California State University, Northridge Teaching Jewish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Jewish Lived Experience in Cuba

THE JEWISH LIVED EXPERIENCE IN CUBA by DOROTHY DUGGAR FRANKLIN A DISSERTATION NATALIE ADAMS, CO-CHAIRPERSON UTZ MCKNIGHT, CO-CHAIRPERSON DIANNE BRAGG JERRY ROSENBERG KAREN SPECTOR Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2016 Copyright Dorothy Duggar Franklin 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This research utilized an interdisciplinary qualitative approach to inquiry that requires border-crossing as its methodology for discovery in order to fully understand the lived experience of the Jews of Cuba. The study included a deep read of the Jewish Diaspora with a starting point being 597 BCE, then followed thousands of years of waves and world-wide movements, eventually leading to those Jews who settled in Cuba. For access into the lives of the present-day Jews, interviews with four participants who represented a cross-section of the Cuban Hebrew community were conducted; visits to the synagogues and to the kosher butcher shop were made; and many trips to the Ashkenazi and the Sephardic cemeteries in Guanabacoa, Cuba, were also made in order to take photographs and personally visit the sites. The four respondents interviewed were English speakers, were over 20-years old, and were citizens of Cuba. They were asked identical questions via e-mail with follow-up correspondence. For other narrative resources, 19 unpublished recorded stories were transcribed and included in the study to gain further access into the lives of Cuba’s Jewish population. To complete the inquiry, one published narrative was used to show parallels between those who were interviewed, as well as to show the similarities to those voices from the unpublished group. -

Fulfillmenttheep008764mbp.Pdf

FULFILLMENT ^^^Mi^^if" 41" THhODOR HERZL FULFILLMENT: THE EPIC STORY OF ZIONISM BY RUFUS LEARSI The World Publishing Company CLEVELAND AND NEW YORK Published by The World Publishing Company FIRST EDITION HC 1051 Copyright 1951 by Rufus Learsi All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher, except for brief passages included in a review appearing in a newspaper or magazine. Manufactured in the United States of America. Design and Typography by Jos. Trautwein. TO ALBENA my wife, who had no small part in the making of this book be'a-havah rabbah FOREWORD MODERN or political Zionism began in 1897 when Theodor Herzl con- vened the First Zionist Congress and reached its culmination in 1948 when the State of Israel was born. In the half century of its career it rose from a parochial enterprise to a conspicuous place on the inter- national arena. History will be explored in vain for a national effort with roots imbedded in a remoter past or charged with more drama and world significance. Something of its uniqueness and grandeur will, the author hopes, flow out to the reader from the pages of this narrative. As a repository of events this book is not as inclusive as the author would have wished, nor does it make mention of all those who labored gallantly for the Zionist cause across the world and in Pal- estine. Within the compass allotted for this work, only the more significant events could be included, and the author can only crave forgiveness from the actors living and dead whose names have been omitted or whose roles have perhaps been understated. -

