Radio Broadcasting and New Information and Communication Technologies: Uses, Challenges and Prospects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TS 101 499 V2.2.1 (2008-07) Technical Specification

ETSI TS 101 499 V2.2.1 (2008-07) Technical Specification Digital Audio Broadcasting (DAB); MOT SlideShow; User Application Specification European Broadcasting Union Union Européenne de Radio-Télévision EBU·UER 2 ETSI TS 101 499 V2.2.1 (2008-07) Reference RTS/JTC-DAB-57 Keywords audio, broadcasting, DAB, digital, PAD ETSI 650 Route des Lucioles F-06921 Sophia Antipolis Cedex - FRANCE Tel.: +33 4 92 94 42 00 Fax: +33 4 93 65 47 16 Siret N° 348 623 562 00017 - NAF 742 C Association à but non lucratif enregistrée à la Sous-Préfecture de Grasse (06) N° 7803/88 Important notice Individual copies of the present document can be downloaded from: http://www.etsi.org The present document may be made available in more than one electronic version or in print. In any case of existing or perceived difference in contents between such versions, the reference version is the Portable Document Format (PDF). In case of dispute, the reference shall be the printing on ETSI printers of the PDF version kept on a specific network drive within ETSI Secretariat. Users of the present document should be aware that the document may be subject to revision or change of status. Information on the current status of this and other ETSI documents is available at http://portal.etsi.org/tb/status/status.asp If you find errors in the present document, please send your comment to one of the following services: http://portal.etsi.org/chaircor/ETSI_support.asp Copyright Notification No part may be reproduced except as authorized by written permission. -

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

Replacing Digital Terrestrial Television with Internet Protocol?

This is a repository copy of The short future of public broadcasting: Replacing digital terrestrial television with internet protocol?. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/94851/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Ala-Fossi, M and Lax, S orcid.org/0000-0003-3469-1594 (2016) The short future of public broadcasting: Replacing digital terrestrial television with internet protocol? International Communication Gazette, 78 (4). pp. 365-382. ISSN 1748-0485 https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048516632171 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ The Short Future of Public Broadcasting: Replacing DTT with IP? Marko Ala-Fossi & Stephen Lax School of Communication, School of Media and Communication Media and Theatre (CMT) University of Leeds 33014 University of Tampere Leeds LS2 9JT Finland UK [email protected] [email protected] Keywords: Public broadcasting, terrestrial television, switch-off, internet protocol, convergence, universal service, data traffic, spectrum scarcity, capacity crunch. -

A Brief History of Radio Broadcasting in Africa

A Brief History of Radio Broadcasting in Africa Radio is by far the dominant and most important mass medium in Africa. Its flexibility, low cost, and oral character meet Africa's situation very well. Yet radio is less developed in Africa than it is anywhere else. There are relatively few radio stations in each of Africa's 53 nations and fewer radio sets per head of population than anywhere else in the world. Radio remains the top medium in terms of the number of people that it reaches. Even though television has shown considerable growth (especially in the 1990s) and despite a widespread liberalization of the press over the same period, radio still outstrips both television and the press in reaching most people on the continent. The main exceptions to this ate in the far south, in South Africa, where television and the press are both very strong, and in the Arab north, where television is now the dominant medium. South of the Sahara and north of the Limpopo River, radio remains dominant at the start of the 21St century. The internet is developing fast, mainly in urban areas, but its growth is slowed considerably by the very low level of development of telephone systems. There is much variation between African countries in access to and use of radio. The weekly reach of radio ranges from about 50 percent of adults in the poorer countries to virtually everyone in the more developed ones. But even in some poor countries the reach of radio can be very high. In Tanzania, for example, nearly nine out of ten adults listen to radio in an average week. -

Mass Media in the USA»

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by BSU Digital Library Mass Media In The USA K. Khomtsova, V. Zavatskaya The topic of the research is «Mass media in the USA». It is topical because mass media of the United States are world-known and a lot of people use American mass media, especially internet resources. The subject matter is peculiarities of different types of mass media in the USA. The aim of the survey is to study the types of mass media that are popular in the USA nowadays. To achieve the aim the authors fulfill the following tasks: 1. to define the main types of mass media in the USA; 2. to analyze the popularity of different kinds of mass media in the USA; 3. to mark out the peculiarities of American mass media. The mass media are diversified media technologies that are intended to reach a large audience by mass communication. There are several types of mass media: the broadcast media such as radio, recorded music, film and tel- evision; the print media include newspapers, books and magazines; the out- door media comprise billboards, signs or placards; the digital media include both Internet and mobile mass communication. [4]. In the USA the main types of mass media today are: newspapers; magazines; radio; television; Internet. NEWSPAPERS The history of American newspapers goes back to the 17th century with the publication of the first colonial newspapers. It was James Franklin, Benjamin Franklin’s older brother, who first made a news sheet. -

Digital Audio Broadcasting : Principles and Applications of Digital Radio

Digital Audio Broadcasting Principles and Applications of Digital Radio Second Edition Edited by WOLFGANG HOEG Berlin, Germany and THOMAS LAUTERBACH University of Applied Sciences, Nuernberg, Germany Digital Audio Broadcasting Digital Audio Broadcasting Principles and Applications of Digital Radio Second Edition Edited by WOLFGANG HOEG Berlin, Germany and THOMAS LAUTERBACH University of Applied Sciences, Nuernberg, Germany Copyright ß 2003 John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England Telephone (þ44) 1243 779777 Email (for orders and customer service enquiries): [email protected] Visit our Home Page on www.wileyeurope.com or www.wiley.com All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England, or emailed to [email protected], or faxed to (þ44) 1243 770571. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the Publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. -

