The Transformation of Yunnan in Ming China from the Dali Kingdom to Imperial Province

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5 Sinicization and Indigenization: the Emergence of the Yunnanese

Between Winds and Clouds Bin Yang Chapter 5 Sinicization and Indigenization: The Emergence of the Yunnanese Introduction As the state began sending soldiers and their families, predominantly Han Chinese, to Yunnan, 1 the Ming military presence there became part of a project of colonization. Soldiers were joined by land-hungry farmers, exiled officials, and profit-driven merchants so that, by the end of the Ming period, the Han Chinese had become the largest ethnic population in Yunnan. Dramatically changing local demography, and consequently economic and cultural patterns, this massive and diverse influx laid the foundations for the social makeup of contemporary Yunnan. The interaction of the large numbers of Han immigrants with the indigenous peoples created a 2 new hybrid society, some members of which began to identify themselves as Yunnanese (yunnanren) for the first time. Previously, there had been no such concept of unity, since the indigenous peoples differentiated themselves by ethnicity or clan and tribal affiliations. This chapter will explore the process that led to this new identity and its reciprocal impact on the concept of Chineseness. Using primary sources, I will first introduce the indigenous peoples and their social customs 3 during the Yuan and early Ming period before the massive influx of Chinese immigrants. Second, I will review the migration waves during the Ming Dynasty and examine interactions between Han Chinese and the indigenous population. The giant and far-reaching impact of Han migrations on local society, or the process of sinicization, that has drawn a lot of scholarly attention, will be further examined here; the influence of the indigenous culture on Chinese migrants—a process that has won little attention—will also be scrutinized. -

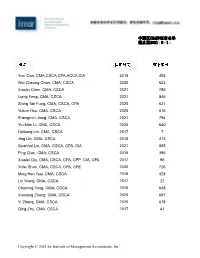

中国区cma持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日

中国区CMA持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日 Yixu Cao, CMA,CSCA,CPA,ACCA,CIA 2019 492 Wai Cheung Chan, CMA, CSCA 2020 622 Xiaolin Chen, CMA, CSCA 2021 785 Liang Feng, CMA, CSCA 2021 845 Shing Tak Fung, CMA, CSCA, CPA 2020 621 Yukun Hsu, CMA, CSCA 2020 676 Shengmin Jiang, CMA, CSCA 2021 794 Yiu Man Li, CMA, CSCA 2020 640 Huikang Lin, CMA, CSCA 2017 7 Jing Lin, CMA, CSCA 2018 415 Quanhui Liu, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CIA 2021 855 Ping Qian, CMA, CSCA 2018 396 Xiaolei Qiu, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CFP, CIA, CFA 2017 96 Yufei Shan, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CFE 2020 726 Ming Han Tsai, CMA, CSCA 2018 428 Lin Wang, CMA, CSCA 2017 22 Chunling Yang, CMA, CSCA 2020 648 Xiaolong Zhang, CMA, CSCA 2020 697 Yi Zhang, CMA, CSCA 2020 678 Qing Zhu, CMA, CSCA 2017 41 Copyright © 2021 by Institute of Management Accountants, Inc. 中国区CMA持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日 Siha A, CMA 2020 81134 Bei Ai, CMA 2020 84918 Danlu Ai, CMA 2021 94445 Fengting Ai, CMA 2019 75078 Huaqin Ai, CMA 2019 67498 Jie Ai, CMA 2021 94013 Jinmei Ai, CMA 2020 79690 Qingqing Ai, CMA 2019 67514 Weiran Ai, CMA 2021 99010 Xia Ai, CMA 2021 97218 Xiaowei Ai, CMA, CIA 2019 75739 Yizhan Ai, CMA 2021 92785 Zi Ai, CMA 2021 93990 Guanfei An, CMA 2021 99952 Haifeng An, CMA 2021 92781 Haixia An, CMA 2016 51078 Haiying An, CMA 2021 98016 Jie An, CMA 2012 38197 Jujie An, CMA 2018 58081 Jun An, CMA 2019 70068 Juntong An, CMA 2021 94474 Kewei An, CMA 2021 93137 Lanying An, CMA, CPA 2021 90699 Copyright © 2021 by Institute of Management Accountants, Inc. -

