Vol. 16, No. 5 July 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hills of Dreamland

SIR EDWARD ELGAR (1857-1934) The Hills of Dreamland SOMMCD 271-2 The Hills of Dreamland Orchestral Songs The Society Complete incidental music to Grania and Diarmid Kathryn Rudge mezzo-soprano† • Henk Neven baritone* ELGAR BBC Concert Orchestra, Barry Wordsworth conductor ORCHESTRAL SONGS CD 1 Orchestral Songs 8 Pleading, Op.48 (1908)† 4:02 Song Cycle, Op.59 (1909) Complete incidental music to 9 Follow the Colours: Marching Song for Soldiers 6:38 1 Oh, soft was the song (No.3) 2:00 *♮ * (1908; rev. for orch. 1914) GRANIA AND DIARMID 2 Was it some golden star? (No.5) 2:44 * bl 3 Twilight (No.6)* 2:50 The King’s Way (1909)† 4:28 4 The Wind at Dawn (1888; orch.1912)† 3:43 Incidental Music to Grania and Diarmid (1901) 5 The Pipes of Pan (1900; orch.1901)* 3:46 bm Incidental Music 3:38 Two Songs, Op. 60 (1909/10; orch. 1912) bn Funeral March 7:13 6 The Torch (No.1)† 3:16 bo Song: There are seven that pull the thread† 3:33 7 The River (No.2)† 5:24 Total duration: 53:30 CD 2 Elgar Society Bonus CD Nathalie de Montmollin soprano, Barry Collett piano Kathryn Rudge • Henk Neven 1 Like to the Damask Rose 3:47 5 Muleteer’s Serenade♮ 2:18 9 The River 4:22 2 The Shepherd’s Song 3:08 6 As I laye a-thynkynge 6:57 bl In the Dawn 3:11 3 Dry those fair, those crystal eyes 2:04 7 Queen Mary’s Song 3:31 bm Speak, music 2:52 BBC Concert Orchestra 4 8 The Mill Wheel: Winter♮ 2:27 The Torch 2:18 Total duration: 37:00 Barry Wordsworth ♮First recordings CD 1: Recorded at Watford Colosseum on March 21-23, 2017 Producer: Neil Varley Engineer: Marvin Ware TURNER CD 2: Recorded at Turner Sims, Southampton on November 27, 2016 plus Elgar Society Bonus CD 11 SONGS WITH PIANO SIMS Southampton Producer: Siva Oke Engineer: Paul Arden-Taylor Booklet Editor: Michael Quinn Front cover: A View of Langdale Pikes, F. -

Louis Nicholas Song Collection

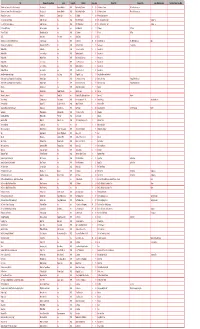

Title Composer/Arranger/Editor Lyricist Copyright Publisher Pages Box Original Title Translated Title Larger Work/Collection Translated Title of Large Work A Menina e a Cancao (Fillette et la Chanson, La) Villa-Lobos, H. Andrade, Mario de 1925 Max Eschig & Cie Edrs 12 25 A Menina e a Cancao Fillette et la Chanson, La A Menina e a Cancao (Fillette et la Chanson, La), c.2 Villa-Lobos, H. Andrade, Mario de 1925 Max Eschig & Cie Edrs 12 25 A Menina e a Cancao Fillette et la Chanson, La A Notre Dame sous-terre Chatillon, E. Chastel, Guy n/a E. Chatillon 7 30 A Notre Dame sous-terre A Te, O Cara, Amore Talora Bellini, Vincenzo n/a 1946 Pro Art Publications 4 29 A Te, O Cara, Amore Talora Puritans, The A Te, O Cara, Amore Talora, c.2 Bellini, Vincenzo n/a 1946 Pro Art Publications 4 29 A Te, O Cara, Amore Talora Puritans, The A Trianon (At Trianon) Holmes, Augusta n/a n/a Harch Music Co. 4 19 A Trianon At Trianon A Vous (To Thee) D'Hardelot and Boyer n/a 1895 G. Schirmer 4 17 A Vous To Thee A.B.C. Parry, John Parry, John n/a Oliver Ditson 5 23 A.B.C. Abborrita rivale, L' (She, My Rival Detested) Verdi, Giuseppe n/a 1915 G. Schirmer 10 28 Abborrita rivale, L' She, My Rival Detested Aida Abendsegen (Evening-Prayer) Humperdinck and Wette n/a 1894 B. Schott's Sohne 2 28 Abendsegen Evening-Prayer Abide with Me Ashford, E.L. -

