Appendices, Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natürliche Analoga Im Wirtsgestein Salz

Natürliche Analoga im Wirtsgestein Salz Teil 1 Generelle Studie (2011) Teil 2 Detailstudien (2012 – 2013) GRS - 365 Gesellschaft für Anlagen- und Reaktorsicherheit (GRS) gGmbH Natürliche Analoga im Wirtsgestein Salz Teil 1 Generelle Studie (2011) Teil 2 Detailstudien (2012 – 2013) Thomas Brasser Christine Fahrenholz Herbert Kull Artur Meleshyn Heike Mönig Ulrich Noseck Dagmar Schönwiese Jens Wolf Dezember 2014 Anmerkung: Das diesem Bericht zugrunde liegende F&E-Vorhaben wurde im Auftrag des Bundesministe- riums für Wirtschaft und Energie (BMWi) unter dem Kennzeichen FKZ 02E10719 durchgeführt. Die Arbeiten wurden von der Gesellschaft für Anlagen- und Reaktorsicherheit (GRS) gGmbH ausgeführt. Die Verantwortung für den Inhalt dieser Veröffentlichung liegt al- leine bei den Autoren. GRS - 365 ISBN 978-3-944161-46-4 Deskriptoren: Barriere, Endlager, Geochemie, Geologie, Geomechanik, Integrität, mikrobielle Prozesse, Sicherheitsnachweis Vorwort Der vorliegende Bericht stellt die Ergebnisse der Studien zu Natürlichen Analoga im Wirtsgestein Salz zusammen, die im Rahmen des Projektes ISIBEL-II (FKZ: 02E10719) durchgeführt wurden. Diese Arbeiten wurden in zwei Schritten durchge- führt: Im Jahr 2011 erfolgte zunächst eine Zusammenstellung vorhandener Studien und Untersuchungen, die als Natürliche Analoga in einem Sicherheitsnachweis für ein Endlager für wärmeentwickelnde Abfälle Verwendung finden können. Die Bewertung zielte darauf ab, diejenigen Natürlichen Analoga zu identifizieren, die für das in ISIBEL- I (FKZ: 02E10055) entwickelte Sicherheits- und Nachweiskonzept eine Rolle spielen. Erfüllen Natürliche Analoga diese Voraussetzung nicht, ist ihre Verwendung im Sicher- heitsnachweis ohne Bedeutung und kann von den eigentlich zu machenden Aussagen ablenken. Bei dieser Vorgehensweise wurden auch einzelne, bisher hinsichtlich Natür- licher Analoga nicht betrachtete Aspekte identifiziert, für die deren Einsatz jedoch sinn- voll wäre; dies betrifft z. -

Transmission of Han Pictorial Motifs Into the Western Periphery: Fuxi and Nüwa in the Wei-Jin Mural Tombs in the Hexi Corridor*8

DOI: 10.4312/as.2019.7.2.47-86 47 Transmission of Han Pictorial Motifs into the Western Periphery: Fuxi and Nüwa in the Wei-Jin Mural Tombs in the Hexi Corridor*8 ∗∗ Nataša VAMPELJ SUHADOLNIK 9 Abstract This paper examines the ways in which Fuxi and Nüwa were depicted inside the mu- ral tombs of the Wei-Jin dynasties along the Hexi Corridor as compared to their Han counterparts from the Central Plains. Pursuing typological, stylistic, and iconographic approaches, it investigates how the western periphery inherited the knowledge of the divine pair and further discusses the transition of the iconographic and stylistic design of both deities from the Han (206 BCE–220 CE) to the Wei and Western Jin dynasties (220–316). Furthermore, examining the origins of the migrants on the basis of historical records, it also attempts to discuss the possible regional connections and migration from different parts of the Chinese central territory to the western periphery. On the basis of these approaches, it reveals that the depiction of Fuxi and Nüwa in Gansu area was modelled on the Shandong regional pattern and further evolved into a unique pattern formed by an iconographic conglomeration of all attributes and other physical characteristics. Accordingly, the Shandong region style not only spread to surrounding areas in the central Chinese territory but even to the more remote border regions, where it became the model for funerary art motifs. Key Words: Fuxi, Nüwa, the sun, the moon, a try square, a pair of compasses, Han Dynasty, Wei-Jin period, Shandong, migration Prenos slikovnih motivov na zahodno periferijo: Fuxi in Nüwa v grobnicah s poslikavo iz obdobja Wei Jin na območju prehoda Hexi Izvleček Pričujoči prispevek v primerjalni perspektivi obravnava upodobitev Fuxija in Nüwe v grobnicah s poslikavo iz časa dinastij Wei in Zahodni Jin (220–316) iz province Gansu * The author acknowledges the financial support of the Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS) in the framework of the research core funding Asian languages and Cultures (P6-0243). -

