Diagnosis of Inherited Platelet Disorders on a Blood Smear

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring the Potential of the Platelet Membrane Proteome As a Source Of

Donovan et al. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy 2013, 5:32 http://alzres.com/content/5/3/32 RESEARCH Open Access Exploring the potential of the platelet membrane proteome as a source of peripheral biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease Laura E Donovan1†, Eric B Dammer2†, Duc M Duong3, John J Hanfelt4, Allan I Levey1, Nicholas T Seyfried1,3* and James J Lah1* Abstract Introduction: Peripheral biomarkers to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have not been established. Given parallels between neuron and platelet biology, we hypothesized platelet membrane-associated protein changes may differentiate patients clinically defined with probable AD from noncognitive impaired controls. Methods: Purified platelets, confirmed by flow cytometry were obtained from individuals before fractionation by ultracentrifugation. Following a comparison of individual membrane fractions by SDS-PAGE for general proteome uniformity, equal protein weight from the membrane fractions for five representative samples from AD and five samples from controls were pooled. AD and control protein pools were further divided into molecular weight regions by one-dimensional SDS-PAGE, prior to digestion in gel. Tryptic peptides were analyzed by reverse-phase liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Ionized peptide intensities were averaged for each identified protein in the two pools, thereby measuring relative protein abundance between the two membrane protein pools. Log2-transformed ratio (AD/control) of protein abundances fit a normal distribution, thereby permitting determination of significantly changed protein abundances in the AD pool. Results: We report a comparative analysis of the membrane-enriched platelet proteome between patients with mild to moderate AD and cognitively normal, healthy subjects. -

Immunoglobulin G Is a Platelet Alpha Granule-Secreted Protein

Immunoglobulin G is a platelet alpha granule-secreted protein. J N George, … , L K Knieriem, D F Bainton J Clin Invest. 1985;76(5):2020-2025. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI112203. Research Article It has been known for 27 yr that blood platelets contain IgG, yet its subcellular location and significance have never been clearly determined. In these studies, the location of IgG within human platelets was investigated by immunocytochemical techniques and by the response of platelet IgG to agents that cause platelet secretion. Using frozen thin-sections of platelets and an immunogold probe, IgG was located within the alpha-granules. Thrombin stimulation caused parallel secretion of platelet IgG and two known alpha-granule proteins, platelet factor 4 and beta-thromboglobulin, beginning at 0.02 U/ml and reaching 100% at 0.5 U/ml. Thrombin-induced secretion of all three proteins was inhibited by prostaglandin E1 and dibutyryl-cyclic AMP. Calcium ionophore A23187 also caused parallel secretion of all three proteins, whereas ADP caused virtually no secretion of any of the three. From these data and a review of the literature, we hypothesize that plasma IgG is taken up by megakaryocytes and delivered to the alpha-granules, where it is stored for later secretion by mature platelets. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/112203/pdf Rapid Publication Immunoglobulin G Is a Platelet Alpha Granule-secreted Protein James N. George, Sherry Saucerman, Shirley P. Levine, and Linda K. Knieriem Division ofHematology, Department ofMedicine, University of Texas Health Science Center, and Audie L. Murphy Veterans Hospital, San Antonio, Texas 78284 Dorothy F. -

MYH9-Related Platelet Disorders

Reprinted with permission from Thieme Medical Publishers (Semin Thromb Hemost 2009;35:189-203) Homepage at www.thieme.com MYH9-Related Platelet Disorders Karina Althaus, M.D.,1 and Andreas Greinacher, M.D.1 ABSTRACT Myosin heavy chain 9 (MYH9)-related platelet disorders belong to the group of inherited thrombocytopenias. The MYH9 gene encodes the nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA (NMMHC-IIA), a cytoskeletal contractile protein. Several mutations in the MYH9 gene lead to premature release of platelets from the bone marrow, macro- thrombocytopenia, and cytoplasmic inclusion bodies within leukocytes. Four overlapping syndromes, known as May-Hegglin anomaly, Epstein syndrome, Fechtner syndrome, and Sebastian platelet syndrome, describe different clinical manifestations of MYH9 gene mutations. Macrothrombocytopenia is present in all affected individuals, whereas only some develop additional clinical manifestations such as renal failure, hearing loss, and presenile cataracts. The bleeding tendency is usually moderate, with menorrhagia and easy bruising being most frequent. The biggest risk for the individual is inappropriate treatment due to misdiagnosis of chronic autoimmune thrombocytopenia. To date, 31 mutations of the MYH9 gene leading to macrothrombocytopenia have been identified, of which the upstream mutations up to amino acid 1400 are more likely associated with syndromic manifestations than the downstream mutations. This review provides a short history of MYH9-related disorders, summarizes the clinical and laboratory character- istics, describes a diagnostic algorithm, presents recent results of animal models, and discusses aspects of therapeutic management. KEYWORDS: MYH9 gene, nonmuscle myosin IIA, May-Hegglin anomaly, Epstein syndrome, Fechtner syndrome, Sebastian platelet syndrome, macrothrombocytopenia The correct diagnosis of hereditary chronic as isolated platelet count reductions or as part of thrombocytopenias is important for planning appropri- more complex clinical syndromes. -

