Outpost Years for a Start-Up Agency: the Ftc from 1921–1925

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gandhi As Mahatma: Gorakhpur District, Eastern UP, 1921-2'

Gandhi as Mahatma 289 of time to lead or influence a political movement of the peasantry. Gandhi, the person, was in this particular locality for less than a day, but the 'Mahatma' as an 'idea' was thought out and reworked in Gandhi as Mahatma: popular imagination in subsequent months. Even in the eyes of some local Congressmen this 'deification'—'unofficial canonization' as the Gorakhpur District, Eastern UP, Pioneer put it—assumed dangerously distended proportions by April-May 1921. 1921-2' In following the career of the Mahatma in one limited area Over a short period, this essay seeks to place the relationship between Gandhi and the peasants in a perspective somewhat different from SHAHID AMIN the view usually taken of this grand subject. We are not concerned with analysing the attributes of his charisma but with how this 'Many miracles, were previous to this affair [the riot at Chauri registered in peasant consciousness. We are also constrained by our Chaura], sedulously circulated by the designing crowd, and firmly believed by the ignorant crowd, of the Non-co-operation world of primary documentation from looking at the image of Gandhi in this district'. Gorakhpur historically—at the ideas and beliefs about the Mahatma —M. B. Dixit, Committing Magistrate, that percolated into the region before his visit and the transformations, Chauri Chaura Trials. if any, that image underwent as a result of his visit. Most of the rumours about the Mahatma.'spratap (power/glory) were reported in the local press between February and May 1921. And as our sample I of fifty fairly elaborate 'stories' spans this rather brief period, we cannot fully indicate what happens to the 'deified' image after the Gandhi visited the district of Gorakhpur in eastern UP on 8 February rioting at Chauri Chaura in early 1922 and the subsequent withdrawal 1921, addressed a monster meeting variously estimated at between 1 of the Non-Co-operation movement. -

Survey of Current Business October 1924

MONTHLY SUPPLEMENT TO COMMERCE REPORTS UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE WASHINGTON SURVEY OF CURRENT BUSINESS OCTOBER, 1924 No. 38 COMPILED BY BUREAU OF THE CENSUS BUREAU OF FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC COMMERCE BUREAU OF STANDARDS IMPORTANT NOTICE In addition to figures given from Government sources9 there are also incorporated for completeness of service figures from other sources generally accepted by the trades, the authority and responsibility for which are noted in the "Sources of data9' at the end of this number Subscription price of the SURVEY OF CURRENT BUSINESS is* $1.50 a year; single copies (monthly), 10 cents, quarterly issues, 20 cents. Foreign subscriptions, $2.25; single copies (monthly issues) including postage, 14 cents, quarterly issues, 31 cents. Subscription price of COMMERCE REPORTS is $4 a year; with the Survey, $5.50 a year. Make remittances only to Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C, by postal money order, express order, or New York draft. Currency at sender's risk. Postage stamps or foreign money not accepted. ^v - WASHINQTON : GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE : 1994 INTRODUCTION The SURVEY OF CURRENT BUSINESS is designed to period has been chosen. In a few cases other base present each month a picture of the business situation periods are used for special reasons. In all cases the by setting forth the principal facts regarding the vari- base period is clearly indicated. ous lines of trade and industry. At quarterly intervals The relative numbers are computed by allowing the detailed tables are published giving, for each item, monthly average for the base year or period to equal monthly figures for the past two years and yearly com- 100. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

