36 Ona MHCC and OD Paper DLSU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dole Regional Office 6 List of Government Internship Program (Gip) Beneficiaries

DOLE REGIONAL OFFICE 6 DOLE-GIP_Form C LIST OF GOVERNMENT INTERNSHIP PROGRAM (GIP) BENEFICIARIES NAME NATURE OF DURATION OF CONTRACT REMARKS EDUCATIONAL DOCUMENTS OFFICE/PLACE OF No. (Last Name, First Name, MI) ADDRESS AGE GENDER WORK/ (e.g. Contract ATTAINMENT SUBMITTED WORK/ ASSIGNMENT START DATE END DATE ASSIGNMENT completed or preterminated) 1 ABACAJIN, RICA JEANNE STO. NIÑO NORTE, AREVALO, ILOILO CITY 20 FEMALE COLLEGE LEVEL COMPLETED BRGY. HALL CLERK ABASTILLAS, GRACE BRGY. 1, IGBARAS 29 FEMALE BACHELOR OF TRANSCRIPT OF Municipal Hall, Igbaras, Office and SCIENCE IN RECORD & Iloilo Computer ELEMENTARY CERTIFICATE OF Works / 3/21/2016 EDUCATION INDIGENCY Encoding and 2 filling 9/21/2016 3 ABELLON, DUSTINE RAY BRGY. LOPEZ JAENA, JARO, ILOILO CITY 25 MALE COLLEGE GRADUATE COMPLETED BRGY. HALL CLERK MAR 1,2016 Aug. 31, 2016 Application Forms, ABELLON, JENNY BALONSIT Gen. Luna, Barotac Viejo, Iloilo 24 F College Graduate Transcript, Bragy. LGU-Barotac Viejo BV District HospitalFEB. 1, 2016 Jul.31,2016 4 Clearance 5 Abenir, Mary Ann C. Botongon, Estancia, Iloilo 21 F Vocational Graduate Certificate LGU Estancia Clerical 3/21/2016 9/21/2016 Certificate of 6 Abenir, Mary Chris Lantangan, Carles 21 F College Graduate Indigency,Transcript Lantangan Elementary SchoolClerical 4/11/2016 10/11/2016 7 Abido, Eduardo Jr. P Lopez Jaena St., Pototan, Iloilo 26 M College Graduate Transcript of Records Mayor's Office Encoding 3/16/2016 9/16/2016 8 ABOGAR, RIDEN S. TANZA TIMAWA II 18 M HIGH SCHOOL GRAD. COMPLETED BRGY. HALL CLERK FEB. 15, 2016 AUG. 15, 206 Application Form, Form Absalon, Marry Brgy. Bayuyan, Estancia, Iloilo 25 F High School Graduate LIGA Office Clerical work 3/16/2016 9/16/2016 9 137 10 Acebuque, Karl Anthony P. -

Metro Iloilo Development Council: in Pursuit of Managed Urban Growth

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Cuenca, Janet S.; Villanueva-Ruiz, Eden C. Working Paper Metro Iloilo Development Council: In Pursuit of Managed Urban Growth PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 2004-52 Provided in Cooperation with: Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Philippines Suggested Citation: Cuenca, Janet S.; Villanueva-Ruiz, Eden C. (2004) : Metro Iloilo Development Council: In Pursuit of Managed Urban Growth, PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 2004-52, Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Makati City This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/127880 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Philippine Institute for Development Studies Surian sa mga Pag-aaral Pangkaunlaran ng Pilipinas Metro Iloilo Development Council: In Pursuit of Managed Urban Growth Eden C. -

Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 1

COST OF DOING BUSINESS IN THE PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2017 Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 1 2 Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 F O R E W O R D The COST OF DOING BUSINESS is Iloilo Provincial Government’s initiative that provides pertinent information to investors, researchers, and development planners on business opportunities and investment requirements of different trade and business sectors in the Province This material features rates of utilities, such as water, power and communication rates, minimum wage rates, government regulations and licenses, taxes on businesses, transportation and freight rates, directories of hotels or pension houses, and financial institutions. With this publication, we hope that investors and development planners as well as other interested individuals and groups will be able to come up with appropriate investment approaches and development strategies for their respective undertakings and as a whole for a sustainable economic growth of the Province of Iloilo. Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 3 4 Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword I. Business and Investment Opportunities 7 II. Requirements in Starting a Business 19 III. Business Taxes and Licenses 25 IV. Minimum Daily Wage Rates 45 V. Real Property 47 VI. Utilities 57 A. Power Rates 58 B. Water Rates 58 C. Communication 59 1. Communication Facilities 59 2. Land Line Rates 59 3. Cellular Phone Rates 60 4. Advertising Rates 61 5. Postal Rates 66 6. Letter/Cargo Forwarders Freight Rates 68 VII. -

2017 Iloilo 4Th DEO Package

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS REGIONAL OFFICE VI Fort San Pedro, Iloilo City, Iloilo TERMS OF REFERENCE Consulting Services for the Data Gathering, Surveys, and Investigation for the Feasibility Study of the Proposed Bypass Projects in Iloilo 4th DEO 1. Iloilo Circumferential Road 2 (C-2) 2. Iloilo Circumferential Road (C-3) 3. Zarraga-Sta. Barbara –Airport Road 4. Lapayon-Cabugao Norte-Sen. Benigno S. Aquino, Jr. Ave. 1.0 INTRODUCTION The Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) is seeking to develop its pipeline of road transport projects nationwide for implementation and/or possible external financial assistance in their implementation. As part of the initial stage in the project development cycle, feasibility studies assessing the technical, economic, environmental, and social impacts of the project are required. The proposed conduct of data gathering, surveys and investigation for the feasibility of these projects is envisaged to be carried out by local consultant to be outsourced by the Planning and Design Division, DPWH Regional Office VI with the assistance of the Project Preparation Division, Planning Service (PPD, PS). The output of the consulting service shall be used for the conduct of feasibility for the proposed Iloilo Circumferential Road 2 (C-2), Iloilo Circumferential Road 3 (C-3), Zarraga-Sta. Barbara-Airport Road and Lapayon-Cabugao Norte-Sen. Benigno S. Aquino, Jr. Ave. The feasibility study is expected to determine the extent and nature of improvements/construction required, the economic and technical justifications thereof and in relation to their environmental and social impacts, and the development of a suitable and optimal investment program. -

Iloilo Provincial Profile 2012

PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2012 Annual Provincial Profile TIUY Research and Statistics Section i Provincial Planning and Development Office PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2012 Annual Provincial Profile P R E F A C E The Annual Iloilo Provincial Profile is one of the endeavors of the Provincial Planning and Development Office. This publication provides a description of the geography, the population, and economy of the province and is designed to principally provide basic reference material as a backdrop for assessing future developments and is specifically intended to guide and provide data/information to development planners, policy makers, researchers, private individuals as well as potential investors. This publication is a compendium of secondary socio-economic indicators yearly collected and gathered from various National Government Agencies, Iloilo Provincial Government Offices and other private institutions. Emphasis is also given on providing data from a standard set of indicators which has been publish on past profiles. This is to ensure compatibility in the comparison and analysis of information found therewith. The data references contained herewith are in the form of tables, charts, graphs and maps based on the latest data gathered from different agencies. For more information, please contact the Research and Statistics Section, Provincial Planning & Development Office of the Province of Iloilo at 3rd Floor, Iloilo Provincial Capitol, and Iloilo City with telephone nos. (033) 335-1884 to 85, (033) 509-5091, (Fax) 335-8008 or e-mail us at [email protected] or [email protected]. You can also visit our website at www.iloilo.gov.ph. Research and Statistics Section ii Provincial Planning and Development Office PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2012 Annual Provincial Profile Republic of the Philippines Province of Iloilo Message of the Governor am proud to say that reform and change has become a reality in the Iloilo Provincial Government. -

