Warren Judson Mead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Virginia's Karst

Introduction to Virginia’s Karst A presentation of The Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation’s Karst Program & Project Underground Karst - A landscape developed in limestone, dolomite, marble, or other soluble rocks and characterized by subsurface drainage systems, sinking or losing streams, sinkholes, springs, and caves. Cross-section diagram by David Culver, American University. Karst topography covers much of the Valley and Ridge Province in the western third of the state. Aerial photo of karst landscape in Russell County. Smaller karst areas also occur in the Cumberland Plateau, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain provinces. At least 29 counties support karst terrane in western Virginia. In western Virginia, karst occurs along slopes and in valleys between mountain ridges. There are few surface streams in these limestone valleys as runoff from mountain slopes disappears into the subsurface upon contact with the karst bedrock. Water flows underground, emerging at springs on the valley floor. Thin soils over fractured, cavernous limestone allow precipitation to enter the subsurface directly and rapidly, with a minimal amount of natural filtration. The purer the limestone, the less soil develops on the bedrock, leaving bare pinnacles exposed at the ground surface. Rock pinnacles may also occur where land use practices result in massive soil loss. Precipitation mixing with carbon dioxide becomes acidic as it passes through soil. Through geologic time slightly acidic water dissolves and enlarges the bedrock fractures, forming caves and other voids in the bedrock. Water follows the path of least resistance, so it moves through voids in rock layers, fractures, and boundaries between soluble and insoluble bedrock. -

A Magical Country : Stories from Appalachia

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2014 A magical country : stories from Appalachia. James Eric Leary 1977- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Appalachian Studies Commons, Folklore Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Leary, James Eric 1977-, "A magical country : stories from Appalachia." (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1754. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1754 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A MAGICAL COUNTRY: STORIES FROM APPALACHIA By James Eric Leary B.A. Eastern Kentucky University, 2001 M.A. University of Louisville, 2005 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2014 Copyright 2014 by James Leary All rights reserved A MAGICAL COUNTRY: STORIES FROM APPALACHIA By James Leary B.A., Eastern Kentucky University, 2001 M.A., University of Louisville, 2005 A Dissertation Approved on November 24, 2014 by the following Dissertation Committee: _________________________________ Dissertation Director Dr. Annette Allen _________________________________ Paul Griner _________________________________ Dr. -

Trenches in England Gazetteer Issue-01 Formatted.Xlsx

Site Name Parish/District County NGR Description Condition References Mapping & AP Comments WWII Comments Designation Associated Files Source Aps EC Curwen air photo of practice trenches in Barbican House, Levelled by plough and some areas of scrub but Lewes. Assocacited with visible on AP and should survive. Appears to Thundersbarrow Hill Shoreham by Sea East Sussex TQ 2250 0850 Shoreham Camp overlie earlier Celtic field system on Google Earth Chasseaud 2014: Fig 2 NMP Plot + Kitchener's Camps at Seaford: A Trenches associated with First World War Landscape on Aerial Seaford Camp Seaford Head East Sussex TV 4992 9830 Kitchener Army camp. Extant, though overgrown on Google Earth Skinner 2011, pg 28 Photographs by Skinner EH Report 27/2011 Practice trenches on the side of the neck and on top of the neck Appear to be extant. Likely to be associated with Alfriston Alfriston East Sussex TQ 50918 03129 of the valley. Canadian Infantry Chasseaud 2014, pg 173 & Fig 9 Appear to be extant although some areas Chailey Common Chailey East Sussex TQ 374 208 Maze of practice trenches. overgrown. Chasseaud 2014, pg 175 & Fig 9 Practice trenches shown on aerial Exceat Exceat East Sussex TV 533 982 photographs. Not visible. Chasseaud 2014, pg 176 & Fig 9 Practice trenches shown on aerial Polegate Polegate East Sussex TQ 608 047 photographs. Not visible. Chasseaud 2014, pg 180 & Fig 9 Practice trenches including a Appear to be extant although difficult to discern Poundgate, extensive trench system on between archaeological features and trackways Ashdown Forset Poundgate East Sussex TQ 48804 29028 Poundgate Spur. -

A History of Warren, Idaho: Mining, Race, and Environment

A HISTORY OF WARREN, IDAHO: MINING, RACE, AND ENVIRONMENT by Cletus R. Edmunson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Boise State University August 2012 © 2012 Cletus R. Edmunson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Cletus R. Edmunson Thesis Title: A History of Warren, Idaho: Mining, Race, and Environment Date of Final Oral Examination: 15 June 2012 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Cletus R. Edmunson, and they evaluated his presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. Todd Shallat, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Jill Gill, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Lisa Brady, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by Todd Shallat, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved for the Graduate College by John R. Pelton, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College. DEDICATION This thesis is the culmination of my own journey back into Warren’s past and is dedicated to the man who started me on this journey, my dad, John H. Edmunson. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the support of many people. The author wishes to express his deepest gratitude to all of the members of the History Department at Boise State University. The author acknowledges the inherent difficulties in helping someone attain their degree when they choose a rather circuitous route. -

