Beyond the Binary: Gender Identity and Mental Health Among Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Adults

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promoting a Queer Agenda for Hate Crime Scholarship

LGBT hate crime : promoting a queer agenda for hate crime scholarship PICKLES, James Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/24331/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version PICKLES, James (2019). LGBT hate crime : promoting a queer agenda for hate crime scholarship. Journal of Hate Studies, 15 (1), 39-61. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk LGBT Hate Crime: Promoting a Queer Agenda for Hate Crime Scholarship James Pickles Sheffield Hallam University INTRODUCTION Hate crime laws in England and Wales have emerged as a response from many decades of the criminal justice system overlooking the structural and institutional oppression faced by minorities. The murder of Stephen Lawrence highlighted the historic neglect and myopia of racist hate crime by criminal justice agencies. It also exposed the institutionalised racism within the police in addition to the historic neglect of minority groups (Macpherson, 1999). The publication of the inquiry into the death of Ste- phen Lawrence prompted a move to protect minority populations, which included the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community. Currently, Section 28 of the Crime and Disorder Act (1998) and Section 146 of the Criminal Justice Act (2003) provide courts the means to increase the sentences of perpetrators who have committed a crime aggravated by hostility towards race, religion, sexuality, disability, and transgender iden- tity. Hate crime is therefore not a new type of crime but a recognition of identity-aggravated crime and an enhancement of existing sentences. -

Black Boi, Boss Bitch

Black Boi, Boss Bitch Lauryn Hill 18 Jan 1995 - 26 Sep 1998 BLACK QUEER LOOKS Y todo comenzo bailando.... 27 Oct 1998 “Y todo comenzo bailando”...The earliest memories I can recall of my existence are festive. 20 Pound Pots of pernil & pigfeet. Pasteles, Gandulez, Guinea, Pollo Guisado. Habichuelas. 5 different types of beans & 5 different dishes on one plate. Even if only 4 niggas pulled up to the crib, abuela was always cooking for 40. The image of her red lipstick stain on hefty glasses of Budweiser that once contained Goya olives is forever etched in my mind. This was that poor boricua family that stored rice & beans in “I Can’t Believe it’s Not Butter” containers.The kind of family that blasted Jerry Rivera’s & Frankie Ruiz voices over dollar-store speakers. The kind that prized Marc Anthony, Hector LaVoe, El Gran Combo, La India, Tito Rojas. Victor Manuelle. Salsa Legends that put abuela's feet to work. My cousin Nina & her wife Iris who sparked their Ls in the bathroom, waving around floor length box braids, and bomb ass butch-queen aesthetics. “Pero nino, you hoppin on the cyph?. Uncle Negro or “Black”as we called him for his rich dark-skin, stay trying to wife my mom’s friends. 7:11 pm. 7 pounds 8 oz. October 27th. Maybe it was the lucky 7. Maybe it was fated for them to welcome another, intensely-loving Scorpio into their home. Or maybe it was just another blissful evening in the barrio. Where Bottles of Henny would be popped, and cousins & aunts & uncles you didn’t even know you had would reappear. -

Attitudes Toward Bisexuality According to Sexual Orientation and Gender

Fairfield University DigitalCommons@Fairfield Graduate School of Education & Allied GSEAP Faculty Publications Professions 7-2016 Attitudes Toward Bisexuality According to Sexual Orientation and Gender Katherine M. Hertlein Erica E. Hartwell Fairfield University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/education-facultypubs Copyright 2016 Taylor and Francis. A post-print has been archived with permission from the copyright holder. This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Journal of Bisexuality in 2016, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/ 15299716.2016.1200510 Peer Reviewed Repository Citation Hertlein, Katherine M. and Hartwell, Erica E., "Attitudes Toward Bisexuality According to Sexual Orientation and Gender" (2016). GSEAP Faculty Publications. 126. https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/education-facultypubs/126 Published Citation Hertlein, Katherine M., Erica E. Hartwell, and Mashara E. Munns. "Attitudes Toward Bisexuality According to Sexual Orientation and Gender." Journal of Bisexuality (July 2016) 16(3): 1-22. This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

