Queer Feminine Disidentificatory Orientations: Occupying Liminal Spaces of Queer Fem(Me)Inine (Un)Belonging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Boi, Boss Bitch

Black Boi, Boss Bitch Lauryn Hill 18 Jan 1995 - 26 Sep 1998 BLACK QUEER LOOKS Y todo comenzo bailando.... 27 Oct 1998 “Y todo comenzo bailando”...The earliest memories I can recall of my existence are festive. 20 Pound Pots of pernil & pigfeet. Pasteles, Gandulez, Guinea, Pollo Guisado. Habichuelas. 5 different types of beans & 5 different dishes on one plate. Even if only 4 niggas pulled up to the crib, abuela was always cooking for 40. The image of her red lipstick stain on hefty glasses of Budweiser that once contained Goya olives is forever etched in my mind. This was that poor boricua family that stored rice & beans in “I Can’t Believe it’s Not Butter” containers.The kind of family that blasted Jerry Rivera’s & Frankie Ruiz voices over dollar-store speakers. The kind that prized Marc Anthony, Hector LaVoe, El Gran Combo, La India, Tito Rojas. Victor Manuelle. Salsa Legends that put abuela's feet to work. My cousin Nina & her wife Iris who sparked their Ls in the bathroom, waving around floor length box braids, and bomb ass butch-queen aesthetics. “Pero nino, you hoppin on the cyph?. Uncle Negro or “Black”as we called him for his rich dark-skin, stay trying to wife my mom’s friends. 7:11 pm. 7 pounds 8 oz. October 27th. Maybe it was the lucky 7. Maybe it was fated for them to welcome another, intensely-loving Scorpio into their home. Or maybe it was just another blissful evening in the barrio. Where Bottles of Henny would be popped, and cousins & aunts & uncles you didn’t even know you had would reappear. -

The Oxford Democrat : Vol. 70. No.52

The Oxford Democrat. 1903. NUMBER 52. VOLUME 70. SOUTH PARIS, MAINE, TUESDAY, DECEMBER 29, KH tiMh'.l lo; ili l 'y. oners, but Beverley soon suspected tl tt rutiler item, who was coining out 01 never fails. But he'll tell Clark to eta.v JUNKS, Fruit Marketing and Storage. *«W>4^3*4HfcHêHîMlHWHfr^ Furii «worth was on his guard in a C. THE a "tralllc In hah," ae the terrible bu-tl- u cabin nut far away, beard and knew where he is, and Vigo can do no more." ^ AMONG FARMERS. Some of the most and twin!;iing. lie set his jaw and uttered preening impor- ness had been named, was going on. the voice. What effect Helm's hold and appar- & Machinist, in- a< I!· htnh.· Smith tant relating to the fri\it f nil ugly oath: then qiii-k MA1NK. questions miH"î Savages came In from far away with Ho. lio. little cried artless talk h:id upon Hamilton's SOUTH PARIS, are those that out of the y4"i«P my lady!" ently at the with "SFLKD THIS PLOW." dustry grow he struck siucwlse pistol of general machinery, steam en in horticulture to scalps yet scarcely dry dangling at Adrien ne's captor in a breezy, jocund mind Is not recorded, hut the meager Manufacturer anil tools., .present tendency pro- his blade. It was a move which might mill work, spool machinery their belis. It made the Vir- "You wouldn't run over u facts at command show that ,'lties, drille made and duce each fruit in that section where it #| young tone. -

Sexual Orientation and Trans Sexuality 101

Sexual Orientation and Trans Sexuality 101 Michael L Krychman MD Executive Director of the Southern California Center for Sexual Health and Survivorship Medicine Associate Clinical Professor UCI AASECT Certified Sexual Counselor Developmental Sexuality Review • Things do go wrong! – Chromosomal – Hormonal Gender Identity & Sexual Orientation are Different! • Every individual has a – biological sex – a gender identity – a sexual orientation. – (All can be considered fluid!) • Being transgender does not mean you’re gay and being gay does not mean you’re transgender. – There is overlap, in part because gender variance is often seen in gay context. – Masculine females and feminine males are often assumed to be gay; – “Anti-gay” discrimination and violence often targets gender expression, not sexuality Anatomy does not determine sexual orientation Homophobia is different than Transphobia Case: Ego Dystonic Bisexual Transgender Male becoming a female Has both a male and female partner Parts: heterosexual Identity: homosexual Gender Identity & Sexual Orientation are Different! • Coming out as gay is different than coming out as transexual • Trans people are often marginalized in G/L context. • How do we apply cultural competency lessons that apply around heterosexism to gender variance? • CDC categorizes MTFs and partners as MSM; • neither partner self-identifies as MSM • Power relationship between HCP and client is intensified; provider as gate-keeper who must give ongoing “approval” Development of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Etiological -