Testimony Before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission

“China’s Global Quest for Resources and Implications for the United States” January 26, 2012 Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Elizabeth Economy C.V. Starr Senior Fellow and Director, Asia Studies Council on Foreign Relations Introduction China’s quest for resources to fuel its continued rapid economic growth has brought thousands of Chinese enterprises and millions of Chinese workers to every corner of the world. Already China accounts for approximately one-fourth of world demand for zinc, iron and steel, lead, copper, and aluminum. It is also the world’s second largest importer of oil after the United States. And as hundreds of millions of Chinese continue to move from rural to urban areas, the need for energy and other commodities will only continue to increase. No resource, however, is more essential to continued Chinese economic growth than water. It is critical for meeting basic human needs, as well as demands for food and energy. As China’s leaders survey their water landscape, the view is not reassuring. More than 40 mid to large sized cities in northern China, such as Beijing and Tianjin, boast crisis- level water shortages.1 As a result, northern and western cities have been drawing down their groundwater reserves and causing subsidence, which now affects a 60 thousand kilometer area of the North China Plain. 2 According to the director of the Water Research Centre at Peking University Zheng Chunmiao, the water table under the North China Plain is falling at a rate of about a meter per year.3 -

Natürliche Analoga Im Wirtsgestein Salz

Natürliche Analoga im Wirtsgestein Salz Teil 1 Generelle Studie (2011) Teil 2 Detailstudien (2012 – 2013) GRS - 365 Gesellschaft für Anlagen- und Reaktorsicherheit (GRS) gGmbH Natürliche Analoga im Wirtsgestein Salz Teil 1 Generelle Studie (2011) Teil 2 Detailstudien (2012 – 2013) Thomas Brasser Christine Fahrenholz Herbert Kull Artur Meleshyn Heike Mönig Ulrich Noseck Dagmar Schönwiese Jens Wolf Dezember 2014 Anmerkung: Das diesem Bericht zugrunde liegende F&E-Vorhaben wurde im Auftrag des Bundesministe- riums für Wirtschaft und Energie (BMWi) unter dem Kennzeichen FKZ 02E10719 durchgeführt. Die Arbeiten wurden von der Gesellschaft für Anlagen- und Reaktorsicherheit (GRS) gGmbH ausgeführt. Die Verantwortung für den Inhalt dieser Veröffentlichung liegt al- leine bei den Autoren. GRS - 365 ISBN 978-3-944161-46-4 Deskriptoren: Barriere, Endlager, Geochemie, Geologie, Geomechanik, Integrität, mikrobielle Prozesse, Sicherheitsnachweis Vorwort Der vorliegende Bericht stellt die Ergebnisse der Studien zu Natürlichen Analoga im Wirtsgestein Salz zusammen, die im Rahmen des Projektes ISIBEL-II (FKZ: 02E10719) durchgeführt wurden. Diese Arbeiten wurden in zwei Schritten durchge- führt: Im Jahr 2011 erfolgte zunächst eine Zusammenstellung vorhandener Studien und Untersuchungen, die als Natürliche Analoga in einem Sicherheitsnachweis für ein Endlager für wärmeentwickelnde Abfälle Verwendung finden können. Die Bewertung zielte darauf ab, diejenigen Natürlichen Analoga zu identifizieren, die für das in ISIBEL- I (FKZ: 02E10055) entwickelte Sicherheits- und Nachweiskonzept eine Rolle spielen. Erfüllen Natürliche Analoga diese Voraussetzung nicht, ist ihre Verwendung im Sicher- heitsnachweis ohne Bedeutung und kann von den eigentlich zu machenden Aussagen ablenken. Bei dieser Vorgehensweise wurden auch einzelne, bisher hinsichtlich Natür- licher Analoga nicht betrachtete Aspekte identifiziert, für die deren Einsatz jedoch sinn- voll wäre; dies betrifft z. -

