The Role of Climatic Factors in Determining Tourist Satisfaction: the Case of Five Indian Ocean Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comoro Archipelago

GROUP STRUCTURE AND ACTIVITY RHYTHM IN LEMUR MONGOZ (PRIMATES, LEMURIFORMES) ON ANJOUAN AND MOHELI ISLANDS, COMORO ARCHIPELAGO IAN TATTERSALL VOLUME 53: PART 4 ANTHROPOLOGICAL PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY NEW YORK :1976 4 .4.4.4.4 .4.4 4.4.4 .4.4 4.4 - . ..4 ..4.4.4 o -Q ¼' 11 I, -_7 Tf., GROUP STRUCTURE AND ACTIVITY RHYTHM IN LEMUR MONGOZ (PRIMATES, LEMURIFORMES) ON ANJOUAN AND MOHELI ISLANDS, COMORO ARCHIPELAGO IAN TATTERSALL Associate Curator, Department ofAnthropology TheAmerncan Museum ofNatural History VOLUME 53: PART 4 ANTHROPOLOGICAL PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY NEW YORK: 1976 ANTHROPOLOGICAL PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY Volume 53, Part 4, pages 367-380, figures 1-6, tables 1, 2 Issued December 30, 1976 Price. $1.1 5 ISSN 0065-9452 This Part completes Volume 53. Copyright i The American Museum of Natural History 1976 ABSTRACT A previous study in Madagascar revealed the day. This difference appears to be environ- Lemur mongoz to be nocturnal and to exhibit mentally linked. Further, on Anjouan L. mongoz pair-bonding. Subsequent work in the Comoro Is- exhibits pair-bonding and the formation of lands has shown that, whereas in the warm, "family" groups, but on Moheli there is variation seasonal lowland areas of Moheli and Anjouan L. in group structure. It is possible that group com- mongoz is likewise nocturnal, in the humid high- position of L. mongoz on Moheli undergoes lands of Anjouan these animals are active during seasonal change. RItSUMI! Une premiere etude de Lemur mongoz de jour. -

UNION DES COMORES Unité – Solidarité – Développement

UNION DES COMORES Unité – Solidarité – Développement --------- ! DIRECTION GENERALE DE L’ANACEP ---------- _________________________________________________ PROJET DE FILETS SOCIAUX DE SECURITES Accord de Financement N° D0320 -KM RAPPORT SEMESTRIEL D’ACTIVITES N° 05 Période du 1 er juillet au 31 décembre 2017 Février 2018 1 SIGLES ET ABREVIATIONS ACTP : Argent Contre Travail Productif ACTC : Argent Contre Travail en réponses aux Catastrophes AG : Assemblée Générale AGEX : Agence d’Exécution ANACEP : Agence Nationale de Conception et d’Exécution des Projets AGP : Agence de Paiement ANO: Avis de Non Objection AVD : Agent Villageois de Développement ANJE : Amélioration du Nourrisson et du Jeune Enfant BE : Bureau d’Etudes BM : Banque Mondiale CCC : Comité Central de Coordination CG : Comité de Gestion CGES : Cadre de Gestion Environnementale et Sociale CGSP : Cellule de Gestion de Sous Projet CI : Consultant Individuel CP : Comité de Pilotage CPR : Cadre de politique de Réinstallation CPS Comité de Protection Sociale CR : Comité Régional DAO : Dossier d’appel d’offre DEN : Directeur Exécutif National DGSC : Direction Générale de la Sécurité Civile DP : Demande de Proposition DER : Directeur Exécutif Régional DNO : Demande de Non Objection DSP : Dossier de sous- projet FFSE : Facilitateur chargé du Suivi Evaluation HIMO : Haute Intensité de Main d’Œuvres IDB : Infrastructure de Bases IDB C : Infrastructure De Base en réponse aux Catastrophes IEC : Information Education et Communication MDP : Mémoire Descriptif du Projet MWL : île de Mohéli -