Posting Selfies and Body Image in Young Adult Women: the Selfie Paradox

Posting selfies and body image in young adult women: The selfie paradox. Item Type Article Authors Grogan, Sarah; Rothery, Leonie; Cole, Jenny; Hall, Matthew Citation Grogan, S., Rothery, L., Cole, J. & Hall, M. (2018). Posting selfies and body image in young adult women: The selfie paradox. Journal of Social Media in Society, 7(1), 15-36. Publisher Tarleton State University Journal The Journal of Social Media in Society Download date 28/09/2021 07:51:29 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10545/622743 The Journal of Social Media in Society Spring 2018, Vol. 7, No. 1, Pages 15-36 thejsms.org Posting Selfies and Body Image in Young Adult Women: The Selfie Paradox Sarah Grogan1*, Leonie Rothery1, Jennifer Cole1, and Matthew Hall2 1Department of Psychology, Manchester Metropolitan University, 53 Bonsall Street, Manchester, UK, M15 6GX. 2Faculty of Life & Health Sciences, Ulster University, Cromore Road, Coleraine, BT52 1SA; College of Business, Law & Social Sciences, University of Derby, Kedleston Rd, Derby DE22 1GB. *Corresponding Author: [email protected], (044)1612472504. This exploratory study was designed to investigate Women differentiated between their “unreal,” how young women make sense of their decision to digitally manipulated online selfie identity and their post selfies, and perceived links between selfie “real” identity outside of Facebook and Instagram. posting and body image. Eighteen 19-22 year old Bodies were expected to be covered, and sexualised British women were interviewed about their selfies were to be avoided. Results challenge experiences of taking and posting selfies, and conceptualisations of women as empowered and self- interviews were analysed using inductive thematic determined selfie posters; although women sought to analysis. -

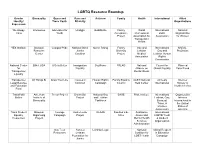

Lgbt Resource Roundup

LGBTQ Resource Roundup Gender Bisexuality Queer and Race and Activism Family Health International Allied Identity/ Trans Youth Ethnicity Organizations Expression We Happy Interweave Advocates for Unid@s GetEQUAL Family World International National Trans Youth Acceptance Professional LGBT Organization Project Association for Association for Women Transgender Health YES Institute Bisexual Campus Pride National Black Queer Rising Family Gay and International NARAL- Resource Justice Diversity Lesbian Gay and ProChoice Center Coalition Project Medical Lesbian Human Association Rights Commission National Center BiNet USA It Gets Better Immigration SoulForce PFLAG National Council for Planned for Equality Alliance on Global Equality Parenthood Transgender Mental Illness Equality Transgender All Things Bi Draw Your Line Causes in Human Rights Family Equality GLBT National Amnesty Intersex Legal Defense Common Campaign Council Help Center International Society of and Education North America Fund TransFaith American Trevor Project Brown Boi National Gay SAGE Pride Institute International Organization Online Institute of Project and Lesbian Lesbian, Gay, Intersex Bisexuality Taskforce Bisexual, International in Trans, & the United Intersex States of Association America Trans Student Bisexual Courage Audre Lorde GLAAD Families Like Substance International Equality Organizing Campaign Project Mine Abuse and LGBTQ Youth Resources Project Mental Health & Student Services Organization Administration Gay Teen Astraea Lambda Legal National Global Respect -

L Brown Presentation

Health Equity Learning Series Beyond Service Provision and Disparate Outcomes: Disability Justice Informing Communities of Practice HEALTH EQUITY LEARNING SERIES 2016-17 GRANTEES • Aurora Mental Health Center • Northwest Colorado Health • Bright Futures • Poudre Valley Health System • Central Colorado Area Health Education Foundation (Vida Sana) Center • Pueblo Triple Aim Corporation • Colorado Cross-Disability Coalition • Rural Communities Resource Center • Colorado Latino Leadership, Advocacy • Southeast Mental Health Services and Research Organization • The Civic Canopy • Cultivando • The Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and • Eagle County Health and Human Transgender Community Center of Services Colorado • El Centro AMISTAD • Tri-County Health Network • El Paso County Public Health • Warm Cookies of the Revolution • Hispanic Affairs Project • Western Colorado Area Health Education Center HEALTH EQUITY LEARNING SERIES Lydia X. Z. Brown (they/them) • Activist, writer and speaker • Past President, TASH New England • Chairperson, Massachusetts Developmental Disabilities Council • Board member, Autism Women’s Network ACCESS NOTE Please use this space as you need or prefer. Sit in chairs or on the floor, pace, lie on the floor, rock, flap, spin, move around, step in and out of the room. CONTENT/TW I will talk about trauma, abuse, violence, and murder of disabled people, as well as forced treatment and institutions, and other acts of violence, including sexual violence. Please feel free to step out of the room at any time if you need to. BEYOND SERVICE -