'Olony and Protectorate of Kenya

THE OFFICIAL GAZETTE OF THE ‘OLONY AND PROTECTORATE OF KENYA. Published under the Authority of His Excellency the Governor of the Colony and Protectorate of Kenya. (Vol. XXVI.—No. 952| NATROBI, June 1], 1924.. [Price 50 Cents| Registered as a Newspaper at the G. P. 0. | Published every Wednesday. TABLE OF CONTENT S. PAGE. (to vt, ” Notice No. 203—Arrivals, Departures and Appointments, etc. a 534 x 2 ” 204—A Bill Intituled An Ordinance to Amend the Divorce Ordinance, 1908 hae 539 Proclamation No, 100—The Customs Ordinance, 1910,Proclamation. 536 Govt. Notice No. 205— ,, » Do » ules 536 536 33 a7 33 206—The Liquor (Amendment) Ordinance, 1923,— Plateau Licensing Area 33 33 a2 207—Confirmation of Ordinances—XXIT and XXXVI of 1923 537 Proclamation No. 101—-The Diseases of Animals Ordinance, 1906 5387 102—The Diseases of Animals Ordinance, 1906 ” 33 3 537 103——-The Diseases of Ai imals Ordinance, 1906 3) 33 ” 537 ” ” 23 104—The Diseases of Animals Ordinance, 1906 538 Govt. Notice No. 208—The Liquor (Amendment) Ordinance, 19238Appointment of Members of Plateau Licensing Court . 538 33 a3 33 209-——The Commission of Inquiry Ordinance, 1912Appointment 538 oy 9 210—The Municipal Corporations Ordinance, 1922-—-Appointment 538 a 3} 3? 211—The Liquor (Amendment) Ordinance, 1923 539 539 af a) a) 212—-Executive Council_—Appoimtment 539 at a? 32 213—The Native Registration Ordinance, 1921—Appointment... 214— ” ” » 1921—Appoimtment 539 3} oe] 7 M2 ” 215—The Native Authority Ordinance, 1912,—Appointment 539 Gen. Notices Nos. 450-462—Miscellaneous Notices .. 009-042 534 THE OFFICIAL GAZETTE June 11, 1924, GOVERNMENT Notice No. -

The Foreign Service Journal, September 1924

AMERICAN Photo submitted by W. W. Schott THE TWELFTH CENTURY CATHEDRAL AT PALERMO Vol. VI SEPTEMBER. 1924 No. 9 FEDERAL-AMERICAN NATIONAL BANK NOW IN COURSE OF CONSTRUCTION IN WASHINGTON, D. C. W. T. GALLIHER, Chairman of the Board JOHN POOLE, President RESOURCES OVER $13,000,000.00 LLETIN JSlUn.; PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE AMERICAN CONSULAR ASSOCIATION VOL. VI. No. 9 WASHINGTON, D. C. SEPTEMBER, 1924 Speech By Mr. Grew THE day on which I took my first bath before I can assure you that the new Association will a Diplomatic or Consular officer and pro¬ receive the very warm and hearty support of the ceeded to my post (with apologies to the members of the diplomatic branch of the Service. last number of the BULLETIN) I experienced two I have always taken particular satisfaction in distinct feelings; one of pleasure and satisfaction the fact that my first post was a consular one and at entering this great service of ours and the other that I spent two years gaining familiarity with the of something bordering on consternation at the work of that branch of the Service. I shall never prospect of the ordeal of the bath. I find my¬ forget the youthful pride with which I first saw self today experiencing much the same feelings—- a report of mine on Egyptian cotton published in great pleasure and satisfaction in the enjoyment the Trade Bulletins: true, several nights of work of your very kind and courteous hospitality, which and many pages were boiled down to five or six I highly appreciate and for which I warmly thank lines of print, but I felt then that I had become you, and the other feeling of trepidation at the at least a modest member of the great army of prospect of trying to justify my presence here by experts who keep our country informed of com¬ telling you something of interest. -

