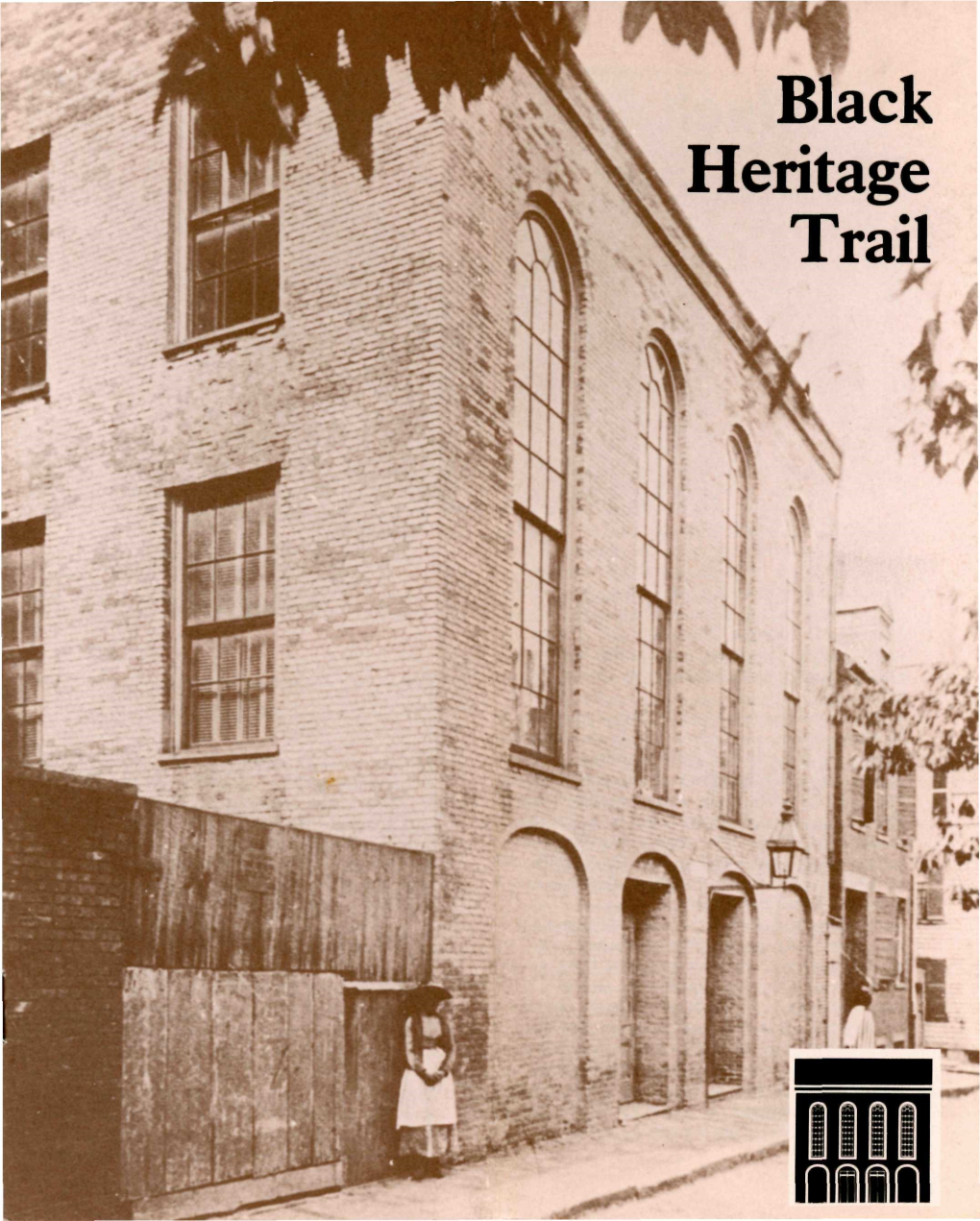

Black Heritage Trail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution

Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Collection of Essays Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Collection of Essays Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Kentucky Heritage Council © Essays compiled by Alicestyne Turley, Director Underground Railroad Research Institute University of Louisville, Department of Pan African Studies for the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission, Frankfort, KY February 2010 Series Sponsors: Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Kentucky Historical Society Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Kentucky Heritage Council Underground Railroad Research Institute Kentucky State Parks Centre College Georgetown College Lincoln Memorial University University of Louisville Department of Pan African Studies Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission The Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission (KALBC) was established by executive order in 2004 to organize and coordinate the state's commemorative activities in celebration of the 200th anniversary of the birth of President Abraham Lincoln. Its mission is to ensure that Lincoln's Kentucky story is an essential part of the national celebration, emphasizing Kentucky's contribution to his thoughts and ideals. The Commission also serves as coordinator of statewide efforts to convey Lincoln's Kentucky story and his legacy of freedom, democracy, and equal opportunity for all. Kentucky African American Heritage Commission [Enabling legislation KRS. 171.800] It is the mission of the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission to identify and promote awareness of significant African American history and influence upon the history and culture of Kentucky and to support and encourage the preservation of Kentucky African American heritage and historic sites. -

LEWIS HAYDEN and the UNDERGROUND RAILROAD

1 LEWIS HAYDEN and the UNDERGROUND RAILROAD ewis Hayden died in Boston on Sunday morning April 7, 1889. L His passing was front- page news in the New York Times as well as in the Boston Globe, Boston Herald and Boston Evening Transcript. Leading nineteenth century reformers attended the funeral including Frederick Douglass, and women’s rights champion Lucy Stone. The Governor of Massachusetts, Mayor of Boston, and Secretary of the Commonwealth felt it important to participate. Hayden’s was a life of real signi cance — but few people know of him today. A historical marker at his Beacon Hill home tells part of the story: “A Meeting Place of Abolitionists and a Station on the Underground Railroad.” Hayden