Shaping the Deep Memories of Russians and Ukrainians

Total Page:16

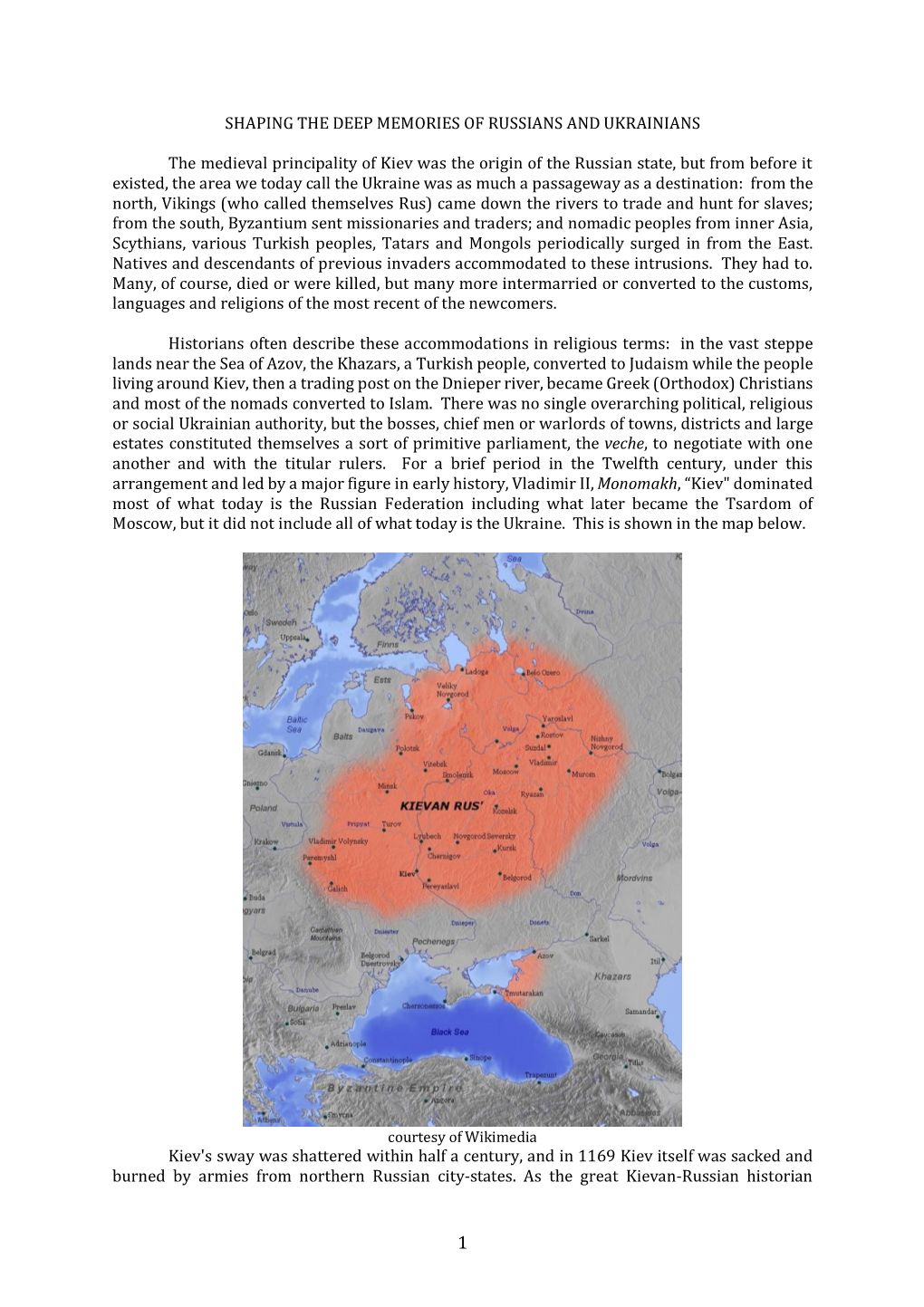

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ukrainian Qrestion in Its National Aspect Nownnadv