ED057706.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 057 706 rt. 002 042 AWTMOR Moskowitz, Solomon TITLP Hebrew for 'c,econlAty Schools. INSTTTUTIOW Wew York State Education Dept., Albany. Pureau of Secondary Curriculum !Development. IMB DAT!!! 71 wOTE 143n. EDRS PRICE XF-30.65 HC-$6.56 DESCRIPTOPS Articulation (Program); Audiolingual skills; Sasic Skills; Bibliographies; Cultural Education: Hebrew; Language Instruction; Language Laboratories; Language Learning Levels; Language Programs; Language skills; Lesson Plans; Manuscript Writing (Handlettering); Pattern Drills (Language); Secondary Schools; *Semitic Languages; *Teaching Guides ABSTRACT This teacher's handbook for Hebrew instruction in secondary Schools, designed for use in public schools, is patterned after New York state Education Department handbooks for French, seanieho and German* Sections include:(1) teaching the four skills, (2) speaking,(3) audiolingual experiences,(4) suggested content and topics for audioLingual experiences, (15) patterns for drill,(6) the toxtbook in audiolingual presentation, (7) language laboratories, (0) reading and writing,(9) culture,(10) articulation, (11) vocabulary, (12) structures for four- and six-year sequences,(13) the Hebrew alphabet,(14) model lessons-- grades 10 and 11, and (15) student evaluation. A glossary, bibliography, and appendix illustrating Hebrew calligraphy are included. (m) HEBREW For Secondary Schools U DISPANTNENT Of NIA1.11N. wsurang EDUCATION OfFICE OF EDUCATION HOS DOCUNFOCI HAS SUN ExACTLy As mom MIA SKINSOOUCED onsouganoft ottroutkvotoYH PERsON op vim o OeusNONS STATEDsT mon or wows Nipasturfr Offs Cut.00 NOT NECES lumps+ Poo/no% OR PoucvOFFICE OF f DU The University of the State of New York THE STATE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT Bureau of Secondary Curriculum Development/Albany/1971 1 THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Regents of the University (with years when terms expire) 1984 Joseph W. -

Handbook on Judaica Provenance Research: Ceremonial Objects

Looted Art and Jewish Cultural Property Initiative Salo Baron and members of the Synagogue Council of America depositing Torah scrolls in a grave at Beth El Cemetery, Paramus, New Jersey, 13 January 1952. Photograph by Fred Stein, collection of the American Jewish Historical Society, New York, USA. HANDBOOK ON JUDAICA PROVENANCE RESEARCH: CEREMONIAL OBJECTS By Julie-Marthe Cohen, Felicitas Heimann-Jelinek, and Ruth Jolanda Weinberger ©Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, 2018 Table of Contents Foreword, Wesley A. Fisher page 4 Disclaimer page 7 Preface page 8 PART 1 – Historical Overview 1.1 Pre-War Judaica and Jewish Museum Collections: An Overview page 12 1.2 Nazi Agencies Engaged in the Looting of Material Culture page 16 1.3 The Looting of Judaica: Museum Collections, Community Collections, page 28 and Private Collections - An Overview 1.4 The Dispersion of Jewish Ceremonial Objects in the West: Jewish Cultural Reconstruction page 43 1.5 The Dispersion of Jewish Ceremonial Objects in the East: The Soviet Trophy Brigades and Nationalizations in the East after World War II page 61 PART 2 – Judaica Objects 2.1 On the Definition of Judaica Objects page 77 2.2 Identification of Judaica Objects page 78 2.2.1 Inscriptions page 78 2.2.1.1 Names of Individuals page 78 2.2.1.2 Names of Communities and Towns page 79 2.2.1.3 Dates page 80 2.2.1.4 Crests page 80 2.2.2 Sizes page 81 2.2.3 Materials page 81 2.2.3.1 Textiles page 81 2.2.3.2 Metal page 82 2.2.3.3 Wood page 83 2.2.3.4 Paper page 83 2.2.3.5 Other page 83 2.2.4 Styles -

Everything You Need to Know About Shabbat Services

Everything You Need to Know About Shabbat Services By: Jane E. Herman, Union for Reform Judaism Introduction Shabbat, the Jewish Sabbath, is a weekly holiday that celebrates creation and offers a respite from the hectic pace of the rest of the week. Shabbat begins at sundown on Friday and ends with Havdalah—a short ceremony that separates Shabbat from the rest of the week—on Saturday evening. Many Jewish communities hold Shabbat services on both Friday night and Saturday morning (and sometimes also on Friday afternoon and on Saturday afternoon and evening). Each congregation is autonomous, although many are linked by their denominational affiliation. Reform congregations in North America are members of the Union for Reform Judaism. Although each Shabbat worship service differs from the others (and every congregation does things its own way), there are some Shabbat customs, traditions, and practices observed in one form or another in synagogues and Jewish communities throughout the world. Whether you attend services on Friday night or Saturday morning (or both), rarely, sometimes or often, these are some of the things you may see or hear in and around the synagogue (also known as a temple or a shul, which is a Yiddish word and often is used interchangeable with the other two). Outside the Building Although some congregations request the presence of local police officers or employ private security personal as a precaution at the door, anyone—regardless of belief or religion is welcome at worship services. Some congregations have outdoor worship space, where services may be held when the weather is warm. -