EAF3506 | University of Exeter

09/24/21 EAF3506 | University of Exeter EAF3506 View Online Taiwan New Cinema and Beyond: Authorship, Transnationality, Historiography 1. Yeh, Emilie Yueh-yu, Davis, Darrell William: Taiwan film directors: a treasure island. Columbia University Press, Chichester (2005). 2. Berry, Chris, Lu, Feii: Island on the edge: Taiwan new cinema and after. Hong Kong University Press, Hong Kong (2005). 3. Berry, Michael: Speaking in images: interviews with contemporary Chinese filmmakers. Columbia University Press, Chichester (2005). 4. Davis, Darrell William, Chen, Ruxiu: Cinema Taiwan: politics, popularity and state of the arts. Routledge, London (2007). 5. Hong, Gou-Juin: Taiwan cinema: a contested nation on screen. Palgrave Macmillan, New York (2011). 6. Lu, Tonglin: Confronting modernity in the cinemas of Taiwan and Mainland China. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2002). 1/21 09/24/21 EAF3506 | University of Exeter 7. Yip, June Chun: Envisioning Taiwan: fiction, cinema, and the nation in the cultural imaginary. Duke University Press, Durham (2004). 8. • MCLC (Modern Chinese Literature and Culture) Resource Centre . 9. •Taiwan Government Information Office‘s (GIO) ’Taiwan Cinema” . 10. Eng, R.: Taiwan: An Annotated Directory of Internet Resources. 11. Taiwan Ministry of Culture. 12. Ching, Leo T. S.: Becoming ‘Japanese’: colonial Taiwan and the politics of identity formation. University of California Press, Berkeley, Calif (2001). 13. Liao, Binghui, Wang, Dewei: Taiwan under Japanese colonial rule, 1895-1945: history, culture, memory. Columbia University Press, New York (2006). 14. Roy, Denny: Taiwan: a political history. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, N.Y. (2003). 2/21 09/24/21 EAF3506 | University of Exeter 15. Rubinstein, Murray A.: Taiwan: a new history. -

TAIWAN BIENNIAL FILM FESTIVAL 2019 FILM INFORMATION/TIMELINE October 18, 2019 7:30 Pm

TAIWAN BIENNIAL FILM FESTIVAL 2019 FILM INFORMATION/TIMELINE October 18, 2019 7:30 pm – Opening Film HEAVY CRAVING Billy Wilder Theater In a special celebration, UCLA Film & Television Archive and Taiwan Academy in Los Angeles are excited to accompany the North American premiere of the film with a guest appearance by the film’s acclaimed Director/Screenwriter Hsieh Pei-ju, who will participate in a post-screening Q&A. HEAVY CRAVING (2019) Synopsis: a talented chef for a preschool run by her demanding mother, Ying-juan earns praise for her culinary creations but scorn for her weight. Even the children she feeds have dubbed her “Ms. Dinosaur” for her size. Joining a popular weight loss program seems like an answer but it’s the unlikely allies she finds outside the program—and the obstacles she faces in it—that help her find a truer path to happiness. Writer-director Hsieh Pei-ju doesn’t shy away from the darker sides of self-discovery in what ultimately proves a rousing feature debut, winner of the Audience’s Choice award at this year’s Taipei Film Festival. Director/Screenwriter: Hsieh Pei-ju. Cast: Tsai Jia-yin, Yao Chang, Samantha Ko. October 19, 2019 3:00 pm – “Focus on Taiwan” Panel Billy Wilder Theater Admission: Free With the ‘Focus on Taiwan’ panel UCLA Film & Television Archive and Taiwan Academy in Los Angeles are thrilled to present a curated afternoon of timely conversations about issues facing the Taiwan film industry at home and abroad, including gender equality and inclusion of women and the LGBTQ community on screen and behind the camera, the challenges of marketing Taiwanese productions internationally and more. -