Memorandum ol"l The Ukrainian Qrestion in its National Aspect NOWnnADv THE TTKRAINE A Rcprint of a Lecture delivered on Uhrainian Ilistorv and Present Day Political Problems. By BnnwrN S-qNns. Paper, Imperial 8vo. Price 2/- nei. Loxnorq: Fnencrs Gnrpprtns MEMORANDUM ON THE UkrainianQ.rtion in its National Aspecr Compiledon behalfof the " Cercledes Ukrainiens,"Paris, and the " Ukraine.Committee,"London BY YAROSLAVFEDORTCHOUK LONDON FRANCIS GRIFFITHS 34 I'IAIDEN LANE, STRAND, W.C. rgr4. t l^ F r.""I Translator's Foreword T uts Pamphlet,which is issuedsimultan'eously in the Englishand French languages,contains two distinctparts. They rvereboth written bv M. YaroslavFedortchouk, who is the Secretaryof the Cercle des Uhrainiensd Paris,the -|.: author of Lc Riveil ,.i l national desUhrainiens (Paris, lgl2l, an important brochureon the question,and a refular contribrtor to the 0ourrier Eurap{en on Ukrainian questions. The first part is a list of desideratarvhich was read on Monday, February16th, 1913, at the Conferenceorganised by the " Nationalitiesand SubjectRaces Comrnittee,,' and comprises what M. Fedortchouk considersto be the minimum of the claimsurged by the Ukrainianeducated classes. The secondis an explanatorymemorandum, which is now beingpublished, so as to give in a cheapand simple form the wholeof the Ukrainequestion in moderntimes For thosewho wish to study the questionfrom an histori cal point of view, there is a volume publishedat the be- ginning of l9l4 by Mr. Francis Griffiths, 34, Maiden Lane, Strand, London, England. It is entitled The ["]brain.e,and has an extensivebibliography. It is fully illustrated,and is sold at the price of 2s net. During February,1914, about the time that M. -

University of Edinburgh Postgraduate Journal of Culture and the Arts Issue 17 | Autumn 2013

University of Edinburgh Postgraduate Journal of Culture and the Arts Issue 17 | Autumn 2013 www.forumjournal.org Title Enthronement Rituals of the Princes of Rus’ (twelfth-thirteenth centuries) Author Alexandra Vukovich Publication FORUM: University of Edinburgh Postgraduate Journal of Culture and the Arts Issue Number 17 Issue Date Autumn 2013 Publication Date 06/12/2013 Editors Victoria Anker & Laura Chapot FORUM claims non-exclusive rights to reproduce this article electronically (in full or in part) and to publish this work in any such media current or later developed. The author retains all rights, including the right to be identified as the author wherever and whenever this article is published, and the right to use all or part of the article and abstracts, with or without revision or modification in compilations or other publications. Any latter publication shall recognise FORUM as the original publisher. FORUM | ISSUE 17 Vukovich 1 Enthronement Rituals of the Princes of Rus’ (twelfth- thirteenth centuries) Alexandra Vukovich The University of Cambridge This article examines the translation, transformation, and innovation of ceremonies of inauguration from the principality of Kiev to the principality of Vladimir-Suzdal’ and the city of Novgorod in the early Russian period (twelfth-thirteenth centuries). The ritual embellishment of inauguration ceremonies suggests a renewed contact between early Rus’ and Byzantium. Medieval historians have long understood the importance of rituals in communicating the sacredness of ruling offices. Ceremonies of enthronement, anointings of rulers by bishops, and the entry of a ruler into a city or a monastic complex were all meant to edify, promote, and render visible the authority of the ruler and that of the Church. -