REGION 6 Address: Quintin Salas, Jaro, Iloilo City Office Number: (033) 329-6307 Email: [email protected] Regional Director: Dianne A

REGION 6 Address: Quintin Salas, Jaro, Iloilo City Office Number: (033) 329-6307 Email: [email protected] Regional Director: Dianne A. Silva Mobile Number: 0917 311 5085 Asst. Regional Director: Lolita V. Paz Mobile Number: 0917 179 9234 Provincial Office : Aklan Provincial Office Address : Linabuan sur, Banga, Aklan Office Number : (036) 267 6614 Email Address : [email protected] Provincial Manager : Benilda T. Fidel Mobile Number : 0915 295 7665 Buying Station : Aklan Grains Center Location : Linabuan Sur, Banga, Aklan Warehouse Supervisor : Ruben Gerard T. Tubao Mobile Number : 0929 816 4564 Service Areas : Municipalities of New Washington, Banga, Malinao, Makato, Lezo, Kalibo Buying Station : Oliveros Warehouse Location : Makato, Aklan Warehouse Supervisor : Iris Gail S. Lauz Mobile Number : 0906 042 8833 Service Areas : Municipalities of Makato and Lezo Buying Station : Magdael Warehouse Location : Lezo, Aklan Warehouse Supervisor : Ruben Gerard T. Tubao Mobile Number : 0929 816 4564 Service Areas : Municipalities of Malinao and Lezo Buying Station : Ibajay Buying Station Location : Ibajay, Aklan Warehouse Supervisor : Iris Gail S. Laus Mobile Number : 0906 042 8833 Service Areas : Municipality of Ibajay Buying Station : Mobile Procurement Team - 5 Location : Team Leader : Cristine B. Penuela Mobile Number : 0929 530 3103 Service Areas : Municipalities of Malinao and Ibajay Provincial Office : Antique Provincial Office Address : San Fernando, San Jose, antique Office Number : (036) 540-3697 / 0927 255 8191 Email Address : [email protected] Provincial Manager : Ma. Theresa O. Alarcon Mobile Number : 0917 596 1732 Buying Station : GID Camp Fullon Location : San Fernando, San Jose, Antique Warehouse Supervisor : Judy F. Devera Mobile Number : 0916 719 8151 Service Areas : Municipalities in Cental and Southern Antique Buying Station : GID Culasi Location : Caridad, Culasi Warehouse Supervisor : Ma. -

Os Media07sep

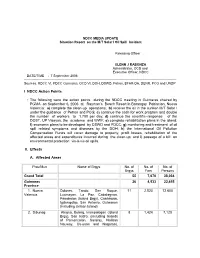

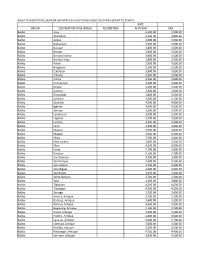

NDCC MEDIA UPDATE Situation Report on the M/T Solar I Oil Spill Incident Releasing Officer GLENN J RABONZA Administrator, OCD and Executive Officer, NDCC DATE/TIME : 7 September 2006 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Sources: RDCC VI, PDCC Guimaras, OCD VI, DOH, DSWD, Petron, BFAR-DA, DENR, PCG and UNDP I NDCC Action Points • The following were the action points during the NDCC meeting in Guimaras chaired by PGMA on September 6, 2006 at Rayman’s Beach Resort in Barangay Poblacion, Nueva Valencia: a) complete the clean-up operations; b) recover the oil in the sunken M/T Solar I under the guidance of Petron and PCG; c) continue the cash for work program and double the number of workers to 1,700 per day; d) continue the scientific–response of the DOST, UP Visayas, the academe and WWF; e) complete rehabilitation plans in the island; f) economic plans to be developed by DSWD and PDCC; g) monitoring and treatment of oil spill related symptoms and diseases by the DOH; h) the International Oil Pollution Compensation Funds will cover damage to property, profit losses, rehabilitation of the affected areas and expenditures incurred during the clean-up; and i) passage of a bill on environmental protection vis-à-vis oil spills. II. Effects A. Affected Areas Prov/Mun Name of Brgys No. of No. of No. of Brgys Fam Persons Grand Total 55 7,676 38,034 Guimaras 26 4,533 22,655 Province 1. Nueva Dolores, Tando, San Roque, 11 2,520 12,600 Valencia Lucmayan, La Paz, Cabalagnan, Panobolon (Island Brgy), Canhawan, Igdarapdap, San Antonio, Guiwanon (including Unisan Island) 2. -