The Oxford Democrat : Vol. 70. No.52

The Oxford Democrat. 1903. NUMBER 52. VOLUME 70. SOUTH PARIS, MAINE, TUESDAY, DECEMBER 29, KH tiMh'.l lo; ili l 'y. oners, but Beverley soon suspected tl tt rutiler item, who was coining out 01 never fails. But he'll tell Clark to eta.v JUNKS, Fruit Marketing and Storage. *«W>4^3*4HfcHêHîMlHWHfr^ Furii «worth was on his guard in a C. THE a "tralllc In hah," ae the terrible bu-tl- u cabin nut far away, beard and knew where he is, and Vigo can do no more." ^ AMONG FARMERS. Some of the most and twin!;iing. lie set his jaw and uttered preening impor- ness had been named, was going on. the voice. What effect Helm's hold and appar- & Machinist, in- a< I!· htnh.· Smith tant relating to the fri\it f nil ugly oath: then qiii-k MA1NK. questions miH"î Savages came In from far away with Ho. lio. little cried artless talk h:id upon Hamilton's SOUTH PARIS, are those that out of the y4"i«P my lady!" ently at the with "SFLKD THIS PLOW." dustry grow he struck siucwlse pistol of general machinery, steam en in horticulture to scalps yet scarcely dry dangling at Adrien ne's captor in a breezy, jocund mind Is not recorded, hut the meager Manufacturer anil tools., .present tendency pro- his blade. It was a move which might mill work, spool machinery their belis. It made the Vir- "You wouldn't run over u facts at command show that ,'lties, drille made and duce each fruit in that section where it #| young tone. -

Sexual Orientation and Trans Sexuality 101

Sexual Orientation and Trans Sexuality 101 Michael L Krychman MD Executive Director of the Southern California Center for Sexual Health and Survivorship Medicine Associate Clinical Professor UCI AASECT Certified Sexual Counselor Developmental Sexuality Review • Things do go wrong! – Chromosomal – Hormonal Gender Identity & Sexual Orientation are Different! • Every individual has a – biological sex – a gender identity – a sexual orientation. – (All can be considered fluid!) • Being transgender does not mean you’re gay and being gay does not mean you’re transgender. – There is overlap, in part because gender variance is often seen in gay context. – Masculine females and feminine males are often assumed to be gay; – “Anti-gay” discrimination and violence often targets gender expression, not sexuality Anatomy does not determine sexual orientation Homophobia is different than Transphobia Case: Ego Dystonic Bisexual Transgender Male becoming a female Has both a male and female partner Parts: heterosexual Identity: homosexual Gender Identity & Sexual Orientation are Different! • Coming out as gay is different than coming out as transexual • Trans people are often marginalized in G/L context. • How do we apply cultural competency lessons that apply around heterosexism to gender variance? • CDC categorizes MTFs and partners as MSM; • neither partner self-identifies as MSM • Power relationship between HCP and client is intensified; provider as gate-keeper who must give ongoing “approval” Development of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Etiological -

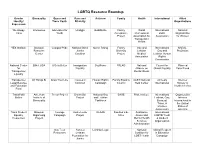

Lgbt Resource Roundup

LGBTQ Resource Roundup Gender Bisexuality Queer and Race and Activism Family Health International Allied Identity/ Trans Youth Ethnicity Organizations Expression We Happy Interweave Advocates for Unid@s GetEQUAL Family World International National Trans Youth Acceptance Professional LGBT Organization Project Association for Association for Women Transgender Health YES Institute Bisexual Campus Pride National Black Queer Rising Family Gay and International NARAL- Resource Justice Diversity Lesbian Gay and ProChoice Center Coalition Project Medical Lesbian Human Association Rights Commission National Center BiNet USA It Gets Better Immigration SoulForce PFLAG National Council for Planned for Equality Alliance on Global Equality Parenthood Transgender Mental Illness Equality Transgender All Things Bi Draw Your Line Causes in Human Rights Family Equality GLBT National Amnesty Intersex Legal Defense Common Campaign Council Help Center International Society of and Education North America Fund TransFaith American Trevor Project Brown Boi National Gay SAGE Pride Institute International Organization Online Institute of Project and Lesbian Lesbian, Gay, Intersex Bisexuality Taskforce Bisexual, International in Trans, & the United Intersex States of Association America Trans Student Bisexual Courage Audre Lorde GLAAD Families Like Substance International Equality Organizing Campaign Project Mine Abuse and LGBTQ Youth Resources Project Mental Health & Student Services Organization Administration Gay Teen Astraea Lambda Legal National Global Respect -