Soviets in Central Asia

Soviets in Central Asia By W.P & Zelda K. Coates Originally printed in London in 1951 Reprinted in New York in 2017 Red Star Publishers www.RedStarPublishers.org Mechanisation invades the cotton-fields of Soviet Asia. A tractor at work sowing cotton at the “Bolshevik” Collective Farm, Tadzhikistan. The driver, Brigade-Leader D. Artykov. ii FOREWORD This book is the outcome of an extremely Interesting journey made by the authors recently in the Central Asian Republics of the U.S.S.R. The first part deals with the ancient history of the peoples of Central Asia, the conquest of these lands by the Tsarist Government and their liberation in November 1917. The second part gives a description of life in the Soviet Central Asian Republics and shows what the Soviet national policy has ac- complished. In view of the awakening of the peoples of the East, particularly in Asia, and indeed of all colonial peoples, the question of how to deal with these more backward nationalities is of the utmost impor- tance not only to the colonial peoples themselves, but also to us Europeans, Whatever may be thought of the Soviet system, whether one likes or dislikes it, no one can deny that the Soviet national pol- icy—a policy well thought out by Lenin and Stalin and their col- leagues long before the revolution—has been an outstanding suc- cess. The U.S.S.R. has made an important contribution to the study, theory and practice of this important question. The lessons to be derived from the Soviet experience may be of invaluable help to the rest of the world in dealing with national minorities, and it is the hope of the authors that this book will be of some service in spread- ing information of what has been done in the Central Asian Soviet Socialist Republics and in pointing to the lessons to be learnt there- from. -

27 Siarhei Pivavarchyk BELARUSIAN PANYAMONNE in the EARLY

Doctor of Historical Sciences, Associate Professor, Yanka Kupala State University of Grodno, Faculty of History, Communication and Tourism Head of the Department of History of Belarus, Archeology and Special Historical Disciplines phone: +375 29 78 03 475 Siarhei Pivavarchyk BELARUSIAN PANYAMONNE IN THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES (10TH–13TH CENTURIES) БЕЛОРУССКОЕ ПОНЕМАНЬЕ В РАННЕМ СРЕДНЕВЕКОВЬЕ (X–XIII ВВ.) Summary. The article examines the political, ethnic and economic history of the Belarusian Panyamonne in the early Middle Ages (10th – 13th centuries). The Belorussian Panyamonne is a historical and ethnographic region of modern Belarus, located in the Neman river basin. The analysis of written and archaeological sources shows that the population of the region was poli-ethnic during this period. The East Slavic (Dregoviches, Volhynians, Krivichs) and the West Slavic (Mazovians) tribes came into contact with the Baltic tribes (Yotvingians, Lithuanians, Prussians). The cities of the Belarusian Panyamonne (Grodno, Slonim, Volkovysk, Novogrudok, Tureisk) were founded by the Slavs in the 11th – 13th centuries and quickly became centers of political, economic, and cultural life in the region. The unique architectural school was formed in 12th century in Grodno. In the middle of the 13th century the territory of the Belarusian Panyamonne became the center of the formation new political association - the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Key words: Belarusian Panyamonne, written sources, Ipatiev Chronicle, archaeological excavations, political history, socio-economic development, Slavic tribes, Yotvingians, Galician-Volhynian princes, fortifed city. Belarusian Panyamonne is a historical and ethnographic region of Belarus. It is distinguished by a complex of specifc ethno-cultural features and occupies the territory of Grodno and adjacent parts of Brest and Minsk regions. -