Thirty-Second Annual List of Papers

1923.] LIST OF PUBLISHED PAPERS 485 THIRTY-SECOND ANNUAL LIST OF PAPERS READ BEFORE THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY AND SUBSEQUENTLY PUBLISHED, INCLUDING REFERENCES TO THE PLACES OF PUBLICATION ALEXANDER, J. W. A proof and extension of the Jordan-Brouwer separa tion theorem. Read April 29, 1916. Transactions of this Society, vol. 23, No. 4, pp. 333-349; June, 1922. Invariant points of a surface transformation of given class. Read Dec. 28, 1922. Transactions of this Society, vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 173- 184; April, 1923. BARNETT, I. A. Differential equations with a continuous infinitude of variables. Read Dec. 28, 1918. American Journal of Mathematics, vol. 44, No. 3, pp. 172-190; July, 1922. Linear partial differential equations with a continuous infinitude of variables. Read Dec. 28, 1918, and April 24, 1920. American Journal of Mathematics, vol. 45, No. 1, pp. 42-53; Jan., 1923. BELL, E. T. On restricted systems of higher indeterminate equations. Read (San Francisco) June 18, 1920. Transactions of this Society, vol. 22, No. 4, pp. 483-488; Oct., 1921. Anharmonic polynomial generalizations of the numbers of Bernoulli and Euler. Read (San Francisco) April 9, 1921. Transactions of this Society, vol. 24, No. 2, pp. 89-112; Sept., 1922. Periodicities in the theory of partitions. Read (San Francisco) April 8, 1922. Annals of Mathematics, (2), vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 1-22; Sept., 1922. Relations between the numbers of Bernoulli, Euler, Genocchi, and Lucas. Read (San Francisco) April 8, 1922. Messenger of Mathe matics, vol. 52, No. 4, pp. 56-64, and No. 5, pp. 65-68; Aug. -

Germany 1919-1941 U.S

U.S. MILITARY INTELLIGENCE REPORTS : GERMANY 1919-1941 U.S. MILITARY INTELLIGENCE REPORTS: GERMANY, 1919-1941 Edited by Dale Reynolds Guide Compiled by Robert Lester A Microfilm Project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA, INC. 44 North Market Street • Frederick, MD 21701 Copyright© 1983 by University Publications of America, Inc. All rights reserved. ISBN 0-89093^26-6. Note on Sources The Documents in this Collection are from the National Archives and Record Service, Washington, D.C., Record Group #165. Mil- itary Intelligence Division Files: Germany. TABLE OF CONTENTS Red Index 1 Reel I 1 Reel II 6 Reel III 10 Reel IV 15 Reel V 18 Reel VI 22 Reel VII 25 Reel VIII 29 Reel IX 31 Reel X 33 Reel XI 33 Reel XII 34 Reel XIII 35 Reel XIV 38 Reel XV 39 Reel XVI 41 Reel XVII 43 Reel XVIII 45 Reel XIX 47 Reel XX 49 Reel XXI 52 Reel XXII 54 Reel XXIII 56 Reel XXIV 58 Reel XXV 61 Reel XXVI 63 Reel XXVII 65 Reel XXVIII 68 Subject Index 71 Dates to Remember February 3,1917 Severance of U.S. Diplomatic Relations with Germany; Declara- tion of War November 11,1918 Armistice December 1, 1918 U.S. Troops of the 3rd Army cross the Rhine and Occupy the Rhine Province July 2,1919 Departure of the U.S. 3rd Army; the U.S. Army of the Rhine Occupies Coblenz in the Rhine Province December 10, 1921 Presentation of Credentials of the U.S. Charge d'Affaires in Berlin April 22, 1922 Withdrawal of U.S. -

British Security Policy in Ireland, 1920-1921: a Desperate Attempt by the Crown to Maintain Anglo-Irish Unity by Force