KASHKA 60.Qxd

www.kashkazi.com 600 fc / 3,50 euros kashkazi numéro 60 - février 2007 les vents n’ont pas de frontière, l’information non plus notre dossier Depuis des décennies, le Nyumakele est le symbole de la pauvreté aux Comores. Le plateau nyumakele anjouanais, au coeur de la problématique foncière, fournit l’essentiel des migrants de l’archipel. la poudrière L’explosion est-elle inévitable ? de l’archipel enquête à ndzuani ça s’passe comme ça, à “bacar-land” une île de plus en plus verrouillée l’action trouble des réseaux la liberté de la presse menacée ÉCONOMIE Qui sont les investisseurs arabes TENSIONS POLICIÈRES Les raisons de l’escalade à Maore POLITIQUE Oili : “Le statut de DOM est un échec” maore la “guerre des sexes” Andil Saïd, un habitant est déclarée de Sandapoini (LG) Ndzuani, Ngazidja, Mwali : 600 fc / Maore : 3,50 euros / Réunion, France : 4,50 euros / Madagascar : 2.500 ariary kashkazi Participez à l’indépendance de votre journal ABONNEZ-VOUS L’abonnement est un soutien indispensable à la presse indépendante. Kashkazi est un journal totalement indépendant. Son financement dépend essentiellement de ses ventes. L’abonnement est le meilleur moyen pour le soutenir, et participer à l’indépendance de sa rédaction. C’est aussi l’assurance de le recevoir chaque premier jeudi du mois chez soi. LES TARIFS (pour 1 an, 12 numéros) Mwali, Ndzuani, Ngazidja / particuliers : 8.000 fc / administrations, entreprises : 12.000 fc Maore / particuliers : 40 euros / administrations, entreprises : 60 euros COMMENT S’ABONNER (+ de renseignements au 76 17 97 -Moroni- ou au 02 69 21 93 39 -Maore-) Mwali, Ndzuani, Ngazidja / envoyez vos nom, prénom, adresse et n° de téléphone + le paiement à l’ordre de BANGWE PRODUCTION à l’adresse suivante : KASHKAZI, BP 5311 Moroni, Union des Comores Maore, La Réunion / envoyez nom, prénom, adresse et n° de téléphone + le paiement à l’ordre de RÉMI CARAYOL à l’adresse suivante : Nicole Gellot, BP 366, 97615 Pamandzi 2 kashkazi 60 février 2007 EN PRÉAMBULE sommaire (60) Ça s’passe comme ça, 4 ENTRE NOUS LE JOURNAL DES LECTEURS DES NOUVELLES DE.. -

Dian053-2011.Pdf

ASSEMBLÉE NATIONALE CONSTITUTION DU 4 OCTOBRE 1958 TREIZIÈME LÉGISLATURE _____________________________________________________ R A P P O R T D’ I N F O R M A T I O N Présenté à la suite de la mission effectuée en du 2 au 11 octobre 2010 par une délégation du (1) GROUPE D’AMITIÉ FRANCE- UNION DES COMORES _____________________________________________________ (1) Cette délégation était composée de M. Daniel Goldberg, Président, MM. Loïc Bouvard et Bernard Lesterlin. – 3 – SOMMAIRE CARTE...........................................................................................................................5 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................7 I. PRESENTATION DES COMORES.................................................................11 A. LES COMORES EN CHIFFRES ................................................................................11 B. REPERES GEOGRAPHIQUES ..................................................................................12 1. Situation........................................................................................................12 2. Le climat .......................................................................................................13 3. Les îles ..........................................................................................................13 a. Ngazidja............................................................................................................. 13 b. Anjouan ............................................................................................................ -

Draft Management Plan 110823

Northern Marine Reserves (Riviere Banane, Anse aux Anglais, Grand Bassin, Passe Demi), Rodrigues Draft Management Plan 2011-2016 v1 1 Executive Summary [To be completed] 2 Northern Marine Reserves (Riviere Banane, Anse aux Anglais, Grand Bassin, Passe Demi), Rodrigues Draft Management Plan 2011-2016 v1 Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 2 Prologue .......................................................................................................................................... 6 3 Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... 7 4 Background ..................................................................................................................................... 8 4.1 Justification for the Marine Reserves ....................................................................................... 8 4.1.1 Where were we? ............................................................................................................... 8 4.1.2 Where are we? .................................................................................................................. 9 4.1.3 Where do we want to go? ................................................................................................. 9 4.1.4 What is the best way to do what we need to do? ............................................................. 9 -