is often described as a “man of action.” An escaped slave, he stood at the center of a struggle for dignity and equal rights in nine- Celebrate teenth century Boston. His story remains an inspiration to those who Black Historytake the time to learn about Month it. Please join the Town of Framingham for a special exhibtion and visit the Framingham Public Library for events as well as displays of books and resources celebrating the history and accomplishments of African Americans. LEWIS HAYDEN and the UNDERGROUND RAILROAD Presented by the Commonwealth Museum A Division of William Francis Galvin, Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Opens Friday February 10 Nevins Hall, Framingham Town Hall Guided Tour by Commonwealth Museum Director and Curator Stephen Kenney Tuesday February 21, 12:00 pm This traveling exhibit, on loan from the Commonwealth Museum will be on display through the month of February. -

Black Abolitionists Used the Terms “African,” “Colored,” Commanding Officer Benjamin F

$2 SUGGESTED DONATION The initiative of black presented to the provincial legislature by enslaved WHAT’S IN A NAME? Black people transformed a war men across greater Boston. Finally, in the early 1780s, Elizabeth “Mumbet” Freeman (Image 1) to restore the Union into of Sheffield and Quock Walker of Framingham Throughout American history, people Abolitionists a movement for liberty prevailed in court. Although a handful of people of African descent have demanded and citizenship for all. of color in the Bay State still remained in bondage, the right to define their racial identity (1700s–1800s) slavery was on its way to extinction. Massachusetts through terms that reflect their In May 1861, three enslaved black men sought reported no slaves in the first census in 1790. proud and complex history. African refuge at Union-controlled Fort Monroe, Virginia. Americans across greater Boston Rather than return the fugitives to the enemy, Throughout the early Republic, black abolitionists used the terms “African,” “colored,” Commanding Officer Benjamin F. Butler claimed pushed the limits of white antislavery activists and “negro” to define themselves the men as “contrabands of war” and put them to who advocated the colonization of people of color. before emancipation, while African work as scouts and laborers. Soon hundreds of In 1816, a group of whites organized the American Americans in the early 1900s used black men, women, and children were streaming Colonization Society (ACS) for the purpose of into the Union stronghold. Congress authorized emancipating slaves and resettling freedmen and the terms “black,” “colored,” “negro,” the confiscation of Confederate property, freedwomen in a white-run colony in West Africa. -

