Neighbourhoods and Potential Access to Health Care the Role of Spatial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix III: Provisional Scenario 10

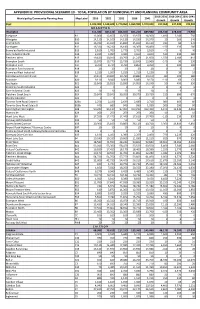

APPENDIX III: PROVISIONAL SCENARIO 10 - TOTAL POPULATION BY MUNICIPALITY AND PLANNING COMMUNITY AREA 2016-2031 2016-2041 2031-2041 Municipality/Community Planning Area Map Label 2016 2021 2031 2036 2041 Growth Growth Growth Peel 1,433,000 1,538,600 1,770,060 1,869,990 1,970,040 337,060 537,040 199,980 B R A M P T O N Brampton 611,480 687,150 816,020 855,220 889,980 204,540 278,500 73,960 Snelgrove B1 12,060 12,650 13,550 13,970 14,300 1,490 2,240 750 Westgate B10 14,110 14,100 14,130 14,230 14,370 20 260 240 Central Park B11 16,030 15,910 15,840 15,960 16,110 -190 80 270 Northgate B12 16,330 16,230 16,180 16,300 16,460 -150 130 280 Bramalea North Industrial B13 2,810 2,780 2,770 2,790 2,810 -40 0 40 Gore Industrial North B14 2,910 3,090 3,440 3,660 3,820 530 910 380 Fletchers West B15 19,420 20,010 20,790 21,220 21,600 1,370 2,180 810 Brampton South B16 13,870 13,770 13,730 13,840 13,960 -140 90 230 Brampton East B17 9,760 9,730 9,760 9,850 9,950 0 190 190 Brampton East Industrial B18 20 20 20 20 20 0 0 0 Bramalea West Industrial B19 1,210 1,200 1,210 1,210 1,220 0 10 10 Sandalwood Industrial East B2 10,870 10,820 10,790 10,880 10,970 -80 100 180 Avondale B20 9,110 9,040 9,000 9,080 9,170 -110 60 170 Southgate B21 13,840 13,810 13,890 14,050 14,240 50 400 350 Bramalea South Industrial B22 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Gore Industrial South B23 10 10 10 10 10 0 0 0 Fletchers Creek South B24 29,840 29,840 30,050 30,370 30,720 210 880 670 Steeles Industrial B25 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Toronto Gore Rural Estate A B26a 2,250 2,430 2,630 2,680 2,710 380 460 80 Toronto -

Churchill Meadows Community Profile

CITY OF MISSISSAUGA Planning and Building Department February, 2004 Churchill Meadows Community Profile History processing of development applications. mix of uses, a connected system of natural From 1987 to 1997 draft secondary plans features, parks, schools and stormwater The Churchill Meadows Residential District were prepared and the two areas were management facilities, a grid pattern of was originally part of the Town of Oakville combined into the Churchill Meadows streets and the creation of neighbourhood and designated for agricultural uses. With Planning District. During this time the last units. Lands in the north and south part of the advent of Regional Government in 1974, remaining greenfield was occupied by the planning district are under construction the City of Mississauga was established and several working farms, along with individual and applications for the central area are Churchill Meadows was incorporated residences along the east and west sides of currently being processed. through the extension of its westerly Tenth Line West and the east side Table 1 - 2001 Total Population boundary to Ninth Line. of Ninth Line. Churchill In 1997 urban design guidelines The Official (Primary) Plan of 1981 identified Churchill Meadows as the major land uses for this area as were prepared for the Churchill Mississauga Meadows a % of residential for the lands north of Eglinton Meadows Planning District Avenue West (Winston Churchill Residential providing direction to the public Mississauga District) and mixed industrial and commercial and private sectors with respect to Male 2,675 301,495 0.9% the design intent of the City in for the lands located south of Eglinton Fe m ale 2,770 309,235 0.9% Avenue West (Central Business District). -