Cave and Karst Management in Australasia 17 Buchan, Victoria, 2007 105

Grande Caverne - a new show cave for Rodrigues, Mauritius Greg Middleton Abstract given to the use of state-of-the-art large 24 volt LED arrays. Complex lighting control systems The caves of the calcareous aeolianite of will be avoided in favour of a simple South-West Rodrigues (Mauritius, Indian physically-switched system which can be Ocean) have been known since at least 1786 serviced by local personnel. when the first bones of the extinct, flightless solitaire were collected from them. One cave, Current planning would have the giant tortoise Caverne Patate, has been operated as a show and cave park open about late-July 2007. cave for a very long time and, since flaming torches were used for lighting until 1990, has suffered considerably from soot deposits. Most The island of Rodrigues of its accessible speleothems have been The island of Rodrigues is situated in the souvenired. Indian Ocean about 600 km east of Mauritius In 2001 Mauritian/Australian naturalist and – and 5,000 km west of Australia. It is 108 sq. entrepreneur, Owen Griffiths, conceived of a km in area – a little bigger than Maria Island (a project to restore the native vegetation of part part-karst national park off the east coast of of the aeolianite plain of SW Rodrigues, Tasmania with a permanent population of reintroduce giant tortoises to the site and about 5) and has a population of around provide visitor access to the underlying caves. 40,000. The direct depredations of humans In due course a lease of nearly 20 hectares was and the progressive removal of much of the obtained from the Rodrigues administration, a island‟s natural vegetation since people first new company, François Leguat Ltd, was settled there in 1691 (North-Coombes 1971) established to run the project and a program to has led to the extinction of much of the breed the necessary tortoises was commenced endemic fauna, especially the birds and on Mauritius. -

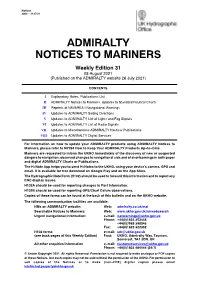

Weekly Edition 31 of 2021

Notices 3062 -- 3147/21 ADMIRALTY NOTICES TO MARINERS Weekly Edition 31 05 August 2021 (Published on the ADMIRALTY website 26 July 2021) CONTENTS I Explanatory Notes. Publications List II ADMIRALTY Notices to Mariners. Updates to Standard Nautical Charts III Reprints of NAVAREA I Navigational Warnings IV Updates to ADMIRALTY Sailing Directions V Updates to ADMIRALTY List of Lights and Fog Signals VI Updates to ADMIRALTY List of Radio Signals VII Updates to Miscellaneous ADMIRALTY Nautical Publications VIII Updates to ADMIRALTY Digital Services For information on how to update your ADMIRALTY products using ADMIRALTY Notices to Mariners, please refer to NP294 How to Keep Your ADMIRALTY Products Up--to--Date. Mariners are requested to inform the UKHO immediately of the discovery of new or suspected dangers to navigation, observed changes to navigational aids and of shortcomings in both paper and digital ADMIRALTY Charts or Publications. The H--Note App helps you to send H--Notes to the UKHO, using your device’s camera, GPS and email. It is available for free download on Google Play and on the App Store. The Hydrographic Note Form (H102) should be used to forward this information and to report any ENC display issues. H102A should be used for reporting changes to Port Information. H102B should be used for reporting GPS/Chart Datum observations. Copies of these forms can be found at the back of this bulletin and on the UKHO website. The following communication facilities are available: NMs on ADMIRALTY website: Web: admiralty.co.uk/msi Searchable Notices to Mariners: Web: www.ukho.gov.uk/nmwebsearch Urgent navigational information: e--mail: [email protected] Phone: +44(0)1823 353448 +44(0)7989 398345 Fax: +44(0)1823 322352 H102 forms e--mail: [email protected] (see back pages of this Weekly Edition) Post: UKHO, Admiralty Way, Taunton, Somerset, TA1 2DN, UK All other enquiries/information e--mail: [email protected] Phone: +44(0)1823 484444 (24/7) Crown Copyright 2021. -

Coastal Construction and Destruction in Times of Climate Change on Anjouan, Comoros Beate M.W

