France? Renaissance?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humanism and the Middle Way in the French Wars of Religion Thomas E

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 5-12-2017 Refuge, Resistance, and Rebellion: Humanism and the Middle Way in the French Wars of Religion Thomas E. Shumaker University of New Mexico, Albuquerque Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Shumaker, Thomas E.. "Refuge, Resistance, and Rebellion: Humanism and the Middle Way in the French Wars of Religion." (2017). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas Shumaker Candidate Graduate Unit (Department): History Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Charlie R. Steen, Chairperson Dr. Patricia Risso________________ Dr. Linda Biesele Hall____________ Dr. Marina Peters-Newell_________ i Refuge, Resistance, and Rebellion: Humanism and the Middle Way in the French Wars of Religion BY Thomas Shumaker B.A. magna cum laude, Ohio University, 1998 M.Div., Concordia Theological Seminary, 2004 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July, 2017 ii Refuge, Resistance, and Rebellion: Humanism and the Middle Way in the French Wars of Religion By Thomas Shumaker B.A. magna cum laude, Ohio University, 1998 M.Div. -

Joachim Du Bellay, Rome and Renaissance France

WRITING IN EXILE: JOACHIM DU BELLAY, ROME AND RENAISSANCE FRANCE G. HUGO TUCKER* INTRODUCTION: ANAMORPHOSIS—THE JOURNEY TO ROME La donq', Francoys, marchez couraigeusement vers cete superbe cité Romaine: & des serves dépouilles d'elle (comme vous avez fait plus d'une fois) ornez voz temples & autelz. (Du Bellay, Deffence, 'Conclusion') In his essay of 1872 on Joachim Du Bellay (c. 1523-60) the aesthetic critic, and Oxford Classics don Walter Pater wrote of the French Renaissance poet's journey to Rome and celebrated stay there (1553-57) in the service of his kinsman the Cardinal Jean Du Bellay: ... that journey to Italy, which he deplored as the greatest misfortune of his life, put him in full possession of his talent, and brought out all his originality.1 Pater's judgment here was at once both very right and very wrong. Wrong firstly, because Pater seems to have been thinking of Du Bellay more or less exclusively as the author of the Roman sonnet collection Les Regrets (January 1558), in order to ascribe to him, somewhat anachronistically, an originality derived directly from intense autobiographical experience and manifested artistically in an aesthetic of enhanced sincerity and spontaneity. No doubt he was encouraged, as the Parisian readership of 1558 might have been, by Du Bellay's ambiguous presentation of this elegiac and satirical sonnet sequence as a kind of disillusioned journal de voyage to Rome (and back) under the further guise of Ovidian exile. Yet this was also to underestimate the importance and diverse nature of Du Bellay's three other, generically very different, major Roman collections published in Paris on his return: in French, his Divers Jeux rustiques (January 1558) and grandiose Antiqui- tez de Rome .. -

I Letter on Humanism

i i I I I i v LETTER ON HUMANISM ~ To think is to confine yourself to a single thought that one day stands still like a star in the world's sky. Letter on Humanism 191 nature that would guarantee the rightness of his choice and the efficacy of his action. "There is reality only in action," Sartre in sists (p. 55), and existentialism "defines man by action" (p. 62), which is to say, "in connection with an engagement" (p. 78). Nevertheless, Sartre reaffirms (pp. 64 ff.) that man's freedom to act is rooted in subjectivity, which alone grants man his dignity, so that the Cartesian cogito becomes the only possible In Brussels during the spring of 1845, not long after his expul point de depart for existentialism and the only possible basis for sion from Paris, Karl Marx jotted down several notes on the a humanism (p. 93). German philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach. The second of these Heidegger responds by keeping open the question of action reads: "The question whether human thought achieves objective but strongly criticizing the tradition of subjectivity, which cele truth is not a question of theory but a practical question.... Dis brates the "I think" as the font of liberty. Much of the "Letter" pute over the actuality or nonactuality of any thinking that is taken up with renewed insistence that Dasein or existence is isolates itself from praxis is a purely scholastic question." Ever and remains beyond the pale of Cartesian subjectivism. Again since that time-especially in France, which Marx exalted as the Heidegger writes Existenz as Ek-sistenz in order to stress man's heart of the Revolution-the relation of philosophy to political "standing out" into the "truth of Being." Humanism underes practice has been a burning issue. -

The Loire and Its Castles: from the Roman Era to the Classic Age Levels: A1, A2, B1.1, B1.2, B2, C1 15 Contact Hours 1 U.S