School/Library Name | Nom De L'école/De La Bibliothèque City/Town

LOOK WHO WAS SIGNED UP FOR I READ CANADIAN DAY IN 2020? Province/Territory School/Library Name | Nom de l'école/de la City/Town | Ville | Province / bibliothèque Territoire A. B. Lucas S.S. London Ontario Abbotsford Traditional Middle School Abbotsford British Columbia Abraar Elementary School Ottawa Ontario Abraham Erb Public School Waterloo Ontario Adam Beck Ps Toeonto Ontario Adelaide W.G. MacDonald Strathroy Ontario Admaston/Bromley Public Library Douglas Ontario Agincourt Road Public School Ottawa Ontario Ajax Public Library Ajax Ontario Alcona Glen Innisfil Ontario Alcona Glen Elementary School Innisfil Ontario Aldershot High School Burlington Ontario Alexander von Humboldt German International Baie D Urfé Quebec School Alf Cuthbert School Moosehorn Manitoba Algonquin P.S Woodstock Ontario Algonquin P.S Woodstock Ontario All Saints School Mississauga Ontario Allan A. Martin Sr. Public School Mississauga Ontario Allan Drive Middle School Bolton Ontario Allan Drive Middle School Bolton Ontario Allandale Heights P.S. Barrie Ontario Alliance Public School 700 Stones St., North Bay Ontario Alliance Public School North Bay Ontario Allion Elementary LaSalle Quebec Alliston Union PS Alliston Ontario Alloa Public School - Caledon Caledon Ontario Almaguin Highlands Secondary School Library South River Ontario Alpha Secondary Burnaby British Columbia Alton Public School Mississauga/Brampton Area Ontario Alvin Curling PS Toronto Ontario Annandale School Tillsonburg Ontario Annandale School Tillsonburg Ontario Annapolis Valley Regional Library -

Table of Contents

: : TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements i Executive Summary and Recommendations ii 1. Introduction 1 2. Literature Review 3 3. Methodology 8 4. Findings and Discussion: Primary Sources 10 4.1 Respondents’ Characteristics 11 4.2 Diabetes in the South Asian Population in Peel 17 4.3 Resources and Prevention Programming 33 4.4 Gaps and Barriers 45 4.5 Recommendations 49 5. Findings and Discussion: Secondary Sources 54 5.1 Socio-Economic Status of South Asians in Peel 55 5.2 Neighbourhood Characteristics by Diabetes Services 69 6. Conclusions and Recommendations 72 References 75 Appendices 78 Appendix 1: Qualitative Studies from 2005-2014 78 Appendix 2: Organizations of Key Informants 81 Appendix 3: Background on Socio-Economic Status & Related Indicators 82 3.1 Description and Size of the South Asian Population in Peel Neighbourhoods, 2006 82 3.2 Technical Notes 83 3.3 Definitions 85 3.4 Fact Sheet for the South Asian Population in Peel Region 87 Appendix 4: Potential Priority Peel Neighbourhoods by South Asian Population, Socio- 88 Economic Status of South Asians and Number of Diabetes Related Services Appendix 5: Research Team 89 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS St. Michael’s Hospital wishes to acknowledge the funding support of the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) for the production of this report. St. Michael’s Hospital thanks all the organizations, service providers, and community members who participated in and supported this important research study. Special thanks to Dr. Aisha Lofters, Scientist, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael's -

This Is My Thesis

ACCESS TO PRIMARY HEALTH CARE: DOES NEIGHBOURHOOD OF RESIDENCE MATTER? By Laura Bissonnette A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of Geography University of Toronto © Copyright by Laura Bissonnette (2009) Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-59301-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-59301-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Immunization of School Pupils

Immunization of School Pupils Act Estimated Coverage & Non-Medical Exemption Rates, By School 2018-19 School Year Immunization of School Pupils Act Estimated Coverage & Non-Medical Exemption Rates, By School 2018-19 School Year Summary This document summarizes the estimated coverage rates and non-medical exemption rates by school for Measles, Mumps, and Rubella vaccine (MMR) and for Diphtheria, Tetanus and Polio vaccines (DTP) for children attending school in the Region of Peel for the 2018-19 school year. Estimated coverage rates are not the same as immunization coverage rates. Overall for the 2018-19 school year: • the average estimated coverage rate across all Peel schools was 94.6% for MMR. • the average estimated coverage rate across all Peel schools was 90.8% for DTP. The difference in DTP rates compared to MMR (combined) is due to the additional requirement for an adolescent vaccine dose for diphtheria and tetanus. • the average non-medical exemption rates for MMR and for DTP were 1.8%. Background In Ontario, the Immunization of School Pupils Act (ISPA) requires children attending school to be vaccinated or have a valid exemption for the immunizations as described in Regulation 645. This legislation is important to protect children from vaccine preventable diseases and helps to decrease incidence of disease or outbreaks. Region of Peel – Public Health (‘Peel Public Health’) staff assess immunization records for one of the fastest growing populations in Ontario. Records for over 250,000 students, who attend a school located in the Region of Peel, are assessed every school year. According to the legislation, parents must provide records of immunization to public health; or if applicable, provide the necessary documentation for a medical or non-medical exemption (i.e. -