Identities That Fall Under the Nonbinary Umbrella Include, but Are Not Limited To

Identities that fall under the Nonbinary umbrella include, but are not limited to: Agender aka Genderless, Non-gender - Having no gender identity or no gender to express (Similar and sometimes used interchangeably with Gender Neutral) Androgyne aka Androgynous gender - Identifying or presenting between the binary options of man and woman or masculine and feminine (Similar and sometimes used interchangeably with Intergender) Bigender aka Bi-gender - Having two gender identities or expressions, either simultaneously, at different times or in different situations Fluid Gender aka Genderfluid, Pangender, Polygender - Moving between two or more different gender identities or expressions at different times or in different situations Gender Neutral aka Neutral Gender - Having a neutral gender identity or expression, or identifying with the preference for gender neutral language and pronouns Genderqueer aka Gender Queer - Non-normative gender identity or expression (often used as an umbrella term with similar scope to Nonbinary) Intergender aka Intergendered - Having a gender identity or expression that falls between the two binary options of man and woman or masculine and feminine Neutrois - Belonging to a non-gendered or neutral gendered class, usually but not always used to indicate the desire to hide or remove gender cues Nonbinary aka Non-binary - Identifying with the umbrella term covering all people with gender outside of the binary, without defining oneself more specifically Nonbinary Butch - Holding a nonbinary gender identity -

MANUFACTURING MORAL PANIC: Weaponizing Children to Undermine Gender Justice and Human Rights

MANUFACTURING MORAL PANIC: Weaponizing Children to Undermine Gender Justice and Human Rights Research Team: Juliana Martínez, PhD; Ángela Duarte, MA; María Juliana Rojas, EdM and MA. Sentiido (Colombia) March 2021 The Elevate Children Funders Group is the leading global network of funders focused exclusively on the wellbeing and rights of children and youth. We focus on the most marginalized and vulnerable to abuse, neglect, exploitation, and violence. Global Philanthropy Project (GPP) is a collaboration of funders and philanthropic advisors working to expand global philanthropic support to advance the human rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) people in the Global1 South and East. TABLE OF CONTENTS Glossary ...................................................................................... 4 Acronyms .................................................................................................. 4 Definitions ................................................................................................. 5 Letter from the Directors: ......................................................... 8 Executive Summary ................................................................... 10 Report Outline ..........................................................................................13 MOBILIZING A GENDER-RESTRICTIVE WORLDVIEW .... 14 The Making of the Contemporary Gender-Restrictive Movement ................................................... 18 Instrumentalizing Cultural Anxieties ......................................... -

INTERRUPTING HETERONORMATIVITY Copyright 2004, the Graduate School of Syracuse University

>>>>>> >>>>>> INTERRUPTING HETERONORMATIVITY Copyright 2004, The Graduate School of Syracuse University. Portions of this publication may be reproduced with acknowledgment for educational purposes. For more information about this publication, contact the Graduate School at Syracuse University, 423 Bowne Hall, Syracuse, New York 13244. >> contents Acknowledgments................................................................................... i Vice Chancellor’s Preface DEBORAH A. FREUND...................................................................... iii Editors’ Introduction MARY QUEEN, KATHLEEN FARRELL, AND NISHA GUPTA ............................ 1 PART ONE: INTERRUPTING HETERONORMATIVITY FRAMING THE ISSUES Heteronormativity and Teaching at Syracuse University SUSAN ADAMS.............................................................................. 13 Cartography of (Un)Intelligibility: A Migrant Intellectual’s Tale of the Field HUEI-HSUAN LIN............................................................................ 21 The Invisible Presence of Sexuality in the Classroom AHOURA AFSHAR........................................................................... 33 LISTENING TO STUDENTS (Un)Straightening the Syracuse University Landscape AMAN LUTHRA............................................................................... 45 Echoes of Silence: Experiences of LGBT College Students at SU RACHEL MORAN AND BRIAN STOUT..................................................... 55 The Importance of LGBT Allies CAMILLE BAKER............................................................................ -