Alterations in Platelet Alpha-Granule Secretion and Adhesion on Collagen Under Flow in Mice Lacking the Atypical Rho Gtpase Rhobtb3

cells Article Alterations in Platelet Alpha-Granule Secretion and Adhesion on Collagen under Flow in Mice Lacking the Atypical Rho GTPase RhoBTB3 Martin Berger 1,2, David R. J. Riley 1, Julia Lutz 1, Jawad S. Khalil 1, Ahmed Aburima 1, Khalid M. Naseem 3 and Francisco Rivero 1,* 1 Centre for Atherothrombosis and Metabolic Disease, Hull York Medical School, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Hull, HU6 7RX Hull, UK; [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (D.R.J.R.); [email protected] (J.L.); [email protected] (J.S.K.); [email protected] (A.A.) 2 Department of Internal Medicine 1, University Hospital, RWTH Aachen, 52074 Aachen, Germany 3 Leeds Institute for Cardiovascular and Metabolic Medicine, University of Leeds, LS2 9NL Leeds, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-1482-466433 Received: 8 January 2019; Accepted: 7 February 2019; Published: 11 February 2019 Abstract: Typical Rho GTPases, such as Rac1, Cdc42, and RhoA, act as molecular switches regulating various aspects of platelet cytoskeleton reorganization. The loss of these enzymes results in reduced platelet functionality. Atypical Rho GTPases of the RhoBTB subfamily are characterized by divergent domain architecture. One family member, RhoBTB3, is expressed in platelets, but its function is unclear. In the present study we examined the role of RhoBTB3 in platelet function using a knockout mouse model. We found the platelet count, size, numbers of both alpha and dense granules, and surface receptor profile in these mice were comparable to wild-type mice. -

Familial Multiple Coagulation Factor Deficiencies

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Familial Multiple Coagulation Factor Deficiencies (FMCFDs) in a Large Cohort of Patients—A Single-Center Experience in Genetic Diagnosis Barbara Preisler 1,†, Behnaz Pezeshkpoor 1,† , Atanas Banchev 2 , Ronald Fischer 3, Barbara Zieger 4, Ute Scholz 5, Heiko Rühl 1, Bettina Kemkes-Matthes 6, Ursula Schmitt 7, Antje Redlich 8 , Sule Unal 9 , Hans-Jürgen Laws 10, Martin Olivieri 11 , Johannes Oldenburg 1 and Anna Pavlova 1,* 1 Institute of Experimental Hematology and Transfusion Medicine, University Clinic Bonn, 53127 Bonn, Germany; [email protected] (B.P.); [email protected] (B.P.); [email protected] (H.R.); [email protected] (J.O.) 2 Department of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology, University Hospital “Tzaritza Giovanna—ISUL”, 1527 Sofia, Bulgaria; [email protected] 3 Hemophilia Care Center, SRH Kurpfalzkrankenhaus Heidelberg, 69123 Heidelberg, Germany; ronald.fi[email protected] 4 Department of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, University Medical Center–University of Freiburg, 79106 Freiburg, Germany; [email protected] 5 Center of Hemostasis, MVZ Labor Leipzig, 04289 Leipzig, Germany; [email protected] 6 Hemostasis Center, Justus Liebig University Giessen, 35392 Giessen, Germany; [email protected] 7 Center of Hemostasis Berlin, 10789 Berlin-Schöneberg, Germany; [email protected] 8 Pediatric Oncology Department, Otto von Guericke University Children’s Hospital Magdeburg, 39120 Magdeburg, Germany; [email protected] 9 Division of Pediatric Hematology Ankara, Hacettepe University, 06100 Ankara, Turkey; Citation: Preisler, B.; Pezeshkpoor, [email protected] B.; Banchev, A.; Fischer, R.; Zieger, B.; 10 Department of Pediatric Oncology, Hematology and Clinical Immunology, University of Duesseldorf, Scholz, U.; Rühl, H.; Kemkes-Matthes, 40225 Duesseldorf, Germany; [email protected] B.; Schmitt, U.; Redlich, A.; et al. -

