Borderline Gender Ed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

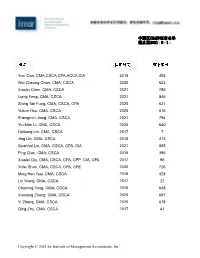

中国区cma持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日

中国区CMA持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日 Yixu Cao, CMA,CSCA,CPA,ACCA,CIA 2019 492 Wai Cheung Chan, CMA, CSCA 2020 622 Xiaolin Chen, CMA, CSCA 2021 785 Liang Feng, CMA, CSCA 2021 845 Shing Tak Fung, CMA, CSCA, CPA 2020 621 Yukun Hsu, CMA, CSCA 2020 676 Shengmin Jiang, CMA, CSCA 2021 794 Yiu Man Li, CMA, CSCA 2020 640 Huikang Lin, CMA, CSCA 2017 7 Jing Lin, CMA, CSCA 2018 415 Quanhui Liu, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CIA 2021 855 Ping Qian, CMA, CSCA 2018 396 Xiaolei Qiu, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CFP, CIA, CFA 2017 96 Yufei Shan, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CFE 2020 726 Ming Han Tsai, CMA, CSCA 2018 428 Lin Wang, CMA, CSCA 2017 22 Chunling Yang, CMA, CSCA 2020 648 Xiaolong Zhang, CMA, CSCA 2020 697 Yi Zhang, CMA, CSCA 2020 678 Qing Zhu, CMA, CSCA 2017 41 Copyright © 2021 by Institute of Management Accountants, Inc. 中国区CMA持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日 Siha A, CMA 2020 81134 Bei Ai, CMA 2020 84918 Danlu Ai, CMA 2021 94445 Fengting Ai, CMA 2019 75078 Huaqin Ai, CMA 2019 67498 Jie Ai, CMA 2021 94013 Jinmei Ai, CMA 2020 79690 Qingqing Ai, CMA 2019 67514 Weiran Ai, CMA 2021 99010 Xia Ai, CMA 2021 97218 Xiaowei Ai, CMA, CIA 2019 75739 Yizhan Ai, CMA 2021 92785 Zi Ai, CMA 2021 93990 Guanfei An, CMA 2021 99952 Haifeng An, CMA 2021 92781 Haixia An, CMA 2016 51078 Haiying An, CMA 2021 98016 Jie An, CMA 2012 38197 Jujie An, CMA 2018 58081 Jun An, CMA 2019 70068 Juntong An, CMA 2021 94474 Kewei An, CMA 2021 93137 Lanying An, CMA, CPA 2021 90699 Copyright © 2021 by Institute of Management Accountants, Inc. -

Performing Masculinity in Peri-Urban China: Duty, Family, Society

The London School of Economics and Political Science Performing Masculinity in Peri-Urban China: Duty, Family, Society Magdalena Wong A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London December 2016 1 DECLARATION I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/ PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 97,927 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help I confirm that different sections of my thesis were copy edited by Tiffany Wong, Emma Holland and Eona Bell for conventions of language, spelling and grammar. 2 ABSTRACT This thesis examines how a hegemonic ideal that I refer to as the ‘able-responsible man' dominates the discourse and performance of masculinity in the city of Nanchong in Southwest China. This ideal, which is at the core of the modern folk theory of masculinity in Nanchong, centres on notions of men's ability (nengli) and responsibility (zeren). -

Mirror, Moon, and Memory in Eighth-Century China: from Dragon Pond to Lunar Palace

EUGENE Y. WANG Mirror, Moon, and Memory in Eighth-Century China: From Dragon Pond to Lunar Palace Why the Flight-to-the-Moon The Bard’s one-time felicitous phrasing of a shrewd observation has by now fossilized into a commonplace: that one may “hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature; to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.”1 Likewise deeply rooted in Chinese discourse, the same analogy has endured since antiquity.2 As a commonplace, it is true and does not merit renewed attention. When presented with a physical mirror from the past that does register its time, however, we realize that the mirroring or showing promised by such a wisdom is not something we can take for granted. The mirror does not show its time, at least not in a straightforward way. It in fact veils, disfi gures, and ultimately sublimates the historical reality it purports to refl ect. A case in point is the scene on an eighth-century Chinese mirror (fi g. 1). It shows, at the bottom, a dragon strutting or prancing over a pond. A pair of birds, each holding a knot of ribbon in its beak, fl ies toward a small sphere at the top. Inside the circle is a tree fl anked by a hare on the left and a toad on the right. So, what is the design all about? A quick iconographic exposition seems to be in order. To begin, the small sphere refers to the moon. -

