deliberate overtures to enroll blacks and have ended up by rolling them. They don’t want to be used again to help somebody gain power — a power that is carefully kept out of their hands. They look at white women and see them as the enemy — for they know that racism is not confined to white men, and that there are more white women than men in this country, and that 53 percent of the population sustained an eloquent silence during times of greatest stress. Morrison’s indictment of the exclusionary politics of white feminists seems eerily prescient for today’s times, especially in the immediate aftermath of Trump’s election. Black women, as the novelist recounts, “had nothing to fall back on; not maleness, not whiteness, not ladyhood, not anything.