Torah Binders

WOMEN’S LEAGUE FOR CONSERVATIVE JUDAISM International Day of Study Leader’s Guide: Torah Binders HISTORY Jerusalem scribes probably began to inscribe the Torah as a scroll of parchment during the first century C.E. The early scrolls were generally wrapped around a single stave, but by the 4th century, the Torah scrolls had become large enough to require two staves to support their bulk. (The stave is called an etz hayim.) The size of the scroll made it necessary to use a binder to hold the rolled scroll together while being moved. The binder also served as a girdle to keep the Torah from unrolling or tearing.1 In the Diaspora, the Torah binders of the Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews developed distinctive characteristics. The Ashkenazi Wimpel The first instance of a recorded observation of the use of a fabric binder for the rolled Torah is found in a German text from 1530 entitled, Der Gantze Judische Glaube (The Entire Jewish Faith) written by Antonius Margaritha, son of Rabbi Jacob Margolot of Regensburg, Germany. Margaritha identifies these binders as mappen (mappot) for synagogues. He writes: “They are very beautiful and some are embroidered with the name of the child, when he was born and circumcised.”2 Joseph Yuspa Hahn of Frankfurt (1570-1637) in writing about the Torah binder (mitpakhat) called it a “wimpel.” The wimpel was generally made from the swaddling cloth of the male child on which he had rested during his brit milah (ritual circumcision). After the brit milah, the cloth of linen was washed and pieced to create a continuous band. -

Jerusalem Rabbinate Charged with Political Perversion Papal Protest A

.. ******* *** *** *****1*****5- DIGI T 029 06 22~9 11/30/88 ** 33 R. I: JEWISH HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION Inside: Local News, pages 2.3 130 SESS l ONS ST. Opinion, page 4 PROVIDENCE, RI 02906 Around Town, page 8 THE ONLY ENGLISH-JEWISH WEEKLY IN R.I. AND SOUTHEAST MASS. , VOLUME LXXV, NUMBER 35 THURSDAY, JULY 28, 1988 35¢ PER COPY Jerusalem Rabbinate Charged Papal Protest With Political Perversion The removal of the Kashrut was "the hostel is affiliated with a at the hostel after the certificaton certification of the United Syna Movement that undermines Ju had been revoked. gogue of America"s youth hostel in daism," and, "in our eyes destroys Rabbi Epstein expressed rus Israel by the Jerusalem ultra the Jewish religion." He further gratitude to Rabbi Louis Bern Orthodox Rabbinate has been stated that issuing a Kashrut cer stein and other leaders of the challenged in legal proceedings tificate to a Conservative institu American Orthodox community filed by the United synagogue of tion was similar to issuing it to a for supporting the Conservative America. "monastery." Responding, mr. movement in trus dispute. On Friday morning prior to Kreutzer indicated that, trus sec "Issues of politics, not piety are Tisha B"Av eve, a Jewish day of ond class citizensrup for Conser controlling the Jerusalem Rab ntional mourning, Franklin D. vative Jews would not be tolerated binate," calimed Franklin D. Kreutzer, International Presi and that the ultra-Orthodox Jew Kreutzer, International Presi dent of the United Synagogue of ish Rabbinate was involving itself dent of the United Synagogue of Americ and Rabbi Jerome M. -