Research on the Culturalization of Traditional Industry in Gongjing District Under the Background of Industrial Transformation

Open Access Library Journal 2020, Volume 7, e5940 ISSN Online: 2333-9721 ISSN Print: 2333-9705 Research on the Culturalization of Traditional Industry in Gongjing District under the Background of Industrial Transformation Xiaoxin Jia Sichuan University of Arts and Sciences, Dazhou, China How to cite this paper: Jia, X.X. (2020) Abstract Research on the Culturalization of Traditional Industry in Gongjing District under the The traditional salt culture, agriculture and forestry industry culture, nature Background of Industrial Transformation. and tourism industry culture, and emerging tourism industry culture have Open Access Library Journal, 7: e5940. outstanding advantages in Gongjing District, Zigong City, Sichuan Province. https://doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1105940 Although the trend of cultural industrialization is obvious, the lack of overall Received: November 20, 2019 and long-term development planning, insufficient tourism product develop- Accepted: December 31, 2019 ment, a shortage of professional talents, and inadequate tourists’ participation Published: January 3, 2020 resulted in many problems we have to meet when we try to develop, utilize, integrate and publicize cultural industry resources in Gongjing District. Only Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and Open the government takes the responsibility of making the overall and long-term Access Library Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative planning, exploring the advantages of cultural resources of each district to Commons Attribution International meet the needs of contemporary consumers, recruiting needed talents, and License (CC BY 4.0). leading the transformation of the original industry or business to the emerg- http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ing cultural industry, can we innovate the cultural image of Gongjing District Open Access of Zigong and improve its economic performance. -

Sexuality and Culture in Japan Shifting Dimensions of Desire, Relationship and Society

2021 Spring Semester Sexuality and Culture in Japan Shifting dimensions of desire, relationship and society Instructor/Title Jeffry T. Hester, Ph.D. Office/Building 3329 Office Hours TBA, and by appointment Contacts (E-mail) [email protected] 【Course Outline / Description】 Sexuality is often understood, and experienced, as among the most private and personal aspects of human life. But like other areas of human action, sexuality is shaped within society, and varies cross-culturally and historically. While long-term trends in Japan show young people to be increasingly sexually active, analysts also note a trend of flagging interest in sex among many youth. Young people can choose mates with much less social pressure than in the past, but fewer are finding marriage partners. Sexualization in the media continues apace, even as depictions in the media are subject to scrutiny and regulation. At the same time, voices from increasingly dynamic movements built around lesbian, gay, transgender and queer identities are making their presence felt in the public arena. Sexuality is a contested and dynamic field in Japan. In this course, we will explore this topic with the aim of building a framework for understanding the complex currents of this aspect of human life within the historical, social and cultural context of Japan. Topics for exploration will include changing aspects of mating, romance and marriage; conjugal sexual relations, contraceptive practice, and abortion; sex education in Japanese schools; extramarital relationships and -

Cambridge Papers GENUL: CE MAI URMEAZĂ?

Seria de studii creştine Areopagus 39 Cambridge Papers GENUL: CE MAI URMEAZĂ? Experienţe personale, agende radicale şi dileme năucitoare Christopher Townsend Timişoara 2019 GENUL: CE MAI URMEAZĂ? Experiențe personale, agende radicale și dileme năucitoare Christopher Townsend Articol publicat în seria Cambridge Papers Decembrie 2016 Traducător: Elena Neagoe Centrul de Educație Creștină și Cultură Contemporană Areopagus Timișoara 2019 Originally published in Cambridge Papers series, by The Jubilee Centre (Cambridge, U.K.) under the title Gender: where next? Personal journeys, radical agendas and perplexing dilemmas Volume 25, Number 4, December 2016. © Christopher Townsend 2016 All rights reserved. Published with permission of The Jubilee Centre, St Andrews House, 59 St Andrews Street, Cambridge CB2 3BZ, UK www.jubilee-centre.org Charity Registration Number 288783. Ediția în limba română, publicată cu permisiune, sub titlul GENUL: CE MAI URMEAZĂ? Experiențe personale, agende radicale și dileme năucitoare de Christopher Townsend, apărută sub egida Centrului Areopagus din Timișoara Calea Martirilor nr. 104 www.areopagus.ro în cooperare cu SALLUX Începând cu anul 2011, activitățile desfășurate de Sallux sunt susținute financiar de către Parlamentul European. Responsabilitatea pentru orice comunicare sau publicație redactată de Sallux, sub orice formă sau prin orice mijloc, revine organizației Sallux. Parlamentul European nu este responsabil pentru modurile în care va fi folosită informația conținută aici. Coordonator proiect: Dr. Alexandru Neagoe Toate drepturile rezervate asupra prezentei ediții în limba română. Prima ediție în limba română. Traducător: Elena Neagoe Editor coordonator: Dr. Alexandru Neagoe Cu excepția unor situații când se specifică altfel, pentru citatele biblice s-a folosit traducerea D. Cornilescu. Orice reproducere sau selecție de texte din această carte este permisă doar cu aprobarea în scris a Centrului Areopagus din Timișoara. -

