Essentialist Abstraction, by Jeffrey Strayer University of Leeds, in October 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy of Music Education

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Honors Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2017 Philosophy of Music Education Mary Elizabeth Barba Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/honors Part of the Music Education Commons, and the Music Pedagogy Commons Recommended Citation Barba, Mary Elizabeth, "Philosophy of Music Education" (2017). Honors Theses and Capstones. 322. https://scholars.unh.edu/honors/322 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Philosophy of Music Education Mary Barba Dr. David Upham December 9, 2016 Barba 1 Philosophy of Music Education A philosophy of music education refers to the value of music, the value of teaching music, and how to practically utilize those values in the music classroom. Bennet Reimer, a renowned music education philosopher, wrote the following, regarding the value of studying the philosophy of music education: “To the degree we can present a convincing explanation of the nature of the art of music and the value of music in the lives of people, to that degree we can present a convincing picture of the nature of music education and its value for human life.”1 In this thesis, I will explore the philosophies of Emile Jacques-Dalcroze, Carl Orff, Zoltán Kodály, Bennett Reimer, and David Elliott, and suggest practical applications of their philosophies in the orchestral classroom, especially in the context of ear training and improvisation. -

Gestural Abstraction in Australian Art 1947 – 1963: Repositioning the Work of Albert Tucker

Gestural Abstraction in Australian Art 1947 – 1963: Repositioning the Work of Albert Tucker Volume One Carol Ann Gilchrist A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art History School of Humanities Faculty of Arts University of Adelaide South Australia October 2015 Thesis Declaration I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University‟s digital research repository, the Library Search and also through web search engines, unless permission has been granted by the University to restrict access for a period of time. __________________________ __________________________ Abstract Gestural abstraction in the work of Australian painters was little understood and often ignored or misconstrued in the local Australian context during the tendency‟s international high point from 1947-1963. -

Gce History of Art Major Modern Art Movements

FACTFILE: GCE HISTORY OF ART MAJOR MODERN ART MOVEMENTS Major Modern Art Movements Key words Overview New types of art; collage, assemblage, kinetic, The range of Major Modern Art Movements is photography, land art, earthworks, performance art. extensive. There are over 100 known art movements and information on a selected range of the better Use of new materials; found objects, ephemeral known art movements in modern times is provided materials, junk, readymades and everyday items. below. The influence of one art movement upon Expressive use of colour particularly in; another can be seen in the definitions as twentieth Impressionism, Post Impressionism, Fauvism, century art which became known as a time of ‘isms’. Cubism, Expressionism, and colour field painting. New Techniques; Pointilism, automatic drawing, frottage, action painting, Pop Art, Neo-Impressionism, Synthesism, Kinetic Art, Neo-Dada and Op Art. 1 FACTFILE: GCE HISTORY OF ART / MAJOR MODERN ART MOVEMENTS The Making of Modern Art The Nine most influential Art Movements to impact Cubism (fl. 1908–14) on Modern Art; Primarily practised in painting and originating (1) Impressionism; in Paris c.1907, Cubism saw artists employing (2) Fauvism; an analytic vision based on fragmentation and multiple viewpoints. It was like a deconstructing of (3) Cubism; the subject and came as a rejection of Renaissance- (4) Futurism; inspired linear perspective and rounded volumes. The two main artists practising Cubism were Pablo (5) Expressionism; Picasso and Georges Braque, in two variants (6) Dada; ‘Analytical Cubism’ and ‘Synthetic Cubism’. This movement was to influence abstract art for the (7) Surrealism; next 50 years with the emergence of the flat (8) Abstract Expressionism; picture plane and an alternative to conventional perspective. -

The Art of Hans Arp After 1945

Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers The Art of Hans Arp after 1945 Volume 2 Edited by Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers Volume 2 The Art of Arp after 1945 Edited by Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger Table of Contents 10 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning 12 Foreword Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger 16 The Art of Hans Arp after 1945 An Introduction Maike Steinkamp 25 At the Threshold of a New Sculpture On the Development of Arp’s Sculptural Principles in the Threshold Sculptures Jan Giebel 41 On Forest Wheels and Forest Giants A Series of Sculptures by Hans Arp 1961 – 1964 Simona Martinoli 60 People are like Flies Hans Arp, Camille Bryen, and Abhumanism Isabelle Ewig 80 “Cher Maître” Lygia Clark and Hans Arp’s Concept of Concrete Art Heloisa Espada 88 Organic Form, Hapticity and Space as a Primary Being The Polish Neo-Avant-Garde and Hans Arp Marta Smolińska 108 Arp’s Mysticism Rudolf Suter 125 Arp’s “Moods” from Dada to Experimental Poetry The Late Poetry in Dialogue with the New Avant-Gardes Agathe Mareuge 139 Families of Mind — Families of Forms Hans Arp, Alvar Aalto, and a Case of Artistic Influence Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen 157 Movement — Space Arp & Architecture Dick van Gameren 174 Contributors 178 Photo Credits 9 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning Hans Arp’s late work after 1945 can only be understood in the context of the horrific three decades that preceded it. The First World War, the catastro- phe of the century, and the Second World War that followed shortly thereaf- ter, were finally over. -

