Fifth Chapter the Interpretation of Tattvamasi and Its Significance In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vedanta in the West: Past, Present, and Future

Vedanta in the West: Past, Present, and Future Swami Chetanananda What Is Vedanta? Vedanta is the culmination of all knowledge, the sacred wisdom of the Indian sages, the sum of the transcendental experiences of the seers of Truth. It is the essence, or the conclusion, of the scriptures known as the Vedas. Because the Upanishads come at the end of the Vedas they are collectively referred to as Vedanta. Literally, Veda means "knowledge" and anta means "end." Vedanta is a vast subject. Its scriptures have been evolving for the last five thousand years. The three basic scriptures of Vedanta are the Upanishads (the revealed truths), the Brahma Sutras (the reasoned truths), and the Bhagavad Gita (the practical truths). Some Teachings from Vedanta Here are some teachings from the Upanishads: “Arise! Awake! Approach the great teachers and learn.” “Aham Brahmasmi.” [I am Brahman.] “Tawamasi.” [Thou art That.] “Sarvam khalu idam Brahma.” [Verily, everything is Brahman.] “Whatever exists in this changing universe is enveloped by God.” “If a man knows Atman here, he then aains the true goal of life.” “Om is the bow; the Atman is the arrow; Brahman is said to be the mark. It is to be struck by an undistracted mind.” “He who knows Brahman becomes Brahman.” “His hands and feet are everywhere. His eyes, heads, and mouths are everywhere. His ears are everywhere. He pervades everything in the universe.” “Speak the truth. Practise dharma. Do not neglect your study of the Vedas. Treat your mother as God. Treat your father as God. Treat your teacher as God. -

P. Vasundhara Rao.Cdr

ORIGINAL ARTICLE ISSN:-2231-5063 Golden Research Thoughts P. Vasundhara Rao Abstract:- Literature reflects the thinking and beliefs of the concerned folk. Some German writers came in contact with Ancient Indian Literature. They were influenced by the Indian Philosophy, especially, Buddhism. German Philosopher Arther Schopenhauer, was very much influenced by the Philosophy of Buddhism. He made the ancient Indian Literature accessible to the German people. Many other authors and philosophers were influenced by Schopenhauer. The famous German Indologist, Friedrich Max Muller has also done a great work, as far as the contact between India and Germany is concerned. He has translated “Sacred Books of the East”. INDIAN PHILOSOPHY IN GERMAN WRITINGS Some other German authors were also influenced by Indian Philosophy, the traces of which can be found in their writings. Paul Deussen was a great scholar of Sanskrit. He wrote “Allgemeine Geschichte der Philosophie (General History of the Philosophy). Friedrich Nieztsche studied works of Schopenhauer in detail. He is one of the first existentialist Philosophers. Karl Eugen Neuman was the first who translated texts from Pali into German. Hermann Hesse was also influenced by Buddhism. His famous novel Siddhartha is set in India. It is about the spiritual journey of a man (Siddhartha) during the time of Gautam Buddha. Indology is today a subject in 13 Universities in Germany. Keywords: Indian Philosophy, Germany, Indology, translation, Buddhism, Upanishads.specialization. www.aygrt.isrj.org INDIAN PHILOSOPHY IN GERMAN WRITINGS INTRODUCTION Learning a new language opens the doors of a different culture, of the philosophy and thinking of that particular society. How true it is in case of Indian philosophy having traveled to Germany years ago. -