Mining for Empire

MINING FOR EMPIRE: GOLD, AMERICAN ENGINEERS, AND TRANSNATIONAL EXTRACTIVE CAPITALISM, 1889-1914 by Jeffrey Michael Bartos A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana November 2018 ©COPYRIGHT by Jeffrey Michael Bartos 2018 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION In loving memory of Dr. Harold C. Fleming and Lt. Col. Walter H. King, USAF iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I owe a deep debt to many people who supported this dissertation from start to finish. My partner Molly has been patient with my absent-mindedness and perpetual state of stress, and Jasper and Lucy offer the finest creature comforts. My family has been incredibly supportive as well, even if they weren’t quite sure what I was researching. I could not have come to this point without the amazing intellectual community fostered by the historians of Montana State University. I owe particular gratitude to my doctoral committee, who have seen me through both a Master’s thesis and now to this point. Thanks to Dr. Billy G. Smith, Dr. Tim LeCain, Dr. Mary Murphy, Dr. Bob Rydell, and Dr. Michael Reidy. My fellow graduate students have similarly pushed me in my research and thinking, and I must acknowledge Dr. Cheryl Hendry, Dr. Gary Sims, Jen Dunn, Laurel Angell, Kelsey Matson, Clinton Colgrove, Reed Knappe, Alex Aston, Anthony Wood, Jill Falcon Mackin, Will Wright, and many others for their intellectual rigor and for the exchange of ideas and thinking around this project. Special thanks to Kerri Clement who was my primary reader and sounding board for ideas; whether we were floating down a river or swapping drafts, Kerri was critical in the intellectual formations of this work. -

Idaho (Mining Engineering)

IDAHO V. GILLERMAN, Idaho Geological Survey and E.H. BENNETT, retired Idaho Geological Survey Idaho’s mining and exploration in- FIG. 1 dustry had a great first half of the year Idaho nonfuel mineral production (USGS). in 2008 with high commodity prices and buoyant optimism, but activity started to slow down across-the-board in the fall as the nation’s economic downturn and tightening credit markets took its toll. In March, 2008, the gold price topped $32.15/g ($1,000/oz), silver neared 64 cents/g ($20/oz) and molybdenum took top honors as the state’s most valuable commodity with molybdenum oxide prices above $30/lb for much of the year. By December, molybdenum oxide was under $10/lb and the recession was in full swing. Precious metal prices have shown resilience as a hedge in uncertain times. Silver mining in north Idaho was hard hit as zinc and lead prices dropped 50 percent in the last half of 2008. Construction activity, especially Gold Hunter Main, or 30, vein off the 5,900 level of the residential, was down for most of 2008, and the aggregate- Lucky Friday Mine at Mullan. The mine produced 90 t related commodities suffered accordingly. Employment (2.9 million oz) of silver in 2008 at a cash cost of about 20 in Idaho’s mining sector, which had been rising since its cents/g ($6/oz) silver versus 96.4 t (3.1 million oz) in 2007 low point of 1,759 jobs in 2002, increased to nearly 2,800 at a negative cash cost of 2 cents/g (75 cents/oz ) due to jobs in 2008, according to the Idaho Division of Financial byproduct credits. -

Mcfails Cave, the Beginning of NSS Cave Ownership and Development of a Model for Interactive Cave Management

McFails Cave, the Beginning of NSS Cave Ownership and Development of a Model for Interactive Cave Management Fred D. Stone, PhD (NSS 6015) Hawaii Community College Hilo, HI 96760 Abstract At the 1965 NSS Convention in Indiana, the Board of Governors voted to ac- cept ownership of the first NSS cave property, McFails Cave in New York State. To do so, they had to change a long-standing NSS policy of non-ownership of caves. This paper will cover the series of events, some serendipitous and some planned, that led to the purchase of McFails Cave and it’s role in changing NSS cave ownership policy. I will also discuss the development of the management strategy, through establishment of the McFails Committee, as a successful model of interactive cave management. Description pushed in 1961, opening into 5 miles of mostly large passageway. The Main Passage, after nearly 3 The pit we know today as McFails Hole is lo- miles, and the Southeast Passage, after 2,000 feet, cated in a heavily glaciated karst terrain four miles are water filled. In both cases, diving has yielded (as the bat flies) northeast of Cobleskill in Scho- extensive additions with continuing water-filled harie County, New York. It is in a woodland of passage. The Northeast Passage, after over 7,000 maple, birch, beech, oak, and hemlock in the midst feet of fairly easy going, has more recently yielded of dairy farms and cropland. The woodland con- several thousand additional feet of difficult pas- tains several depressions and pits, with intermit- sage. Currently, McFails Cave has about 7 miles tent surface streams feeding into many of them, in- of explored passage. -

