Homoptera: Cicadelloidea and Membracoidea) J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tuff Crater Insects

«L» «NZAC_CODE1», «LOC_WIDE», «LOCALITY», «LOC_NARROW», «LOC_Specific» Herbivores found at locality, all observations listed by species within major group 192 Acalitus australis (Lamb, 1952) (Arachnida, Acari: Prostigmata, Eriophyoidea, Eriophyidae) (Puriri erineum mite). Biostatus: endemic CFA1303_N02: record 31/03/2013 leaf erineum seen 208 Aceria calystegiae (Lamb, 1952) (Arachnida, Acari: Prostigmata, Eriophyoidea, Eriophyidae) (Bindweed gall mite). Biostatus: endemic CFA1303_N06: record 31/03/2013 pocket galls common 222 Aceria melicyti Lamb, 1953 (Arachnida, Acari: Prostigmata, Eriophyoidea, Eriophyidae) (Mahoe leaf roll mite). Biostatus: endemic CFA1303_N30: record 31/03/2013 a few leaf edge roll galls seen 241 Eriophyes lambi Manson, 1965 (Arachnida, Acari: Prostigmata, Eriophyoidea, Eriophyidae) (Pohuehue pocket gall mite). Biostatus: endemic CFA1303_N20: record 31/03/2013 pocket galls on leaves 2997 Illeis galbula Mulsant, 1850 (Insecta, Coleoptera, Cucujoidea, Coccinellidae) (Fungus eating ladybird). Biostatus: adventive CFA1303_N04: record 31/03/2013 large larva on puriri leaf, no obvious fungal food 304 Neomycta rubida Broun, 1880 (Insecta, Coleoptera, Curculionoidea, Curculionidae) (Pohutukawa leafminer). Biostatus: endemic CFA1303_N32: record 31/03/2013 holes in new leaves 7 Liriomyza chenopodii (Watt, 1924) (Insecta, Diptera, Opomyzoidea, Agromyzidae) (Australian beet miner). Biostatus: adventive CFA1303_N18: record 31/03/2013 a few narrow leaf mines 9 Liriomyza flavocentralis (Watt, 1923) (Insecta, Diptera, Opomyzoidea, Agromyzidae) (Variable Hebe leafminer). Biostatus: endemic CFA1303_N08: record 31/03/2013 a few mines on shrubs planted near Wharhouse entrance 21 Liriomyza watti Spencer, 1976 (Insecta, Diptera, Opomyzoidea, Agromyzidae) (New Zealand cress leafminer). Biostatus: endemic CFA1303_N07: record 31/03/2013 plant in shade with leaf mines, one leaf with larval parasitoids, larva appears to be white 362 Myrsine shoot tip gall sp. -

ARTHROPODA Subphylum Hexapoda Protura, Springtails, Diplura, and Insects

NINE Phylum ARTHROPODA SUBPHYLUM HEXAPODA Protura, springtails, Diplura, and insects ROD P. MACFARLANE, PETER A. MADDISON, IAN G. ANDREW, JOCELYN A. BERRY, PETER M. JOHNS, ROBERT J. B. HOARE, MARIE-CLAUDE LARIVIÈRE, PENELOPE GREENSLADE, ROSA C. HENDERSON, COURTenaY N. SMITHERS, RicarDO L. PALMA, JOHN B. WARD, ROBERT L. C. PILGRIM, DaVID R. TOWNS, IAN McLELLAN, DAVID A. J. TEULON, TERRY R. HITCHINGS, VICTOR F. EASTOP, NICHOLAS A. MARTIN, MURRAY J. FLETCHER, MARLON A. W. STUFKENS, PAMELA J. DALE, Daniel BURCKHARDT, THOMAS R. BUCKLEY, STEVEN A. TREWICK defining feature of the Hexapoda, as the name suggests, is six legs. Also, the body comprises a head, thorax, and abdomen. The number A of abdominal segments varies, however; there are only six in the Collembola (springtails), 9–12 in the Protura, and 10 in the Diplura, whereas in all other hexapods there are strictly 11. Insects are now regarded as comprising only those hexapods with 11 abdominal segments. Whereas crustaceans are the dominant group of arthropods in the sea, hexapods prevail on land, in numbers and biomass. Altogether, the Hexapoda constitutes the most diverse group of animals – the estimated number of described species worldwide is just over 900,000, with the beetles (order Coleoptera) comprising more than a third of these. Today, the Hexapoda is considered to contain four classes – the Insecta, and the Protura, Collembola, and Diplura. The latter three classes were formerly allied with the insect orders Archaeognatha (jumping bristletails) and Thysanura (silverfish) as the insect subclass Apterygota (‘wingless’). The Apterygota is now regarded as an artificial assemblage (Bitsch & Bitsch 2000). -