Foreclosurephilippines.Comauction)

Acquired Asset Management Group 7th Flr. JELP Business Solutions Center Shaw Boulevard Mandaluyong City INVITATION TO BID April 26, 2018 The Pag-IBIG Fund Committee on Disposition of Acquired Assets shall conduct a public auction for the sale of acquired asset properties at on: DATE VENUE AREAS NO. OF UNITS May 18, 2018 Regatta Hotel, Gen. Luna Street, Iloilo Iloilo City, Iloilo Province, 45 City Capiz TOTAL 45 GENERAL GUIDELINES 1. Interested parties are required to secure copies of: (a) INSTRUCTION TO BIDDERS (HQP-AAF-104) and (b) OFFER TO BID (HQP-AAF-103) from the Technical Working Group (TWG) on the venue or may download the forms at www.pagibigfund.gov.ph (link Disposition of Acquired Assets for Public Auction). 2. Properties shall be sold on an “AS IS, WHERE IS” basis. 3. All interested buyers are encouraged to inspect the property/ies before tendering their offer/s. The list of the properties may be viewed at www.pagibigfund.gov.ph/aa/aa.aspx (Other properties for sale-Disposition of Acquired Assets for Public ForeclosurePhilippines.comAuction). 4. Bidders are also encouraged to visit our website, www.pagibigfund.gov.ph/aa/aa.aspx five (5) days prior the actual auction date, to check whether there are any erratum posted on the list of properties posted under the sealed public auction. 5. Sealed proposals shall be received by the Committee on Disposition of Acquired Assets’ Secretariat at the designated venue, starting 9:00 AM but not later than 12:00 NN or upon declaration of the closing of bid acceptance by the Committee on the scheduled date; the said proposals shall be opened immediately in the presence of the committee and attending bidders. -

Last Name) (First Name)

DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT Regional Office No. VI Special Program for Employment of Students (SPES) List of SPES Beneficiaries CY 2018 As of DECEMBER 31, 2019 ACCOMPLISH IN CAPITAL LETTERS Name of Student No. Province Employer Address (Last Name) (First Name) 1 AKLAN LGU BALETE ARANAS CYREL KATE ARANAS, BALETE, AKLAN 2 AKLAN LGU BALETE DE JUAN MA. JOSELLE MAY MORALES, BALETE, AKLAN 3 AKLAN LGU BALETE DELA CRUZ ELIZA CORTES, BALETE, AKLAN 4 AKLAN LGU BALETE GUIBAY RESIA LYCA CALIZO, BALETE, AKLAN 5 AKLAN LGU BALETE MARAVILLA CHRISHA SEPH ALLANA POBLACION, BALETE, AKLAN 6 AKLAN LGU BALETE NAGUITA QUENNIE ANN ARCANGEL, BALETE, AKLAN 7 AKLAN LGU BALETE NERVAL ADE FULGENCIO, BALETE, AKLAN 8 AKLAN LGU BALETE QUIRINO PAULO BIANCO ARANAS, BALETE, AKLAN 9 AKLAN LGU BALETE REVESENCIO CJ POBLACION, BALETE, AKLAN 10 AKLAN LGU BALETE SAUZA LAIZEL ANNE GUANKO, BALETE, AKLAN 11 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE AMBAY MA. JESSA CARMEN, PANDAN, ANTIQUE 12 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE ARCEÑO SHAMARIE LYLE ANDAGAO, KALIBO, AKLAN 13 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE BAUTISTA CATHERINE MAY BACHAO SUR, KALIBO, AKLAN 14 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE BELINARIO JESSY ANNE LOUISE TAGAS, TANGALAN, AKLAN 15 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE BRACAMONTE REMY CAMALIGAN, BATAN, AKLAN 16 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE CONTRATA MA. CRISTINA ASLUM, IBAJAY, AKLAN 17 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE CORDOVA MARVIN ANDAGAO, KALIBO, AKLAN 18 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE DE JUAN CELESTE TAGAS, TANGALAN, AKLAN 19 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE DELA CRUZ RALPH VINCENT BUBOG, NUMANCIA, AKLAN 20 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE DELIMA BLESSIE JOY POBLACION, LIBACAO, AKLAN 21 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE DESALES MA. -