Adhesion Molecules and Relationship to Leukocyte Levels in Allergic Eye Disease

Adhesion Molecules and Relationship to Leukocyte Levels in Allergic Eye Disease Annette S. Bacon,1'5 James I. McGill,5 David F. Anderson,13 Susan Baddeley,1 Susan L Lightman,2 and Stephen T. Holgate1 PURPOSE. TO evaluate the conjunctival expression of leukocyte cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) and their relationship to leukocyte patterns on the microvasculature in the different clinical subtypes of allergic eye disease. METHODS. Immunohistochemical analysis, using appropriate monoclonal antibodies, was applied to glycolmethacrylate-embedded biopsies of bulbar and tarsal conjunctival tissue. The proportion of total blood vessels expressing a particular CAM was derived and related to individual cell types identified by cell-specific markers, such as mast cells, eosinophils, neutrophils, T cells, and macrophages. Statistical analysis was used to correlate adhesion molecule expression and, ulti- mately, cell type. RESULTS. There was a basal expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) (21% bulbar, 18% tarsal), E-selectin (15% bulbar, 21% tarsal), and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) (13% bulbar and tarsal) in normal controls. In seasonal and perennial (bulbar and tarsal conjunc- tival) allergic tissue, ICAM-1 and E-selectin were expressed in 40% to 78% of vessels; in chronic disease, they were expressed in 45% to 80% of vessels; and in vernal giant papillae, they were expressed in as many as 90% of vessels. There was also increased expression of endothelial VCAM-1 in all forms of allergic eye disease; the greatest values were found in vernal giant papillae (64%). Biopsies taken in winter from seasonal sufferers demonstrated a marked reduction in levels of all three CAMs compared with those taken in the pollen season. -

Intracerebral Bleeding in Young Infants Due to Rare Etiologies–A

eona f N tal l o B a io n l r o u g y o J Tewari et al., J Neonatal Biol 2016, 5:2 Journal of Neonatal Biology DOI: 10.4172/2167-0897.1000221 ISSN: 2167-0897 Case Report Open access Intracerebral Bleeding in Young Infants due to Rare Etiologies–A Report of two Cases Vishal Vishnu Tewari1*, Kunal Tewari2 and Ritu Mehta3 1Department of Pediatrics, Army Hospital (Referral and Research), New Delhi, India 2Department of Anaesthesia, Classified Specialist Anesthesia, Base Hospital, New Delhi, India 3Department of Pathology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India *Corresponding author: Vishal Vishnu Tewari, Department of Pediatrics, Army Hospital, New Delhi, India,Tel: +91-8826118889, E-mail: [email protected] Rec date: April 29, 2016; Acc date: May 16, 2016; Pub date: May 23, 2016 Copyright: © 2016 Tewari VV, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Neonates and young infants are physiologically encumbered by an inadequate hemostatic mechanism. They may also have inherited or acquired bleeding disorders which may have a catastrophic presentation with intracerebral hemorrhage. The need to reach an accurate diagnosis is paramount in order to provide accurate therapy and genetic counseling. We report two infants who presented with unprovoked life threatening massive intracerebral hemorrhage. The first infant was diagnosed and managed for congenital factor V deficiency while the second infant had Glanzmann thrombasthenia. Keywords: Intracerebral bleeding; Congenital factor V deficiency; disorder in the family. -