Development of Sinkholes Resulting from Man1 S Activities in the Eastern United States

U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 968 Development of Sinkholes Resulting From Man1 s Activities in the Eastern United States Development of Sinkholes Resulting 1 From Man S Activities in the Eastern United States By J. G. Newton U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 968 1987 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAUL HODEL, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Newton, John G., 1929- Development of sinkholes resulting from man's activities in the Eastern United States. (U.S. Geological Survey circular; 968) Bibliography: p. 40 Supt. of Docs. no.: I 19.4/2:968 1. Sinkholes-Southern States-Environmental aspects. 2. Sinkholes Northeastern States-Environmental aspects. 3. Sinkholes-Middle West-Environmental aspects. I. Title. II. Series: Geological Survey circular ; 968. GB609.2.N47 1986 624.1 '51 85-600298 Free on application to the Books and Open-File Reports Section, U.S. Geological Survey, Federal Center, Box 25425, Denver, CO 80225 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract -------------------------------------- 1 Causes and occurrence-Continued Introduction 1 Decline of water level-Continued Scope and objectives ----------------------- 2 Water-level fluctuations ----------------- 20 Area of study ----------------------------- 3 Induced recharge ----------------------- 24 Method of investigation -------------------- 5 Occurrence and size --------------------- 26 Acknowledgments -------------------------- 5 Construction ------------------------------ 28 Magnitude of sinkhole-related problems -

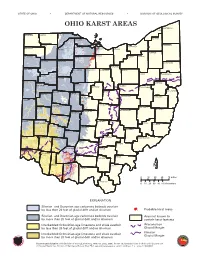

Map of Ohio Karst Areas

STA5&0'0)*0 t %&PARTMENT OF NA563"-3&4063$&4 t %*7*4*0/0'(&0LOGICAL SURVEY OHIO KARST AREAS ASHTABULA LAKE WILLIAMS FULTON LUCAS GEAUGA OTTAWA TRUMBULL HENRY CUYAHOGA SANDUSKY DEFIANCE ERIE WOOD LORAIN PORTAGE PAULDING HURON MEDINA SUMMIT SENECA PUTNAM HANCOCK MAHONING ASHLAND VAN WERT WYANDOT CRAWFORD RICHL AND WAYNE STARK COLUMBIANA ALLEN HARDIN MERCER CARROLL MARION AUGLAIZE HOLMES MORROW TUSCARAWAS JEFFERSON LOGAN KNOX SHELBY UNION COSHOCTON HARRISON DELAWARE DARKE LICKING CHAMPAIGN MIAMI GUERNSEY MUSKINGUM BELMONT FRANKLIN MADISON CLARK PREBLE FAIRFIELD PERRY MONTGOMERY NOBLE MONROE GREENE PICKAWAY MORGAN FAYETTE HOCKING BUTLER WARREN WASHINGTON CLINTON ROSS ATHENS HIGHLAND VINTON HAMILTON CLERMONT PIKE MEIGS JACKSON BROWN ADAMS GALLIA SCIOTO 0 10 20 30 40 miles LAWRENCE 0 10 20 30 40 50 kilometers EXPLANATION Silurian- and Devonian-age carbonate bedrock overlain by less than 20 feet of glacial drift and/or alluvium Probable karst areas Silurian- and Devonian-age carbonate bedrock overlain Area not known to by more than 20 feet of glacial drift and/or alluvium contain karst features Interbedded Ordovician-age limestone and shale overlain Wisconsinan by less than 20 feet of glacial drift and/or alluvium Glacial Margin Illinoian Interbedded Ordovician-age limestone and shale overlain Glacial Margin by more than 20 feet of glacial drift and/or alluvium Recommended citation: Ohio Division of Geological Survey, 1999 (rev. 2002, 2006), Known and probable karst in Ohio: Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Geological Survey Map EG-1, generalized page-size version with text, 2 p., scale 1:2,000,000. OHIO KARST AREAS Karst is a landform that develops on or in limestone, dolomite, or gypsum by dissolution and that is characterized by the presence of characteris- tic features such as sinkholes, underground (or internal) drainage through solution-enlarged fractures (joints), and caves. -