≥ Elgar Sea Pictures Polonia Pomp and Circumstance Marches 1–5 Sir Mark Elder Alice Coote Sir Edward Elgar (1857–1934) Sea Pictures, Op.37 1

≥ ELGAR SEA PICTURES POLONIA POMP AND CIRCUMSTANCE MARCHES 1–5 SIR MARK ELDER ALICE COOTE SIR EDWARD ELGAR (1857–1934) SEA PICTURES, OP.37 1. Sea Slumber-Song (Roden Noel) .......................................................... 5.15 2. In Haven (C. Alice Elgar) ........................................................................... 1.42 3. Sabbath Morning at Sea (Mrs Browning) ........................................ 5.47 4. Where Corals Lie (Dr Richard Garnett) ............................................. 3.57 5. The Swimmer (Adam Lindsay Gordon) .............................................5.52 ALICE COOTE MEZZO SOPRANO 6. POLONIA, OP.76 ......................................................................................13.16 POMP AND CIRCUMSTANCE MARCHES, OP.39 7. No.1 in D major .............................................................................................. 6.14 8. No.2 in A minor .............................................................................................. 5.14 9. No.3 in C minor ..............................................................................................5.49 10. No.4 in G major ..............................................................................................4.52 11. No.5 in C major .............................................................................................. 6.15 TOTAL TIMING .....................................................................................................64.58 ≥ MUSIC DIRECTOR SIR MARK ELDER CBE LEADER LYN FLETCHER WWW.HALLE.CO.UK -

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst La Ttéiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’S Preludes for Piano Op.163 and Op.179: a Musicological Retrospective

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst la ttÉiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’s Preludes for Piano op.163 and op.179: A Musicological Retrospective (3 Volumes) Volume 1 Adèle Commins Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare 2012 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisors: Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley & Dr Patrick F. Devine Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to a number of people who have helped me throughout my doctoral studies. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors and mentors, Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Dr Patrick Devine, for their guidance, insight, advice, criticism and commitment over the course of my doctoral studies. They enabled me to develop my ideas and bring the project to completion. I am grateful to Professor Fiona Palmer and to Professor Gerard Gillen who encouraged and supported my studies during both my undergraduate and postgraduate studies in the Music Department at NUI Maynooth. It was Professor Gillen who introduced me to Stanford and his music, and for this, I am very grateful. I am grateful to the staff in many libraries and archives for assisting me with my many queries and furnishing me with research materials. In particular, the Stanford Collection at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University has been an invaluable resource during this research project and I would like to thank Melanie Wood, Elaine Archbold and Alan Callender and all the staff at the Robinson Library, for all of their help and for granting me access to the vast Stanford collection. -

St Stephens News XXI 18

St. Stephen's Traditional Episcopal Church, Timonium, Maryland Vol. XXI, Number 18 Edited by Anne Hawkins May 11th, 2010 FROM THE PARISH LIFE COMMITTEE how to put up the tents. Nor should we overlook the culi- nary skills of the chefs of the Silly Summer Suppers, Anne Hawkins and Charlotte Hawtin , who labored over hot The annual fete: What ovens baking the ever-popular pasties and sausage rolls (not to mention Welsh Cakes and brownies) for the event. a swell party it was! And we’d also be remiss if we failed to thank to all of IT WAS JUST the thing we needed to put the recession you – the parishioners of St. Stephen’s – who manned utterly out of our minds for a few hours! Indeed, our the stalls, and whose help and financial support contrib- British Garden Party and Fete – organized by Donna Sz- uted so greatly to the event’s success. per – has become much more that another fund raiser. Last but far from least, our thanks goes to Father John Like our Cookie Walk, it is rapidly achieving the status of Filkins, who travelled all the way from his parish in Pica- a much loved neighborhood institution. yune, Missisippi, to reprise his role as King Henry VIII, This year’s event seems set to become the best ever the distinguished royal personage who opened the garden both in terms of fun that was had and funds that were party. What a great sport he is! We only hope his new raised. The Tea Room, under the leadership of Rosa parishioners appreciate him as much as we do! Halbert, took in over $1,200. -