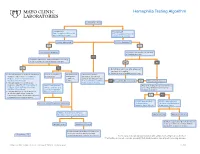

Hemophilia Testing Algorithm

Hemophilia Testing Algorithm Symptomatic male Hemophilia A Hemophilia B F8A / Coagulation Factor VIII F_9 / Coagulation Factor IX Activity Assay, Plasma Activity Assay, Plasma Activity decreased? Activity decreased? YES YES Hemophilia A diagnosis ■ Vitamin K antagonist (ie, warfarin) ■ Child/adolescent? NO F8 genetic testing has been performed on a family member and the specific mutation is known? YES NO YES NO ■ Retest when >4 weeks after antagonist treatment is complete ■ Adjust decreased activity levels for age ■ If known mutation is an Intron 1 Inversion Severe hemophilia: Moderate/mild If the activity assays mutation, order F81B / Hemophilia A activity <1% hemophilia: are normal, consider an F8 Gene, Intron 1 Inversion Known activity 1% alternate bleeding disorder: Mutation, Whole Blood* to 55% ALBLD / Bleeding Diathesis NO Is activity still decreased? YES Hemophilia B diagnosis ■ If known mutation is an Intron 22 Profile, Limited, Plasma inversion, order F822B / Hemophilia A F8INV / Hemophilia A F9 genetic testing has been performed F8 Gene, Intron 22 Inversion Known F8 Gene, Intron 1 and on a family member and the specific Mutation, Whole Blood* 22 Inversion Mutation mutation is known? ■ If known mutation is a point mutation Analysis, Whole Blood or deletion/duplication, contact a Laboratory Genetic Counselor to discuss YES NO targeted familial mutation testing FIXKM / Hemophilia B, NGSF9 / Hemophilia B, Inversion found Inversion not found F9 Gene Known F9 Gene, Next-Generation Mutation, Whole Blood* Sequencing, Varies F8NGS / -

Gri Trombosit Sendromu

Cukurova Medical Journal Cukurova Med J 2017;42(2):360-362 ÇUKUROVA ÜNİVERSİTESİ TIP FAKÜLTESİ DERGİSİ DOI: 10.17826/cutf.322967 OLGU SUNUMU / CASE REPORT Gray platelet syndrome Gri trombosit sendromu Fatima Ayaz1, Saeed Bin Ayaz2, Sunila Tashfeen2, Muhammad Furrukh1 1Benazir Bhutto Hospital, Rawalpindi, Punjab, Pakistan 2Combined Military Hospital, Okara, Punjab, Pakistan Cukurova Medical Journal 2017;42(2):360-362 Abstract Öz Gray platelet syndrome (GPS) is an autosomal recessive Gri trombosit (platelet) sendromu (GPS), trombositopeni disorder characterized by thrombocytopenia and defective ve ışık mikroskopunda soluk görünen kusurlu platelets that appear pale on light microscope. Patients trombositlerle karakterize, otozomal resesif geçişli bir present with easy bruisability, nose bleeds, menorrhagia hastalıktır. Hastalarda kolay morarma, burun kanaması, and prolonged bleeding. There is no specific treatment for menoraji ve uzun kanamalar görülmektedir. GPS için GPS and the management includes anticipating risks and spesifik bir tedavi bulunmamaktadır dolayısı ile hastalığa preventing bleeding by avoiding drugs that impair platelet karşı, riskleri öngörmek ve kanamanın önlenmesi function. We present here report of a case who presented için trombosit fonksiyonunu bozan ilaçlardan kaçınmak with repeated episodes of abnormal bleeding and was gerekmektedir. Bu olgu sunumunda, tekrarlayan anormal found to have GPS. kanama atakları olan ve GPS bulgusu bulunan bir vaka sunulmaktadır. Key words: Bleeding disorder, gray platelet syndrome, Anahtar -

Approach to Bleeding Diathesi

Approach to Bleeding Diathesis Dr.Nalini K Pati MD, DNB, DCH (Syd), FRCPA Paediatric Haematologist Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne Australia Objectives Objectives - I I. Clinical aspects of bleeding Clinical aspects of bleeding II. Hematologic disorders causing bleeding • Coagulation factor disorders • Platelet disorders III. Approach to acquired bleeding disorders • Hemostasis in liver disease • Surgical patients • Warfarin toxicity IV. Approach to laboratory abnormalities • Diagnosis and management of thrombocytopenia V. Drugs and blood products used for bleeding Clinical Features of Bleeding Disorders Petechiae Platelet Coagulation (typical of platelet disorders) disorders factor disorders Site of bleeding Skin Deep in soft tissues Mucous membranes (joints, muscles) (epistaxis, gum, vaginal, GI tract) Petechiae Yes No Ecchymoses (“bruises”) Small, superficial Large, deep Hemarthrosis / muscle bleeding Extremely rare Common Do not blanch with pressure Bleeding after cuts & scratches Yes No (cf. angiomas) Bleeding after surgery or trauma Immediate, Delayed (1-2 days), usually mild often severe Not palpable (cf. vasculitis) Ecchymoses (typical of coagulation factor disorders) Objectives - II Hematologic disorders causing bleeding – Coagulation factor disorders – Platelet disorders Coagulation factor disorders Hemophilia A and B Inherited bleeding Acquired bleeding Hemophilia A Hemophilia B disorders disorders Coagulation factor deficiency Factor VIII Factor IX – Hemophilia A and B – Liver disease – vonWillebrands disease – Vitamin K Inheritance X-linked X-linked recessive recessive – Other factor deficiencies deficiency/warfarin overdose Incidence 1/10,000 males 1/50,000 males –DIC Severity Related to factor level <1% - Severe - spontaneous bleeding 1-5% - Moderate - bleeding with mild injury 5-25% - Mild - bleeding with surgery or trauma Complications Soft tissue bleeding Hemarthrosis (acute) Hemophilia Clinical manifestations (hemophilia A & B are indistinguishable) Hemarthrosis (most common) Fixed joints Soft tissue hematomas (e. -