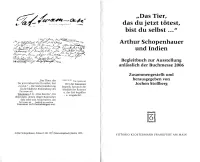

"Das Tier, Das Dujetzttötest, Bist Du Selbst Arthurschopenhauer Und

"Das Tier, das du jetzt tötest, bist du selbst Arthur Schopenhauer 4 und Indien Begleitbuch zur Ausstellung anlässlich der Buchmesse 2006 Zusammengestellt und "Das Thier, das Carica p 80 Tat-twam-asi herausgegeben von Du jetzt tödtest bist Du selbst, bist Wer das Tatgumes es - Jochen Stollberg jetzt." Die Seelenwanderung begreift, hat auch die ist die bildliche Einkleidung des Idealität des Raumes (Tat twam asi) u. der Zeit begriffen Tatoumes d. h. "Dies bist Du", für - u. umgekehrt. diejenigen, denen obiger Kantischer Satz oder sein Aequivalent, das Tat twam asi fasslich zu machen Tatoumes nicht beizubringen war. Arthur Schopenhauer, Foliant 2, Bi. 193r [Manuskriptbuchl Berlin 1826 VITTORIO KLOSTERMANN FRANKFURT AM MAIN Inhalt Klaus Ring Zum Geleit Matthias Koßler Grußwort Jochen Stollberg Arthur Schopenhauers Annäherung an die indische Welt 5 Urs App OUM - das erste Wort von Schopenhauers Lieblingsbuch 37 Urs App NICHTS - das letzte Wort von Schopenhauers Hauptwerk 51 Douglas L. Berger Erbschaften einer philosophischen Begegnung 61 Stephan Atzert Nirvana und Maya bei Schopenhauer 79 Heiner Feldhoff Und dann und wann ein weiser Elefant - Über Paul Deussens "Erinnerungen Indien" 85 Michael Gerhard Paul Deussen - Eine deutsch-indische Geistesbeziehung 101 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Arati Barua verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek of in India - Deutschen detaillierte bibliographische Daten Re-discovery Schopenhauer Nationalbibliographie; of the work and of sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Founding membership Indian branch of Schopenhauer Society 119 Thomas Frankfurter Bibliotheksschriften Regehly Schopenhauer und Siddharta 135 Herausgegeben von der Gesellschaft der Freunde der Stadt- und Universitätsbibliothek Frankfurt am Main e. -

Attitude of Vedanta Towards Religion

OSMANIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY q Author,' A b h e d n r: a n fl a . \v PPI 1 Title Attitude of veflnnta tovarfln This hook should be returned on or before the dale l;w marked below, SWAM1 ABHEDANANBA, aa apostle of Sri Ramakrishna Born October 2, 1866 Spent his early life among his brotherhood in Baranagar monastery near Calcutta, in severe austerity Travelled bare-footed all over India from 1888-1895 Acquainted with many distinguished savants including Prof. Max Mueller and Prof. Paul Deussen Landed inj&ew * 'tbtft the* charge of the Vedanta Society in 1897 Became with Prof. Rev. acquainted William ]ames / Dr. R. H. Newton, Prof. W. Jackson, Prof. Josiah Royce of Harvard/ Prof. Hyslop of Columbia, Prof. Lanmann, Prof. G. H. Howison, Prof. Fay, Mr. Edison, the inventor, Dr. Elmer Gates, Ralph Waldo Trine, W. D. Howells, Prof. Herschel C. Parker, Dr. H..S. Logan, Rev. Bishop Potter, Prof. Shaler Dr. James, the chairman of the Cambridge Philosophical Conference and the professors of Columbia, Harvard, Yale, Cornell, Berkeley and Clarke Universities Travelled extensively all through the United States, Canada, Alaska and Mexico Made frequent trips to Europe delivering lectures in different parts of the Continent Crossed the Atlantic for seventeen times Was appreciated very much for his profundity of intellectual scholarship, brilliance / oratorial talents, charming personality and nobility of character A short visit to India in 1906 Returned again to America Came back to India at last in 1921 On his way home joined the Educational Conference, Honolulu Visited Japan, China/ the Philipines, Singapore, Kualalumpur and Rangoon -Started on a long tour and went as far as Tibet -Established centres at Calcutta and Darjeeling Left his mortal frame on September 8, 1939. -

The Philosophy of the Vedanta in Its Relations to the Occidental Metaphysics by Dr