Download Heroic Grace: the Chinese Martial Arts Film Catalog (PDF)

UCLA Film and Television Archive Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in San Francisco HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Front and inside cover: Lau Kar-fai (Gordon Liu Jiahui) in THE 36TH CHAMBER OF SHAOLIN (SHAOLIN SANSHILIU FANG ) present HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film catalog (2003) is a publication of the UCLA Film and Television Archive, Los Angeles, USA. Editors: David Chute (Essay Section) Cheng-Sim Lim (Film Notes & Other Sections) Designer: Anne Coates Printed in Los Angeles by Foundation Press ii CONTENTS From the Presenter Tim Kittleson iv From the Presenting Sponsor Annie Tang v From the Chairman John Woo vi Acknowledgments vii Leaping into the Jiang Hu Cheng-Sim Lim 1 A Note on the Romanization of Chinese 3 ESSAYS Introduction David Chute 5 How to Watch a Martial Arts Movie David Bordwell 9 From Page to Screen: A Brief History of Wuxia Fiction Sam Ho 13 The Book, the Goddess and the Hero: Sexual Bérénice Reynaud 18 Aesthetics in the Chinese Martial Arts Film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon—Passing Fad Stephen Teo 23 or Global Phenomenon? Selected Bibliography 27 FILM NOTES 31-49 PROGRAM INFORMATION Screening Schedule 51 Print & Tape Sources 52 UCLA Staff 53 iii FROM THE PRESENTER Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film ranks among the most ambitious programs mounted by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, taking five years to organize by our dedicated and intrepid Public Programming staff. -

340336 1 En Bookbackmatter 251..302

A List of Historical Texts 《安禄山事迹》 《楚辭 Á 招魂》 《楚辭注》 《打馬》 《打馬格》 《打馬錄》 《打馬圖經》 《打馬圖示》 《打馬圖序》 《大錢圖錄》 《道教援神契》 《冬月洛城北謁玄元皇帝廟》 《風俗通義 Á 正失》 《佛说七千佛神符經》 《宮詞》 《古博經》 《古今圖書集成》 《古泉匯》 《古事記》 《韓非子 Á 外儲說左上》 《韓非子》 《漢書 Á 武帝記》 《漢書 Á 遊俠傳》 《和漢古今泉貨鑒》 《後漢書 Á 許升婁傳》 《黃帝金匱》 《黃神越章》 《江南曲》 《金鑾密记》 《經國集》 《舊唐書 Á 玄宗本紀》 《舊唐書 Á 職官志 Á 三平准令條》 《開元別記》 © Springer Science+Business Media Singapore 2016 251 A.C. Fang and F. Thierry (eds.), The Language and Iconography of Chinese Charms, DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-1793-3 252 A List of Historical Texts 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷二 Á 戲擲金錢》 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷三》 《雷霆咒》 《類編長安志》 《歷代錢譜》 《歷代泉譜》 《歷代神仙通鑑》 《聊斋志異》 《遼史 Á 兵衛志》 《六甲祕祝》 《六甲通靈符》 《六甲陰陽符》 《論語 Á 陽貨》 《曲江對雨》 《全唐詩 Á 卷八七五 Á 司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《泉志 Á 卷十五 Á 厭勝品》 《勸學詩》 《群書類叢》 《日本書紀》 《三教論衡》 《尚書》 《尚書考靈曜》 《神清咒》 《詩經》 《十二真君傳》 《史記 Á 宋微子世家 Á 第八》 《史記 Á 吳王濞列傳》 《事物绀珠》 《漱玉集》 《說苑 Á 正諫篇》 《司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《私教類聚》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十一 Á 志第一百四 Á 輿服三 Á 天子之服 皇太子附 后妃之 服 命婦附》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十二 Á 志第一百五 Á 輿服四 Á 諸臣服上》 《搜神記》 《太平洞極經》 《太平廣記》 《太平御覽》 《太上感應篇》 《太上咒》 《唐會要 Á 卷八十三 Á 嫁娶 Á 建中元年十一月十六日條》 《唐兩京城坊考 Á 卷三》 《唐六典 Á 卷二十 Á 左藏令務》 《天曹地府祭》 A List of Historical Texts 253 《天罡咒》 《通志》 《圖畫見聞志》 《退宮人》 《萬葉集》 《倭名类聚抄》 《五代會要 Á 卷二十九》 《五行大義》 《西京雜記 Á 卷下 Á 陸博術》 《仙人篇》 《新唐書 Á 食貨志》 《新撰陰陽書》 《續錢譜》 《續日本記》 《續資治通鑑》 《延喜式》 《顏氏家訓 Á 雜藝》 《鹽鐵論 Á 授時》 《易經 Á 泰》 《弈旨》 《玉芝堂談薈》 《元史 Á 卷七十八 Á 志第二十八 Á 輿服一 儀衛附》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 符圖部》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 三洞經教部》 《韻府帬玉》 《戰國策 Á 齊策》 《直齋書錄解題》 《周易》 《莊子 Á 天地》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二百一十六 Á 唐紀三十二 Á 玄宗八載》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二一六 Á 唐天寶十載》 A Chronology of Chinese Dynasties and Periods ca. -