MA530 Provincereferenceserie

MA530_A1_v02_Iloilo ! MA LAY ! Nabas ! B A L U D B U R U A N G A! Nabas N A B A S LI B E R TA D IBA J AY ! 0 Tangalan 0 Ibajay ! 0 ! 0 0 3 1 PAN D A N ! Tangalan ! Numancia Masbate MA K ATO ! N U M A N C I A Masbate ! K A L IB O TA N G A L A N L E Z O ! ! Banga Roxas B A N G A N E W Malinao WA S H I N G TO N City 0 ! 0 Batan 0 M A L I N A O ! ⛳☁ 0 Aklan R O X A S 8 ! Carles 2 1 Aklan ! Balete C I T Y S E B A S T E B A L E T E ! BATAN Ivisan ! Panay C A R L E S ! Madalag ! PANAY ALTAVAS IV IS A N ! ! Pilar M A D A L A G ! Pontevedra ! S A P I- A N P I L A R ! Balasan ! ! L I B A C A O President B A L A S A N S I G M A PA NITAN ES TA N C IA Culasi M A M B U S A O Roxas ! Libacao ! ! Sigma ! Batad 0 ! P O N T E V E D R A ! 0 C U L A S I 0 J A M I N D A N 0 ! Jamindan Dao P R E S I D E N T BATAD 6 ! Maayon 2 ! 1 Capiz D A O R O X A S Capiz M A- AY O N S A N D I O N IS I O ! Cuartero S A R A T I B I A O D U M A L A G C U A R T E R O San ! Dumalag TAPAZ Dumarao ! Dionisio B A R B A Z A ! ! Sara D U M A R A O 0 0 Lemery 0 ! 0 ! Tapaz Concepcion 4 Bingawan ! 2 ! LE M E RY 1 BI NG AWA N San C O N C E P C IO N Ajuy PA S S I S A N ! Rafael A J U Y ! C A L IN O G C IT Y R A FA E L L A U A - A N B U G A S O N G S A N L A M B U N A O Lambunao ! Calinog Antique ! E N R I Q U E San B A R O TA C Barotac Enrique ! ! V IE J O ! Viejo 0 0 Bugasong D U E N A S 0 ! 0 Iloilo BA N AT E 2 VA L D E R R A M A 2 1 Valderrama D I N G L E ! JA N IU AY ! Badiangan ! ! Anilao ! Banate B A D I A N G A N Antique PO TO TA N A N I L A O Iloilo ! Janiuay ! ! ! Catapud ! Pototan ! S A N ! Mina Patnoñgon ! San R E M I G I O M A A S I N M I N A B A R O TA C M A N A P L A ! PAT N ON G O N Remigio A L I M O D IA N ! N U E V O E N R I Q U E B . -