British Security Policy in Ireland, 1920-1921: A Desperate Attempt by the Crown to Maintain Anglo-Irish Unity by Force ‘What we are trying to do is to stop the campaign of assassination and arson, initiated and carried on by Sinn Fein, with as little disturbance as possible to people who are and who wish to be law abiding.’ General Sir Nevil Macready ‘outlining the British policy in Ireland’ to American newspaper correspondent, Carl W. Ackerman, on 2 April 1921.1 In the aftermath of victory in the Great War (1914-1918) and the conclusion to the peacemaking process at Versailles in 1919, the British Empire found itself in a situation of ‘imperial overstretch’, as indicated by the ever-increasing demands for Crown forces to represent and maintain British interests in defeated Germany, the Baltic and Black Seas regions, the Middle East, India and elsewhere around the world. The strongest and most persistent demand in this regard came from Ireland – officially an integral part of the United Kingdom itself since the Act of Union came into effect from 1 January 1801 – where the forces of militant Irish nationalism were proving difficult, if not impossible to control. Initially, Britain’s response was to allow the civil authorities in Ireland, based at Dublin Castle and heavily reliant on the enforcement powers of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), to deal with this situation. In 1920, however, with a demoralised administration in Ireland perceived to be lacking resolution in the increasingly violent struggle against the nationalists, London -

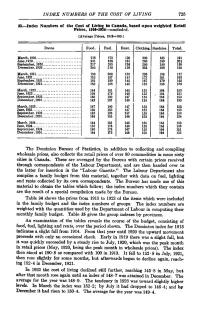

INDEX NUMBERS of the COST of LIVING 725 33.—Index Numbers of the Cost of Living in Canada, Based Upon Weighted Retail Prices

INDEX NUMBERS OF THE COST OF LIVING 725 33.—Index Numbers of the Cost of Living in Canada, based upon weighted Retail Prices, 1910-1934—concluded. (Average Prices, 1913=100.) Dates. Food. Fuel. Rent. Clothing. Sundries. Total. March, 1920 218 173 120 260 185 191 June,1920 231 186 133 260 190 201 September, 1920 217 285 136 260 190 199 December, 1920. 202 218 139 235 190 192 March, 1921 180 208 139 195 188 177 June,1921 152 197 143 173 181 163 September, 1921 161 189 145 167 170 162 December, 1921. 150 186 145 158 166 156 March, 1922 144 181 145 155 164 153 June, 1922 139 179 146 155 . 164 151 September, 1922. 140 190 147 155 164 153 December, 1922. 142 187 146 155 164 153 March, 1923 147 190 147 155 164 155 June,1923 139 182 147 155 164 152 September, 1923. 142 183 147 155 164 153 December, 1923. 146 185 146 155 164 154 March, 1924 144 181 146 155 164 153 June,1924 133 176 146 155 164 149 September, 1924. 140 176 147 155 164 151 December, 1924. 144 175 146 155 164 152 The Dominion Bureau of Statistics, in addition to collecting and compiling wholesale prices, also collects the retail prices of over 80 commodities in some sixty cities in Canada. These are averaged by the Bureau with certain prices received through correspondents of the Labour Department, and are then handed over to the latter for insertion in the "Labour Gazette." The Labour Department also compiles a family budget from this material, together with data on fuel, lighting and rents collected by its own correspondents. -

The Conservatives in British Government and the Search for a Social Policy 1918-1923

71-22,488 HOGAN, Neil William, 1936- THE CONSERVATIVES IN BRITISH GOVERNMENT AND THE SEARCH FOR A SOCIAL POLICY 1918-1923. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 History, modern University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE CONSERVATIVES IN BRITISH GOVERNMENT AND THE SEARCH FOR A SOCIAL POLICY 1918-1923 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Neil William Hogan, B.S.S., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 1971 Approved by I AdvAdviser iser Department of History PREFACE I would like to acknowledge my thanks to Mr. Geoffrey D.M. Block, M.B.E. and Mrs. Critch of the Conservative Research Centre for the use of Conservative Party material; A.J.P. Taylor of the Beaverbrook Library for his encouragement and helpful suggestions and his efficient and courteous librarian, Mr. Iago. In addition, I wish to thank the staffs of the British Museum, Public Record Office, West Sussex Record Office, and the University of Birmingham Library for their aid. To my adviser, Professor Phillip P. Poirier, a special acknowledgement#for his suggestions and criticisms were always useful and wise. I also want to thank my mother who helped in the typing and most of all my wife, Janet, who typed and proofread the paper and gave so much encouragement in the whole project. VITA July 27, 1936 . Bom, Cleveland, Ohio 1958 .......... B.S.S., John Carroll University Cleveland, Ohio 1959 - 1965 .... U. -