Liste Des Écoles Admissibles À La Subvention De Base Pour Les Écoles, Pour L’Année Scolaire 2016‐2017

Liste des écoles admissibles à la Subvention de base pour les écoles, pour l’année scolaire 2016‐2017 Mise à jour, septembre 2018 Ministère de l’Éducation Colonne 1 Colonne 2 Colonne 3 Colonne 4 Colonne 5 Colonne 6 Élément Numéro no Nom du conseil No du SIFE Nom de l'établissement Palier d'identification de BDICE l'école 1AlgomaDistrict School Board 24626 Adult Learning ELSS Secondaire 00200006 908010 2AlgomaDistrict School Board 00078 Anna McCrea PS Élémentaire 00200008 019186 3AlgomaDistrict School Board 00271 Arthur Henderson PS Élémentaire 00200053 067679 4AlgomaDistrict School Board 00174 Ben R McMullin PS Élémentaire 00200011 043362 5AlgomaDistrict School Board 00208 Blind River PS Élémentaire 00200012 054542 6AlgomaDistrict School Board 24624 Central Algoma Elementary School Élémentaire 00200045 285552 7AlgomaDistrict School Board 05206 Central Algoma SS Secondaire 00200045 891347 8AlgomaDistrict School Board 24241 Central Algoma SS (Intermediate) Élémentaire 00200045 137967 9AlgomaDistrict School Board 00379 Central Avenue PS Élémentaire 00200013 093548 10 Algoma District School Board 24336 Chapleau Elementary School Élémentaire 00200005 101214 11 Algoma District School Board 07609 Chapleau Secondary School Secondaire 00200005 900869 12 Algoma District School Board 00682 East View PS Élémentaire 00200015 161276 13 Algoma District School Board 00698 Echo Bay Central PS Élémentaire 00200016 165042 14 Algoma District School Board 05348 Elliot Lake SS (Sec) Secondaire 00200006 908010 15 Algoma District School Board 00589 Esten Park -

List of Schools Eligible for School Foundation Allocation for the 2016‐17 School Year

List of schools eligible for School Foundation Allocation for the 2016‐17 school year revised September 2018 Ministry of Education Column 1 Column 2 Column3 Column 4 Column5 Column6 Item No. School Identification Board Name SFIS No. Facility Name Panel BSID Number 1AlgomaDistrict School Board 24626 Adult Learning ELSS Secondary 00200006 908010 2AlgomaDistrict School Board 00078 Anna McCrea PS Elementary 00200008 019186 3AlgomaDistrict School Board 00271 Arthur Henderson PS Elementary 00200053 067679 4AlgomaDistrict School Board 00174 Ben R McMullin PS Elementary 00200011 043362 5AlgomaDistrict School Board 00208 Blind River PS Elementary 00200012 054542 6AlgomaDistrict School Board 24624 Central Algoma Elementary School Elementary 00200045 285552 7AlgomaDistrict School Board 05206 Central Algoma SS Secondary 00200045 891347 8AlgomaDistrict School Board 24241 Central Algoma SS (Intermediate) Elementary 00200045 137967 9AlgomaDistrict School Board 00379 Central Avenue PS Elementary 00200013 093548 10 Algoma District School Board 24336 Chapleau Elementary School Elementary 00200005 101214 11 Algoma District School Board 07609 Chapleau Secondary School Secondary 00200005 900869 12 Algoma District School Board 00682 East View PS Elementary 00200015 161276 13 Algoma District School Board 00698 Echo Bay Central PS Elementary 00200016 165042 14 Algoma District School Board 05348 Elliot Lake SS (Sec) Secondary 00200006 908010 15 Algoma District School Board 00589 Esten Park Public School Elementary 00200014 186783 16 Algoma District School Board -