Adyar Pamphlets The Philosophy of the Vedanta in Its Relations... No. 136 The Philosophy of the Vedanta in Its Relations to the Occidental Metaphysics by Dr. Paul Deussen, Professor of Philosophy in the University of Kiel, Germany An address, delivered before the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Saturday the 25th February, 1893 Published in 1930 Theosophical Publishing House, Adyar, Chennai [Madras] India The Theosophist Office, Adyar, Madras. India [Page 1] ON my journey through India I have noticed with satisfaction, that in philosophy till now our brothers in the East have maintained a very good tradition, better perhaps, than the more active but less contemplative branches of the great Indo-Aryan family in Europe, where Empirism, Realism and their natural consequence, Materialism, grow from day to day more exuberantly, whilst metaphysics, the very center and heart of serious philosophy, are supported only by a few ones, who have learned to brave the spirit of the age. In India the influence of this perverted and pervasive spirit of our age has not yet overthrown in religion and philosophy the good traditions of the great ancient time. It is true, that most of the ancient darsanas even in India find only an historical interest; followers of the Sãnkhya-System occur rarely; Nyãya is cultivated mostly as an intellectual sport and exercise, like grammar or mathematics, but the Vedãntic is, now as in the ancient time living in the mind and heart of every thoughtful Hindu. It is true, that even here in the [Page 2] sanctuary of Vedãntic metaphysics, the realistic tendencies, natural to man, have penetrated, producing the misinterpreting variations of Shankara's Adwaita, known under the names Visishtãdwaita, Dwaita, Cuddhãdwaita of Rãmanuja, Mãdhva, Vallabha, but India till now has not yet been seduced by their voices, and of hundred Vedãntins (I have it from a well informed man, who is himself a zealous adversary of Shankara and follower of Rãmãnuja) fifteen perhaps adhere to Rãmãnuja, five to Madhva, five to Vallabha, and seventy-five to Shankarãchãrya. -

Translation Colloque V2.Indd

Convenors: CORINNE LEFÈVRE (CNRS) FABRIZIO SPEZIALE (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3) DECEMBER 8-9, 2016 CEIAS - 190 avenue de France 75013 Paris Rooms 638-641 The Fourth Perso-Indica Conference TRANSLATION AND THE LANGUAGES OF ISLAM: Indo-Persian tarjuma in a comparative perspective centre d’études - Inde | Asie du Sud centre for South Asian studies THE FOURTH PERSO-INDICA CONFERENCE Translation and the languages of Islam: Indo-Persian tarjuma in a comparative perspective On the occasion of the 4th international conference of the Perso-Indica project (http://www.perso-indica. net/), we would like to consider our main object of research—the Persian translations and original works bearing on Indic cultures—in a wider perspective than has generally been the case. We aim to do so by comparing the Indo-Persian movement of translation that took place in the subcontinent from the 13th century onwards with other processes of translations operating primarily from and to non-Muslim languages (e.g. Greek, Syriac, Pehlevi, Sanskrit into Arabic, etc.; Arabic into Latin; Greek into Ottoman Turkish, etc.) and, secondarily, between different languages of Muslim societies (e. g. Arabic into Persian, Turkish, Malay, Sub-Saharan languages, etc.; Persian into Urdu, Turkish, Malay, etc.). We have therefore invited contributions bearing on such movements of translation in different regions of the Muslim world between the 7th and 19th centuries, and highlighting the ways in which each specific translation process articulated the relation between source, -

Body, Illness and Medicine in Kolkata (Calcutta)

Digesting Modernity: Body, Illness and Medicine in Kolkata (Calcutta) S t e f a n M . E c k s London School of Economics and Political Science University of London Ph.D. Thesis Social Anthropology 2003 UMI Number: U615839 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615839 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 T H £ S F &! 62 Abstract This Ph.D. thesis presents an anthropological perspective on popular and professional concepts of the body in Kolkata (Calcutta), with special reference to ideas about the stomach/belly and the digestive system. By altering the routines and practices of daily life, changes brought about by modernization, globalization and urbanization are often associated with a decline of mental and physical well-being. In this context, the aim of this study is to juxtapose popular practices of self-care with professional views on illness and medicine. How do people in Kolkata perceive their bodies? How do they speak about health problems linked to digestion? What are the perceptions of health and illness among different medical professionals? How does this discourse reflect anxieties about the consequences of modernity in Kolkata? The data of this study are drawn from ethnographic fieldwork carried out between July 1999 and December 2000. -