Homologies of the Head of Membracoidea Based on Nymphal Morphology with Notes on Other Groups of Auchenorrhyncha (Hemiptera)

Eur. J. Entomol. 107: 597–613, 2010 http://www.eje.cz/scripts/viewabstract.php?abstract=1571 ISSN 1210-5759 (print), 1802-8829 (online) Homologies of the head of Membracoidea based on nymphal morphology with notes on other groups of Auchenorrhyncha (Hemiptera) DMITRY A. DMITRIEV Illinois Natural History Survey, Institute of Natural Resource Sustainability at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, Illinois, USA; e-mail: [email protected] Key words. Hemiptera, Membracoidea, Cicadellidae, Cicadoidea, Cercopoidea, Fulgoroidea, head, morphology, ground plan Abstract. The ground plan and comparative morphology of the nymphal head of Membracoidea are presented with particular emphasis on the position of the clypeus, frons, epistomal suture, and ecdysial line. Differences in interpretation of the head structures in Auchenorrhyncha are discussed. Membracoidea head may vary more extensively than heads in any other group of insects. It is often modified by the development of an anterior carina, which apparently was gained and lost multiple times within Membracoidea. The main modifications of the head of Membracoidea and comparison of those changes with the head of other superfamilies of Auchenorrhyncha are described. INTRODUCTION MATERIAL AND METHODS The general morphology of the insect head is relatively Dried and pinned specimens were studied under an Olympus well studied (Ferris, 1942, 1943, 1944; Cook, 1944; SZX12 microscope with SZX-DA drawing tube attachment. DuPorte, 1946; Snodgrass, 1947; Matsuda, 1965; Detailed study of internal structures and boundaries of sclerites Kukalová-Peck, 1985, 1987, 1991, 1992, 2008). There is based on examination of exuviae and specimens cleared in are also a few papers in which the hemipteran head is 5% KOH. -

Hemiptera: Cicadellidae: Megophthalminae)

Zootaxa 2844: 1–118 (2011) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2011 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) ZOOTAXA 2844 Revision of the Oriental and Australian Agalliini (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae: Megophthalminae) C.A.VIRAKTAMATH Department of Entomology, University of Agricultural Sciences, GKVK, Bangalore 560065, India. E-mail: [email protected] Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by C. Dietrich: 15 Dec. 2010; published: 29 Apr. 2011 C.A. VIRAKTAMATH Revision of the Oriental and Australian Agalliini (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae: Megophthalminae) (Zootaxa 2844) 118 pp.; 30 cm. 29 Apr. 2011 ISBN 978-1-86977-697-8 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-86977-698-5 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2011 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2011 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) 2 · Zootaxa 2844 © 2011 Magnolia Press VIRAKTAMATH Table of contents Abstract . 5 Introduction . 5 Checklist of Oriental and Australian Agallini . 8 Key to genera of the Oriental and Australian Agalliini . 10 Genus Agallia Curtis . 11 Genus Anaceratagallia Zachvatkin Status revised . 15 Key to species of Anaceratagallia of the Oriental region . -

Ulopsina, a Remarkable New Ulopine Leafhopper Genus from China Author(S): Wu Dai, Chandra A

Ulopsina, a Remarkable new Ulopine Leafhopper Genus from China Author(s): Wu Dai, Chandra A. Viraktamath and Yalin Zhang Source: Journal of Insect Science, 12(70):1-9. 2012. Published By: Entomological Society of America DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1673/031.012.7001 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1673/031.012.7001 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Journal of Insect Science: Vol. 12 | Article 70 Dai et al. Ulopsina, a remarkable new ulopine leafhopper genus from China Wu Dai1a, Chandra A. Viraktamath1,2b, and Yalin Zhang1c* 1Key Laboratory of Plant Protection Resources and Pest Management, Ministry of Education, Entomological Museum, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, Shaanxi 712100, China 2Department of Entomology, University of Agricultural Sciences, GKVK, Bangalore 560065, India Abstract An unusual new cicadellid genus, Ulopsina gen. -