HARVARD UKRAINIAN STUDIES Volume X Number 3/4 December 1986

HARVARD UKRAINIAN STUDIES Volume X Number 3/4 December 1986 Concepts of Nationhood in Early Modern Eastern Europe Edited by IVO BANAC and FRANK E. SYSYN with the assistance of Uliana M. Pasicznyk Ukrainian Research Institute Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts Publication of this issue has been subsidized by the J. Kurdydyk Trust of the Ukrainian Studies Fund, Inc. and the American Council of Learned Societies The editors assume no responsibility for statements of fact or opinion made by contributors. Copyright 1987, by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved ISSN 0363-5570 Published by the Ukrainian Research Institute of Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A. Typography by the Computer Based Laboratory, Harvard University, and Chiron, Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts. Printed by Cushing-Malloy Lithographers, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Articles appearing in this journal are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. CONTENTS Preface vii Introduction, by Ivo Banac and Frank E. Sysyn 271 Kiev and All of Rus': The Fate of a Sacral Idea 279 OMELJAN PRITSAK The National Idea in Lithuania from the 16th to the First Half of the 19th Century: The Problem of Cultural-Linguistic Differentiation 301 JERZY OCHMAŃSKI Polish National Consciousness in the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century 316 JANUSZ TAZBIR Orthodox Slavic Heritage and National Consciousness: Aspects of the East Slavic and South Slavic National Revivals 336 HARVEY GOLDBLATT The Formation of a National Consciousness in Early Modern Russia 355 PAUL BUSHKOVITCH The National Consciousness of Ukrainian Nobles and Cossacks from the End of the Sixteenth to the Mid-Seventeenth Century 377 TERESA CHYNCZEWSKA-HENNEL Concepts of Nationhood in Ukrainian History Writing, 1620 -1690 393 FRANK E. -

A HISTORY of RUSSIA All Risplits Resejt'ed

HANDBOUND AT THE UNlVtRSITY OF Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/historyofrussia01kliu :iS^7 1 A HISTORY OF RUSSIA All risplits reseJT'ed. 1 ^ :^ A // HISTORY ^/RUSSIA BY V. O. KLUCHEVSKY LATE PROFESSOR OF RUSSIAN HISTORY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF MOSCOW TRANSLATED BY C. J. HOGARTH ^^^'^' X K\/pc, pycCKOM iicrQ^i^m(j:u>aKuiii<^oi VOLUME ONE LONDON: J. M. DENT ^ SONS, LTD. NEW YORK: E. P. BUTTON ^ CO. 191 DK Ho Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson &• Co. At the Ballantyne Press, Edinburgh — -V CONTENTS CHAPTER I PAGE The two points of view in the study of history— The principal factor in the development of Russian social life —The iour principal periods of Russian history —The Ancient Chronicle ; its genesis, authorship, and contents . I CHAPTER n Historical value of the Ancient Chronicle— Its importance for later Russian historians—A chronological error—The origin of that error—The work of compiling the Chronicle—Defects in the older versions—The theory of Slavonic unity—Manuscripts of the twelfth century—The divergent points of view of their authors 19 CHAPTER III Principal factors of the first period of Russian history —The two theories as toils starling-point—The races who inhabited Southern Russia before the coming of the Eastern Slavs—The Ancient Chronicle's tradition concerning the dispersal of the Slavs from the Danube—Jornandes on their distribution during the sixth century—The military union of the Eastern Slavs in the Carpathians—The period and peculiar features of their settlement of the Russian plain— Results of that settlement ...... -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1941

TIE отіниш English supplement of SVOBODA, Ukrainian daily, founded 1893. Dedicated to the needs and interests of young Americans of Ukrainian descent 'No. 4 JERSEY CITY, N. J., FRIDAY, JANUARY 24, 1941 VOL. IX ТИЕ UKRAINIAN NATIONAL IflttON ACT AN ANNOUNCEMENT Of JANUARY 22, 1919 I Twenty two years ago last Wed- What eventually nullified this Lectures on Ukraine at Columbia University K nesday, on January 22, 1919 re- singular achievement were the The Department of East European Languages of Co !••. presentatives' of Eastern (Greater) overpowering adds arrayed against lumbia University, in -conjunction with the Ukrainian Na- and Western Ukraine met in the the young Ukrainian National Re- і historic St. Sophia Square in Kiev . public. From all sides Ukraine's tional Association, announces a series of lectures on Uk | • and there amidst great rejoicing rainian history, culture, and literature commencing on r proclaimed the union of these two ancient and predatory enemies con I components parts of Ukraine into verged upon her: from the north February 1І,.Д941.. one, indivisible, and independent the Bolsheviki hordes with their Unless otherwise indicated, the lectures will be held in і and democratic Ukrainian National reign or .terror; from the south and Room 305, Schermerhorn Hall, ^telumbia University, at 8 P. Republic. east the royalist or "White" Rus M. Fridays eyeriings. Admission will be free and all who Today these territories are again sian forces under Denikin and I united, but not within the Ukrain- later -Wrangel; from the .west, the are interested are welcome. I ian National Republic. For before Polish armies; and from the south Professor Clarence A. -