'The Crown of India' Masque: Reassessing Elgar and The

Mughals, Music, and “The Crown of India” Masque: Reassessing Elgar and the Raj published in South Asian Review 31.1 (November 2010): 13-36. Abstract Edward Elgar’s 1912 masque, “The Crown of India,” was written specifically for the music hall in celebration of the crowning of King George V and Queen Mary at the Delhi Durbar in 1911. This work has been addressed by musical and postcolonial scholars, and has been appropriated by two factions: those who wish to claim Elgar as an unrepentant imperialist, and see that manifested in this work, and those who wish to see him as a beacon for anti-imperialism, who see evidence of this in the cuts that he made to the libretto, written by Henry Hamilton. What has been lacking in this discourse is a vehicle to address those cuts from a literary perspective, citing actual support from the two versions of the libretto (with and without cuts). This paper will reassess the masque in light of these libretti, and offer a new assessment of Elgar’s imperial tendencies at that point in time, and the imperialism of the Raj. Article The Great Delhi Durbar of December 12, 1911, the third, final, and most spectacular of all the Imperial Durbars, was, according to all accounts, a spectacle of unheard-of opulence and extravagance. In it, King George V and Queen Mary were presented as Emperor and Empress of India, and, in their coronation robes, accepted presents from and the fealty of over 200 Indian princes. Amidst all the pomp, some matters of great import were decided at the Durbar. -

Vol. 18, No. 1 April 2013

Journal April 2013 Vol.18, No. 1 The Elgar Society Journal The Society 18 Holtsmere Close, Watford, Herts., WD25 9NG Email: [email protected] April 2013 Vol. 18, No. 1 Editorial 3 President Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM Julia Worthington - The Elgars’ American friend 4 Richard Smith Vice-Presidents Redeeming the Second Symphony 16 Sir David Willcocks, CBE, MC Tom Kelly Diana McVeagh Michael Kennedy, CBE Variations on a Canonical Theme – Elgar and the Enigmatic Tradition 21 Michael Pope Martin Gough Sir Colin Davis, CH, CBE Dame Janet Baker, CH, DBE Music reviews 35 Leonard Slatkin Martin Bird Sir Andrew Davis, CBE Donald Hunt, OBE Book reviews 36 Christopher Robinson, CVO, CBE Frank Beck, Lewis Foreman, Arthur Reynolds, Richard Wiley Andrew Neill Sir Mark Elder, CBE D reviews 44 Martin Bird, Barry Collett, Richard Spenceley Chairman Letters 53 Steven Halls Geoffrey Hodgkins, Jerrold Northrop Moore, Arthur Reynolds, Philip Scowcroft, Ronald Taylor, Richard Turbet Vice-Chairman Stuart Freed 100 Years Ago 57 Treasurer Clive Weeks The Editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, Secretary nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. Helen Petchey Front Cover: Julia Worthington (courtesy Elgar Birthplace Museum) Notes for Contributors. Please adhere to these as far as possible if you deliver writing (as is much preferred) in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. A longer version is available in case you are prepared to do the formatting, but for the present the editor is content to do this. Copyright: it is the contributor’s responsibility to be reasonably sure that copyright permissions, if Editorial required, are obtained. -