Wendell Phillips Wendell Phillips

“THE CHINAMAN WORKS CHEAP BECAUSE HE IS A BARBARIAN AND SEEKS GRATIFICATION OF ONLY THE LOWEST, THE MOST INEVITABLE WANTS.”1 For the white abolitionists, this was a class struggle rather than a race struggle. It would be quite mistaken for us to infer, now that the civil war is over and the political landscape has 1. Here is what was said of the Phillips family in Nathaniel Morton’s NEW ENGLAND’S MEMORIAL (and this was while that illustrious family was still FOB!): HDT WHAT? INDEX WENDELL PHILLIPS WENDELL PHILLIPS shifted, that the stereotypical antebellum white abolitionist in general had any great love for the welfare of black Americans. White abolitionist leaders knew very well what was the source of their support, in class conflict, and hence Wendell Phillips warned of the political danger from a successful alliance between the “slaveocracy” of the South and the Cotton Whigs of the North, an alliance which he termed “the Lords of the Lash and the Lords of the Loom.” The statement used as the title for this file, above, was attributed to Phillips by the news cartoonist and reformer Thomas Nast, in a cartoon of Columbia facing off a mob of “pure white” Americans armed with pistols, rocks, and sticks, on behalf of an immigrant with a pigtail, that was published in Harper’s Weekly on February 18, 1871. There is no reason to suppose that the cartoonist Nast was failing here to reflect accurately the attitudes of this Boston Brahman — as we are well aware how intensely uncomfortable this man was around any person of color. -

Early Newspaper Accounts of Prince Hall Freemasonry

Early Newspaper Accounts of Prince Hall Freemasonry S. Brent Morris, 33°, g\c\, & Paul Rich, 32° Fellow & Mackey Scholar Fellow OPEN TERRITORY n 1871, an exasperated Lewis Hayden1 wrote to J. G. Findel2 about the uncertain and complicated origins of grand lodges in the United States and the inconsistent attitudes displayed towards the char- I tering in Boston of African Lodge No. 459 by the Grand Lodge of Eng- land: “The territory was open territory. The idea of exclusive State jurisdiction by Grand Lodges had not then been as much as dreamed of.” 3 The general 1. Hayden was a former slave who was elected to the Massachusetts legislature and raised money to finance John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry. His early life is described by Harriet Beecher Stowe in her book, The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (Jewett, Proctor & Worthington, 1853). 2. Findel was a member of Lodge Eleusis zur Verschwiegenheit at Baireuth in 1856 and edi- tor of the Bauhütte as well as a founder of the Verein Deutscher Freimaurer (Union of Ger- man Freemasons) and author in 1874 of Geist unit Form der Freimaurerei (Genius and Form of Freemasonry). 3. Lewis Hayden, Masonry Among Colored Men in Massachusetts (Boston: Lewis Hayden, 1871), 41. Volume 22, 2014 1 S. Brent Morris & Paul Rich theme of Hayden’s correspondence with Findel was that African-American lodges certainly had at least as much—and possibly more—claim to legiti- mate Masonic origins as the white lodges did, and they had been denied rec- ognition because of racism.4 The origins of African-American Freemasonry in the United States have generated a large literature and much dispute. -

William Cooper Nell. the Colored Patriots of the American Revolution

William Cooper Nell. The Colored Patriots of the American ... http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/nell/nell.html About | Collections | Authors | Titles | Subjects | Geographic | K-12 | Facebook | Buy DocSouth Books The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution, With Sketches of Several Distinguished Colored Persons: To Which Is Added a Brief Survey of the Condition And Prospects of Colored Americans: Electronic Edition. Nell, William Cooper Funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities supported the electronic publication of this title. Text scanned (OCR) by Fiona Mills and Sarah Reuning Images scanned by Fiona Mills and Sarah Reuning Text encoded by Carlene Hempel and Natalia Smith First edition, 1999 ca. 800K Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1999. © This work is the property of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It may be used freely by individuals for research, teaching and personal use as long as this statement of availability is included in the text. Call number E 269 N3 N4 (Winston-Salem State University) The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH digitization project, Documenting the American South. All footnotes are moved to the end of paragraphs in which the reference occurs. Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line. All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as entity references. All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and " respectively. All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively. -