Between Tradition and Modernity: Some Reflections on Professor A.K

DIALOGUE QUARTERLY Volume-17 No. 4 April-June, 2016 DIALOGUE QUARTERLY Editorial Advisory Board Mrinal Miri Jayanta Madhab Subscription Rates : For Individuals (in India) Editor Single issue Rs. 30.00 B.B. Kumar Annual Rs. 100.00 For 3 years Rs. 250.00 Consulting Editor J.N. Roy For Institutions: Single Issue Rs. 60.00 in India, Abroad US $ 15 Annual Rs. 200.00 in India, Abroad US $ 50 For 3 years Rs. 500.00 in India, Abroad US $ 125 All cheques and Bank Drafts (Account Payee) are to be made in the name of “ASTHA BHARATI”, Delhi. Advertisement Rates : Outside back-cover Rs. 25, 000.00 Per issue Inside Covers Rs. 20, 000.00 ,, Inner page coloured Rs. 15, 000.00 ,, Inner full page Rs. 10, 000.00 ,, Financial Assistance for publication received from Indian Council of ASTHA BHARATI Social Science Research. DELHI The views expressed by the contributors do not necessarily represent the view-point of the journal. Contents Editorial Perspective 7 Non-misplaced Concerns 1.North-East Scan 11 An Election Verdict That Created Waves Patricia Mukhim Will Assam Results Impact Other Congress Ruled NE States? 15 Pradip Phanjoubam © Astha Bharati, New Delhi 2. Between Tradition and Modernity: Some Reflections on Professor A.K. Saran’s Intellectual Sojourn 18 R.K. Misra Printed and Published by 3. Agyeya : The Ideal Poet-philosopher of Freedom 27 Dr. Lata Singh, IAS (Retd.) Ramesh Chandra Shah Secretary, Astha Bharati 4. Agyeya – Exploration into Freedom 36 Registered Office: Nandkishore Acharya 27/201 East End Apartments, 5. Romesh Chunder Dutt and Economic Analysis of Mayur Vihar, Phase-I Extension, India Under the British Rule 43 Delhi-110096. -

Securing-India.Pdf

Not for Sale THE CHINA–PAKISTAN NEXUS i Sale for Not Editorial Board Satish Chandra, IFS (Retd), former Deputy National Security Adviser Lt Gen Ravi Sawhney, PVSM, AVSM (Retd), former Deputy Chief of Army Staff Lt Gen Gautam Banerjee, PVSM, AVSM, YSM (Retd), former Chief of Staff, Central Command Ashok Kantha, IFS (Retd), former Ambassador to China and Secretary, Ministry of External Affairs Sale © VIF Vivekananda International Foundation 3 San Martin Marg, Chanakyapuri New Delhi-110021, India info@vifindia.org Follow us @VIFINDIA www.vifindia.org First published 2017 Photographs: pp 2, 46, 74, 93, 94, 122, 144, 157, 158: commons.wikimedia.org; p 1: narendramodi.in; p 20: vsmandal.org; p 36: mygov.in; p 57: 4gwar.wordpress.com,for Sergeant Tyler C Gregory; pp 58, 73: pmindia.gov.in; p 84: pbs.twimg.com; p 109: pbs.org; p 110: theindependentbd.com; p 134: moi.gov.mm; p 173: independent.co.uk; p 174: pulitzercenter.org; p 183: manoa.hawaii.edu; p 184: rocketstem.org, Bigelow Aerospace All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise—without the prior permission of the author/s and the publisher. ISBN 978-81-8328-510-0 Published by Wisdom Tree 4779/23, Ansari Road Darya Ganj, New Delhi-110Not 002 Ph.: 011-23247966/67/68 [email protected] Printed in India Contents Sale Preface v Strengthening India’s Nuclear Deterrence 2 General NC Vij, PVSM, UYSM, AVSM, and VIF Expert Group Swami Vivekananda’s -