23/9/2020 1/12 Prepared By: SHIVANGI AWASTHI, Administrator

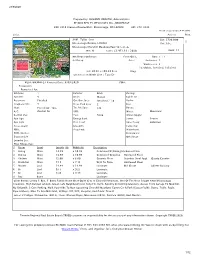

23/9/2020 Prepared by: SHIVANGI AWASTHI, Administrator RE/MAX REALTY SPECIALISTS INC., BROKERAGE 200-4310 Sherwoodtowne Blvd., Mississauga, ON L4Z4C4 905-272-3434 Printed on 09/23/2020 4:44:35 PM Links: Actions: Print 3881 Talias Cres List: $799,0 00 1 Mississauga Ontario L5M6L6 For: Sale Mississauga Churchill Meadows Peel 464-31-G SPIS: N Taxes: $3,953.39 / 2020 DOM: 14 Att/Row/Twnhouse Front On: E Rms: 7 + 1 2-Storey Acre: Bedrooms: 3 Washrooms: 3 1x2xMain, 1x4x2nd, 1x5x2nd Lot: 20.01 x 109.38 Feet Irreg: Dir/Cross St: Ninth Line / Tacc Dr 1 of 23 MLS#: W4904623 Contract Date: 9/09/2020 PIN#: Possession Remarks: Flex Kitchens: 1 Exterior: Brick Zoning: Fam Rm: Y Drive: Mutual Cable TV: Basement: Finished Gar/Gar Spcs: Attached / 1.0 Hydro: Fireplace/Stv: Y Drive Park Spcs: 2 Gas: Heat: Forced Air / Gas Tot Prk Spcs: 3.0 Phone: A/C: Central Air UFFI: Water: Municipal Central Vac: Pool: None Water Supply: Apx Age: Energy Cert: Sewer: Sewers Apx Sqft: Cert Level: Spec Desig: Unknown Assessment: GreenPIS: Farm/Agr: POTL: Prop Feat: Waterfront: POTL Mo Fee: Retirement: Elevator/Lift: Oth Struct: Laundry Lev: Phys Hdcap-Eqp: # Room Level Length (ft) Width (ft) Description 1 Living Main 14.99 x 10.99 Combined W/Dining Hardwood Floor 2 Dining Main 14.99 x 10.99 Combined W/Living Hardwood Floor 3 Kitchen Main 12.00 x 6.00 Ceramic Floor Stainless Steel Appl Quartz Counter 4 Breakfast Main 7.15 x 7.15 W/O To Patio Hardwood Floor 5 Master 2nd 14.99 x 14.99 Laminate W/I Closet Juliette Balcony 6 Br 2nd 9.15 x 9.25 Laminate 7 Br 2nd 9.48 x 9.18 Laminate 8 Rec Bsmt Laminate Client Remks: Lovely 3-Bed, 3-Baths Family Home On A Quiet Cres In Churchill Meadows, One Of The Most Sought After Mississauga Locations. -

Population, Demographics & Housing

City of Mississauga - Population, Demographics & Housing Mississauga • Ontario • Canada Population, Demographics & Housing This profile contains information on population, demographics, income and housing. Population Canada’s 10 Largest Municipalities – • The 2016 Census showed Canada’s population at 35,151,728 persons Mississauga is Canada’s 6th Largest City which amounted to an increase of 1,675,040 persons (5.0%) since the 2011 census. Canada’s 2011 population was 33,476,688. City Population • In 2016, nearly 24.9 million people, or more than seven-tenths of Toronto 2,731,571 Canadians, were living in census metropolitan area. Montreal 1,704,694 • Ontario’s 2016 population of 13,448,494, is an increase of more Calgary 1,239,220 than 596,600 more than the 12,851,821 reported in 2011 for a Ottawa 934,243 4.6% increase. Edmonton 932,546 • The Toronto Census Metropolitan Area (CMA) with a population of MISSISSAUGA 721,599 5,583,064 in 2011 grew 6.2% to 5,928,040 in 2016. Winnipeg 705,244 th Vancouver 631,486 • Mississauga; Canada’s 6 largest city; had a population increase of 1.1% from 2011 to 2016. Mississauga’s 2016 population of 721,599 Brampton 593,638 increased by 8,156 residents from 713,443 in 2011. Hamilton 536,917 rd Source: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census • Mississauga is Ontario’s 3 largest city surpassed only by the cities of Toronto and Ottawa. Updated July 2017 Connect with Mississauga Economic Development today. 1 1-800-456-2181 [email protected] View Print Exit City of Mississauga - Population, Demographics -