IMAGINING INDEPENDENCE PARK by Oren Segal a Dissertation

IMAGINING INDEPENDENCE PARK by Oren Segal A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Near Eastern Studies) In the University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Shachar M Pinsker, Chair Professor David M. Halperin Associate Professor Carol Bardenstein Assistant Professor Maya Barzilai “Doing it in the park, Doing it after Dark, oh, yeah” The Blackbyrds, “Rock Creek Park,” City Life (Fantasy Records, 1975) © Oren Segal All rights reserved 2012 In memory of Nir Katz and Liz Troubishi ii Acknowledgements Most of all, I would like to thank my committee members: Shachar Pinsker, David Halperin, Carol Bardenstein, and Maya Barzilai. They are more than teachers to me, but mentors whose kindness and wisdom will guide me wherever I go. I feel fortunate to have them in my life. I would also like to thank other professors, members of the Jean and Samuel Frankel Center for Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan, who were and are part of my academic and personal live: Anita Norich, Deborah Dash Moore, Julian Levinson, Mikhail Krutikov, and Ruth Tsoffar. I also wish to thank my friends and graduate student colleagues who took part in the Frankel Center’s Reading Group: David Schlitt, Ronit Stahl, Nicholas Block, Daniel Mintz, Jessica Evans, Sonia Isard, Katie Rosenblatt, and especially Benjamin Pollack. I am grateful for funding received from the Frankel Center throughout my six years in Ann Arbor; without the center’s support, this study would have not been possible. I would also like to thank the center’s staff for their help. -

The Image and the Idea Syllabus (PDF)

THE IMAGE AND THE IDEA An Interdisciplinary Seminar on Art History and Jewish Thought ARTS 5074 C / Fall 2020 Stern College for Women / Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought Rabbi Meir Soloveichik and Professor Jacob Wisse Professor Rabbi Meir Soloveichik E-mail: [email protected] Professor Jacob Wisse E-mail [email protected] Course Abstract As beings rooted in a physical world governed by laws of nature, we achieve sanctity through tangible and sensory means: acts of charity, song, prayer, text study – and art. At the same time, the Tanakh and Talmud express persistent concern lest we give in to the human temptation to render the Divine in finite form. This interdisciplinary course explores the process through which art and artists make use of physical means to achieve spiritual or intangible ends; and the ways Judaism and Jewish sources deal with the tension between the physical and the spiritual, between external act and internal meaning, between the visual and the intellectual, the image and the idea. Course Structure In each section of the course, we will pair images, paintings, sculptures and architecture with readings from art history, philosophy and Jewish thought. We will begin by addressing the question of art in religion in general and in Judaism in particular; we will then turn to specific traditions, and utilizing both essays and objects within local museum collections, including Yeshiva University Museum, explore the tension and complex relationship between beauty and spirituality, between appreciating extraordinary aesthetic quality and fulfilling religious ideals. We will also hear from visiting scholars, rabbis, artists, art historians and curators, who will address the subject under discussion at different stages in the course. -

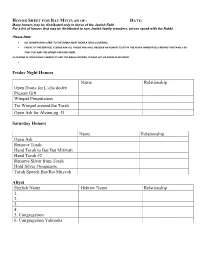

Honor Sheet Form for 2 Torahs

HONOR SHEET FOR BAT MITZVAH OF: DATE: Many honors may be distributed only to those of the Jewish Faith For a list of honors that may be distributed to non Jewish family members, please speak with the Rabbi Please Note: • ALL WOMEN WHO COME TO THE BIMAH MUST WEAR A HEAD COVERING. • PRIOR TO THE SERVICE, PLEASE ASK ALL THOSE WHO WILL RECEIVE AN HONOR TO SIT IN THE ROWS IMMEDIATELY BEHIND THE FAMILY SO THAT YOU AND THE USHER CAN FIND THEM. IF ANYONE IN YOUR FAMILY NEEDS TO USE THE BIMAH ACCESS, PLEASE LET US KNOW IN ADVANCE. • Friday Night Honors Name Relationship Open Doors for L’cha dodee Present Gift Wimpel Presentation Tie Wimpel around the Torah Open Ark for Aleinu pg. 51 Saturday Honors Name Relationship Open Ark Remove Torah Hand Torah to Bar/Bat Mitzvah Hand Torah #2 Remove Silver from Torah Hold Silver Ornaments Torah Speech Bar/Bat Mitzvah Aliyot English Name Hebrew Name Relationship 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Congregation 6. Congregation Yahrzeits 7. Parents Hagbah Lifting 1st Torah Gelilah 1st Torah Dressing the Torah Maftir Hagbah 2nd Torah Gelilah 2 Speech 2, Haftorah, Candy (limited to 25 pieces), Speech 3 Ashrei Open Ark for Return of Torah (pg. 153) Carry Torah #1 for return to Ark Carry Torah #2 for return to Ark Ain Kelohanu Open Ark for Aleinu; pg. 183 – Aleinu Synagogue Presentation Rabbi Minyonaires Presentation HAMC Presentation Rabbi Parent Blessing Including Release Prayer Motzi For Bima Announcements: Where are guests coming from? Names of: Grandparents, Siblings? Other details for your Bar/Bat Mitzvah celebration - eg. -