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Electronic Publication Information Center Natural Resources Forum 40 (2016) 112–126 DOI: 10.1111/1477-8947.12102 Considering the locals: coastal construction and destruction in times of climate change on Anjouan, Comoros Beate M.W. Ratter, Jan Petzold and Kamardine Sinane Abstract The current discussion of anticipated climate change impacts and future sea level rise is particularly relevant to small island states. An increase in natural hazards, such as floods and storm waves, is likely to have a devastating impact on small islands’ coastlines, severely affecting targeted sustainable development. Coastal erosion, notably human- induced erosion, has been an ongoing threat to small island biodiversity, resources, infrastructure, and settlements, as well as society at large. In the context of climate change, the problem of coastal erosion and the debate surrounding it is gaining momentum. Before attributing associated impacts to climate change, current human activities need to be analysed, focusing not only on geomorphological and climatological aspects, but also on political and traditional cul- tural frameworks. The objective of this paper is to demonstrate the importance of the social-political-ecological systems analysis for adaptation strategies, and thus for future sustainable development. Coastal use is based on human con- structs of the coast, as well as local perceptions and values ascribed to the coast. We use the case study of Anjouan, Comoros to differentiate between constructive and destructive practices on the coast, from both a mental and technical perspective. Beach erosion is described as more than a resource problem that manifests itself locally rather than nationally. -

Les Comores, Une Destination En Devenir Touristique

CONFERENCE DES BAILLEURS DE FONDS EN FAVEUR DES COMORES Ile Maurice, le 8 décembre 2005 Les Comores, une destination en devenir touristique DOCUMENT CADRE STRATEGIE TOURISTIQUE 1 « La tradition rapportée depuis la nuit des temps raconte que le roi Salomon et la reine Bilqis de Saba (appelée Sada au Yémen septentrionale) ont passé leur voyage de noces sur l’île de Ngazidja. Eperdument amoureux, le couple a escaladé le volcan Karthala et la reine jeta sa bague dans le cratère, promettant de revenir un jour sur ces lieux magiques et aux paysages lunaires. Aucun guide ne peut présenter les Comores aussi bien que par cette légende immuable. » Ahmed Ali Amir, Le Tourisme : un secteur promoteur, Agence Comorienne de Presse, 25 octobre 2005 2 TABLE DES MATIERES Introduction 6 Carte générale de situation des Comores 7 Fiche d’identité de l’Union des Comores 8 1- ELEMENTS DE CADRAGE 9 1.1 La Conférence des Partenaires des Comores : vers des pistes concrètes de développement économique 9 1.1.1 Contexte politique et économique local 9 1.1.1.1 Un nouveau cadre institutionnel pour l’archipel des Comores 9 1.1.1.2 Une économie encore fragile 9 1.1.2 Vers une stratégie de réduction de la pauvreté 10 1.1.3 La Conférence des partenaires : un consensus pour poser les bases d’un développement économique 11 1.2 Un contexte touristique mondial, régional et local favorable pour l’Union des Comores 12 1.2.1 Poids et perspectives de l’industrie touristique mondiale 12 1.2.1.1 Les arrivées internationales dans le monde depuis 1950 12 1.2.1.2 Les recettes du tourisme -

Observations of Seiching and Tides Around the Islands of Mauritius and Rodrigues

Western IndianOBSERVATI Ocean J.ONS Mar. OF SSci.EICHING Vol. 7,& T No.IDES 1, AR pp.OUND 15–28, THE ISLANDS 2008 OF MAURITIUS & RODRIGUES 15 © 2008 WIOMSA Observations of Seiching and Tides Around the Islands of Mauritius and Rodrigues R. Lowry1, D. T. Pugh2, E. M. S. Wijeratne3 1Mauritius Oceanography Institute, DPI, Western Australia; 2National Oceanography Centre, Southampton, UK, Proudman Oceanographic Laboratory, Merseyside, UK; 3Oceanography Division, NARA, Sri Lanka. Keywords: Seiching, tides, Mauritius, Rodrigues, Indian Ocean Abstract—Short-period sea level changes around the islands of Mauritius and Rodrigues in the central Indian Ocean have been analysed to determine the favoured seiche periods. The largest amplitudes are found inside the harbours of Port Louis, Mauritius (7 and 20 minutes) and Port Mathurin, Rodrigues (25 minutes), but these amplitudes are much smaller just outside the harbours, and the characteristic periods are found only locally, confirming that local topography controls the periods of the seiching. The extent and energising of these seiching phenomena calls for further investigation. Associated seiche currents, potentially much stronger than tidal currents, could influence harbour shipping movements. Analysis of the sea level data showed that there are significant spatial variations in the amplitudes and phases of the tides around Mauritius Island, but the around-island tidal variations are much smaller for Rodrigues Island. INTRODUCTION southeast of the Seychelles main island group. At Aldabra, periods from 25 to 50 minutes were Seiching is the oscillation of bodies of water recorded, intermittently from October to May, at natural periods, controlled by the depth and when they persisted from two to 14 days. -