Proposed Route Network (2020)

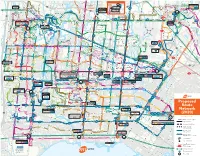

1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 R To/From ay vd Brampton Inset Map To/From Bramalea L Bl a n Bramalea Terminal Terminal t wso SSt R d a G GGateate DDr.r. w y v Lawson Blvd e r l A e MMavis o NNetherwoodetherwood A HHerefordereford d i RRd BBrandonrandon D B r Westwood Square vview a Steeles Ave g RRd To/From Sheridan d A t BBrandonrandon GGtt DDrr 16 v d e 16 i i t r College (Brampton) s e e RRd o d RRenaena RRdd 15 A l t d w TThamesgateh 7 11 15 a 61 407 amesgate 16 16 407 D Lisgar e a 38 r Brampton Gateway a R n r RRd g 15 30 d v SeeSee L y DDr d u GGate Dr S Slough Dr CCredit Dr AArgentiargen Rd R a tia Rd in d w a l 22 30 42 BramptonBrampton InsetInset MapMap n 110404 110707 32 38 MMeadowpine l o RRedstone 103 e R s o a w 401 d DDarcel Ave t a a rc e e el Ave s e u i e d 118585 i pap Rd forfforor contunuationccontinuation.ontunuation. h d S a k R l r c Hwy 407 & g s Rd t 38 d a s RRd a Milton Line s t o n a o h m AAr e i d o t t o FFinch w a 66 Sheridan College n Hurontario a i 427 d BBath Rd n GGoreway Dr r o a 22 n gentiag Rd p 61 S MMeadowvale Blvd MMississauga c n e d o d TTomken Rd e B e i R h B d SStt in St l CCatal n R v 407 Park & Ride d FFinancial a MManion T R t e 103 l r 61 66 ntari M D e AAve i Rd a KKimbel St r n d e a B v o t o W s o m CCactusactus GGateate BBlv a S a e i v R m w lv i m RRd g r l A 66 r d t n y n d e a n r 53 i a 19 a n 110404 i i t r r d r er Rd e b n B r i o BBrandon 32 a d r x g e o MMorning Star Dr R Hur u e t i d i BBramalea e DDrew Rd b e a A.M. -

Ontario Govern- It Is Much Bigger Than That

Specializing in residential high-rise concrete forming Overhead ITALFORM LIMITED Gate Protection 3 SIMPSON ROAD, BOLTON, ON L7E 1E4 TEL: (905) 857-8579 | FAX: (905) 857-9178 905 450-0500 ITALFORM www.italformlimited.com thefencepeople.com Daily Commercial News by Construct Connect® OCTOBER 22, 2018 www.dailycommercialnews.com VOL. 91 NO. 203 $5.23 plus HST OCOT shifting focus to Condos on Yorkville In Brief promotion of trades Oshawa named a Top 10 DON WALL contentious almost two years Intelligent Community STAFF WRITER after the former Liberal govern- OSHAWA, ONT. ntario College of Trades ment passed Bill 70 implementing The City of Oshawa has been (OCOT) registrar and OCOT reforms. included in the Intelligent Commu- OCEO George Gritziotis “The one thing people have to nity Forum’s (ICF) international rank- says after five years in existence remember, the College of Trades ing of the top intelligent communities it’s time for OCOT to finally start is a five-year-old organization and with populations between 100,000 and making progress on the full range when it opened its doors, it focused 250,000. of responsibilities within its man- on the regulatory piece,” Gritziotis, The list is the first of its kind and date and get past some of the con- now one year into his term with the latest in ICF’s By the Numbers troversial regulatory distractions OCOT, said in an interview after series. that have limited its effectiveness. his Building Trades address. “The ICF is a global movement of more OCOT was barely out of the gate reality is, when you look at the act, than 140 cities, towns and regions.