Chinese Redemptive Societies and Salvationist Religion: Historical

Redemptive Societies: Historical Phenomenon or Sociological Category? Chinese Redemptive Societies and Salvationist Religion: Historical Phenomenon or Sociological Category? David A. Palmer Assistant Professor University of Hong Kong Dept. of Sociology and Centre for Anthropological Research1 PRE-PUBLICATION VERSION Published in Journal of Chinese Theatre, Ritual and Folklore/ Minsu Quyi 172 (2011), pp. 21-72. Abstract This paper outlines a conceptual framework for research on Chinese redemptive societies and salvationist religion. I begin with a review of past scholarship on Republican-era salvationist movements and their contemporary communities, comparing their treatment in three bodies of scholarly literature dealing with the history and scriptures of “sectarianism” in the late imperial era, the history of “secret societies” of the republican period, and the ethnography of “popular religion” in the contemporary Chinese world. I then assess Prasenjit Duara’s formulation of “redemptive societies” as a label for a constellation of religious groups active in the republican period, and, after comparing the characteristics of the main groups in question (such as the Tongshanshe, Daoyuan, Yiguandao and others), argue that an anaytical distinction needs to be made between “salvationist movements” as a sociological category, which have appeared throughout Chinese history and until today, and redemptive societies as one historical instance of a wave of salvationist movements, which appeared in the republican period and bear the imprint of the socio-cultural conditions and concerns of that period. Finally, I discuss issues for future research and the significance of redemptive societies in the social, political and intellectual history of modern China, and in the modern history of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. -

The Ming Dynasty

The East Asian World 1400–1800 Key Events As you read this chapter, look for the key events in the history of the East Asian world. • China closed its doors to the Europeans during the period of exploration between 1500 and 1800. • The Ming and Qing dynasties produced blue-and-white porcelain and new literary forms. • Emperor Yong Le began renovations on the Imperial City, which was expanded by succeeding emperors. The Impact Today The events that occurred during this time still impact our lives today. • China today exports more goods than it imports. • Chinese porcelain is collected and admired throughout the world. • The Forbidden City in China is an architectural wonder that continues to attract people from around the world. • Relations with China today still require diplomacy and skill. World History Video The Chapter 16 video, “The Samurai,” chronicles the role of the warrior class in Japanese history. 1514 Portuguese arrive in China Chinese sailing ship 1400 1435 1470 1505 1540 1575 1405 1550 Zheng He Ming dynasty begins voyages flourishes of exploration Ming dynasty porcelain bowl 482 Art or Photo here The Forbidden City in the heart of Beijing contains hundreds of buildings. 1796 1598 1644 1750 White Lotus HISTORY Japanese Last Ming Edo is one of rebellion unification emperor the world’s weakens Qing begins dies largest cities dynasty Chapter Overview Visit the Glencoe World History Web site at 1610 1645 1680 1715 1750 1785 tx.wh.glencoe.com and click on Chapter 16–Chapter Overview to preview chapter information. 1603 1661 1793 Tokugawa Emperor Britain’s King rule begins Kangxi begins George III sends “Great 61-year reign trade mission Peace” to China Japanese samurai 483 Emperor Qianlong The meeting of Emperor Qianlong and Lord George Macartney Mission to China n 1793, a British official named Lord George Macartney led a mission on behalf of King George III to China. -