Evolution of the Insects

CY501-C08[261-330].qxd 2/15/05 11:10 PM Page 261 quark11 27B:CY501:Chapters:Chapter-08: 8 TheThe Paraneopteran Orders Paraneopteran The evolutionary history of the Paraneoptera – the bark lice, fold their wings rooflike at rest over the abdomen, but thrips true lice, thrips,Orders and hemipterans – is a history beautifully and Heteroptera fold them flat over the abdomen, which reflected in structure and function of their mouthparts. There probably relates to the structure of axillary sclerites and other is a general trend from the most generalized “picking” minute structures at the base of the wing (i.e., Yoshizawa and mouthparts of Psocoptera with standard insect mandibles, Saigusa, 2001). to the probing and puncturing mouthparts of thrips and Relationships among paraneopteran orders have been anopluran lice, and the distinctive piercing-sucking rostrum discussed by Seeger (1975, 1979), Kristensen (1975, 1991), or beak of the Hemiptera. Their mouthparts also reflect Hennig (1981), Wheeler et al. (2001), and most recently by diverse feeding habits (Figures 8.1, 8.2, Table 8.1). Basal Yoshizawa and Saigusa (2001). These studies generally agree paraneopterans – psocopterans and some basal thrips – are on the monophyly of the order Hemiptera and most of its microbial surface feeders. Thysanoptera and Hemiptera suborders and a close relationship of the true lice (order independently evolved a diet of plant fluids, but ancestral Phthiraptera) with the most basal group, the “bark lice” (Pso- heteropterans were, like basal living families, predatory coptera), which comprise the Psocodea. One major issue is insects that suction hemolymph and liquified tissues out of the position of thrips (order Thysanoptera), which either their prey. -

Evolutionary Drivers of Temporal and Spatial Host Use Patterns in Restio Leafhoppers Cephalelini (Cicadellidae)

Evolutionary drivers of temporal and spatial host use patterns in restio leafhoppers Cephalelini (Cicadellidae) By Willem Johannes Augustyn Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Science at Stellenbosch University Promoters: Allan George Ellis and Bruce Anderson December 2015 1 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis/dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Copyright © 2015 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved 2 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract Understanding how divergent selection results in the evolution of reproductive isolation (i.e. speciation) is an important goal in evolutionary biology. Populations of herbivorous insects using different host plant species can experience divergent selection from multiple selective pressures which can rapidly lead to speciation. Restio leafhoppers are a group of herbivorous insect species occurring within the Cape Floristic Region (CFR) of South Africa. They are specialised on different plant species in the Restionaceae family. Throughout my thesis I investigated how bottom- up (i.e. plant chemistry/morphology of host plant species) and top-down (i.e. predation and competition) factors drive specialisation and divergence in restio leafhoppers. I also investigated interspecific competition as an important determinant of restio leafhopper community structure. -

Auchenorrhyncha (Insecta: Hemiptera): Catalogue

The Copyright notice printed on page 4 applies to the use of this PDF. This PDF is not to be posted on websites. Links should be made to: FNZ.LandcareResearch.co.nz EDITORIAL BOARD Dr R. M. Emberson, c/- Department of Ecology, P.O. Box 84, Lincoln University, New Zealand Dr M. J. Fletcher, Director of the Collections, NSW Agricultural Scientific Collections Unit, Forest Road, Orange, NSW 2800, Australia Dr R. J. B. Hoare, Landcare Research, Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand Dr M.-C. Larivière, Landcare Research, Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand Mr R. L. Palma, Natural Environment Department, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, P.O. Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand SERIES EDITOR Dr T. K. Crosby, Landcare Research, Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand Fauna of New Zealand Ko te Aitanga Pepeke o Aotearoa Number / Nama 63 Auchenorrhyncha (Insecta: Hemiptera): catalogue M.-C. Larivière1, M. J. Fletcher2, and A. Larochelle3 1, 3 Landcare Research, Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand 2 Industry & Investment NSW, Orange Agricultural Institute, Orange NSW 2800, Australia 1 [email protected], 2 [email protected], 3 [email protected] with colour photographs by B. E. Rhode Manaaki W h e n u a P R E S S Lincoln, Canterbury, New Zealand 2010 4 Larivière, Fletcher & Larochelle (2010): Auchenorrhyncha (Insecta: Hemiptera) Copyright © Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd 2010 No part of this work covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means (graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping information retrieval systems, or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. -