Beyond the Dualism of Creature and Creator a Hindu-Christian

Beyond the Dualism of Creature and Creator A Hindu-Christian Theological Inquiry into the Distinctive Relation between the World and God Daniel John Soars Faculty of Divinity University of Cambridge This thesis is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Clare College August 2019 Preface This thesis is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my thesis has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the relevant Degree Committee. The text is 79,995 words long including footnotes but excluding bibliography. i Daniel John Soars, Clare College Beyond the Dualism of Creature and Creator: A Hindu-Christian Theological Inquiry into the Distinctive Relation between the World and God SUMMARY This thesis is one particular way of clarifying how the God Christians believe in is to be understood. The key conceptual argument which runs throughout the thesis is that the distinctive relation between the world and God in Christian theology is best understood as a non-dualistic one. -

The System of the Vedanta (Translation)

THE SYSTEM OF THE YEDANTA V ACCORDING TO BADAEAYANA'S BBAHMA-StoRAS AND QANKARA'S COMMENTARY THEREON SET FORTH AS A COMPENDIUM OE THE DOGMATICS OE BRAHMANISM FROM THE STANDPOINT OF QANKARA BY De. PAUL DEUSSEN FB0FEB80B OF FBIliOSO^HT, VIBL TTNlTBBfiITT AUTHOBIZED TEANSLATION CHARLES JOHNSTON BXnOAIi Omii SBBTICE, BBTIKES Ft! CHICAGO U. S. A. THE OPEN COURT PUBLISHING COMPANY 1912 ACKNOWLEDGMENT. The thanks of the Author and Translator are tendered to Dr. Paul Caeus, for his help in the Publication of this work; to Mr. B. T. Sturdey for valuable aid in revising the manuscript; and to Dr. J. Brune and Mr. Leopold Coevinus for help during the printing of the English version. Translator's Preface. My dear Professor Deussen, When, writing to me of your pilgrimage to India and your many friends in that old, sacred land, you suggested that I should translate Das System des Vedanta for them, and I most willingly consented, we had no thought that so long a time must pass, ere the completed book should see the light of day. Now that the period of waiting is ended, we rejoice together over the finished work. I was then, as you remember, in the Austrian Alps, seek- ing, amid the warm scented breath of the pine woods and the many-coloured beauty of the flowers, to drive from my veins the lingering fever of the Ganges delta, and steeping myself in the lore of the Eastern wisdom: the great Upanishads, the Bhagavad Oitd, the poems of Qankara, Master of Southern India. Your book brought me a new task, a new opportunity. -

Introduction

OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – REVISES, Wed Mar 12 2014, NEWGEN INTRODUCTION T e root of evil (in theology) is the confusion between the text and the word of God. J. S. Semler, Abhandlung von freier Untersuchung des Canon A HISTORY OF GERMAN INDOLOGY T is book investigates German scholarship on India between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries against the backdrop of its methodological self-understanding. It pursues this inquiry out of a wider interest in German philosophy of the same period, especially as concerns debates over scientif c method. T is twofold focus, that is, on the history of German Indology and on the idea of scientif c method, is deter- mined by the subject itself: because German Indology largely def ned itself in terms of a specif c method (the historical-critical method or the text-historical method), 1 1 . T e “historical-critical method” is a broad term for a method applied in biblical criti- cism. T e method sets aside the theological meaning of the Bible in favor of its historical context. T e method can be summed up as “understanding the Bible out of [the conditions of] its time.” (T e phrase is a common one, and used, for instance in both Tschackert’s article and as the title of Reventlow’s article; for both sources, see the third section of this chapter.) Within the conf nes of this method, scholars have developed and applied various techniques, such as literary criticism (Literaturkritik ), form criticism ( Formkritik ), tendency criticism ( Tendenzkritik ), and determining the history of transmission or of redaction(s) ( Überlieferungsgeschichte, Redaktionsgeschichte ) and of the text ( Textgeschichte ).