The Loire and its Castles: From the Roman Era to the Classic Age Levels: A1, A2, B1.1, B1.2, B2, C1 15 Contact Hours 1 U.S. semester credit Overview: This series of lectures is about the multiplicity of castles, abbeys, and churches on a territory that is defined as French from Romanesque times to the Renaissance and the 17th century. In this context we will refer to some essential events of current times: exhibitions, birthdays, concerts… Course Contents: Some aspects of the castle concept in France, in the Loire Valley, from medieval fortresses to classical palaces (from the Romanesque period to the 17th century). Program by Session: 1. Build abbeys, churches, castles? History of a construction frenzy. Abbeys & Romanesque architecture, 10th-13th centuries, Fontevraud; castles before the Hundred Years War. And Parallel, introduction to the French Renaissance, the castle of Blois, unique example of styles, 4 centuries of architecture (Counts of Chatillon, 13th Century, Charles of Orleans, mid-15th century, Louis XII, 1498- 1505, Francois 1st, 1515-1524, Gaston of Orleans, 1635-1638) 2. History of a frenzy of construction, continued. From Romanesque to Gothic: why “gothic”? The work of Alienor d’Aquitaine in Poiters, a cathedral, a stained-glass window. A construction site in the Middle Ages… 3. Cathedrals at the tower of Babel? The Beginning of Gothic cathedrals… a. Birth of Gothic Art: 1140-1190. 2. Classical Gothic: 1190- 1240. The castles of the Gothic period (the hundred Years War, 1337-1453). Blois, continued. 4. The cathedral as a symbol; Reims, modern cathedral, “martyr cathedral”. From Gothic to Renaissance; preparation for the great projects of the Renaissance. -

Timothy Hampton

Hampton 1 Curriculum Vitae -- Timothy Hampton Coordinates Department of Comparative Literature, Department of French 4125 Dwinelle Hall #2580 University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720 (510) 642-2712 [email protected] Website: www.timothyhampton.org Employment 2017- Director, Doreen B. Townsend Center for the Humanities, UC Berkeley 1999-Present. Professor of French, and Comparative Literature (“below the line” appointment in Italian Studies), University of California, Berkeley 2014-ongoing. Holder of the Aldo Scaglione and Marie M. Burns Distinguished Professorship, UC Berkeley 2007-2011, Holder of the Bernie H. Williams Chair of Comparative Literature 1990-1999. Associate Professor of French, U.C. Berkeley 1986-1990. Assistant Professor of French, Yale University, New Haven, CT Visiting Positions 2019 (spring) Visiting Professor, University of Paris 8, Paris, France 2001 (spring) Comparative Literature, Stanford University 1994 (fall) French and Italian, Stanford University 1999 (summer) French Cultural Studies Institute, Dartmouth College Education Ph. D., Comparative Literature, Princeton University, 1987 M.A., Comparative Literature, University of Toronto, 1982 B.A., French and Spanish, University of New Mexico, summa cum laude, 1977 Languages Spanish, French, Italian, Latin, Portuguese, German, some Old Provençal, English Fellowships and Honors Fellow of the Institut d'Études Avancées, Paris (2014-15) Associate Researcher, Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, Paris, May-June 2015. Cox Family Distinguished Fellow in the Humanities, University of Colorado (2014) Campus Distinguished Teaching Award, UC Berkeley (2013) Hampton 2 Major Grant, Institute for International Education, UC Berkeley, "Diplomacy and Culture." 2012-13. Founding Research Network Member, Cambridge/Oxford University project on "Textual Ambassadors." 2012- (With Support from the Humanities Council of the UK). -

"The Philosophy of Humanism"

THE PHILOSOPHY OF HUMANISM Books by Corliss Lamont The Philosophy of Humanism, Eighth Edition, 1997 (posthumous) Lover’s Credo: Poems of Love, 1994 The Illusion of Immortality, Fifth Edition, 1990 Freedom of Choice Affirmed, Third Edition, 1990 Freedom Is as Freedom Does: Civil Liberties in America, Fourth Edition, 1990 Yes To Life: Memoirs of Corliss Lamont, 1990 Remembering John Masefield, 1990 A Lifetime of Dissent, 1988 A Humanist Funeral Service, 1977 Voice in the Wilderness: Collected Essays of Fifty Years, 1974 A Humanist Wedding Service, 1970 Soviet Civilization, Second Edition, 1955 The Independent Mind, 1951 The Peoples of the Soviet Union, 1946 You Might Like Socialism, 1939 Russia Day by Day Co-author (with Margaret I. Lamont), 1933 (Continued on last page of book) THE PHILOSOPHY OF HUMANISM CORLISS LAMONT EIGHTH EDITION, REVISED HALF-MOON FOUNDATION, INC. The Half-Moon Foundation was formed to promote enduring inter- national peace, support for the United Nations, the conservation of our country’s natural environment, and to safeguard and extend civil liberties as guaranteed under the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. AMHERST, NEW YORK 14226 To My Mother FLORENCE CORLISS LAMONT discerning companion in philosophy Published 1997 by Humanist Press A division of the American Humanist Association 7 Harwood Drive, P.O. Box 1188 Amherst, NY 14226-7188 Eighth Edition Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 96-77244 ISBN 0-931779-07-3 Copyright © 1949, 1957, 1965, 1982, 1990, 1992 by Corliss Lamont. Copyright © 1997 by Half-Moon Foundation, Inc. Copy Editor, Rick Szykowny ~ Page Layout, F. J. O’Neill The following special copyright information applies to this electronic text version of The Philosophy of Humanism, Eighth Edition: THIS DOCUMENT IS COPYRIGHT © 1997 BY HALF-MOON FOUNDATION, INC. -