Beyond the Binary: Gender Identity and Mental Health Among Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Adults

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 Beyond the Binary: Gender Identity and Mental Health Among Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Adults Chassitty N. Fiani The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2815 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] BEYOND THE BINARY: GENDER IDENTITY AND MENTAL HEALTH AMONG TRANSGENDER AND GENDER NON-CONFORMING ADULTS by CHASSITTY N. FIANI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Psychology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 CHASSITTY N. FIANI All Rights Reserved ii Beyond the Binary: Gender Identity and Mental Health among Transgender and Gender Non- Conforming Adults by Chassitty N. Fiani This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Psychology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. __________________ __________________________________ Date Kevin L. Nadal Chair of Examining Committee __________________ __________________________________ Date Richard Bodnar Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Dr. Chitra Raghavan Dr. Brett Stoudt Dr. Michelle Fine Dr. David Rivera THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Beyond the Binary: Gender Identity and Mental Health among Transgender and Gender Non- Conforming Adults by Chassitty N. Fiani Advisor: Kevin L. -

The Rise of the Dream-State

The Rise of the Dream-State Trans Agendas, Gender Confusion, Identity & Desire Jasun Horsley 2017 Part One: Psychic Cuckoo-Land “In this fascinating exploration of the cultural models of manhood, When Men Are Women examines the unique world of the nomadic Gabra people, a camel-herding society in northern Kenya. Gabra men denigrate women and feminine things, yet regard their most prestigious men as women. As they grow older, all Gabra men become d’abella, or ritual experts, who have feminine identities. Wood’s study draws from structuralism, psychoanalytic theory, and anthropology to probe the meaning of opposition and ambivalence in Gabra society. When Men Are Women provides a multifaceted view of gender as a cultural construction independent of sex, but nevertheless fundamentally related to it. By turning men into women, the Gabra confront the dilemmas and ambiguities of social life. Wood demonstrates that the Gabra can provide illuminating insight into our own culture’s understanding of gender and its function in society.” –Publisher’s description The transgender question spans the whole spectrum of human interest, from psychological to biological, social to cultural, religious to technological, political to spiritual. It would be hard to conceive of a hotter topic–or button–than the question of when–or if –a man becomes a woman, and vice versa. Wrapped up inside this question is a still deeper one of what makes a human being a human being, what constitutes personal identity, and how much identity is or can be made subject to our desire, and vice versa. Among the countless lesser questions which the subject raises, here are a sample few, some (though probably not all) of which I will address in the following exploration. -

RCI Needs Assessment, Development Strategy, and Implementation Action Plan for Liaoning Province

ADB Project Document TA–1234: Strategy for Liaoning North Yellow Sea Regional Cooperation and Development RCI Needs Assessment, Development Strategy, and Implementation Action Plan for Liaoning Province February L2MN This report was prepared by David Roland-Holst, under the direction of Ying Qian and Philip Chang. Primary contributors to the report were Jean Francois Gautrin, LI Shantong, WANG Weiguang, and YANG Song. We are grateful to Wang Jin and Zhang Bingnan for implementation support. Special thanks to Edith Joan Nacpil and Zhuang Jian, for comments and insights. Dahlia Peterson, Wang Shan, Wang Zhifeng provided indispensable research assistance. Asian Development Bank 4 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City MPP2 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org © L2MP by Asian Development Bank April L2MP ISSN L3M3-4P3U (Print), L3M3-4PXP (e-ISSN) Publication Stock No. WPSXXXXXX-X The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Note: In this publication, the symbol “$” refers to US dollars. Printed on recycled paper 2 CONTENTS Executive Summary ......................................................................................................... 10 I. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 II. Baseline Assessment .................................................................................................. 3 A. -