GIS Applied to Flood Mapping in Sinkhole Areas C. Warren

GIS Applied to Flood Mapping in Sinkhole Areas C. Warren Campbell, Ph.D., P.E., C.F.M. Department of Engineering Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky Abstract: Most of the flooding problems in Bowling Green, Kentucky are associated with sinkholes. Flood elevations for four sinkholes were determined using standard methods approved by FEMA. However, calculated flood elevations for two of these sinkholes were much lower than those commonly observed. One possible source of the error was found to be spill-over from uphill sinkholes. Using ArcGIS and 3D Analyst, watersheds were delineated and volumes held by sinkholes up to the lowest spill point were determined. This analysis showed that no significant correlation exists between area draining directly to the sinkholes and volume held. Also, most of the sinkholes studied have spill-over during the 100-yr flood. By accounting for spill-over, the watershed of one sinkhole grew from 11 hectares to more than 520 hectares. A calibrated model that accounted for both storage and spill-over of upstream sinkholes gave good agreement with observations of a 1998 flood. Introduction: Bowling Green in Warren County, Kentucky sits in one of the best-known karst (cave and limestone) areas in the world. Most storm water runoff drains into subterranean passages, and many flood problems are associated with sinkholes. Constructing stormwater drainage systems for this area is much more complicated than in non-karst and even some karst areas. In a non-karst area, most storm water from development is routed into surface streams. In Bowling Green, it is usually routed either into cave entrances or into storm water drainage wells. -

Batman", Production Draft, Revised by Warren Skaaren Rev

"Batman", production draft, revised by Warren Skaaren Rev. 10/10/88 (Pink) Rev. 10/12/88 (Blue) "BATMAN" Screenplay by Sam Hamm and Warren Skaaren Based on the Character Created by Bob Kane FIFTH DRAFT October 6, 1988 FADE IN: EXT. CITYSCAPE - NIGHT Gotham City. The City of Tomorrow: stark angles, creeping shadows, dense, crowded, as if hell had erupted through the sidewalks. A dangling fat moon shines overhead. EXT. GOTHAM SQUARE - NIGHT PUSHERS wave to HOOKERS. STREET HUSTLERS slap high-fives with three-card monte dealers. They all seem to know each other... with one conspicuous exception: A TOURIST FAMILY, MOM, DAD, AND LITTLE JIMMY, march warily down the main drag. Just out of a show. But the respectable theatre crowd has thinned out, and now -- Playbills in hand -- they're on Gotham's meanest street. MOM For God's sake, Harold, can we please just get a taxi?? DAD I'm trying to get a -- (shouting) TAXI!! Three cabs streak pass and disappear. Jimmy reads map. JIMMY We're going the wrong way. Nearby, STREET TYPES are beginning to snicker. DAD Put that AWAY. We'll look like tourists. TWO COPS lean on their patrol car outside an all-night souvlaki stand, sipping coffee and chatting with a HOOKER. The HOOKER smiles at Jimmy. Jimmy smiles back. Mom yanks him off down the street and glowers at Dad. DAD We'll never get a cab. Let's cut over to Seventh. JIMMY Seventh is that way. DAD I know where we are! EXT. SIDE STREET - NIGHT (THAT MOMENT) Deserted street lined with stripped-down cars. -

Lithologic Controls on Karst Groundwater Flow, Lost River Groundwater Basin, Warren County, Kentucky Christopher Groves Western Kentucky University

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 1-1987 Lithologic Controls on Karst Groundwater Flow, Lost River Groundwater Basin, Warren County, Kentucky Christopher Groves Western Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the Geology Commons, Hydrology Commons, Sedimentology Commons, and the Stratigraphy Commons Recommended Citation Groves, Christopher, "Lithologic Controls on Karst Groundwater Flow, Lost River Groundwater Basin, Warren County, Kentucky" (1987). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 1554. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1554 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1.1 rJlOLOGI . CO'\TI!OI.S 0\ KAII'I (;)101 '\1)1\ \ 11.11 1'1.01\ . LO~T RI\'EH GHOl\I)\\ ,\TEII IIA . I~ . \\AI!III COl '\1" . I\E.\rlCI\' i'r >t>nled to Th. Farult) of th. I).part" ... nt of G.ograph) And t;eolug) \\e tprn l\ nluck) t nhN~il) 110", (iug Gret.'ll. n.t'llluck ) In Partial Fulfillment of tho II quire", nt for th I)e~r .. uf Mast r of ~cif>nr JatHI;,U). 19K7 AUTHORIZATION FOR USE O F THESIS Perrnis.ion is hereby 'J:7i ~ranted to the Werle .... Kentucq University Library to ~ make, or aUow to be ...ade photocopies, rnicrofiln'a or other copies of thh the.l. for approprlat. research or .cholarly purpose •• reserved to the author for the ...a]dnl of any copi •• of thi.