Fall 2009 Issue

Notes from the Editor Welcome to another issue of Diplomacy World, which Design contest. This is a contest which was inspired by has now served as the flagship publication of the one which ran decades ago in Diplomacy World. Diplomacy hobby for over 35 years. The hobby has Despite the somewhat lackluster response some of prior seen a great deal of change over that long period, and contests have received, I’ve got my fingers crossed that Diplomacy World will continue our efforts to adjust to the longer timeline (and attractive prizes) will bring out those changes, and when possible to be at the forefront. some new and original variant designs. If not…well, add it to the list of failures in my life. Long list, folks…L-O-N- One of those efforts is the welcome addition of Chris G list. Babcock as Technology Editor. With the advances in social networking and on-line gaming, the opportunities Elsewhere in this issue you’ll find a news blurb about a to see real breakthroughs in the way Diplomacy games remarkable sponsorship deal the Australian and New are available worldwide are countless. Chris has been Zealand Diplomacy hobby has worked to acquire. I had at the forefront of some of those projects, and his hoped to get a full article on how they accomplished the knowledge both of the possibilities and the pitfalls will achievement, but for this issue at least you will have to certainly make his articles, and those he solicits from be satisfied with the announcement itself. others, exceptional reading. -

Princess Olga: Eastern Woman Through Western Eyes

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2020 Princess Olga: Eastern Woman Through Western Eyes Lee A. Hitt Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Recommended Citation Hitt, Lee A., "Princess Olga: Eastern Woman Through Western Eyes" (2020). University Honors Program Theses. 541. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/541 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Princess Olga Eastern Woman Through Western Eyes An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in History. By Lee A. Hitt Under the mentorship of Dr. Olavi Arens ABSTRACT In the Viking world, stories of women inciting revenge reach back through the past into oral history. These legends were written down in the sagas of the Icelanders. Princess Olga’s story was recorded in the Russian Primary Chronicle. Though her heritage is uncertain, Olga ruled in Kievan Rus’ in the ninth and tenth centuries. Kievan Rus’ was governed by Vikings from Sweden known as Varangians. There are similarities between Olga’s story and the sagas. This study applies the research of scholars who pioneered the topic of gendering the Old Norse Icelandic literature, to compare her story to the gender norms and cultural values of the Scandinavians. The goal is to tie Olga’s heritage, to the greater Viking world. -

Feasibility Study on Recovery and Utilization of Coal Mine Gas (CMG) at Donetsk Coal Field