Performing Masculinity in Peri-Urban China: Duty, Family, Society

The London School of Economics and Political Science Performing Masculinity in Peri-Urban China: Duty, Family, Society Magdalena Wong A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London December 2016 1 DECLARATION I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/ PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 97,927 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help I confirm that different sections of my thesis were copy edited by Tiffany Wong, Emma Holland and Eona Bell for conventions of language, spelling and grammar. 2 ABSTRACT This thesis examines how a hegemonic ideal that I refer to as the ‘able-responsible man' dominates the discourse and performance of masculinity in the city of Nanchong in Southwest China. This ideal, which is at the core of the modern folk theory of masculinity in Nanchong, centres on notions of men's ability (nengli) and responsibility (zeren). -

GEOTHERMAL RESOURCES in CHINA

GEOTHERMAL RESOURCES in CHINA January 1996 Prepared by: Anthony Taylor Zheng Li Bob Lawrence & Associates, Inc. 424 N. Washington Street Alexandria, VA 22314 INTRODUCTION In recent years China has experienced rapid economic expansion as it endeavors to bring about a modern standard of living for its huge population. The GNP grew at an average rate of 9.5% during the decade of the 80's; and 13%, in 1992 and ‘93. Certain Special Economic Zones in southern China have raced at over 20% per year recently. These trends are expected to continue, at least for the next few years. Growth in the economy has brought a demand for new infrastructure. Additional electrical generating capacity is needed, both to meet the needs of new industries and the growing middle class of consumers as well as to close a persistent gap between supply and demand. The Ministry of Electrical Power in Beijing announced an ambitious goal of installing 100 to 130 GW of new generating capacity by the year 2000. To achieve this goal, the Chinese will have to increase capacity at a rate that is more than four times the present level of expansion in the US. Most of the new capacity will be provided using coal-fired steam turbine systems in the 300 to 600 MW range, thereby further increasing an already-heavy reliance on coal for energy production. Furthermore, the Ministry of Electrical Power projects that the percentage of annual coal production (currently 1.1 billion tons) devoted to electrical generation will rise from 29% to 60% by 2010. -

Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 5-16-2016 12:00 AM Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain Robert Jackson Woodcock The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Professor Alexander Meyer The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Classics A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Robert Jackson Woodcock 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Indo- European Linguistics and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Woodcock, Robert Jackson, "Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3775. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3775 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Language is one of the most significant aspects of cultural identity. This thesis examines the evidence of languages in contact in Roman Britain in order to determine the role that language played in defining the identities of the inhabitants of this Roman province. All forms of documentary evidence from monumental stone epigraphy to ownership marks scratched onto pottery are analyzed for indications of bilingualism and language contact in Roman Britain. The language and subject matter of the Vindolanda writing tablets from a Roman army fort on the northern frontier are analyzed for indications of bilingual interactions between Roman soldiers and their native surroundings, as well as Celtic interference on the Latin that was written and spoken by the Roman army. -

Mirror, Moon, and Memory in Eighth-Century China: from Dragon Pond to Lunar Palace

EUGENE Y. WANG Mirror, Moon, and Memory in Eighth-Century China: From Dragon Pond to Lunar Palace Why the Flight-to-the-Moon The Bard’s one-time felicitous phrasing of a shrewd observation has by now fossilized into a commonplace: that one may “hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature; to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.”1 Likewise deeply rooted in Chinese discourse, the same analogy has endured since antiquity.2 As a commonplace, it is true and does not merit renewed attention. When presented with a physical mirror from the past that does register its time, however, we realize that the mirroring or showing promised by such a wisdom is not something we can take for granted. The mirror does not show its time, at least not in a straightforward way. It in fact veils, disfi gures, and ultimately sublimates the historical reality it purports to refl ect. A case in point is the scene on an eighth-century Chinese mirror (fi g. 1). It shows, at the bottom, a dragon strutting or prancing over a pond. A pair of birds, each holding a knot of ribbon in its beak, fl ies toward a small sphere at the top. Inside the circle is a tree fl anked by a hare on the left and a toad on the right. So, what is the design all about? A quick iconographic exposition seems to be in order. To begin, the small sphere refers to the moon. -