Palestine. Disturbances in May, 1921. Reports of the Commission Of

^sssaBomma^ma^am ^ f PALESTINE. DISTURBANCES IN MAY, 1921. Reports of the Commission of Inquiry WITH Correspondence Relating Thereto. Fresented to Parliament by Com7nand of His Majesty, October, 1921. LONDON: PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE. To be purchased through any Bookseller or directly from H.M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses: Imperial Housk, Kinosway, London, W.C. 2, and 23, Abingdon Street, London, S.W.I: 37, Peter Street, Manchester; 1, St, Andrew's Crescent, Cardiff; 2 <, Forth Street, Edinburgh ; or from BASON & SON, Ltd., 40 & 41, Lower Sackville Street, Dublin. 1921. Price One Shilling Net, [Cmd. 1540.] I N LIST OF PAPERSi PALESTINE. DISTURBANCES IN MAY, 1921. Reports of the Commission of Inquiry with Correspondence relating thereto. No. 1 TERMS OF REFERENCE. A. I APPOINT His Honour Sir Thomas Haycraft, Chief Justice of Palestine, Mr. H. C. Luke, Assistant Governor of Jerusalem, and Mr. Stubbs, of the Legal Department, to be a Commission to inquire into the recent disturbances in the town and neighbourhood of Jaffa, and to report thereon > And I appoint Sir Thomas Haycraft to be the Chairman, and Aref Pasha Dejani El Daoudi, Elias Eff. Mushabbeck and Dr. Eliash to be assessors to the Commission. The Commission shall have all the powers specified in Article 2 of the Commission of Inquiries Ordinance, 1921. HERBERT SAMUEL, High Commissioner for Palestine. 7th May, 1921. (B C-82) Wt. 17098-761 1500/90 11/21 H & S, Ltd. * B. I DIRECT the Commission of Inquiry, appointed by Order dated the 7th of May to inquire into and report upon the recent disturbances in the town and neighbourhood of Jaffa, to extend their inquiries and report further upon recent disturbances which have taken place in any part of the District of Jaffa or elsewhere in Palestine. -

Low-Latitude Auroras: the Magnetic Storm of 14–15 May 1921

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. Air Force Research U.S. Department of Defense 2001 Low-latitude auroras: the magnetic storm of 14–15 May 1921 S. M. Silverman E. W. Cliver Air Force Research Laboratory Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usafresearch Part of the Aerospace Engineering Commons Silverman, S. M. and Cliver, E. W., "Low-latitude auroras: the magnetic storm of 14–15 May 1921" (2001). U.S. Air Force Research. 4. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usafresearch/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Defense at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in U.S. Air Force Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics 63 (2001) 523–535 www.elsevier.nl/locate/jastp Low-latitude auroras: the magnetic storm of 14–15 May 1921 S.M. Silvermana; ∗, E.W. Cliver b a18 Ingleside Rd., Lexington, MA 02420, USA bSpace Vehicles Directorate, Air Force Research Laboratory, Hanscom AFB, MA 01731, USA Received 30 November 1999; accepted 28 January 2000 Abstract We review solar=geophysical data relating to the great magnetic storm of 14–15 May 1921, with emphasis on observations of the low-latitude visual aurora. From the reports we have gathered for this event, the lowest geomagnetic latitude of deÿnite overhead aurora (coronal form) was 40◦ and the lowest geomagnetic latitude from which auroras were observed on the poleward horizon in the northern hemisphere was 30◦.