Point to Point Pick Up/Drop Off Rates Kalibo to Any

POINT TO POINT PICK UP/DROP OFF RATES KALIBO TO ANY POINT OF PANAY (POINT TO POINT) RATE ORIGIN DESTINATION (VISE VERSA) KILOMETERS AUV/VAN CAR Kalibo Ajuy 4,200.00 3,900.00 Kalibo Alimodian 4,100.00 3,800.00 Kalibo Anilao 4,000.00 3,700.00 Kalibo Badiangan 3,900.00 3,600.00 Kalibo Balasan 3,800.00 3,500.00 Kalibo Banate 3,800.00 3,500.00 Kalibo Barotac Nuevo 3,900.00 3,600.00 Kalibo Barotac Viejo 3,800.00 3,500.00 Kalibo Batad 3,900.00 3,600.00 Kalibo Bingawan 3,100.00 2,900.00 Kalibo Cabatuan 3,900.00 3,600.00 Kalibo Calinog 3,200.00 3,000.00 Kalibo Carles 4,200.00 3,900.00 Kalibo Concepcion 4,200.00 3,900.00 Kalibo Dingle 3,400.00 3,100.00 Kalibo Duenas 3,300.00 3,000.00 Kalibo Dumangas 3,800.00 3,500.00 Kalibo Estancia 4,000.00 3,700.00 Kalibo Guimbal 4,300.00 4,000.00 Kalibo Igbaras 4,600.00 4,300.00 Kalibo Janiuay 3,600.00 3,300.00 Kalibo Lambunao 3,500.00 3,200.00 Kalibo Leganes 3,700.00 3,500.00 Kalibo Lemery 3,700.00 3,400.00 Kalibo Leon 4,300.00 4,000.00 Kalibo Maasin 3,900.00 3,600.00 Kalibo Miagao 4,600.00 4,300.00 Kalibo Mina 3,700.00 3,400.00 Kalibo New Lucena 3,800.00 3,500.00 Kalibo Oton 4,300.00 4,000.00 Kalibo Pavia 3,700.00 3,400.00 Kalibo Pototan 3,700.00 3,400.00 Kalibo San Dionisio 4,200.00 3,900.00 Kalibo San Enrique 3,400.00 3,100.00 Kalibo San Joaquin 4,700.00 4,400.00 Kalibo San Miguel 4,200.00 3,900.00 Kalibo San Rafael 3,500.00 3,200.00 Kalibo Santa Barbara 3,700.00 3,400.00 Kalibo Sara 4,100.00 3,800.00 Kalibo Tigbauan 4,300.00 4,000.00 Kalibo Tubungan 4,500.00 4,200.00 Kalibo Zarraga 3,700.00 3,400.00 Kalibo -

F I L I P I N a S F I L I P I N a S F I L I P I N a S F I L I P I N

○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ ○○○○○ ○○○○ N.º 0 - Año 2002 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ FILIPINASFILIPINAS1 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ ○○○ Navegando por los caminos de los «ZARRAGA» ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ FILIPINAS - ILO ILO The Visayas is composed of six major islands and scores of islets strewn across the area in between the two major islands of Luzon in the north and Mindanao down south. It is situated in the heart of the Philippines, with its islands forming channels and straits that funnel water flowing freely from the vast Pacific Ocean in the east towards the South China Sea. Iloilo, the "Jewel of the South" is located on the southeastern side of Panay Island. Surrounded by Capiz on the north, Guimaras Strait on the south, Panay Gulf and Iloilo Strait on the east and Antique on the west. The province was originally known as Irong-Irong meaning "nose like", and then the Spanish shortened it ○○○○○○○○ and became Iloilo. Iloilo's main economic industry is agriculture and is dubbed as the "Food Basket and Rice Granary of the 2 Philippines" for being one of the leading producers of rice and other crops like legumes and root crops and fruits like mangoes, pineapple and citrus. Fishing is also an important industry, with Panay Gulf and Iloilo Strait as major fishing grounds that produce grouper, sea bass, tuna, blue marlin, prawn, milkfish and shrimps. The cottage industry is Iloilo’s second source of income. The town of Jaro is known for their loom weaving and hand embroidery of piña and jusi, fabrics used for making Filipino costumes such as barong tagalog, shirts, shawls, table cloth and place mats. Shell crafts, bamboo craft and mosquito nets are also some of the province’s products.