ABSTRACT LU, CHI. Natural and Human Impacts on Recent

ABSTRACT LU, CHI. Natural and Human Impacts on Recent Development of Yangtze River and Mekong River Deltas. (Under the direction of Dr. Paul Liu). The Yangtze River Delta is the largest delta in China and is also a highly populated delta where metropolitan cities such as Shanghai are located. The evolution of Yangtze River Delta will directly influence the economics and environment in this area. The sediment flux from Yangtze into the delta decreased during the past three decades and the operation of world’s largest hydropower project, Three Gorges Dam, made this situation much more severe. In the delta area, another large project called Deep Water Navigation Channel was also completed in recent years. Mekong River Delta is another major delta in Asia and also has a lot of dams in the river basin. To document the relationship between human impacts on the large river basin and coastal evolution, in this study, we used Jiuduan Island of Yangtze River Delta and two islands of Mekong River Delta as examples and utilized Landsat data to show how these island’s shoreline changed with the trend of decreased sediment discharge. In Mekong River Delta, the shoreline change agreed well with the sediment flux, eroding from 1989 to 1996 and prograding from 1996 to 2002. In Yangtze River Delta, shoreline kept growing before Three Gorges Dams was operating, eroded from 2003 to 2009 and then prograded again from 2011 to 2013. The main reason for the shoreline progradation from 2011 to 2013 was the impact of the Deep Water Navigation Channel project which totally changed the sediment transport process around Jiuduan Island. -

ASJ Introduction to "Historical and Cultural Significance of Admiral Zheng He's Ocean Voyages"

ASJ Introduction to "Historical and Cultural Significance of Admiral Zheng He's Ocean Voyages" Those in power control the future by controlling the past, wrote George Orwell. Nowhere is this truth more dead on target than in European historiography, with its hubris-that enduring sense of being better than the rest. This claim of European superiority, according to Alam (2002), has been put forward with regard to rationality, freedom, individuality, inventiveness, daring, curiosity and tolerance; in turn, these qualities have been translated into superior achievements in technology, wars, management, capitalism, industrialization, and shipping, among others. A case in point is the European effort to explain, or explain away, Zheng He's expeditions in the l4'h century as a case of irrational decision making, of an inability to resist the gratification of whims and desires of the voyager's Chinese masters. By contrast, European expeditions were presented as technological triumphs in an era of rationalism and economic adventure. Such Eurocentrism takes a variety of forms. In the 1990 BBC television documentary series Road to Xanadu, for instance, Zheng He's maritime exploration, according to Cao (2006), is assailed as "an expendable luxury"-an impractical exercise in the consumption (rather than production) of material wealth. To emphasize the difference, the documentary suggests that when Europe embarked on its profit-seeking overseas colonial undertaking, the aim was "to grasp the riches of trade 25 26 with Asia." Or again, it is common for European historiographers to devalue China's maritime reach Gong after Zheng He's expeditions), by asking rhetorically (as did Landes, 1998) why European sailing vessels could call at Shanghai or Canton, while no Chinese junks ever anchored in London (Goldstone, 2001 ). -

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome William E. Dunstan ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK ................. 17856$ $$FM 09-09-10 09:17:21 PS PAGE iii Published by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.rowmanlittlefield.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright ᭧ 2011 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. All maps by Bill Nelson. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. The cover image shows a marble bust of the nymph Clytie; for more information, see figure 22.17 on p. 370. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dunstan, William E. Ancient Rome / William E. Dunstan. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7425-6832-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7425-6833-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7425-6834-1 (electronic) 1. Rome—Civilization. 2. Rome—History—Empire, 30 B.C.–476 A.D. 3. Rome—Politics and government—30 B.C.–476 A.D. I. Title. DG77.D86 2010 937Ј.06—dc22 2010016225 ⅜ϱ ீThe paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/ NISO Z39.48–1992. Printed in the United States of America ................ -

Ming China As a Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, and Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 Weicong Duan Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Winter 12-15-2018 Ming China As A Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, And Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 Weicong Duan Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Duan, Weicong, "Ming China As A Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, And Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620" (2018). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1719. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/1719 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Dissertation Examination Committee: Steven B. Miles, Chair Christine Johnson Peter Kastor Zhao Ma Hayrettin Yücesoy Ming China as a Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, and Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 by Weicong Duan A dissertation presented to The Graduate School of of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2018 St. Louis, Missouri © 2018,