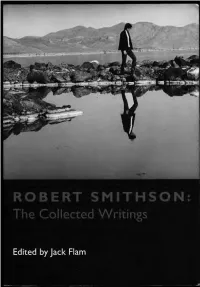

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) . -

The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933

The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Schluessel, Eric T. 2016. The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493602 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933 A dissertation presented by Eric Tanner Schluessel to The Committee on History and East Asian Languages in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History and East Asian Languages Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April, 2016 © 2016 – Eric Schluessel All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Mark C. Elliott Eric Tanner Schluessel The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933 Abstract This dissertation concerns the ways in which a Chinese civilizing project intervened powerfully in cultural and social change in the Muslim-majority region of Xinjiang from the 1870s through the 1930s. I demonstrate that the efforts of officials following an ideology of domination and transformation rooted in the Chinese Classics changed the ways that people associated with each other and defined themselves and how Muslims understood their place in history and in global space. -

The Maine Broadcaster Local History Collections

Portland Public Library Portland Public Library Digital Commons The Maine Broadcaster Local History Collections 10-1947 The Maine Broadcaster : October 1947 (Vol. 3, No. 10) Maine Broadcasting System (WCSH Portland, ME) Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.portlandlibrary.com/mainebroadcaster TBE BROADCASTING~!·~~ MAINE BROADCASTER: SYSTEM\. AJllliat e PUBLISHED AS AN AID TO BETTER RADIO LISTENING Vol. III , N o. 10 P ortln.ncl, Maine, October, 1947 Price, F ive Cents HOUR-LONG PLAYS ON NBC's FORD THEATRE MeBs To Offer No Crime Or Mystery Programs Howard Lindsay Frill Foothall ;; Before 9.30 P.M. On NBC Coverage Emcee-Narrator The · :iona l~ .Broadcasting Com be broadcast over the NBC network The Maine Broadcasting System and pany convention, meeting in Atlantic before 9:30 p. m .. ." Of New Series ~BC will offer a full schedule of the City, N. )., this past month, unani It is important co reiterate now, The hou.r-long Ford Theater starts nution's top football games this fall mously"'<ndoprcd a propos:il that, ef for the information of the general Sundny, Oct. 5, 011 WSCH, vVRDO with Saturday afternoon play-by-play fective ·1an. 1, 1948, "no series of public, some of the policies of NBC: and \.VLBZ with the noted playwdght broadcasts. The fi.rst important game detective, crime or mystery cype 1. No program will be broadcast prnducer-actor, H oward Lindsay, w; of the season-the Minnesota-Wash programs" will be broadcast over which glorifies or justifies crime, master of ceremonies and narrator. It ington conrest-al.ready has been aired NBC before 9: 30 p. -

Nayancheng's Botched Mission in the White Lotus

Broken Passage to the Summit: Nayancheng’s Botched Mission in the White Lotus War Yingcong Dai In ruling an extensive empire in pre-modern times, a monarch often dele- gated his authority to his representatives. In China, this practice reached its apogee during the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) when the Manchu rulers devel- oped a sophisticated system of appointing both provincial governors and governors-general for its regular provinces and designated administrative commissioners for its protectorates. In addition to territorial administrators, the political centre of an empire also detailed special commissioners, from time to time, to inspect its territories and to accomplish special tasks, civil or military, which served as another means to cement the bonds between the centre and the provinces. During the Qing dynasty, special commissioners sent by the imperial court were often granted the ad hoc title, ‘Qinchai Dachen’ or ‘Special Imperial Commissioner.’ For some commissioners who were political upstarts, a successful mission could serve as a steppingstone to more promi- nent positions because the achievement, as well as the experience, enhanced their credentials. But a failed mission could well lead to disgrace, punishment, or worse. This chapter sheds light on the story of an imperial commissioner in Qing China. In 1799, a Manchu aristocrat, Nayancheng (1764–1833), was appointed as a Special Imperial Commissioner to supervise the suppression campaign against a sectarian rebellion, the White Lotus Rebellion (1796–1805). Not only was he expected to inject new energy into the enervated campaign and pro- mote the reform at the warfront, but it was also anticipated that he would prove his own worthiness so that he could be named to lead the Grand Council, the Qing monarch’s key advisory body.