Rodrigues.Pdf

Rodrigues Overview: Rodrigues is the main outer island of the Republic of Mauritius. Rodrigues obtained its autonomy in 2002. The Rodriguan economy is based on a subsistence type of agriculture, stock rearing and fishing. Territory: Total Land Area: Surface area of 108 sq. km EEZ: 1.2 million square km Location: Rodrigues is situated in the Indian Ocean approximately 560 km to the North East of Mauritius, which is itself 800 km East of Madagascar. Latitude and Longitude: 19 42 S and 63 25 E Time Zone: GMT +4 Total Land Area: 108 EEZ: 1200000 Climate: Moderate climate. Average annual temperature between 14 and 29 degrees Celsius. Natural Resources: Marine red and green algae. There are several species of endemic tropical flora and fauna. ECONOMY: Total GDP: Per Capita GDP: % of GDP per Sector: Primary Secondary Tertiary % of Population Employed by Sector Primary Secondary Tertiary External Aid/Remittances: Data unavailable Growth: The Rodriguan economy is predominantly based on a subsistence type of agriculture, stock rearing, and fishing. The major livestock reared are cattle, sheep, pigs, goats, and poultry. Total livestock production not only meets the subsistence requirements of the island but also generates surplus for export to Mauritius. Labour Force: 2001 21,723 2002 22,289 Unemployment Year: Unemployment Rate (% of pop.) 2000 9.6% 2001 13% 2002 13.5% Industry: Major industrial employers are found in the fields of public administration & defence, agriculture, forestry, fishing, manufacturing, and construction. Other important employers are found in transportation, storage & communication, education, and hotels & restaurants. The manufacturing sector is limited to a few enterprises, namely stone crushing, baking, metal works, woodwork, garment making, shoe making and small agro- industries. -

Janvier 2019 PROJET DE RENCORCEMENT DES CAPACITES INSTITUTIONNELLES (PRCI II) - COMORES Plan D’Aménagement Et De Développement Touristique ______

Projet de Renforcement des Capacités Institutionnelles (PRCI) - PhaseII APPUI AU COMMISSARIAT GÉNÉRAL AU PLAN POUR (I) L’ÉLABORATION D’UNE STRATÉGIE FONCIÈRE, (II) POUR LA FORMULATION D’UNE STRATÉGIE DE DÉVELOPPEMENT DU TOURISME, ET (III) POUR L’ÉLABORATION D’UNE ÉTUDE DIAGNOSTIQUE ET UNE STRATÉGIE DE DÉVELOPPEMENT DU SECTEUR PRIVÉ PLAN D’AMÉNAGEMENT ET DE DÉVELOPPEMENT TOURISTIQUE PRÉSENTÉ PAR LE GROUPEMENT : Quartier Point E, Rue 2 Villa N°9B B.P. 23 714 Dakar-Ponty (Sénégal) Tel : + 221 33 824 9060 Email : [email protected] Janvier 2019 PROJET DE RENCORCEMENT DES CAPACITES INSTITUTIONNELLES (PRCI II) - COMORES Plan d’aménagement et de développement touristique _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ INFORMATIONS SUR LE DOCUMENT TABLEAU DE DIFFUSION Destinataire Objet Diffusion Paraphe Entité Fonction on RC RF A I Nom PRCI Coordonnateur x x x x RC : Revue Contenu – RF : Revue Forme – A : Application – I : Information TABLE DE L’HISTORIQUE DU DOCUMENT Paragraphes et Création ou objet Version Date Auteur pages concernés de la mise à jour Elhadj Malick MBAYE, Expert International en Tourisme 3.04 31-01-2019 Toutes les pages Version finale Sitti ATTOUMANI, Experte Nationale en Tourisme REMARQUE Chaque révision du présent document doit correspondre à un numéro de version dont le format est : X.YY Où X : est le numéro de version Y : est le numéro de mise à jour de la version (indice de révision) Une version nouvelle correspond à une modification majeure du contenu. Cette décision est prise lors de validation sur proposition de(s) l’auteur(s). PROJET DE RENCORCEMENT DES CAPACITES INSTITUTIONNELLES (PRCI II) - COMORES Plan d’aménagement et de développement touristique _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE DES MATIERES 1 LES CHOIX POLITIQUES ............................................................................................................................