Research on the Safe Broadcasting of Television Program

MATEC Web of Conferences 63, 04002 (2016) DOI: 10.1051/matecconf/20166304002 MMME 2016 Research on the Safe Broadcasting of Television Program Jin Bao SONG1,a, Jin Hong SONG2 and Jian Ping CHAI1 1Information Engineering School, Communication University of China, Beijing, China 2Shandong Gold Mining Jiaojia Gold Mine (Laizhou) co.,LTD Abstract. The existing way of broadcasting and television monitoring has a lot of problems in China. On the basis of the signal technical indicators monitoring in the present broadcasting and television monitoring system, this paper further extends the function of the monitoring network in order to broaden the services of monitoring business and improve the effect and efficiency of monitoring work. The problem of identifying video content and channel in television and related electronic media is conquered at a low cost implementation way and the flexible technology mechanism. The coverage for video content and identification of the channel is expanded. The informative broadcast entries are generated after a series of video processing. The value of the numerous broadcast data is deeply excavated by using big data processing in order to realize a comprehensive, objective and accurate information monitoring for the safe broadcasting of television program. 1 Introduction paper is the development of cheap monitoring hardware devices which can be widely deployed to the village, so The existing way of broadcasting and television the actual situation of the user terminal broadcasting can monitoring has a lot of problems in China. Firstly, the be monitored by the administration of radio, film and existing way of monitoring is the front-end monitoring television. -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

History of Radio Broadcasting in Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1963 History of radio broadcasting in Montana Ron P. Richards The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Richards, Ron P., "History of radio broadcasting in Montana" (1963). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5869. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5869 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HISTORY OF RADIO BROADCASTING IN MONTANA ty RON P. RICHARDS B. A. in Journalism Montana State University, 1959 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1963 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate School Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number; EP36670 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Oiuartation PVUithing UMI EP36670 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

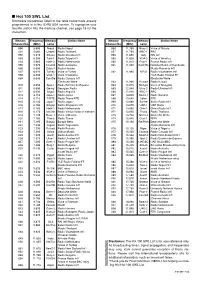

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

American Forces Network Radio Programming Decisions (D-2006-117)

September 27, 2006 Information Technology Management American Forces Network Radio Programming Decisions (D-2006-117) Department of Defense Office of Inspector General Quality Integrity Accountability Additional Copies To obtain additional copies of this report, visit the Web site of the Department of Defense Inspector General at http://www.dodig.mil/audit/reports or contact the Secondary Reports Distribution Unit at (703) 604-8937 (DSN 664-8937) or fax (703) 604-8932. Suggestions for Future Audits To suggest ideas for or to request future audits, contact the Office of the Deputy Inspector General for Auditing at (703) 604-8940 (DSN 664-8940) or fax (703) 604-8932. Ideas and requests can also be mailed to: ODIG-AUD (ATTN: Audit Suggestions) Department of Defense Inspector General 400 Army Navy Drive (Room 801) Arlington, VA 22202-4704 Acronyms AFIS American Forces Information Service AFN American Forces Network AFRTS American Forces Radio and Television Service AFN-BC American Forces Network - Broadcast Center ASD(PA) Assistant Secretary of Defense (Public Affairs) OIG Office of Inspector General Department of Defense Office of Inspector General Report No. D-2006-117 September 27, 2006 (Project No. D2006-D000FI-0103.000) American Forces Network Radio Programming Decisions Executive Summary Who Should Read This Report and Why? This report will be of interest to DoD personnel responsible for the selection and distribution of talk-radio programming to overseas U.S. Forces and their family members and military personnel serving onboard ships. The report discusses the controls and processes needed for establishing a diverse inventory of talk-radio programming on American Forces Network Radio. -

Radio Broadcasting

Programs of Study Leading to an Associate Degree or R-TV 15 Broadcast Law and Business Practices 3.0 R-TV 96C Campus Radio Station Lab: 1.0 of Radiologic Technology. This is a licensed profession, CHLD 10H Child Growth 3.0 R-TV 96A Campus Radio Station Lab: Studio 1.0 Hosting and Management Skills and a valid Social Security number is required to obtain and Lifespan Development - Honors Procedures and Equipment Operations R-TV 97A Radio/Entertainment Industry 1.0 state certification and national licensure. or R-TV 96B Campus Radio Station Lab: Disc 1.0 Seminar Required Courses: PSYC 14 Developmental Psychology 3.0 Jockey & News Anchor/Reporter Skills R-TV 97B Radio/Entertainment Industry 1.0 RAD 1A Clinical Experience 1A 5.0 and R-TV 96C Campus Radio Station Lab: Hosting 1.0 Work Experience RAD 1B Clinical Experience 1B 3.0 PSYC 1A Introduction to Psychology 3.0 and Management Skills Plus 6 Units from the following courses (6 Units) RAD 2A Clinical Experience 2A 5.0 or R-TV 97A Radio/Entertainment Industry Seminar 1.0 R-TV 03 Sportscasting and Reporting 1.5 RAD 2B Clinical Experience 2B 3.0 PSYC 1AH Introduction to Psychology - Honors 3.0 R-TV 97B Radio/Entertainment Industry 1.0 R-TV 04 Broadcast News Field Reporting 3.0 RAD 3A Clinical Experience 3A 7.5 and Work Experience R-TV 06 Broadcast Traffic Reporting 1.5 RAD 3B Clinical Experience 3B 3.0 SPCH 1A Public Speaking 4.0 Plus 6 Units from the Following Courses: 6 Units: R-TV 09 Broadcast Sales and Promotion 3.0 RAD 3C Clinical Experience 3C 7.5 or R-TV 05 Radio-TV Newswriting 3.0