TPA-2012-2ING:Layout 1

106 Original Article DOI: 10.4274/tpa.823 Glanzmann thrombasthenia: Cerrahpaşa Medical Faculty experience Büşra Kutlubay, Gül Nihal Özdemir, Gülen Tüysüz, Hilmi Apak, Tiraje Celkan İstanbul University Cerrahpaşa Medical Faculty, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Hematology-Oncology, İstanbul, Turkey Sum mary Aim: Glazmann thrombasthenia is a rare autosomal recessive disease characterized by a defect in platelet aggregation. Herein, we report the management of children with Glazmann thrombasthenia followed up at Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty Pediatric Hematology Department. Material and Method: The files of nineteen patients (42% girls, 58% boys; median age: 10 months) were retrospectively reviewed. Results: The median age of onset of bleeding symptoms was 9 months (2 weeks-24 months). All patients presented with easy bruising and mucosal bleeding. Fourteen patients’ parents were consanguineous. In 15 patients, flow cytometry was performed. According to this, 7 patients had type I, 6 patients had type II and 2 patients had type III disease. Nine patients were treated with thrombocyte transfusion, tranexamic acid, recombinant active factor VII and fibrin glue as a single or combined therapy; none of them had a major bleeding complication. Conclusions: Bleeding control during invasive procedures may be challenging in children with Glazmann thrombasthenia; local treatments, DDAVP, steroid and antifibrinolytics may be used with success. (Turk Arch Ped 2012; 47: 106-8) Key words: Glanzmann thrombasthenia, thrombocyte function disorder Introduction test, GT platelets do not aggregate following interaction with any substance except for ristocetin. In addition to Glanzmann thrombasthenia (GT) was described by Dr. aggregometer, low than normal levels of glycoprotein (GP) IIb- Eduard Glanzmann in 1918 for the first time as abnormal clot IIIa can be determined with flow cytometer using CD41 and retraction and defects in platelets (1). -

Platelet Function Disorders

TREATMENT OF HEMOPHILIA APRIL 2008 • NO 19 PLATELET FUNCTION DISORDERS Second Edition Anjali A. Sharathkumar Amy Shapiro Indiana Hemophilia and Thrombosis Center Indianapolis, U.S.A. Published by the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH), 1999; revised 2008. © World Federation of Hemophilia, 2008 The WFH encourages redistribution of its publications for educational purposes by not-for-profit hemophilia organizations. In order to obtain permission to reprint, redistribute, or translate this publication, please contact the Communications Department at the address below. This publication is accessible from the World Federation of Hemophilia’s website at www.wfh.org. Additional copies are also available from the WFH at: World Federation of Hemophilia 1425 René Lévesque Boulevard West, Suite 1010 Montréal, Québec H3G 1T7 CANADA Tel. : (514) 875-7944 Fax : (514) 875-8916 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.wfh.org The Treatment of Hemophilia series is intended to provide general information on the treatment and management of hemophilia. The World Federation of Hemophilia does not engage in the practice of medicine and under no circumstances recommends particular treatment for specific individuals. Dose schedules and other treatment regimes are continually revised and new side effects recognized. WFH makes no representation, express or implied, that drug doses or other treatment recommendations in this publication are correct. For these reasons it is strongly recommended that individuals seek the advice of a medical adviser and/or consult printed instructions provided by the pharmaceutical company before administering any of the drugs referred to in this monograph. Statements and opinions expressed here do not necessarily represent the opinions, policies, or recommendations of the World Federation of Hemophilia, its Executive Committee, or its staff.