The Elgar Sketch-Books

THE ELGAR SKETCH-BOOKS PAMELA WILLETTS A MAJOR gift from Mrs H. S. Wohlfeld of sketch-books and other manuscripts of Sir Edward Elgar was received by the British Library in 1984. The sketch-books consist of five early books dating from 1878 to 1882, a small book from the late 1880s, a series of eight volumes made to Elgar's instructions in 1901, and two later books commenced in Italy in 1909.^ The collection is now numbered Add. MSS. 63146-63166 (see Appendix). The five early sketch-books are oblong books in brown paper covers. They were apparently home-made from double sheets of music-paper, probably obtained from the stock of the Elgar shop at 10 High Street, Worcester. The paper was sewn together by whatever means was at hand; volume III is held together by a gut violin string. The covers were made by the expedient of sticking brown paper of varying shades and textures to the first and last leaves of music-paper and over the spine. Book V is of slightly smaller oblong format and the sides of the music sheets in this volume have been inexpertly trimmed. The volumes bear Elgar's numbering T to 'V on the covers, his signature, and a date, perhaps that ofthe first entry in the volumes. The respective dates are: 21 May 1878(1), 13 August 1878 (II), I October 1878 (III), 7 April 1879 (IV), and i September 1881 (V). Elgar was not quite twenty-one when the first of these books was dated. Earlier music manuscripts from his hand have survived but the particular interest of these early sketch- books is in their intimate connection with the round of Elgar's musical activities, amateur and professional, at a formative stage in his career. -

Walton - a List of Works & Discography

SIR WILLIAM WALTON - A LIST OF WORKS & DISCOGRAPHY Compiled by Martin Rutherford, Penang 2009 See end for sources and legend. Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Catalogue No F'mat St Rel A BIRTHDAY FANFARE Description For Seven Trumpets and Percussion Completion 1981, Ischia Dedication For Karl-Friedrich Still, a neighbour on Ischia, on his 70th birthday First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Recklinghausen First 10-Oct-81 Westphalia SO Karl Rickenbacher Royal Albert Hall L'don 7-Jun-82 Kneller Hall G E Evans A LITANY - ORIGINAL VERSION Description For Unaccompanied Mixed Voices Completion Easter, 1916 Oxford First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel Hereford Cathedral 3.03 4-Jan-02 Stephen Layton Polyphony 01a HYP CDA 67330 CD S Jun-02 A LITANY - FIRST REVISION Description First revision by the Composer Completion 1917 First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel Hereford Cathedral 3.14 4-Jan-02 Stephen Layton Polyphony 01a HYP CDA 67330 CD S Jun-02 A LITANY - SECOND REVISION Description Second revision by the Composer Completion 1930 First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel St Johns, Cambridge ? Jan-62 George Guest St Johns, Cambridge 01a ARG ZRG -

Gloucester Cathedral Lay Clerks

GLOUCESTER CATHEDRAL ORGAN SCHOLARSHIP The Dean & Chapter of Gloucester Cathedral annually seek to appoint an organ scholar for each academic year. He/She will play a key role in the Cathedral music department, working closely with Adrian Partington (Director of Music), Jonathan Hope (Assistant Director of Music), Nia Llewelyn Jones (Singing Development Leader) and Helen Sims (Music Department Manager). The organ scholarship is open to recent graduates or to gap-year applicants of exceptional ability. Duties The organ scholar plays for Evensong every Tuesday, and in addition plays the organ or directs the choirs as necessary when the DoM or the ADoM is away. He/She will also play for many of the special services which take place in the Cathedral, for which additional fees are paid (see remuneration details below). The organ scholar is fully involved with the training of choristers and probationers and the teaching of theory and general musicianship. They will also be expected to help with the general administration of the music department, attending a weekly meeting and assisting other members of the department in the music office. Gloucester Cathedral Choir Today’s choir is the successor to the boys and monks of the Benedictine Abbey of St Peter, who sang for daily worship nine centuries ago. The choir of today stems from that established by Henry VIII in 1539, consisting of 18 choristers (who receive generous scholarships to attend the neighbouring King’s School), 12 lay clerks and choral scholars. The choir plays a major part in the internationally renowned Three Choirs Festival, the world’s oldest Music Festival, which dates back to 1715. -