NEDO—1C—00ER03 Feasibility Study on Recovery and Utilization of Coal Mine Gas (CMG) at Donetsk Coal Field March, 2001 New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization Cntrusted to : Japan Coal Energy Center Feasibility Study on Recovery and Utilization of Coal Mine Gas (CMG) at Donetsk Coal Field Entrusted to: Japan Coal Energy Center Date of Preparation of the Report: March 2001 (242 pages) This study has been carried out with a view to the execution of a feasibility study for the Coal Mine Gas Recovery and Utilization Project in the Ukraine and the establishment of a Joint Implementation Project among Leading Industrialized Countries under the Kyoto Mechanism. NEDO—1C—00ER03 Feasibility Study on Recovery and Utilization of Coal Mine Gas (CMG) at Donetsk Coal Field March, 2001 New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization Entrusted to : Japan Coal Energy Center Foreword This Report presents the findings of Feasibility Study on Recovery and Utilization of Coal Mine Gas (CMG) at Donetsk Coal Field carried out in fiscal 2000 by the Japan Coal Energy Center (JCOAL) under an assignment from the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO). The 3rd Session of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COPS) was held in Kyoto in December 1997. At the Conference, the Kyoto Protocol was adopted. For the prevention of global warming due to the emission of greenhouse gases, including primarily carbon dioxide, the industrialized nations agreed to reduce their average emission level by at least 5% during the period from 2008 to 2012 as compared with the 1990 level. -

Kiev Or Kyiv[A] (Ukrainian: Київ, Romanized: Kyiv; Russian: Киев, Romanized: Kiyev) Is the Capital and Most Populous City of Ukraine

Kiev or Kyiv[a] (Ukrainian: Київ, romanized: Kyiv; Russian: Киев, romanized: Kiyev) is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. Its population in July 2015 was 2,887,974[1] (though higher estimated numbers have been cited in the press),[12] making Kiev the 6th-most populous city in Europe.[13] Kiev is an important industrial, scientific, educational and cultural center of Eastern Europe. It is home to many high-tech industries, higher education institutions, and historical landmarks. The city has an extensive system of public transport and infrastructure, including the Kiev Metro. The city's name is said to derive from the name of Kyi, one of its four legendary founders. During its history, Kiev, one of the oldest cities in Eastern Europe, passed through several stages of prominence and obscurity. The city probably existed as a commercial center as early as the 5th century. A Slavic settlement on the great trade route between Scandinavia and Constantinople, Kiev was a tributary of the Khazars,[14] until its capture by the Varangians (Vikings) in the mid-9th century. Under Varangian rule, the city became a capital of the Kievan Rus', the first East Slavic state. Completely destroyed during the Mongol invasions in 1240, the city lost most of its influence for the centuries to come. It was a provincial capital of marginal importance in the outskirts of the territories controlled by its powerful neighbours, first Lithuania, then Poland and Russia.[15] The city prospered again during the Russian Empire's Industrial Revolution in the late 19th century. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1941

THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY English supplement' of SVOBODA. Ukrainian daily, founded 1893. Dedicated to the needs and interests of young Americans of Ukrainian descent No. 5 JERSEY CITY, N. J., FRIDAY, JANUARY 31, 1941 VOL. IX NEW YORK LIBRARY WANTS BlDDLr> l·OtXD UKRAINIANS LETTERS FROM OLD COUNTRY Yl·.K\ HOSPITABLE THE LECTURES ON UKRAINE AT COLUMBIA The hospitable qualities of the Realising that commonplaces of Ukrainiai, · . highly praised by today may be of great importance Mrs. Fra ; Kiddle, wife of the for the next generation of students As announced last week, a series of approximately American \ issador to Poland, and scholars, the*New York Public in recounttii- their experiences in Library is collecting letters written eight lectures on Ukraine will be given at Columbia Univer that coun; a Weekly represen today by people who have seen at sity on Friday evenings, beginning February 14. They will tative prio! i«t her lecture on that first hand some oj the events that be sponsored by the Department of East European Lan subject at¡d fifth column activi have unrolled under our eyes in ties at Col і University, Thurs Europe during the past few years. guages of Columbia University, in conjunction with the Uk day eveniii_ ! inuary 23, under the It makes an earnest plea for de rainian National Association. Professor Clarence A. Man auspices ' he Department of livery to it of letters, manuscripts, ning, Acting Executive Officer of the Department, will pre East Euro] l¿anguages. and papers of this class. It as '"Yes, w knew the Ukrainians sures, donors that such material side and introduce the speakers.