ART 129 New Masters' Aesthetics and Techniques

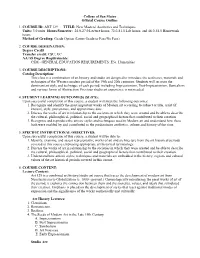

College of San Mateo Official Course Outline 1. COURSE ID: ART 129 TITLE: New Masters' Aesthetics and Techniques Units: 3.0 units Hours/Semester: 24.0-27.0 Lecture hours; 72.0-81.0 Lab hours; and 48.0-54.0 Homework hours Method of Grading: Grade Option (Letter Grade or Pass/No Pass) 2. COURSE DESIGNATION: Degree Credit Transfer credit: CSU; UC AA/AS Degree Requirements: CSM - GENERAL EDUCATION REQUIREMENTS: E5c. Humanities 3. COURSE DESCRIPTIONS: Catalog Description: This class is a combination of art history and studio art designed to introduce the aesthetics, materials and techniques of the Western modern period of the 19th and 20th centuries. Students will recreate the dominant art style and technique of each period, including Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Surrealism and various forms of Abstraction. Previous studio art experience is not needed. 4. STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOME(S) (SLO'S): Upon successful completion of this course, a student will meet the following outcomes: 1. Recognize and identify the most important works of Modern art according to subject or title, artist (if known), style, provenance, and approximate date. 2. Discuss the works of art in relationship to the societies in which they were created and be able to describe the cultural, philosophical, political, social and geographical factors that contributed to their creation. 3. Recognize and reproduce the artistic styles and techniques used in Modern art and understand how these both were enabled by and contributed to the predominate aesthetics, culture and history of the time. 5. SPECIFIC INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES: Upon successful completion of this course, a student will be able to: 1. -

Rise of Modernism

AP History of Art Unit Ten: RISE OF MODERNISM Prepared by: D. Darracott Plano West Senior High School 1 Unit TEN: Rise of Modernism STUDENT NOTES IMPRESSIONISM Edouard Manet. Luncheon on the Grass, 1863, oil on canvas Edouard Manet shocking display of Realism rejection of academic principles development of the avant garde at the Salon des Refuses inclusion of a still life a “vulgar” nude for the bourgeois public Edouard Manet. Olympia, 1863, oil on canvas Victorine Meurent Manet’s ties to tradition attributes of a prostitute Emile Zola a servant with flowers strong, emphatic outlines Manet’s use of black Edouard Manet. Bar at the Folies Bergere, 1882, oil on canvas a barmaid named Suzon Gaston Latouche Folies Bergere love of illusion and reflections champagne and beer Gustave Caillebotte. A Rainy Day, 1877, oil on canvas Gustave Caillebotte great avenues of a modern Paris 2 Unit TEN: Rise of Modernism STUDENT NOTES informal and asymmetrical composition with cropped figures Edgar Degas. The Bellelli Family, 1858-60, oil on canvas Edgar Degas admiration for Ingres cold, austere atmosphere beheaded dog vertical line as a physical and psychological division Edgar Degas. Rehearsal in the Foyer of the Opera, 1872, oil on canvas Degas’ fascination with the ballet use of empty (negative) space informal poses along diagonal lines influence of Japanese woodblock prints strong verticals of the architecture and the dancing master chair in the foreground Edgar Degas. The Morning Bath, c. 1883, pastel on paper advantages of pastels voyeurism Mary Cassatt. The Bath, c. 1892, oil on canvas Mary Cassatt mother and child in flattened space genre scene lacking sentimentality 3 Unit TEN: Rise of Modernism STUDENT NOTES Claude Monet. -