Seminář Japonských Studií Bakalářská Diplomová Práce

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Seminář japonských studií Bakalářská diplomová práce 2020 Michaela Chupíková Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Seminář japonských studií Japanistika Michaela Chupíková Legislativní změny v Japonsku související s právy homosexuálů po roce 2000 Bakalářská diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Zuzana Rozwałka 2020 Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s využitím uvedených pramenů. Souhlasím s tím, aby práce byla archivována a zpřístupněna ke studijním účelům. ..................................................... Michaela Chupíková Na tomto místě bych ráda poděkovala vedoucí své práce, Mgr. Zuzaně Rozwałce, za její cenné připomínky, trpělivost a čas, který mi věnovala při konzultacích. Obsah Poznámka k formální úpravě práce ......................................................................................................... 6 Úvod ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 1. Úvod do problematiky života japonských homosexuálů ................................................................. 9 2. Legislativa upravující práva japonských homosexuálů před 21. stoletím ..................................... 11 3. Současná legislativa týkající se uznávání stejnopohlavních svazků a partnerského soužití .......... 15 3.1 Ústava Japonska ......................................................................................................................... -

Lanzhou-Chongqing Railway Development Project

Resettlement Planning Document Resettlement Plan Document Stage: Final Project Number: 35354 March 2008 PRC: Lanzhou–Chongqing Railway Development Project Prepared by Ministry of Railways, Gansu Provincial Government, Sichuan Provincial Government, and Chongqing Municipal Government. The resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. RESETTLEMENT PLAN LANZHOU - CHONGQING RAILWAY PROJECT IN THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA MINISTRY OF RAILWAYS, GANSU PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT, SICHUAN PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT, AND CHONGQING MUNICIPAL GOVERNMENT 7 March 2008 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (February 2008) Currency Unit: CNY (Chinese Yuan) US$ 1.00 = CY 7.16 NOTE: In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. ABBREVIATIONS AAOV Average Annual Output Value ACWF All China Women’s Federation ADB Asian Development Bank AP Affected Persons COI Corridor of Impact DMS Detailed Measurement Survey DRC Development & Reform Committee (local government level) EA Executing Agent EIA Environmental Impact Assessment FCTIC Foreign Capital and Technical Import Center FS Feasibility Study FSDI First Survey and Design Institute IA Implementing Agency IOL Inventory of Losses Km Kilometer LARG Land Acquisition and Resettlement Group LCR Lanzhou – Chongqing Railway LYRC LanYu Railway Company MOR Ministry of Railways, PRC mu Unit of land measurement in PRC [15 mu=1 hectare (ha)] NDRC National Development & Reform Committee NGO Non-government Organization PPTA Project Preparatory Technical Assistance PRC People’s Republic of China RCSO Railway Construction Support Office RIB Resettlement Information Booklet RP Resettlement Plan ROW Right-of-Way SEPA State Environmental Protection Agency SSDI Second Survey and Design Institute STI Socially Transmitted Infection TERA TERA International Group, Inc. -

The Transformation of Yunnan in Ming China from the Dali Kingdom to Imperial Province

The Transformation of Yunnan in Ming China From the Dali Kingdom to Imperial Province Edited by Christian Daniels and Jianxiong Ma First published 2020 ISBN: 978-0-367-35336-0 (hbk) ISBN: 978-0-429-33078-0 (ebk) 1 Salt, grain and the change of deities in early Ming western Yunnan Zhao Min (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Funder: Hong Kong University of Science and Technology 1 Salt, grain and the change of deities in early Ming western Yunnan Zhao Min Introduction The Ming conquest of 1382 marked the beginning of the transformation of local society in Yunnan. The Mongol-Yuan relied heavily on the Duan 段, descendants of the royal family of the Dali kingdom (937–1253), to administrate local society in western Yunnan. The first Ming Emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang, continued many Mon- gol-Yuan administrative policies in Yunnan. His practice of appointing local ethnic leaders as native officialstuguan ( 土官) to administer ethnic populations is well known. In addition, he implemented novel measures that became catalysts for change at the level of local society. One such case was the establishment of Guards and Battalions (weisuo 衛所) to control local society and to prevent unrest by indi- genous peoples, particularly those inhabiting the borders with Southeast Asia. The Mongol-Yuan had also stationed troops in Yunnan. However, the Ming innovated by establishing a system for delivering grain to the troops. The early Ming state solved the problem of provisioning the Guards and the Battalions in border areas through two methods. The first was to set up military colonies tuntian( 屯田), while demobilising seven out of every ten soldiers to grow food for the army.