The Gendered Masks We Wear So Well: the Issues of Being LGBT Or Non-Binary in High

Arcadia University ScholarWorks@Arcadia Faculty Curated Undergraduate Works Undergraduate Research 4-11-2018 The Gendered Masks We Wear So Well: The sI sues of Being LGBT or Non-Binary in High School Conner Davis [email protected] Arcadia University has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits ouy . Your story matters. Thank you. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.arcadia.edu/undergrad_works Part of the Educational Sociology Commons, and the Gender and Sexuality Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Conner, "The Gendered Masks We Wear So Well: The sI sues of Being LGBT or Non-Binary in High School" (2018). Faculty Curated Undergraduate Works. 53. https://scholarworks.arcadia.edu/undergrad_works/53 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research at ScholarWorks@Arcadia. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Curated Undergraduate Works by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@Arcadia. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Davis 1 The Gendered Masks We Wear So Well: The Issues of Being LGBT or Non-Binary in High School Conner J. Davis Arcadia University Davis 2 The Gendered Masks We Wear So Well: The Issues of Being LGBT or Non-Binary in High School By examining theories, doing a review of the literature, and providing arguments, the contents of this paper analyze multiple aspects of the modern binary gender system in high school, as well as teenage sexuality performances. This paper brings together research involving different schools from different areas, and explains why and how LGBT and gender non-binary students are oppressed in classes, by the curriculum, and in socialization between students. -

Concepts & Categories of LGBTQA+ Identities

Concepts & Categories of LGBTQA+ Identities This partial list of terms provides basic information to support further discussion and reading. Language is constantly changing; we encourage you to continue researching. Please note all terms should be chosen by a person for themselves. Allyship: The practice of self educating about Coming out: Coming to terms with one’s sexual heterosexism and cisgenderism, educating others, and orientation or gender identity. Can also mean stating actively supporting LGBTQA+ individuals and causes. openly that one is lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, Allyship is practiced both by cisgender and straight queer, and/or asexual. The term is usually used by people who support and advocate for the rights of members of the LGBTQA+ community, and LGBTQA+ people and by LGBTQA+ people who advocate heterosexual and cisgender people can experience a across communities. While the term “ally” implies a similar process of coming to terms with their identity as complete identity, “allyship” is an ongoing process. an ally. Asexual: A term people may use to describe their Gay: A term people may use to describe their identity experience of little to no sexual attraction to people of as a man whose romantic, emotional, physical, and/or any gender. Asexuality is a sexual orientation, and is not sexual attractions are to men. This term is also the same as celibacy or abstinence. There is a great sometimes claimed by lesbians and bisexual people. diversity in how members of the asexual community experience sexual and romantic attraction, desire, Gender & Gender-Inclusive Pronouns: A arousal, and relationships. pronoun is a part of speech that takes the place of other nouns. -

Genders & Sexualities Terms

GENDERS & SEXUALITIES TERMS All terms should be evaluated by your local community to determine what best fits. As with all language, the communities that utilize these and other words may have different meanings and reasons for using different terminology within different groups. Agender: a person who does not identify with a gender identity or gender expression; some agender-identifying people consider themselves gender neutral, genderless, and/or non- binary, while some consider “agender” to be their gender identity. Ally/Accomplice: a person who recognizes their privilege and is actively engaged in a community of resistance to dismantle the systems of oppression. They do not show up to “help” or participate as a way to make themselves feel less guilty about privilege but are able to lean into discomfort and have hard conversations about being held accountable and the ways they must use their privilege and/or social capital for the true liberation of oppressed communities. Androgynous: a person who expresses or presents merged socially-defined masculine and feminine characteristics, or mainly neutral characteristics. Asexual: having a lack of (or low level of) sexual attraction to others and/or a lack of interest or desire for sex or sexual partners. Asexuality exists on a spectrum from people who experience no sexual attraction nor have any desire for sex, to those who experience low levels of sexual attraction and only after significant amounts of time. Many of these different places on the spectrum have their own identity labels. Another term used within the asexual community is “ace,” meaning someone who is asexual.