Impact of a Psychology of Masculinities Course on Women's Attitudes Toward Male Gender Roles

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Winter 3-25-2015 Impact of a Psychology of Masculinities Course on Women's Attitudes toward Male Gender Roles Sylvia Marie Ferguson Kidder Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Gender and Sexuality Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Kidder, Sylvia Marie Ferguson, "Impact of a Psychology of Masculinities Course on Women's Attitudes toward Male Gender Roles" (2015). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2210. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2207 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Impact of a Psychology of Masculinities Course on Women’s Attitudes toward Male Gender Roles by Sylvia Marie Ferguson Kidder A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Psychology Thesis Committee: Eric Mankowski, Chair Kerth O’Brien Kimberly Kahn Portland State University 2015 © 2015 Sylvia Marie Ferguson Kidder i Abstract Individuals are involved in an ongoing construction of gender ideology from two opposite but intertwined directions: they experience pressure to follow gender role norms, and they also participate in the social construction of these norms. An individual’s appraisal, positive or negative, of gender roles is called a “gender role attitude.” These lie on a continuum from traditional to progressive. -

A Metrosexual Eye on Queer Guy.” GLQ: a Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 11, No

2005 “A Metrosexual Eye on Queer Guy.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 11, no. 1: 112-17.t/1/1/15 QUEER TV STYLE 113 Manhattan wine bars and clubs. The key to the program is that the potential met- rosexual can be found in the suburban reaches of the tri-state area (New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut), awaiting his transformation from ordinary man into hipster. Essentially, Queer Eye’s queer management consultants descend on him from Gotham, charged with increasing his marketability as husband, father, and (more silently) employee. What were the preconditions for the emergence of the metrosexual, of Queer Eye, and of such makeovers? The 1980s saw two crucial conferences that helped shift the direction of global advertising: “Classifying People” and “Reclassifying People.” Traditional ways of understanding consumers—by race, gender, class, and region—were sup- plemented by categories of self-display, with market researchers dubbing the 1990s the decade of the “new man.”3 Lifestyle and psychographic research became cen- tral, with consumers divided among “moralists,” “trendies,” “the indifferent,” “working-class puritans,” “sociable spenders,” and “pleasure seekers.” Men were subdivided into “pontificators,” “self-admirers,” “self-exploiters,” “token triers,” “chameleons,” “avant-gardicians,” “sleepwalkers,” and “passive endurers.”4 These new ways of thinking about consumers and audiences were linked to new ways of thinking about—and policing—employees. By 1997, 43 percent of U.S. men up to their late fifties disclosed dissatisfaction with their appearance, compared to 34 percent in 1985 and 15 percent in 1972. Why? Because the middle-class U.S. -

Color-Conscious Multicultural Mindfulness (Ccmm): an Investigation of Counseling Students and Pre-Licensed Counselors

COLOR-CONSCIOUS MULTICULTURAL MINDFULNESS (CCMM): AN INVESTIGATION OF COUNSELING STUDENTS AND PRE-LICENSED COUNSELORS By EMILIE AYN LENES A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2018 © 2018 Emilie Ayn Lenes Dedicated to you, the reader in this moment right now. May we evoke curiosity and compassion with one another. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Synchronicity and grace have guided my way, and I thank the divinely orchestrated fabric that somehow enabled this dissertation to come to completion. Despite all the literature I have read, and the profound education that I have received from an incalculable number of exceptional people, I know that I still have many areas of development. I am on a lifelong journey of dismantling my own social conditioning. Our American society has been built upon racist roots and oppressive systems that advantage some groups of people and marginalize others. Awareness of this has given me a sense of ethical responsibility to be on a collective team of people who are working towards tikkun olam. This dissertation has drawn upon interactions throughout my lifetime, but especially over the past decade at the PACE Center for Girls. Individual and group conversations continuously enlighten me, as well as participation in multicultural and/or mindfulness conferences and trainings over the years. I acknowledge those whose insights have been integrated on a level beyond my ability to always remember precise attributions. Undoubtedly, there is someone who may be reading this right now, who contributed in some way(s) that I neglect to mention. -