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings of the Year 2019

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings Of The Year 2019 This is the seventeenth year that MusicWeb International has asked its reviewing team to nominate their recordings of the year. Reviewers are not restricted to discs they had reviewed, but the choices must have been reviewed on MWI in the last 12 months (December 2018-November 2019). The 128 selections have come from 27 members of the team and 65 different labels, the choices reflecting as usual, the great diversity of music and sources; I say that every year, but still the spread of choices surprises and pleases me. Of the selections, one has received three nominations: An English Coronation on Signum Classics and ten have received two nominations: Gounod’s Faust on Bru Zane Matthias Goerne’s Schumann Lieder on Harmonia Mundi Prokofiev’s Romeo & Juliet choreographed by John Cranko on C Major Marx’s Herbstymphonie on CPO Weinberg symphonies on DG Shostakovich piano works on Hyperion Late Beethoven sonatas on Hyperion Korngold orchestral works on Chandos Coates orchestral works on Chandos Music connected to Leonardo da Vinci on Alpha Hyperion was this year’s leading label with nine nominations, just ahead of C Major with eight. MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL RECORDING OF THE YEAR In this twelve month period, we published more than 2300 reviews. There is no easy or entirely satisfactory way of choosing one above all others as our Recording of the Year, but this year one recording in particular put itself forward as the obvious candidate. An English Coronation 1902-1953 Simon Russell Beale, Rowan Pierce, Matthew Martin, Gabrieli Consort; Gabrieli Roar; Gabrieli Players; Chetham’s Symphonic Brass Ensemble/Paul McCreesh rec. -

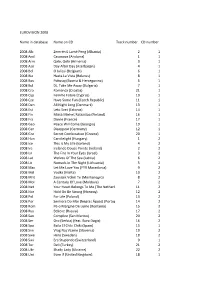

EUROVISION 2008 Name in Database Name on CD Track Number CD

EUROVISION 2008 Name in database Name on CD Track number CD number 2008 Alb Zemrën E Lamë Peng (Albania) 2 1 2008 And Casanova (Andorra) 1 1 2008 Arm Qele, Qele (Armenia) 3 1 2008 Aze Day After Day (Azerbaijan) 4 1 2008 Bel O Julissi (Belgium) 6 1 2008 Bie Hasta La Vista (Belarus) 8 1 2008 Bos Pokusaj (Bosnia & Herzegovina) 5 1 2008 Bul DJ, Take Me Away (Bulgaria) 7 1 2008 Cro Romanca (Croatia) 21 1 2008 Cyp Femme Fatale (Cyprus) 10 1 2008 Cze Have Some Fun (Czech Republic) 11 1 2008 Den All Night Long (Denmark) 13 1 2008 Est Leto Svet (Estonia) 14 1 2008 Fin Missä Miehet Ratsastaa (Finland) 16 1 2008 Fra Divine (France) 17 1 2008 Geo Peace Will Come (Georgia) 19 1 2008 Ger Disappear (Germany) 12 1 2008 Gre Secret Combination (Greece) 20 1 2008 Hun Candlelight (Hungary) 1 2 2008 Ice This Is My Life (Iceland) 4 2 2008 Ire Irelande Douze Pointe (Ireland) 2 2 2008 Isr The Fire In Your Eyes (Israel) 3 2 2008 Lat Wolves Of The Sea (Latvia) 6 2 2008 Lit Nomads In The Night (Lithuania) 5 2 2008 Mac Let Me Love You (FYR Macedonia) 9 2 2008 Mal Vodka (Malta) 10 2 2008 Mnt Zauvijek Volim Te (Montenegro) 8 2 2008 Mol A Century Of Love (Moldova) 7 2 2008 Net Your Heart Belongs To Me (The Netherlands) 11 2 2008 Nor Hold On Be Strong (Norway) 12 2 2008 Pol For Life (Poland) 13 2 2008 Por Senhora Do Mar (Negras Águas) (Portugal) 14 2 2008 Rom Pe-o Margine De Lume (Romania) 15 2 2008 Rus Believe (Russia) 17 2 2008 San Complice (San Marino) 20 2 2008 Ser Oro (Serbia) (feat.