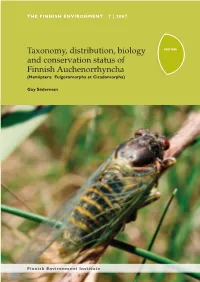

Taxonomy, Distribution, Biology and Conservation Status Of

TAXONOMY, DISTRIBUTION, BIOLOGY AND CONSERVATION STATUS OF FINNISH AUCHENORRHYNCHA THE FINNISH ENVIRONMENT 7 | 2007 The publication is a revision of the Finnish froghopper and leafhopper fauna Taxonomy, distribution, biology NATURE (Hemiptera: Auchenorrhyncha) using modern systematics and nomenclature and combining a vast amount of recent findings with older ones. The biology and conservation status of of each species is shortly discussed and a link is given to the regularly updated species distribution atlas on the web showing detailed distribution and phenol- Finnish Auchenorrhyncha ogy of each species. An intermittent assessment of the conservation status of all (Hemiptera: Fulgoromorpha et Cicadomorpha) species is made and the threat factors are shortly discussed. Guy Söderman THE FINNISH ENVIRONMENT 7 | 2007 ISBN 978-952-11-2594-2 (PDF) ISSN 1796-1637 (verkkoj.) Finnish Environment Institute THE FINNISH ENVIRONMENT 7 | 2007 Taxonomy, distribution, biology and conservation status of Finnish Auchenorrhyncha (Hemiptera: Fulgoromorpha et Cicadomorpha) Guy Söderman Helsinki 2007 FINNISH ENVIRONMENT INSTITUTE THE FINNISH ENVIRONMENT 7 | 2007 Finnish Environment Institute Expert Services Department Page layout: Pirjo Lehtovaara Front cover: Freshly hatched Mountain Cicada (Cicadetta montana, photo: Jaakko Lahti) The publication is only available in the internet: www.environment.fi/publications ISBN 978-952-11-2594-2 (PDF) ISSN 1796-1637 (verkkoj.) PREFACE The latest assessment of the Finnish species in year 2000 revealed a strong defiency in the knowledge of planthoppers and leafhoppers. About one third of all species could not be properly assessed and were classified as data deficient. A year later a national Expert Group on Hemiptera was formed to increase the basic knowledge of this insect order. -

(Psocoptera: Psyllipsocidae) from a Brazilian Cave

Microcrystals coating the wing membranes of a living insect (Psocoptera: SUBJECT AREAS: ZOOLOGY Psyllipsocidae) from a Brazilian cave ECOLOGY Charles Lienhard1, Rodrigo L. Ferreira2, Edwin Gnos1, John Hollier1, Urs Eggenberger3 & Andre´ Piuz1 NANOBIOTECHNOLOGY PHENOMENA AND PROCESSES 1Natural History Museum of the City of Geneva, CP 6434, CH-1211 Geneva 6, Switzerland, 2Federal University of Lavras, Biology Department (Zoology), CP 3037, CEP 37200-000 Lavras (MG), Brazil, 3Institute for Geological Sciences, University of Bern, Baltzerstrasse 1-3, CH-3012 Bern, Switzerland. Received 15 March 2012 Two specimens of Psyllipsocus yucatan with black wings were found with normal individuals of this species Accepted on guano piles produced by the common vampire bat Desmodus rotundus. These specimens have both pairs 3 May 2012 of wings dorsally and ventrally covered by a black crystalline layer. They did not exhibit any signs of reduced vitality in the field and their morphology is completely normal. This ultrathin (1.5 mm) crystalline layer, Published naturally deposited on a biological membrane, is documented by photographs, SEM micrographs, energy 15 May 2012 dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) and X-ray diffractometry (XRD). The crystalline deposit contains iron, carbon and oxygen, but the mineral species could not be identified. Guano probably played a role in its formation; the presence of iron may be a consequence of the excretion of iron by the common vampire bat. Correspondence and This enigmatic phenomenon lacks obvious biological significance but may inspire bionic applications. Nothing similar has ever been observed in terrestrial arthropods. requests for materials should be addressed to C.L. (charleslienhard@ he observation reported here is an accessory result of the studies of the Brazilian cave fauna initiated by the bluewin.ch) Federal University of Lavras (Minas Gerais state, Brazil). -