Herzl's Jewish Journey

Ü Sonderausgabe 2010 B E R 110 1897 ILLUSTRIERTE 2007 JAHRE GEGRÜNDET 1897 VON THEODOR HERZL Theodor Herzl 150th Birthday 2. 5. 1860 3. 7. 1904 e should all just convert to enough to from his "a new blossoming of the Jewish spirit." Christianity.” A student giving turn him into fraternity for During his visit to Palestine in 1898, he Wthis answer to a teacher asking a Jewish anti- standing up arrived in Jerusalem late on a Friday. how to solve the problem of anti-Semitism hero, there is Herzl’s against its anti- Though ill and suffering from exhaustion, would undoubtedly be dismissed as a smart- declaration that in the Semitic tendencies. he nevertheless walked the great distance aleck. new state he envisioned, "We When he had yet to establish to his hotel so as not to contravene the laws Even if his name was Theodor Herzl? shall keep our rabbis within the confines of himself as a writer, he refused the offer of of the Sabbath. Whatever other This, in fact, is precisely how the their synagogues…” a prominent editor in Vienna to publish his considerations may have influenced him, visionary of the Jewish state first thought But to portray Herzl as anything other manuscript if he would only agree to adopt this decision also evidences a growing to put an end to the phenomenon: "In than an ardent defender of the Jewish faith a pen name less Jewish than his own. And respect for Jewish tradition that fully broad daylight, at twelve o'clock on a with a deep affinity to the Land of Israel even his plan for mass conversion would matured by the time he published Sunday, the exchange of faith would take would be to do him a terrible injustice, involve only the very young, thus making Altneuland in 1902. -

Herzl Day Vs. International Herzl Day

Herzl Day vs. International Herzl Day By Jerry Klinger Four years ago, June 29, 2004, with belated awareness that Ben Gurion was wrong, that Zionism is not infused in the heart and soul by simply living in Israel, the Knesset passed the Herzl Law. It is an extraordinary admission by the government of Israel that the why of the existence of the State is in danger of being lost. The law created the Herzl Council empowered to recommend, institute and encourage learning about Herzl's vision. On the 10th of Iyar throughout Israel, in the schools, the army and communities, the what of Herzl's vision, the why of Israel, is to be taught and commemorated. Less than 50% of Israelis and even less than that of Israeli school children have more than a passing recognition of Herzl. Growing numbers of military inductees do not even know who Herzl was. How can a society exist if it does not know why it exists? The intent of the Herzl law is to change the tide. Stephen Theodore Norman was the last descendent of Theodor Herzl. He was his grandson. Stephen was the only Herzl, other than Theodor, to visit Palestine, love the land, the people and to be an ardent Zionist. Stephen was a Captain in the British army during WWII. After a brief tantalizing visit to Palestine, to see what his grandfather had started, he wrote in his diary on his way back to Britain for discharge. "I had been told, you will be amazed at Jewish youth in Palestine: They are fair and sturdy and handsome.