The Easton Family of Southeast Massachusetts: the Dynamics Surrounding Five Generations of Human Rights Activism 1753--1935

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2006 The Easton family of southeast Massachusetts: The dynamics surrounding five generations of human rights activism 1753--1935 George R. Price The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Price, George R., "The Easton family of southeast Massachusetts: The dynamics surrounding five generations of human rights activism 1753--1935" (2006). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 9598. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/9598 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission ___________ Author's Signature: Date: 7 — 2 ~ (p ~ O b Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -

African-Americans in the Revolution

African-Americans in the Revolution OBJECTIVES The student will be able to: In “The Negro in the American Revolution,” Benjamin Quarles 1) list the responsibilities said the African-American was “a participant and a symbol. He was of African-American soldiers active on the battlefronts and behind the lines . The Negro’s role in the Revolution, and; in the Revolution can best be understood by realizing that his major loyalty was not to a place nor to a people, but to a principle. Insofar 2) discuss the contributions as he had freedom of choice, he was likely to join the side that made of at least three African- him the quickest and best offer in terms of those ‘unalienable rights’ Americans of the era. of which Mr. Jefferson had spoken.” 3) identify duties African-Americans served in the Massachusetts companies and in most often performed by the state militias of northern states. The Rhode Island regiment at African-Americans. Yorktown was three-fourths black. African-Americans also served in the navy. It is estimated that about 5,000 African-Americans served in the war. Many African-Americans fought with the British since the British commander, Sir Henry Clinton, offered freedom to slaves who would fight for the King. The British used the runaway slaves as guides, spies and laborers (carpenters, blacksmiths, etc.). By using the African-Americans as laborers, whites were free to be soldiers. Many slaves left when the British evacuated after the end of the war. Quarles says. “Thousands of Negroes were taken to other islands in the British West Indies . -

The Role of Blacks in the Revolutionary War

Title of Unit: The Forgotten Patriots: The Role of Blacks in the Revolutionary War Vital theme of the unit: Students will learn how African Americans were important in the war effort. Author and contact information: Tammie McCarroll-Burroughs Lenoir City Elementary School 203 Kelley Lane Lenoir City, Tennessee 37771 Phone: (865) 986-2009 ex. # 7349 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Grade Level: Intermediate – Fourth or Fifth Grade Curriculum Standards Addressed: 4.5.6; 4.5.7; 4.5.8; 4.5.11; 4.6.2; 4.6.3 Technology Used: Primary Source Materials Provided in Lessons: Discharge Papers of Oliver Cromwell Newspaper Article from Burlington Gazette Affidavit of Service and Need of Pension Affidavits of Martin Black’s Service and Need of Pension Transcript of Craven County Court Minutes – Included in Background Information Pension Record Approval Page Listing Amount of Pension Additional Sources for Teachers in Separate Folder: Peter Salem Documents and Excerpt from Patriots of Color Phylllis Wheatley Selected Poems and Letter from George Washington Related Web Sites for More Information Unit introduction and overview of instructional plan: Over the course of this unit, students will gain understanding of the roles of freed and enslaved African American Patriots through lessons that go beyond the lessons taught in the textbook. The lessons are based on events and issues that may not necessarily be covered in the textbook. The two selected soldiers and their Pension Records are not identified in our textbook. Peter Salem is identified by name in one lesson of the Fourth Grade text Early United States (Harcourt Brace). -

What Was the Heigh-Ho Club?