Philosophy of Music Philosophy 365 Syllabus

Philosophy of Music Philosophy 365 Syllabus John Douard Texts: New Jersey Books will have the texts. The Imaginary Museum of Musical Works, by Lydia Goehr, Oxford University Press., ISBN: 9780195324785 Listening to Popular Music, or How I learned to stop worrying and love Led Zeppelin by Theodore Gracyk, U. of Michigan Press, ISBN: 978-0-472-06983-5 Improvisation: It’s Nature and Practice in Music, by Derek Bailey, Da Capo Press, ISBN: 978-0306805288 Derek Bailey: On the Edge: Video based on Improvisation: http://ubu.com/film/bailey.html I will also email a packet of papers on specific issues. ______________________________________________________________________________________________ In this course, we begin with a consideration of the concept of the musical work. We will then examine improvisational music: jazz, rock and hip hop; but also music generated as improvisations in the classical canon, Indian raga, and African indigenous music. Most courses on the philosophy of music focus on “classical” or “art” music. These terms usually are used in an ethnocentric way to refer to formal Western music, and it is in that context in which the concept of the musical work evolved in the early 19th century. A focus on improvisation will permit an interrogation of the concept of a musical work, by setting it against the essentially imperfect productions of improvisations. We will conclude with a conversation about the politics of music and the role of the audience in musical production. The purpose of this course is to deepen your understanding of music by reflecting on fundamental philosophical questions, but also to deepen your philosophical understanding by examining questions about an ubiquitous human practice. -

Kant Expressive Theory Music

Kant’s Expressive Theory of Music Samantha Matherne Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism (2014, pre-print) Abstract: Several prominent philosophers of art (e.g., Kivy, Dahlhaus, Schueller) have worried whether Kant has a coherent theory of music on account of two perceived tensions in his view. First, there appears to be a conflict between his formalist and expressive commitments. Second (and even worse), Kant defends seemingly contradictory claims about music being beautiful and merely agreeable, i.e., not beautiful. Against these critics, I show that Kant has a consistent view of music that reconciles these tensions. I argue that, for Kant, music can be experienced as either agreeable or beautiful depending upon the attitude we take towards it. Though we might be tempted to think he argues that we experience music as agreeable when we attend to its expressive qualities and as beautiful when we attend to its formal properties, I demonstrate that he actually claims that we are able to judge music as beautiful only if we are sensitive to the expression of emotion through musical form. With this revised understanding of Kant’s theory of music in place, I conclude by sketching a Kantian solution to a central problem in the philosophy of music: given that music is not sentient, how can it express emotion? §1. Introduction As philosophers like Peter Kivy and Stephen Davies have emphasized, one of the central issues in the philosophy of music is the problem of expression.1 Frequently when we hear a piece of instrumental music, we describe it as expressing an emotion, e.g., Beethoven’s ‘Eroica’ symphony sounds triumphant or Chopin’s Étude in E Major (Op. -

Musical Affects and the Life of Faith: Some Reflections on the Religious Potency of Music

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Asbury Theological Seminary Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers Volume 21 Issue 1 Article 2 1-1-2004 Musical Affects and the Life of Faith: Some Reflections on the Religious Potency of Music Mark Wynn Follow this and additional works at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy Recommended Citation Wynn, Mark (2004) "Musical Affects and the Life of Faith: Some Reflections on the Religious Potency of Music," Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers: Vol. 21 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy/vol21/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers by an authorized editor of ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. MUSICAL AFFECTS AND THE LIFE OF FAITH: SOME REFLECTIONS ON THE RELIGIOUS POTENCY OF MUSIC Mark Wynn The paper argues that the religious suggestiveness of music can be illumi nated by reference to a number of themes drawn from contemporary phi losophy of music, in particular the idea that the affective states expressed in music lack material objects, are often grasped "sympathetically," may escape verbalisation, and lack action-guiding content. Together these themes suggest that music may express, and enable its hearers to take on, an affectively laden "world-view." The paper explores the thought that such "attitudes" may be religiously important not only in setting the affec tive tone of our relationship to the world, but also in relationship to God. -