Anarcha-Feminism.Pdf

mL?1 P 000 a 9 Hc k~ Q 0 \u .s - (Dm act @ 0" r. rr] 0 r 1'3 0 :' c3 cr c+e*10 $ 9 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.... 1 Anarcha-Feminism: what it is and why it's important.... 4 Anarchism. Feminism. and the Affinity Group.... 10 Anarcha-Feminist Practices and Organizing .... 16 Global Women's Movements Through an anarchist Lens ..22 A Brief History of Anarchist Feminism.... 23 Voltairine de Cleyre - An Overview .... 26 Emma Goldman and the benefits of fulfillment.... 29 Anarcha-Feminist Resources.... 33 Conclusion .... 38 INTRODUCTION This zine was compiled at the completion of a quarters worth of course work by three students looking to further their understanding of anarchism, feminism, and social justice. It is meant to disseminate what we have deemed important information throughout our studies. This information may be used as a tool for all people, women in particular, who wish to dismantle the oppressions they face externally, and within their own lives. We are two men and one woman attempting to grasp at how we can deconstruct the patriarchal foundations upon which we perceive an unjust society has been built. We hope that at least some component of this work will be found useful to a variety of readers. This Zine is meant to be an introduction into anarcha-feminism, its origins, applications, and potentials. Buen provecho! We acknowledge that anarcha-feminism has historically been a western theory; thus, unfortunately, much of this ziners content reflects this limitation. However, we have included some information and analysis on worldwide anarcha-feminists as well as global women's struggles which don't necessarily identify as anarchist. -

GENDER STUDIES NEWSLETTER Spring 2017 Letter from Director

GENDER STUDIES NEWSLETTER Spring 2017 Letter from Director As we move into the Spring and I take stock of our accomplishments for the 2016-2017 year, I am truly astonished and so very proud. In this newsletter, I have attempted to cover the wide range of gender-related events and advancements on campus, and frankly, I ran out of room. For such a small campus to create such a massive, wide-reaching impact brings me joy. We have a truly committed faculty and hardworking students who are determined to open the theories of our classrooms to the wider world. Imagine what we can accomplish if we keep it up. We can change the world. We are changing the world. Given the divisiveness of recent political events, finding hope and strength in our work is imperative. So is solidarity. Here’s to a refreshing spring semester and another round of transformative gender programming. - Corey L. Wrenn, PhD DID YOU KNOW? Many Gender Studies minors also major or minor in SOCIOLOGY! Monmouth’s Gender Studies Program is a housed within the Sociology Department. Speak with a faculty member today about what a degree in Sociology and/or Gender Studies can do for your life after Monmouth. NEWS Monmouth University Gender Studies Faculty and Affiliates Pen Letter to The Outlook The following is a reprint of a letter printed in a November issue of The Outlook, Monmouth’s student newspaper. As concerned educators, we are reaching out to students, faculty, administrators, staff, and the extended campus community to encourage open and respectful dialogue in this post-election period. -

Cultural and Social Implications of Metrosexual Mode

Journal of Fashion Business Vol. 10, No. 3, pp.117~128(2006) Cultural and Social Implications of Metrosexual Mode Oh, Yun-Jeong* ․ Cho, Kyu-Hwa Candidate for Ph.D., Dept. of Clothing and Textiles, Ewha Womans University* Professor,Dept.ofClothingandTextiles,EwhaWomansUniversity Abstract The purpose of this study was to understand changes of the current young generation's lifestyle, aesthetic attitude for an appearance, and way of thinking by making a close investigation into metrosexual, the recent mode, and find out its culturalandsocial implications. As a method of the study, the literature and the Internet datawerereviewed. Articles from newspapers, magazines and the Internet were chosen roughly from the year 2000 to now because metrosexual mode remarkably boomed before and after 2000. Books related to the theory on the mode in a costume culture were referred. Also, articles in daily newspapers which dealt with cultural and social issues were reviewed, fashion magazines for men such as Esquire and GQ showing the new trend in men's lifestyle and fashion were examined, and the Internet providing us the latest news from cultural and social topics to fashion trends were investigated. The backgrounds of the rise of metrosexualmodewerea collapse of stereotypes in various fields, spread of lookism in a visual image period, extension of commercialism, and expansion of men's character casual trend. Metrosexual was defined as an urban male with a strong aesthetic sense who spends a great deal of time and money on his appearance and lifestyle. His fashion style was characterized by slim and flowing silhouette, feminine and luxurious materials such as transparent chiffon, silk and cotton with a light and soft touch, and a knitted wear with a flowing line,awide variety of vivid and pastel colors, floral and geometric patterns, and the decorative details likelace,beads,embroidery,andfur.Fromspreadofthismode,twocultural and social implications were extracted.