RICHARD DAWKINS Ends All Debate

RICHARD DAWKINS Ends All Debate Celebrating Reason and Humanity WINTER 2002/03 • VOL. 23 No. 1 f Susan HAACK • Christopher HITCHENS Nat HENTOFF Peter SINGER Paul KURTZ • • Introductory Price $5.95 U.S. / $6.95 Can. 24> John Dewey and Sidney Hook Remembered 7725274 74957 Published by The Council for Secular Humanism THE AFFIRMATIONS OF HUMANISM: A STATEMENT OF PRINCIPLES* We are committed to the application of reason and science to the understanding of the universe and to the solving of human problems. We deplore efforts to denigrate human intelligence, to seek to explain the world in supernatural terms, and to look outside nature for salvation. We believe that scientific discovery and technology can contribute to the betterment of human life. We believe in an open and pluralistic society and that democracy is the best guarantee of protecting human rights from authoritarian elites and repressive majorities. We are committed to the principle of the separation of church and state. We cultivate the arts of negotiation and compromise as a means of resolving differences and achieving mutual understanding. We are concerned with securing justice and fairness in society and with eliminating discrimination and intolerance. We believe in supporting the disadvantaged and the handicapped so that they will be able to help themselves. We attempt to transcend divisive parochial loyalties based on race, religion, gender, nationality, creed, class, sexual orientation, or ethnicity, and strive to work together for the common good of humanity. We want to protect and enhance the earth, to preserve it for future generations, and to avoid inflicting needless suffering on other species. -

Review of Margaret Mcgowan, the Vision of Rome in Late Renaissance France

Bryn Mawr Review of Comparative Literature Volume 3 Article 3 Number 1 Fall 2001 Fall 2001 Review of Margaret McGowan, The iV sion of Rome in Late Renaissance France. Eric MacPhail Indiana University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmrcl Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Recommended Citation MacPhail, Eric (2001). Review of "Review of Margaret McGowan, The iV sion of Rome in Late Renaissance France.," Bryn Mawr Review of Comparative Literature: Vol. 3 : No. 1 Available at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmrcl/vol3/iss1/3 This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmrcl/vol3/iss1/3 For more information, please contact [email protected]. MacPhail: MacPhail on McGowan Margaret McGowan, The Vision of Rome in Late Renaissance France. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000. 461 pp. 101 black and white illustrations. 12 colored plates. ISBN 0300085354. Reviewed by Eric MacPhail , Indiana University Margaret McGowan's new book documents the transfer of ideas and images of Rome to France and the decisive impact which these visions had on French art and literature in the latter half of the sixteenth century. The first part of the work surveys the erudite and popular sources of the vision of Rome, while the second part analyzes the artistic response evoked by these sources. Throughout, more than a hundred illustrations embellish this patiently compiled and meticulously researched history of French Renaissance emulation of ancient Rome. The initial chapters on travel accounts and guide books reveal the complexity of a vision founded as much on memory and imagination as on objective experience. -

Humanism and Early Modern Philosophy Edited by Jill Kraye and M.W.F.Stone

London Studies in the History of Philosophy Series Editors: Jonathan Wolff, Tim Crane, M.W.F.Stone and Tom Pink London Studies in the History of Philosophy is a unique series of tightly focused edited collections. Bringing together the work of many scholars, some volumes will trace the history of the formulation and treatment of a particular problem of philosophy from the Ancient Greeks to the present day, while others will provide an in-depth analysis of a period or tradition of thought. The series is produced in collaboration with the Philosophy Programme of the University of London School of Advanced Study. 1 Humanism and Early Modern Philosophy Edited by Jill Kraye and M.W.F.Stone Forthcoming 2 Proper Ambition of Science Edited by M.W.F.Stone and Jonathan Wolff Humanism and Early Modern Philosophy Edited by Jill Kraye and M.W.F.Stone London and New York First published 2000 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. © 2000 Jill Kraye and M.W.F.Stone All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Humanism and early modern philosophy/[edited by] Jill Kraye and M.W.F.Stone. -