Molecular Phylogeny of Triatomini (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae)

Justi et al. Parasites & Vectors 2014, 7:149 http://www.parasitesandvectors.com/content/7/1/149 RESEARCH Open Access Molecular phylogeny of Triatomini (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae) Silvia Andrade Justi1,ClaudiaAMRusso1, Jacenir Reis dos Santos Mallet2, Marcos Takashi Obara3 and Cleber Galvão4* Abstract Background: The Triatomini and Rhodniini (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) tribes include the most diverse Chagas disease vectors; however, the phylogenetic relationships within the tribes remain obscure. This study provides the most comprehensive phylogeny of Triatomini reported to date. Methods: The relationships between all of the Triatomini genera and representatives of the three Rhodniini species groups were examined in a novel molecular phylogenetic analysis based on the following six molecular markers: the mitochondrial 16S; Cytochrome Oxidase I and II (COI and COII) and Cytochrome B (Cyt B); and the nuclear 18S and 28S. Results: Our results show that the Rhodnius prolixus and R. pictipes groups are more closely related to each other than to the R. pallescens group. For Triatomini, we demonstrate that the large complexes within the paraphyletic Triatoma genus are closely associated with their geographical distribution. Additionally, we observe that the divergence within the spinolai and flavida complex clades are higher than in the other Triatoma complexes. Conclusions: We propose that the spinolai and flavida complexes should be ranked under the genera Mepraia and Nesotriatoma. Finally, we conclude that a thorough morphological investigation of the paraphyletic genera Triatoma and Panstrongylus is required to accurately assign queries to natural genera. Keywords: Triatomini, Species complex, Monophyly Background Mepraia and Nesotriatoma with Triatoma, which is the Chagas disease, or American Trypanosomiasis, is one of most diverse genus of the subfamily. -

Leafhoppers and Their Morphology, Biology, Ecology and Contribution in Ecosystem: a Review Paper

International Journal of Entomology Research International Journal of Entomology Research ISSN: 2455-4758 Impact Factor: RJIF 5.24 www.entomologyjournals.com Volume 3; Issue 2; March 2018; Page No. 200-203 Leafhoppers and their morphology, biology, ecology and contribution in ecosystem: A review paper Bismillah Shah*, Yating Zhang School of Plant Protection, Anhui Agricultural University, Hefei, Anhui Province, China Abstract The present study was conducted at Anhui Agricultural University, Hefei, China during 2018 and was compiled as a review paper from internationally recognized published articles plus Annual/Environmental reports of documented organizations. Leafhoppers (Auchenorrhynca: Cicadellidae) are small, very active jumping insects that commonly feed on a variety of host plants. Leafhoppers are agricultural pests while some species are also vectors of many plant viruses. Around 25000 species of leafhoppers have been identified and described by the experts. The study on leafhoppers plays a vital role in understanding their roles in our agroecosystem. This review paper summarizes the basic information regarding the morphology, biology and ecology of leafhoppers. Keywords: agricultural pest, auchenorrhynca, cicadellidae, leafhopper, vector Introduction usually use during overwintering. To control leafhoppers Insect species of the animal kingdom that belongs to family biologically, entomopathogenic fungi and parasitoids are used Cicadellidae are commonly known as leafhoppers. They are (Dietrich, 2004) [13]. found in various zones of the planet in tropical and subtropical Leafhoppers are the members of order Hemiptera followed by ecosystems (Dietrich, 2005) [14]. These small insects known infraorder Cicadomorpha, superfamily Membracoidea and as hoppers have piercing-sucking type of mouthparts family Cicadellidae respectively. Leafhoppers are further (Dietrich, 2004) [13] hence suck plant sap from trees, grasses placed in about 40 subfamilies (Web source A) [49].