Editors' Introduction: Adorno, Music, Modernity

Editors' Introduction: Adorno, Music, Modernity The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Gordon, Peter E., and Alexander Rehding. 2016. “Editors’ Introduction: Adorno, Music, Modernity.” New German Critique 43 (3 129) (November): 1–4. doi:10.1215/0094033x-3625283. Published Version doi:10.1215/0094033X-3625283 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:34391749 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Editors’ Introduction: Adorno, Music, Modernity New German Critique: Special Issue on Adorno and Music Peter E. Gordon and Alex Rehding (Harvard University) “As a temporal art,” Adorno observed, “music is bound to the fact of succession and is hence as irreversible as time itself. By starting it commits itself to carrying on, to becoming something new, to developing. What we may conceive of as musical transcendence, namely, the fact that at any given moment it has become something and something other than it was, that points beyond itself—all that is no mere metaphysical imperative dictated by some external authority. It likes in the nature of music and will not be denied.”1 Such remarks serve to remind us once again that Adorno was at once a philosopher and a musicologist: amongst all the members of the Frankfurt School he possessed not only a sociological and social-theoretical awareness of the dialectical relation between music and society, but also an incomparable feel for the inner power of music. -

LOOKING for AMERICA, Another Excerpt from Ed Mccormack's

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2011 www.galleryandstudiomagazine.com VOL. 14 NO. 1 New York GALLERYSTUDIO SENATEDELLA! The New York Art World’s Controversial Gadfly, Robert Cenedella, Skewers the U.S. Senate plus: LOOKING FOR AMERICA, another excerpt from Ed McCormack’s memoir in progress HOODLUM HEART pg. 14 Norman Perlmutter “ORDINARY THINGS” “File Box,” Acrylic on Canvas, 24"x30" “File Box,” October 25 – November 8, 2011 Tues - Sun 2-7pm Artist’s Receptions: Thurs., Oct. 27 & Fri., Nov 4, 6-8pm 2/20 Gallery 220 West 16th Street, New York, NY 10011 212-807-8348 — www.220gallery.net TINA ROHRER Awash in Blue and Green Geometric acrylic paintings presenting color interactions and impresssions of movement “Accent Aqua II,” Acrylic, 18"x18" “Accent Aqua II,” Dates: October 4-October 29, 2011 Reception: Saturday, October 8, 4-6 PM :HVWWK6W1<& 7XHV6DWDPSP ZZZQRKRJDOOHU\FRP GALLERYSTUDIO SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2011 GS Highlights On the Cover: Cenedella Takes On The Teabaggers –– pg. 9 PLUS: Eloping to the tune of a Simon & Garfunkel song ... Living a La Boheme fantasy like incestuous siblings in a blue Sharyn Finnegan, pg. 8 collar family attic ... Starry-eyed on the brink of nuclear apocalypse ... the HOODLUM HEART saga continues –– pg.14 Joan Marie Kelly, pg. 20 Catherine de Saugy, pg. 21 Marcia Clark, Malka Inbal, pg. 7 Tina Rohrer, pg. 4 pg. 5 Subscribe to GALLERYSTUDIO GALLERYSTUDIO An International Art Journal $25 Subscription $20 for additional Gift Subscription $47 International $5 Back Issues PUBLISHED BY Mail check or Money Order to: ©EYE LEVEL, LTD. -

19Chronology of Works in Aesthetics and Philosophy Of

Chronology of 19 Works in Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art Darren Hudson Hick Notes on Selection This chronology, as with this Companion as a whole, focuses on those works that contribute to the Western tradition of aesthetics, and, beginning in the twentieth century, in the analytic current of thought within that tradition (as opposed to the Continental one). As with the history of Western philosophy in general, the study of philosophical problems in art and beauty dates back to the ancient period, and is infl uenced by the major philosophical and cultural move- ments through the centuries. Much of what survives from the ancient to the post-Hellenistic period does so in fragments or references. In cases where only fragments or references exist, and where dating these is especially problematic, the author or attributed author and (where available) his dates of birth and death are listed. Where works have not survived even as fragments, these are not listed. As well, much of what sur- vives up to the medieval period is diffi cult to date, and is at times of disputable attribution. In these cases, whatever information is available is listed. Aesthetics in the period between the ancients and the medievals tends to be dominated by adherence to Platonic, Aristotelian, and other theories rooted in the ancient period, and as such tends to be generally lacking in substantive the- oretical advancements. And while still heavily infl uenced by ancient thinking, works from the medieval period tend also to be heavily infl uenced by religious thinking, and so many issues pertaining to art and aesthetics are intertwined with issues of religion as “theological aesthetics.” Movements in art theory and aes- thetics in the Renaissance, meanwhile, were largely advanced by working artists, and so tend to be couched in observational or pedagogical approaches, rather than strictly theoretical ones.