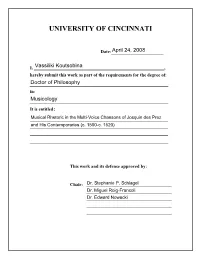

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Musical Rhetoric in the Multi-Voice Chansons of Josquin des Prez and His Contemporaries (c. 1500-c. 1520) A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Division of Composition, Musicology and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music By VASSILIKI KOUTSOBINA B.S., Chemistry University of Athens, Greece, April 1989 M.M., Music History and Literature The Hartt School, University of Hartford, Connecticut, May 1994 Committee Chair: Dr. Stephanie P. Schlagel 2008 ABSTRACT The first quarter of the sixteenth century witnessed tightening connections between rhetoric, poetry, and music. In theoretical writings, composers of this period are evaluated according to their ability to reflect successfully the emotions and meaning of the text set in musical terms. The same period also witnessed the rise of the five- and six-voice chanson, whose most important exponents are Josquin des Prez, Pierre de La Rue, and Jean Mouton. The new expanded textures posed several compositional challenges but also offered greater opportunities for text expression. Rhetorical analysis is particularly suitable for this repertory as it is justified by the composers’ contacts with humanistic ideals and the newer text-expressive approach. Especially Josquin’s exposure to humanism must have been extensive during his long-lasting residence in Italy, before returning to Northern France, where he most likely composed his multi- voice chansons. -

2010 Program

Sixteenth Century Society & Conference Montréal 2010 2009-2010 OFFICERS President: Jeffrey R. Watt Vice-President: Cathy Yandell Past-President: Amy Nelson Burnett Executive Director: Donald J. Harreld Financial Officer: Eric Nelson ACLS Representative: Allyson M. Poska Endowment Chairso: Raymond Mentzer & Ronald Fritze COUNCIL Class of 2010: Walter S. Melion, Jeannine Olson, Allyson Poska, Randall Zachmann Class of 2011: Peter Marshall, Elisabeth Wåghäll Nivre, Katherine McIver, Michael Walton Class of 2012: Kathryn Edwards,o Emidio Campi, Sheila ffolliott, Allison Weber PROGRAM COMMITTEE Chair: Cathy Yandell History: Sigrun Haude English Literature: Scott Lucas German Studies: Bethany Wiggin Italian Literature: Meredith Ray Theology: R. Ward Holder History of Science: Bruce Janacek French Literature: Jean-Claude Carron Spanish and Latin American Studies: Elizabeth Lehfeldt Art History:o Cynthia Stollhans NOMINATING COMMITTEE Emmet McLaughlin (Chair), Torrance Kirby, Mary B. McKinley, Bruceo Gordon, Pia Cuneo 2009–2010 SCSC PRIZE COMMITTEES Gerald Strauss Book Prize Ronald K. Rittgers, Amy Leonard, Timothy Fehler Bainton Art History Book Prize Lynette Bosch, James Clifton, Naomi Yavneh Bainton History/Theology Book Prize Christopher Ocker, Andrew Spicer, Kathryn Edwards Bainton Literature Book Prize Christopher Baker, Julia Griffin, Cynthia Skenazi Bainton Reference Book Prize John Farthing, Ronald Fritze, Konrad Eisenbichler Grimm Prize Roy Vice, Charles Parker, Peter Wallace Roelker Prize Megan Armstrong, Karen Spierling, Jeffrey R. -

Discover Something About Mary, Queen of Scots CONTENTS Betrothal to England

DISCOVER QUEEN OF SCOTS Born into Conflict ........................................................ 4 Infant Queen ................................................................. 5 Discover Something about Mary, Queen of Scots CONTENTS Betrothal to England ................................................. 6 Coronation ..................................................................... 7 To describe the short life of Mary, Queen of Scots as ‘dramatic’ is an understatement. The Rough Wooing .................................................... 8 Auld Alliance Renewed ............................................. 9 By the age of 16 she was Queen of Scotland and France (and, many believed, rightfully of England and Smuggled to France ................................................ 10 Ireland, too); as an infant she had been carried to castles around Scotland for her safety; by the time she Acknowledgments Precocious Beauty ..................................................... 11 turned 18 she had been married and widowed; as a young woman she was striking, tall and vivacious; This free guide has been funded by the following organisations: Teenage Marriage ..................................................... 12 she spoke five languages; she could embroider and ride with equal adroitness; she upheld her Catholic Queen over the Water? .......................................... 13 faith against the Protestant reformer, John Knox; she led her troops to put down two rebellions; she Historic Scotland Queen Consort of France .....................................