WHAT WAS THE HEIGH-HO CLUB? The above picture and a letter vaguely that the club was encouraged were sent to us by a woman from or started by the Unitarian minister Orleans, Massachusetts. There are (Hobbs?) but it was never ten signatures on the back of the religiously affiliated. It seems to picture: have been purely social, sponsoring plays, outings, dances, etc. James H. Critchett We have unfortunately failed to Everett H. Critchett find any reference at the Watertown Harry F. Gould Public Library to this club, Waldo Stone Green however, several of these names were Francis Hathaway Kendall found to be associated with the Benjamin Fay McGlauflin Theodore Parker Fraternity cf the Alfred Foster Jewett First Parish Unitarian Church. Royal David Evans If you or a friend or relative LaForest Harris Howe have any pertinent information on William Henry Benjamin Jr the Heigh-Ho Club or any of its members, please send it to us. This The letter states that sometime is an interesting sidelight on life after 1905, a group of college-age in Watertown in the early 1900's and young men from Watertown formed "The we would like to explore it further. Heigh-Ho Club". She remembers WATERTOWN - HOW IT GREW! On November 16, 1994 a joint and establishing trade and commerce, meeting between the Friends of the for Watertown stood at the crossing Library and the Historical Society place on the Charles River for the of Watertown was conducted in the stagecoach route on the road west. Pratt room of the Free Public Freight was unloaded here for Library. -

Race, Party, and African American Politics, in Boston, Massachusetts, 1864-1903

Not as Supplicants, but as Citizens: Race, Party, and African American Politics, in Boston, Massachusetts, 1864-1903 by Millington William Bergeson-Lockwood A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Martha S. Jones, Chair Professor Kevin K. Gaines Professor William J. Novak Professor Emeritus J. Mills Thornton III Associate Professor Matthew J. Countryman Copyright Millington William Bergeson-Lockwood 2011 Acknowledgements Writing a dissertation is sometimes a frustratingly solitary experience, and this dissertation would never have been completed without the assistance and support of many mentors, colleagues, and friends. Central to this project has been the support, encouragement, and critical review by my dissertation committee. This project is all the more rich because of their encouragement and feedback; any errors are entirely my own. J. Mills Thornton was one of the first professors I worked with when I began graduate school and he continues to make important contributions to my intellectual growth. His expertise in political history and his critical eye for detail have challenged me to be a better writer and historian. Kevin Gaines‘s support and encouragement during this project, coupled with his insights about African American politics, have been of great benefit. His push for me to think critically about the goals and outcomes of black political activism continues to shape my thinking. Matthew Countryman‘s work on African American politics in northern cities was an inspiration for this project and provided me with a significant lens through which to reexamine nineteenth-century black life and politics. -

Embodied Resistance, Geopolitics, and a Black Sense of Freedom Vanessa Lynn Lovelace University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 5-3-2017 Trailing Freedom: Embodied Resistance, Geopolitics, and a Black Sense of Freedom Vanessa Lynn Lovelace University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Lovelace, Vanessa Lynn, "Trailing Freedom: Embodied Resistance, Geopolitics, and a Black Sense of Freedom" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 1456. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1456 Trailing Freedom: Embodied Resistance, Geopolitics, and a Black Sense of Freedom Vanessa Lynn Lovelace, PhD University of Connecticut, [2017] This project challenges the conventional construction of the academic and real-life search for freedom by exploring how Blackness changes the dynamics of who is a liberated and free subject. In order to do so, this project engages with three specific iterations of freedom: freedom as liberty, freedom as emancipation and freedom as revolution. By focusing on “Freedom Trails”- namely, the Boston Freedom Trail, the geography of the Nat Turner slave rebellion, and the embodied geography of Black Power – this project maps the spaces that enhance a Black sense of freedom. These particular cases conceive of freedom in both conventional and revolutionary ways. Conventional freedom gets marked in the terrain, while Black Revolutionary Freedom is covered and silenced. This project grapples with what it is people who inherit and own Blackness have to do in order to be free? I employ an assemblage of methodologies, which creates an expanded archive through memory work, haunting, deconstruction and textual interdiction. This project is just as much about trailing freedom as it is about the method of Freedom Trails.